Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

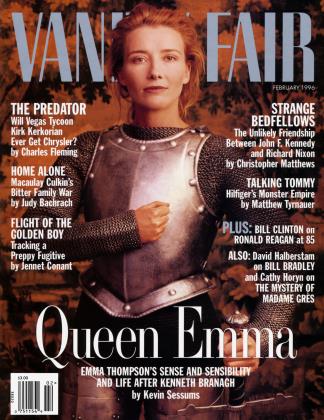

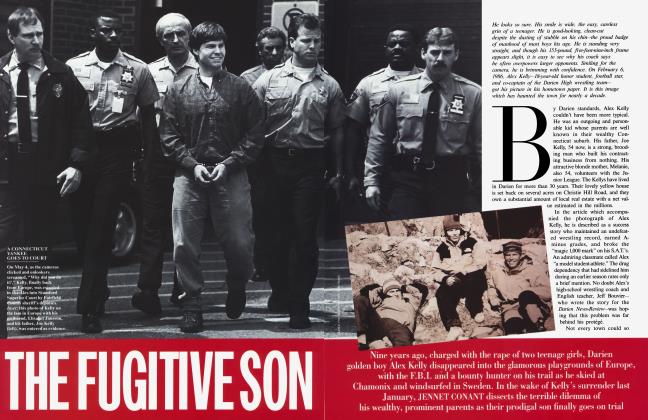

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowTHE PREDATOR

In Hollywood as on Wall Street, Las Vegas billionaire Kirk Kerkorian is controversial and mysterious. Did he destroy MGM/UA or save it? How did he lose control of his casino investments with a single phone call from a mobster? And why is he now moving heaven and earth to gain control of the Chrysler Corporation? CHARLES FLEMING profiles the legendary high-stakes gambler and former aviator who parks his own car at his $1 billion MGM Grand Hotel

CHARLES FLEMING

he MGM Grand Hotel and Casino is the largest hotel in the world, a 30-story emeraid-green grotesquerie, gaudy even by Las Vegas standards. It has more than 5,000 guest rooms, which means you could sleep in a different room every night for years without ever sleeping in the same one twice. Employing more than 7,000 workers, it stands on 112 acres that are densely packed with a theme park, health club, eight restaurants, a 15,000-seat sports arena, 171,500 square feet of gaming areas, Las Vegas's only monorail, and an animatronic homage to MGM's most famous movie, The Wizard of Oz.

The owner of this extravaganza, sitting quietly in one of his restaurants, ordering a second J&B on the rocks, and choosing the fish, looks like just another Las Vegas medium to high roller: black slacks, black loafers, white shirt without a tie, and a light windbreaker. No jewelry. He keeps a Timex, without the band, in his pocket. His presence is not commanding.

Most of the waiters and waitresses in his casino and hotel don't recognize him. The ones that do seem pained by his nonchalance. "He comes in from tennis, for lunch, still in his tennis clothes. All sweaty and stuff," says one MGM Grand waiter.

That unassuming manner masks a legendary determination. At age 78, Kirk Kerkorian has owned airlines, the MGM and United Artists movie studios, and a slew of hotel-casinos. Right now, he is in dogged pursuit of a new prize: the Chrysler Corporation, America's third-largest automaker. With $1.3 billion tied up in Chrysler stock, a failed takeover attempt already behind him, and the company bunkered against another assault, Kerkorian refuses to give up the chase.

Over the last two decades Kerkorian has come to resemble a caricature of himself, as if somehow his countenance had merged with that of the lion on his beloved MGM logo. His sweeping mane and ferocious arching eyebrows are gray. His intense dark-brown eyes, set in a deeply creased face, seem to have stared down too many competitors under too much desert sun, though they often preside over a wide, loopy smile. His ears are a cartoonist's dream. Years of tennis and daily three-mile runs have kept his 5-foot-11-inch frame light and fit. On his feet, he looks 15 years younger than he is.

Although Forbes calls Kerkorian the 31st-richest man in America, he travels without an entourage. He parks his own car, instead of using the valet, at his $1 billion hotel. He pays for dinner out of a fold of cash wrapped around a couple of credit cards, secured by a paper clip. True, the former aviator has always had a personal plane or jet—although he hasn't piloted himself in more than 10 years and misses it. He uses a 193-foot luxury yacht, the October Rose, as his office when he travels on business and as his hotel room when he travels for fun.

He avoids the limelight. Almost allergic to the press, he has not sat for an on-the-record interview since 1971. He paid Barbra Streisand $20 million to inaugurate the MGM Grand with two New Year's Eve shows. It was the social event of the 1994 Vegas season. Everyone was there: Alec Baldwin and Kim Basinger, Mike Myers, Andre Agassi, Sydney Pollack, Prince— everyone except Kerkorian, that is.

Those who know Kerkorian know him as soft-spoken, gentle, and, above all, a "gentleman." The word is used over and over—by Alan Ladd Jr., who ran Kerkorian's declining MGM and UA studios, by actress Priscilla Presley, who dated Kerkorian in the late 1970s, by Maureen Donaldson, who was Cary Grant's girlfriend when Grant and Kerkorian were close friends. Even former Hollywood mogul Jerry Weintraub, who was fired by Kerkorian as chairman of UA, calls him "a terrific guy.

A wonderful guy." Adds George Mason, a Los Angeles attorney and fellow Armenian-American who has known Kerkorian since the late 1950s, "He's the most deferential guy I've ever known."

One man who does not describe Kirk Kerkorian as deferential or a gentleman is Chrysler chairman Robert Eaton. Last fall he told a reporter, "Mr. Kerkorian has absolutely destroyed two companies: Columbia Pictures and MGM/UA. It would be a tragedy to let him and his group do that to Chrysler."

But Kerkorian is a hard man to stop. As Vegas bakes in 100-degree heat and Kerkorian's many, many customers throw their money into slot machines and onto blackjack tables, he finishes his scotch and orders vanilla ice cream for dessert, shrugging off his remarkable run of good fortune. Unlike Howard Hughes—to whom Kerkorian is often compared for his wealth and near-reclusive shyness—he didn't inherit a fortune from his father. "I'm just a poor kid from Fresno who got lucky," he says.

Like everything about Kerkorian, that statement is disarming, but also disingenuous.

y the time Kerkor Kerkorian was four, in 1921, his father, an illiterate Armenian immigrant, had become a land baron in California's great San Joaquin Valley. Reckoned some to be a millionaire, Ahron Kerkorian owned hundreds of acres of ranchland and grape orchards in Delano, Fresno, Clovis, and Parlier. His son has described him as the toughest man he ever knew. Aram Betkijian, who sold newspapers with young Kerkor, remembers Ahron as "a big, husky man, a big, rough man who didn't take anything from anybody." His wife was "gentle, small, very sweet." The family was closeknit, spoke Armenian at home, and socialized principally with other Armenian farm families. Kerkor, the youngest of the four children, greatly admired his older brothers, Nishon and Art. His sister, Rose, is the namesake of his yacht.

Kerkorian makes these tupid deals and he always comes out richer.

Born into wealth, Kerkor would also experience poverty. By 1923, following a series of failed business transactions, Ahron was broke. His lands were foreclosed or sold to pay debts. The family moved to Los Angeles, where, in one rented home after another, Ahron tried and failed at various businesses. But, like his youngest son after him, he was an entrepreneur with a gambler's nerve. Within two years, Ahron had found success again, this time as a fruit vendor in the San Fernando Valley.

Still, his father's difficulties must have left a deep impression on Kerkor, soon known as Kirk. He spent his childhood contributing to the family finances by hawking newspapers, caddying, picking melons in the Fresno fields, working in Bakersfield packinghouses, and, at one point, hauling rocks for 40 cents an hour at the grand MGM studio—a studio he would one day own.

"We ran with a tough bunch of kids," Betkijian recalls. "We'd be in jail if we'd stayed with those guys. [Kirk] didn't look for problems, but he wasn't afraid of anything." In the seventh grade, Kirk was tossed out of Foshay Junior High School for fighting and sent to Jacob Riis, a school for bad boys. He soon dropped out altogether and spent the remainder of his teens working odd jobs and training for a career as a boxer. Kirk had a strong right arm, which he hoped would make him rich and famous. Another childhood friend, Leo Langlois, remembers, "He'd make his right hand into a fist and say, 'Leo, this is going to bring me a million dollars in Madison Square Garden.'"

"He got into boxing because they got five dollars a night—quite a bit back then. But it was a hard way to earn it," says Norm Hungerford, another childhood friend.

As an amateur, Kirk won 29 of 33 bouts and earned the nickname "Rifle Right Kerkorian," according to his biographer, Dial Torgerson. He saved money to buy a professional boxer's license, with the simple ambitions, he has said, of having enough to eat and perhaps owning an automobile.

Hungerford also recalls that Kerkorian loved the movies and used to sneak into theaters every chance he got. Evidently Kirk fancied himself a young Robert Taylor. When he and Hungerford went to Sunday-night dances, he would wear a black felt hat to capitalize on his resemblance to the movie star.

very interesting life has its defining moment. Kerkorian's came in the fall of 1939. He had worked for several months installing heaters with a Louisiana man named Ted O'Flaherty. Every day at lunchtime O'Flaherty would take flying lessons. Kerkorian would sit on the ground eating his paper-sack lunch, wondering what O'Flaherty got out of flying and politely declining his co-worker's persistent offers to take to the sky. One day, he gave in.

He never looked back. He immediately abandoned his boxing plans and returned the following day with a fistful of his hard-won savings. It took him less than two years to get himself hired as a civilian flight instructor.

By the summer of 1943, he was a flight captain for Britain's Royal Air Force in Canada. (Like many adventurous and independent American men of that era, he flew for the R.A.F. to make money.) Around this time he married a dentist's secretary, Hilda Schmidt, known as Peggy.

Kerkorian spent most of World War II delivering Canadian-built Mosquito bombers to England. It was solo transatlantic flying, and dangerous, but paid an extraordinary salary for the time—$1,000 a month or more. He was able to save much of his pay, and after the war was over he began to buy military-surplus junkers that had been left in remote places, fly them out, and sell them.

By 1947, Kerkorian had $50,000 in the bank. He used it to purchase the Los Angeles Air Service, which owned three planes, and began ferrying gamblers to Las Vegas, Reno, and the horse track at Del Mar. He plowed his profits back into new airplanes, indulging his love of flying, building his business, and—in imitation of his high-roller passengers—gambling. Legend holds that by the late 1950s it was not unusual for him to win or lose $50,000 in a single night. Years later, after he had quit the casinos, he admitted that he'd gambled heavily for 25 years without ever really making any money at it.

As his business grew, his marriage failed. He and Peggy were divorced in 1951. Three years later he married Jean Maree Hardy, a blonde Las Vegas showgirl. Their first daughter, Tracy, was born in 1959. Kerkorian kept building. By 1962 his charter-airline business boasted its first jet, a refurbished DC-8. Now calling the company Trans International Airlines, he flew charter groups to Hawaii and highpriority military packages around the world, quadrupling his earnings in less than a year.

But despite his success, Kerkorian was at an impasse. In a field of companies that were becoming giants, he didn't have sufficient funds to grow bigger. Demonstrating a finesse that would later distinguish many of his business deals, Kerkorian sold TIA to Studebaker in a stock swap that would net him nearly $1 million, according to Dial Torgerson. He then sold his Studebaker stock on the street and used the money to buy his airline back from the car-maker for $2.5 million. Then he took the company public, paid off his bank loans, and covered his original cash investment—while retaining 77 percent ownership of the airline.

It was dazzling deal-making. When he sold the bulk of his TIA stock to Transamerica in 1968, he netted $85 million. By the time he sold the remainder, in 1969, he had made $104 million. Ron Del Guercio, who sat opposite Kerkorian throughout the Transamerica negotiations, concluded, "He's got ice water in his veins."

"Were Armenians. Wre warriors. We don't give up."

Howard Hughes was the next businessman to come up against Kerkorian's sangfroid. In 1968, Kerkorian announced plans to build the International Hotel in Las Vegas. Hughes, who operated out of the Desert Inn and owned much of the famed Las Vegas Strip, was outraged. He dispatched his key aide, a tough exF.B.I. agent named Robert Maheu, to scare off Kerkorian. Maheu first tried to convince Kerkorian that underground atomic-weapon tests in Nevada would knock down any building as big as the International. (Hughes knew this was absurd, though he was genuinely terrified of radiation fallout.) The threats, though not physical, gradually "got a little rougher." All the while, Maheu says, Kerkorian was exceedingly polite, but he "wouldn't budge."

"Hughes always said, 'There's not a man I can't buy or destroy,'" Maheu recalls. But as Kerkorian's resolve hardened, Maheu says, Hughes's admiration increased: "He'd met the man he couldn't buy or destroy."

Kerkorian's company, Tracy Investment-named after his firstborn daughter, just as his current company, Tracinda, and his charity organization, Lincy, are named after Tracy and his second daughter, Linda—turned its original $16.6 million International Hotel stake into $180 million in less than five years. He would use this fortune to make a second financial assault: on Hollywood.

"1% yi" GM, the "Ars Gratia Artis" studio, with IVits signature roaring-lion logo, had once claimed to contain "more stars than there are in the heavens." By 1969, when Kerkorian began acquiring shares, it was practically defunct. But Kerkorian was not interested in saving MGM out of sentiment or for art's sake. For him, Hollywood was purely business.

In 1978, expanding his movie-industry portfolio, he bought 25 percent of Columbia Pictures as a friendly investor, with the proviso that he not increase his stake beyond that level for at least three years. Two years later, claiming Columbia had failed to "consult" with him as per their agreement, he attempted to do just that. Columbia subsequently bought Kerkorian out, at a premium it had set when he made his initial investment. Kerkorian's $43 million had turned into $134 million, but Columbia executives and board members would later claim that Kerkorian had greenmailed them.

The same would be said of Kerkorian's investment in Western Air Lines, in which he had begun acquiring stock in 1968. By 1976 he was demanding three seats on the board and had forced out the chairman of the company. Management decided it was time to buy back Kerkorian's shares. It did so, but at 18 percent above market price.

Kerkorian's explanation is that the company had attached a right-of-first-refusal clause to his shares, which prevented him from selling them on the open market unless Western passed. His critics claim that he threatened to sell his shares to a Western competitor, who was willing to pay the premium. The greenmail charge has dogged Kerkorian ever since, and some assume it to be the motive behind all his investments, even though, in a later, failed takeover attempt on Disney with investor Saul Steinberg, Kerkorian was offered greenmail and refused it. Kerkorian vehemently denies all greenmail charges.

Kerkorian's investment in MGM—and later in United Artists, the studio founded by Charlie Chaplin, Douglas Fairbanks, D. W. Griffith, and Mary Pickford—is what made him a billionaire. But Kerkorian never assumed the trappings of a Hollywood mogul. He neither tried to learn the movie business nor seemed to enjoy its glamour. Alan Ladd Jr., who worked for Kerkorian as a movie executive from 1985 to 1988, says Kerkorian occupied a tiny office, and, though he loved going to the movies, he didn't read scripts, attend meetings, view rough cuts, or even take part in screenings (Continued on page 146) or premieres.

Continued on page 146

Continued from page 94

Mort Viner, an ICM talent agent, remembers that when MGM released That's Entertainment! he and Kerkorian went to Westwood and stood in line to see the movie. "Everything with Kirk is understated," says Viner, who knows how unusual such modest behavior is in Hollywood. "He does not want to be conspicuous or take advantage."

Alan Ladd Jr., who can't think of a single instance when Kerkorian asked for a special screening, or passes, or even an invitation for himself or his two daughters or any of his friends, concludes, "I don't think he enjoyed being part of MGM or UA. What he liked was owning a movie studio that was for sale. And we were always for sale."

That's why half of Hollywood—the half that never knew him personally—hates Kirk Kerkorian. He is widely viewed as the man who wrecked MGM and UA, who bought a majestic Hollywood legacy and sold it piecemeal. The 1990 book Fade Out: The Scandalous Final Days of MGM, written by former MGM production executive (and now Variety editorial director) Peter Bart, called Kerkorian a "one-man wrecking crew" who "transformed corporate demolition into a high art."

T ike everything else in Hollywood, this ⅝ J take on Kerkorian's MGM legacy is a mix of reality and fantasy. MGM was already a wreck when Kerkorian began acquiring shares. In 1970, it commanded a feeble 4 percent of box-office market share, dead last among the major studios. In 1977, after Kerkorian had upped his stake to 51 percent, it held an 18 percent share, second only to Twentieth Century Fox. By then, Kerkorian had opened the old MGM Grand hotel in Las Vegas, and was fueling film production with casino revenues. He subsequently separated the two companies, acquired United Artists from Transamerica and merged it with MGM, and began a series of transactions so complex that the Los Angeles Times could only refer to them as "bewildering."

Potential buyers came and went. Kerkorian tried to acquire all the outstanding shares of MGM in order to take it private and was rebuffed. He sold the MGM library of films, including such classics as Gone with the Wind, The Maltese Falcon, and Casablanca, to Ted Turner to raise cash. He also sold his Las Vegas and Reno hotels to Bally Manufacturing in 1985. (Several years later he built the current MGM Grand.) Ted Turner bought MGM/UA for $1.5 billion and then couldn't complete the financing.

When the dust had settled, the studio's assets were scattered horribly. Turner sold the MGM lot to Lorimar. Kerkorian bought back MGM, its logo and name, and all of United Artists, and Turner was left with only the lucrative MGM film library. Though 1989 brought MGM/UA an Oscar-winning hot streak with Rain Man, A Fish Called Wanda, and Moonstruck, Kerkorian was frustrated. He wanted to get out of Hollywood.

Eventually a new buyer surfaced, an Italian named Giancarlo Parretti, who was owner of the Cannon and Pathe film companies. As is now known, he was also a crook. In a highly unusual series of deals orchestrated to close in a single day, Kerkorian sold Parretti the UA film library, which included the James Bond, Pink Panther, and Rocky films, for $625 million. Then Parretti sold his companies Pathe and Cannon to Kerkorian for, coincidentally, $625 million. Then Parretti paid $1.4 billion to buy all of MGM/UA, which now included the two companies he had just sold to Kerkorian. November 1, 1990, was a busy day.

Profitable too. Not only was Kerkorian free of Hollywood, he was walking away with more than a billion dollars. The studio, however, was a financial wreck, and its assets all wound up in the hands of Credit Lyonnais, the French state-controlled bank whose Dutch subsidiary was forced to fund its bailout. Kerkorian may have seen the sale to Parretti as creative deal-making, not unlike his earlier transactions involving TIA, but Credit Lyonnais claimed that it was fraud—that Kerkorian knew the Pathe divisions he was buying with MGM/UA money were not worth what he paid for them, and that he had merely sought to cash out at top dollar.

Parretti, released after 35 days in a Los Angeles jail, now faces perjury charges. Kerkorian, eager to proceed with his Chrysler bid and loath to face a protracted trial, was forced several months ago into an out-of-court settlement with Credit Lyonnais that reportedly cost him $125 million. (Kerkorian's lieutenant Alex Yemenidjian, president and chief operating officer of MGM Grand, Inc., calls that figure "ridiculous," but says that the terms of the settlement preclude him from disclosing the actual amount. However, a reliable source close to the settlement confirms it was around $100 million.) And in Hollywood, Kerkorian's name is anathema.

Friends say that it pains Kerkorian terribly to know that anyone anywhere thinks ill of him—and that it pains him especially that he is not remembered fondly in Hollywood. It is the only topic that causes him to lose his temper, according to several employees and friends, who claim that otherwise they have never heard Kerkorian raise his voice. "[Turner] sold the fucking [MGM] lot—not me," Kerkorian complained recently. "That bullshit still goes on."

Perhaps he remembers his time in Hollywood as a happy one. He and his family lived in large homes in Bel Air and Palm Springs, where Kerkorian, who is described by longtime friend George Mason as a "B-minus or C-plus club tennis player," spent a lot of time on the court. Kerkorian had a busy private life during this period, though he would not legally separate from Jean until 1981. There was a friendship with Priscilla Presley, with whom he visited England during the summer of 1977—the summer that her estranged husband, Elvis, died. There was a long friendship with actress Yvette Mimieux. Kerkorian would jet off to Europe with his actress friends* frequently in the company of pal Cary Grant and Grant's girlfriend of the moment, in an L-1011 specially outfitted with telephones, an office, and a marble bathtub, and stocked with Chateau Lafite. He'd take the October Rose to Cannes for the film festival there, and continue on to cruise the Mediterranean.

But then, as now, Kerkorian maintained a low profile. "Kirk had real charisma, but his sexiness was his humility," says a woman who knew him. "He wasn't boastful or bigheaded. He was nice ... a man of extraordinary grace." She adds, "He loved Jean very much, and he was very discreet. But he was quite a womanizer." Says another woman of this period in his life, "He was a terribly sweet, bluecollar guy." Whenever there was a disagreement with a woman friend, he'd resort to simple, working-class solutions: "O.K., knock it off," he'd say.

Today, Kerkorian's private life is less racy. He is saddened by the fact he has no grandchildren. He remains devoted to his sister, Rose, and has a close-knit circle of chums. He's still friendly with Mimieux, though their relationship ended 20 years ago and she is now married. Even Priscilla Presley says through a spokesman, "Kirk is a friend now and has been for many years."

Unfortunately the latest object of his affections, Chrysler, does not regard him so fondly.

T n December of 1990, Kerkorian J.bought 22 million shares of Chrysler stock for $272 million. The stock, trading at around $12, had no significant expectations. Even Kerkorian's longtime aid'es were confused by the move. "It was the stupidest thing I ever heard," says his employee of 25 years James Aljian. "When he bought 10 percent of Chrysler, everyone said, 'He's finally lost it,"' echoes key aide Alex Yemenidjian, a dark, handsome Argentinean-born shoemaker's son.

As part of Kerkorian's team of very close advisers—one who has performed many of the company studies that Kerkorian insists be reduced to one-page summaries before he'll read them—Yemenidjian now explains it this way: "It was his sense about Lee Iacocca," who was then running Chrysler. Aljian agrees: "He thought Iacocca was a fine manager, and this was a great company." They did not know, then, that Kerkorian would ultimately make a bid for the entire company. Neither, both insist, did Kerkorian.

Eventually, though, in true Vegas fashion, Kerkorian pressed his bet. He bought his second chunk of shares—six million—in October 1991, when the stock had fallen to $10.12 a share. He bought another four million shares at $38.75 in February 1993. By this time Kerkorian owned roughly 9 percent of the company, with the stock trading as high as $63.50 in early January 1994. To date, Kerkorian's cash investment totals $1.3 billion; on paper his Chrysler holdings are worth $2.75 billion.

In the wake of Iacocca's departure in 1992, Kerkorian continued to maintain that he had "a very high regard" for the Chrysler management, which was now headed by chairman Robert Eaton. But in the fall of 1994, despite the fact that Chrysler posted record earnings for the year, its stock fell into the 40s as a result of investor worries that car sales were due to slump in the new year. Kerkorian sent a stern letter to the Chrysler board demanding that certain measures be taken to bolster the stock price. The board acquiesced for the most part and Kerkorian pronounced himself satisfied, then set about buying four million new shares.

Then he decided to buy the company.

Alex Yemenidjian insists that from November 1994 up to his actual bid, in April 1995, Kerkorian had many conversations with Chrysler management about a takeover, and was told each time, "This is intriguing. Let's have another meeting." Yemenidjian claims that under Kerkorian's plan "management would have cashed out tremendously on their options, and they'd start out fresh with a 5 percent stake." Chrysler executives insist that they told Kerkorian the company was not for sale. They refuse to discuss the situation further on the record.

A Chrysler insider tells a different story. He says that during the preliminary discussions Kerkorian "was being heavily encouraged" to proceed, and that he "had reason to believe" management supported the idea. However, the insider says, Kerkorian was being "misled." Chrysler's motives in this are unclear. The insider lays the blame on Chrysler chairman Eaton, who, he says, is "a superb car manufacturer and a superb leader . . . [but] is not familiar with the ways of financial takeovers."

Wall Street insiders point out that, whatever Chrysler was saying to Kerkorian, it should have come as no surprise to him that an entrenched board of directors would not support a friendly buyout. "[Kerkorian's people] were incredibly naive to think that after a few conversations over a four-month period they had an understanding," says the Chrysler insider.

T hen Kerkorian made his bid, on April 12, to pay an estimated $22.8 billion to take over the company, Chrysler management did not take long to reject it. "We do not want to put Chrysler at risk," said Eaton.

In his three years as chairman, Eaton had presided over one of the most spectacular turnarounds in modern corporate history. Because it was almost universally conceded that Eaton was doing an exemplary job, Kerkorian badly needed to give his takeover attempt credibility. He needed to demonstrate that a takeover would improve the company, rather than just take cash out of it. It was clear even to the assembly-line workers that a buyout would load Chrysler with debt and drain its cash reserves—a move that would enrich only the stockholders.

Anticipating such fears, Kerkorian sought to allay them by joining forces with his friend Lee Iacocca. He and Iacocca had met in 1989, at a Florida racetrack during a lunch arranged by investment bankers. According to Yemenidjian, the two men hit it off immediately. Iacocca remembers that Kerkorian said to him, "I'll bet $300 million on you."

The 70-year-old Iacocca, who owned a mere $50 million worth of Chrysler stock, agreed to lend his name and his reputation to Kerkorian's takeover attempt. Some assumed he was taking revenge on Chrysler for "retiring" him. As it turned out, though, Iacocca proved ineffective as a figurehead. Few at the car company were eager to see him backeven in an "advisory" role. (Indeed, Chrysler would eventually sue Iacocca, claiming he had divulged confidential business and financial information to Kerkorian. Iacocca calls the charges "wild and off-the-wall fabrications.")

Within weeks, Kerkorian's bid had collapsed into something of a public humiliation. He had needed to raise at least $12 billion from banks or other corporate partners, but none ever surfaced. The United Automobile Workers said they would work with Chrysler to derail the bid. Other Chrysler shareholders were largely skeptical of Kerkorian's motives. Worst of all, on April 19, Kerkorian's Wall Street representation deserted him when, after pressure from Chrysler, Bear, Stearns & Company ended preliminary discussions with Tracinda.

At this point another investor might have gone home to lick his wounds. Not Kerkorian. Although his takeover bid has degenerated into guerrilla warfare, no one seems to be counting him out just yet. On July 26 he spent $700 million to buy an additional 3.7 percent of Chrysler's stock—a signal to Chrysler and to the world that he was not going away. While Kerkorian has yet to escalate a proxy fight that might seek the ouster of all 13 members of the board, he has replaced Iacocca as his marquee name with Chrysler veteran Jerome B. York.

York worked at Chrysler for 14 years before going to IBM, where he became chief financial officer. He says he got to know Kerkorian during "14 to 15 hours of talking last July and August," which persuaded him to come on board at Tracinda. Driven and smart, York is already making speeches about Chrysler's "complacent" management. A source claims that York has reversed his positions on Chrysler policies "180 degrees" and that "$25 million from Kerkorian made him change his mind." (York denies that he has altered his positions.) Kerkorian is now fighting to install York on the Chrysler board, where, presumably, he could undermine Eaton from within.

It is difficult to figure out what Kerkorian's final goal is with Chrysler. He flatly rejects the notion of a greenmail attempt; in fact, he has repeatedly said he wouldn't take it even if it were offered. Perhaps he is waiting for an economic downturn, when he can convince Chrysler shareholders that they should oust Eaton.

A Chrysler insider points to a preliminary proxy statement filed by Tracinda last December to show that Kerkorian still intends to take over the car company. Buried in that document is Tracinda's fee arrangement with its financial adviser Wasserstein Perella & Co., which stipulates a bonus of $12.5 million "upon the consummation of . . . a purchase by Tracinda or any of its affiliates of a majority of the then outstanding voting securities of Chrysler . . . [or] a merger or consolidation involving Tracinda or any of its affiliates and Chrysler . . . [or] an asset transfer by Chrysler of all or a substantial portion of its assets to Tracinda .. . [or] the election of, or the acquisition of the right to elect ... at least a majority of the directors of Chrysler, without the vote of any other shareholder." A source close to Chrysler believes that, "having always been considered a maverick or a pariah, Kerkorian is seeking legitimacy, and owning a blue-chip company would accomplish that."

At the very least Kerkorian hopes to get at Chrysler's nest egg: $6.4 billion in cash reserves put aside as a safety net. Kerkorian and York contend that hoarding that amount of cash is unnecessary, and unfair to shareholders, who deserve some $5 billion of it. Chrysler and Kerkorian's detractors say that amount is the minimum needed for protection against a dry spell in sales or a downturn in the economy. (As evidence, they point to the estimated $4.5 billion it took to weather the last recession.)

Manhattan-based money manager Seth Glickenhaus attacks Kerkorian as "the most self-serving guy to ever happen on the scene. He's looking to take out a lot of cash in a hurry." A Manhattan-based attorney associated with Chrysler is more blunt: "His record is replete with examples of activities that have served the Kerkorian agenda but not the rest of the shareholders. He always sucks cash out of companies."

Tracinda Corporation has numbers to dispute that. According to its calculations, the TIA transaction, from May 1965 to May 1968, yielded investors a compound annual return of 117 percent. The Flamingo and International Hotels investments, which went public in February 1969 and were sold in July 1971 to Barron Hilton, yielded a return of 64 percent. Tracinda puts the MGM yield—from 1969 to 1986, including the sale of the two hotels—at 15 percent. And MGM Grand, Inc., which went public at $10.05 a share in February 1988 and was recently trading at more than $25, yielded a 12 percent annual return, according to Tracinda.

Kerkorian's deals, though, often seemed the work of a confused man. Says a person who calls Kerkorian the Forrest Gump of finance, "Who wanted Chrysler? Who wanted an airline? Vegas was dying when he started building [the new] MGM Grand. MGM was a piece of shit when he bought it. He makes these huge, stupid deals, and he always comes out richer."

Aside from the fact that anyone imitating Kerkorian would have seen a decline in the growth on his investment from 117 percent with TIA to 12 percent with MGM Grand, there is another problem with the equation: those percentage yields do not necessarily reflect what Kerkorian himself earned.

1¾ /T GM HEAD TALKS TO MAFIA, read the IVJ_ January 15, 1970, front-page headline of the New York Post. The accompanying story revealed that Kerkorian's voice had been picked up on a 1961 government wiretap. In more than 50 years of business dealings, this was Kerkorian's one visible stumble.

On the tape, Kerkorian was heard telling a mobster named Charles "Charlie the Blade" Tourine that he was sending him a check for $21,300. Kerkorian would endorse the check and send it to actor/tough guy George Raft, who would cash it and give the money to Tourine. Kerkorian didn't want Tourine to cash the check himself, he said, "because the heat is on."

Although it was subsequently demonstrated to the satisfaction of the authorities that the money was payment for gambling debts, and although "the heat" turned out to be regulatory issues that would have created difficulties for Kerkorian had he been, in fact, tied to the Mob, the tarnished reputation stuck.

That's not what law enforcement says. "I have never heard his name mentioned in connection with any impropriety," says a retired member of the Las Vegas Organized Crime Unit. Says another expert on the subject, "It's an indication of how naive Kerkorian is about that stuff. Everyone in the world knew George Raft was half a wiseguy. He was Bugsy Siegel's partner! And Kirk asked him to pay a gambling debt."

At the time of the Post's revelation, Kerkorian, who had loans coming due, was perilously close to disaster. He had asked the Securities and Exchange Commission to allow a secondary public offering of shares in his International Leisure Company, which owned the International Hotel and the Flamingo Hotel. The Justice Department put the nine-year-old wiretap together with the Flamingo's notorious past—it had been opened by Bugsy Siegel—and effectively blocked the offering.

In a desperate attempt to raise cash, Kerkorian sold his 9,000-square-foot Las Vegas home and his personal DC-9, and put his yacht on the market. His total assets fell from a high of $553 million to an estimated $91 million—a figure that would not have covered the loans coming due. To pay his tab, Kerkorian was forced to sell controlling interests in the International and the Flamingo to Hilton Hotels.

Kerkorian was baffled by the turn of events. He had always been, as a friend puts it, "in the language of the world he moves in, a real stand-up guy." He is now, his personal assistant Steve Scholl says, "a dinosaur in the business world. A handshake is all the deal he needs."

Kerkorian claims that his handshake has always been his bond. Alex Yemenidjian tells of making a deal in 1990 to sell the Desert Inn to a group of Japanese investors for $185 million. No papers had been signed when a competing offer came in, for $200 million. Yemenidjian called Kerkorian to tell him about the new offer, and was met, at first, with silence. Then Kerkorian said, "Why are you calling me? You gave your word."

Armenians are perhaps the most fiercely cohesive of America's ethnic minorities, and Kerkorian's Armenian heritage is a source of immense pride to him. His two closest aides—Aljian and Yemenidjian—are of Armenian heritage, and Kerkorian has donated huge sums of money to Armenian charities. His ethnic pride even guides, to a degree, his business deals. After Tracinda failed to acquire Chrysler outright last spring, Yemenidjian said, "We're Armenians. We're warriors. We don't give up." Perhaps Kerkorian thinks of himself not as a corporate raider but as a warrior, although, as one businessman who knows Kerkorian points out, "there isn't a single raider out there who thinks of himself as a raider."

T ike many men of his age, Kerkorian -Licomplains that life and the world around him have changed—for the worse. When he first flew into Las Vegas, in the summer of 1947, it was a lovely, small town of 27,000. "It was fun. You knew everyone," he told an acquaintance recently. Now it's too big and too fast and too mean, for which Kerkorian knows he is partially responsible, along with Howard Hughes. Both spent hundreds of millions of dollars to make this bleak desert city the grotesque oasis it is today.

Unlike Hughes, Kerkorian isn't crazy and he isn't quitting. He shows no sign of diminished capacity or appetite. He is an avid tennis player and he tries to run three miles daily. Those close to Kerkorian say he appears unruffled, his deeply tanned, deeply lined poker face showing no anxiety. Asked recently if he had a credo, he shrugged and told an acquaintance, "Work like you'll live forever. Play like you'll die tomorrow."

He is perhaps beginning to think of his legacy. Filings with the S.E.C. show that over the next four years Kerkorian will donate $550 million—in the form of 10 million shares of Chrysler and 2 million shares of MGM Grand—to charity.

Confirming the amounts, Yemenidjian says, "You just can't wait until the very end to give away $3 billion." Why the sudden decision? Has Kerkorian recently received any bad news about his health? "No," Yemenidjian says. "It has nothing to do with his health. He just woke up one morning and said, 'What am I waiting for?"'

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now