Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowHarmed Lives

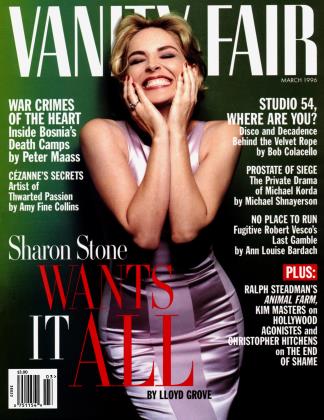

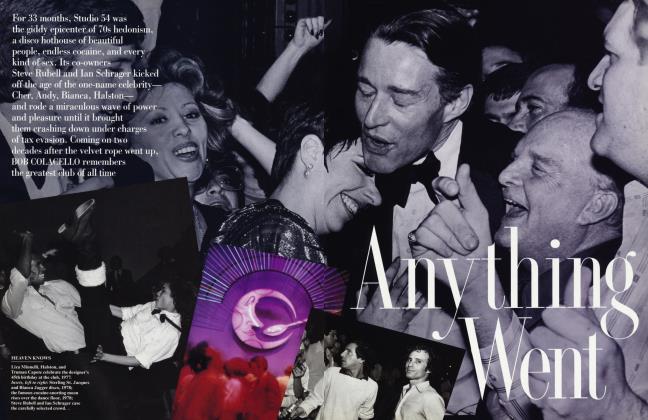

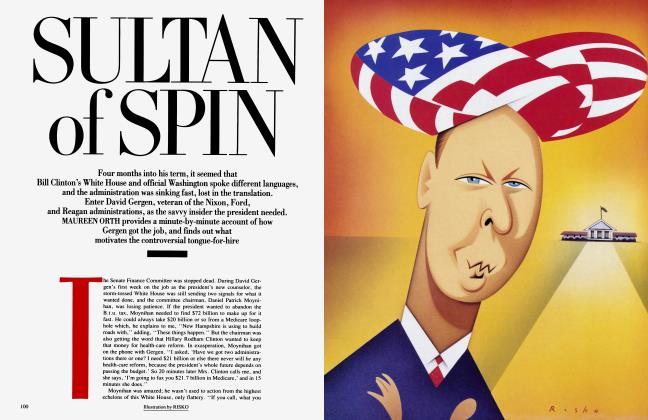

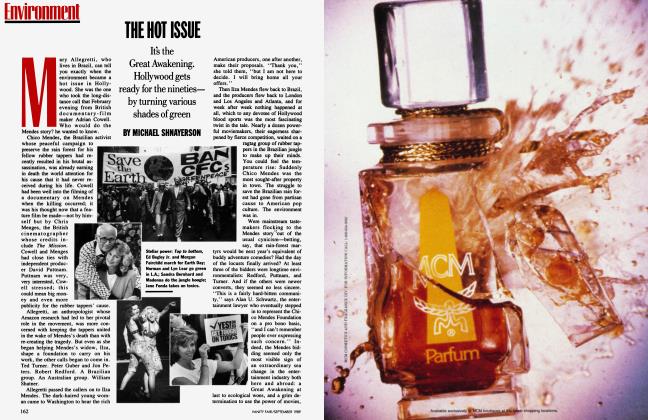

When Michael Korda, Simon & Schuster's dashing editor in chief, wasn't racing Porsches or horseback riding with his wife, Margaret, he was publishing—and writing—a string of best-sellers. He didn't expect to become a poster boy for prostate cancer. From Korda's account of that ordeal, Man-to-Man, due out this spring, and from the author and his friends, MICHAEL SHNAYERSON learns about the private perils of one of publishing's most charismatic figures

MICHAEL SHNAYERSON

Frail, diminished, he still loves to talk. He has a thousand glittering stories he could tell you without pause, about Richard Simon and Max Schuster, S. J. Perelman and Jacqueline Susann and Graham Greene, Richard Nixon and Ronald Reagan. If he were a prisoner using them to allay his executioner, he could stay alive for weeks. Tonight, over dinner in a dark restaurant, Michael Korda puts them aside to speak with no less fervor about the prostate cancer that jeopardized his life in late 1994, but over which he triumphed, after a major operation, and about which he has written a most extraordinary book.

As Simon & Schuster's longtime editor in chief, as editor himself of such superstar writers as Mary Higgins Clark and David McCullough, and as a best-selling author in his own right {Power!, Queenie), Korda has been one of publishing's most visible figures for decades. Literally he has been on view almost every lunchtime at the Four Seasons, where his average yearly bill throughout the 1980s reportedly was $24,000, and where his usual was a baked potato, a side of creamed spinach, and a nonalcoholic beer. Yet his public persona, so brilliantly facile, has always hidden the actor within. In Man-to-Man, which Random House will publish in May, the actor emerges, vulnerable and shaken, to tell a story not only more compelling than his commercial fiction but also bravely—startlingly—frank.

Unlike Norman Cousins's more ruminative books on illness, to which it will doubtless be compared, Man-toMan is a spare, straightforward account of what happened to Korda, from first warning signs to diagnosis of prostate cancer, operation, and recovery. Told with no self-pity, though with frequent flashes of wit, it is a graphic guide for fellow sufferers, a great read—and the most important writing of Korda's career. Already it has made him, as he puts it wryly, the poster boy for a cancer that badly needed one. (Each year nearly 250,000 American men are diagnosed with it. Francois Mitterrand and Time Warner's Steve Ross are among its bestknown victims, Bob Dole and Norman Schwarzkopf just two of its famous survivors.) And having dared to discuss the intimate issues that the disease involves, Korda speaks of them now with the heady sense of freedom exposure can bring.

"Men who undergo this operation suffer for quite a while from [urological] incontinence," Korda says blithely as we raise our glasses in the 30thfloor private restaurant of the Manhattan tower where he sleeps two nights a week. Despite his ordeal, he retains, at 62, a boyish energy, distilled in a tiny, wiry frame with constantly gesturing hands. Ingratiating, confiding, he still seems oddly detached, a cool pro in the practice of charm. The difference is that he used to entertain. Now he's a proselytizer, consumed by the subject that nearly did him in.

In most cases, the operation causes not only incontinence but also impotence. Korda says he's begun to show signs of recovery in that regard as well, but not enough to rule out the prospect

that injections, an implant, or other measures may have to be taken. "Of course, whatever way you go, you're not going to have any emission. . . . That alone is going to make sex different," Korda avers. "Worse? Not necessarily. Different."

Any cancer dramatically affects the life of a patient's mate. But the impotence resulting from a radical prostatectomy, even if temporary, creates a special strain. In Man-to-Man, Korda quite rightly makes his wife, Margaret, an equal partner in his story, depicting her emotions throughout as unflinchingly as he does his own. In fact, as a good novel sometimes reveals more about its author than its author intended, Man-to-Man offers along with its tale of illness and recovery a portrait of a marriage—one that has stirred curious speculation in publishing circles for more than a decade.

It was on a day in October 1994, Korda writes, that he learned he had cancer. Stunned, he went to his horse farm in upstate New York to talk over his options with Margaret, his wife of 16 years. "I can't believe we're having this _H_conversation," Margaret says

in the book after Korda makes her a drink. "Yesterday we were talking about going to Santa Fe for Thanksgiving and Christmas ..."

The verdict seemed so unfair. Korda had always stayed trim and fit, riding and jogging regularly. He kept to a rigorous diet, drank little alcohol, no longer smoked. Weren't health freaks immune? Nor was there any history of cancer in his family. As he immersed himself in the literature, however—an obsessive editor's reaction—he learned that in one study men who had undergone vasectomies were found to be nearly twice as prone to prostate cancer as those who had not.

Korda had gotten his vasectomy soon after he and Margaret were married. "I went into it, I have to admit, with a certain ambivalence, as most men probably do, but had no complaints about the results when I eventually healed," Korda writes in Man-to-Man. "Still, from time to time, in moments of crisis between us, the subject of my vasectomy occasionally arose, usu-

ally from me, as in, 'Remember what I did for you,' to which Margaret would respond that I had agreed to it of my own free will—the truth, for what it is worth, lying as usual somewhere in between."

The vasectomy, however, seems but one example of a peculiar eagerness on Korda's part to please his wife at any cost—a desire that might seem admirable if Margaret were not, according to some of Korda's friends, a strikingly cold and self-absorbed woman. "Is she an ice maiden?" asks one friend. "Is it sexual? Is she a dominatrix? Everyone speculates. Nobody knows."

At New York's Memorial SloanKettering Cancer Center, Dr. Paul Russo made clear to the Kordas that there was no time to waste. The only question was who should perform the operation: Dr. Russo or Dr. Patrick C. Walsh of Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore.

Both doctors were first-rate. Walsh, though, was a superstar, whose reputation as the leading prostate-cancer surgeon in the U.S. was based in no small part on a method he had pioneered to remove the prostate without severing the nerve bundles that help control erections. Richard Snyder, Korda's colleague and boss of almost 35 years, whose tenure at S&S had come to a sharp end not long before with Viacom's acquisition of S&S along with the rest of Paramount, put Korda in touch with Ken Aretsky, coowner of New York's Arcadia restaurant. Aretsky had chosen Walsh for his own operation in 1993 and was, like most of Walsh's patients, a fervent advocate. "I'd lie down in front of the taxi that's taking you to the hospital to stop you from going to anyone except Pat Walsh," Aretsky declared.

Korda liked Russo enormously. But Aretsky and others were persuasive. Didn't it at least make sense to go meet Walsh? Margaret was not so sure. "I knew she

didn't want me to," Korda writes. "I could tell that she liked Russo (as I did). And I could guess that she didn't want to drag this experience out, that her own nerves were already at the breaking point. Besides, if I was going to have the operation ... it would be much easier to do it in New York than in Baltimore. Margaret could stay in the apartment, as opposed to camping out in a strange city in a hotel. . . . One look at Baltimore by night," Korda adds, "was enough to convince Margaret that she didn't want to spend a week or ten days in a hotel here, away from home, her friends and her animals."

The Baltimore option, which Korda did choose finally, despite Margaret's misgivings, would mean merely a week in a hotel. Even so, Korda writes in the book, "the one issue over which Margaret had proved difficult was the amount of time she would have to spend in Baltimore, away from her home. I had finally delegated to a friend the task of explaining that we simply had to fly down to Baltimore Sunday evening, at the latest, even though it was theoretically possible to reach Baltimore in time for our appointment on Monday by leaving New York early in the morning of the same day."

Over dinner, Korda fidgets when this passage from the manuscript is raised. "I may change that," he says, "because I talked to Margaret, and while there's an element of truth to it . . . some of what I attribute to her not wanting to go to Baltimore were things she was bringing up to slow me down in my decision not to go with Russo."

argaret has been playing a dominant role in Korda's life ever since the two met in the mid1970s, when both took morning horseback rides in Central Park. "We rode in opposite directions," Korda recalls. "One day, we started riding in the same direction." Each was married—Korda to a former secretary named Casey, with whom he had one son, Christopher, now a computer programmer in Boston; Margaret, in her second marriage, to photographer Burt Glinn. British-born, Margaret had ridden horses from early childhood and come of age in 60s London, where novelist Peter Forbath remembers her as one of the great beauties of her time. She had moved to New York with Glinn and modeled for him—in liquor and airline ads, among others. But one day, about the time Korda met her, she looked at the two dozen pieces of camera equipment she

and Glinn were to take on yet another long-distance job and announced she didn't want to travel anymore for work. For more than a year, she and Korda conducted trysts in hotels. One day, Korda later told a friend, Margaret showed up at his office at Simon & Schuster. "I've left Burt," she announced. "I'm yours."

If the affair seemed tinged with the glamour of Hollywood drama, that may not have been by chance. One friend suggests Korda has always seen his life as a movie, consciously crafting its upcoming scenes, striding into them with Leslie Howard-like flair, and then performing. He is, after all, a child of the Hungarian-Jewish moviemaking Kordas, his father, Vincent, the art director of The Thief of Bagdad, Summertime, and others, his more famous uncle, Alex, the London-based mogul who controlled much of the British film industry before and after World War II, producing such films as Anna Karenina, The Scarlet Pimpernel, and The Private Life of Henry VIII. Warner LeRoy, the restaurateur, recalls getting to know Korda when both were teenagers and stuck in the infirmary for a week at the exclusive Swiss boarding school Le Rosey. "It was just after the Third Man movie came out," LeRoy says of one of Alex Korda's great successes, "because he played that damn score over and over again. ... He was this sort of wonderful young English fop, rather fashionable, very much fun, but of a different century. I kept wondering what would happen to this boy."

Korda has always seen his life as a movie, striding into its scenes... and performing.

Close friends found the marriage dramatic indeed, though not quit^ in the way the Kordas might have hoped.

Korda's mother, Gertrude Musgrove, had surely helped instill in her son a sense of life as drama. A Britishborn actress, she had left Michael with a nanny in Los Angeles when the boy was eight, right after she and Vincent were divorced, and moved to New York to pursue her stage ambitions; Michael soon followed her, and in one of his visits to her dressing room was entertained by a stagehand named Issur Demsky, whose own dreams of acting came true after he changed his name to Kirk Douglas. Within a year, however, Uncle Alex became Michael's unofficial guardian, sending him on to Oxford after Le Rosey. As a result, Michael did not see his mother for more than a decade. Photographs of her reveal an uncanny resemblance to Margaret.

By the time Michael met Margaret, a whirl of other scenes, all cinematic, had occurred. A stint in the Royal Air Force. A journey to Hungary to join, if only briefly, in the uprising of 1956. A first job in America, teaching waterskiing in Florida. An offer of work from Henry Simon, Richard's arts-minded brother, at the then small, gentlemanly Simon and Schuster, where Korda sat at a desk facing the wall until Robert Gottlieb, soon to become S&S's editor in chief, helped him turn the desk around, telling him to make his presence felt if he wanted to get ahead.

Gottlieb's departure to head Alfred A. Knopf in 1968 enabled Korda, at 36, to succeed him—but, thinks Gottlieb, only reluctantly. "Michael was the one who stood to gain the most from my going, yet my impression was that he was really distressed by it," Gottlieb recalls. "I don't think he ever wanted to be in charge; he just wanted to do his own things, and didn't want someone else telling him what he could or couldn't do." In a sense, his role would remain fixed from then on: a run of remarkable duration in a business ever more marked by change. For the poor relation of a glamorous but unconventional family, a steady job, with growing dividends, also seemed a way to establish an identity of his own.

Yet Korda was, as one colleague observes, a Korda, and within the ordered life he'd created for himself, he needed new roles and new dramas, all to be recounted in ever more colorful detail: he was, as one former colleague suggests, always mythologizing his own life. "I remember his rodeo period," says LeRoy. "That included riding broncos. . . . Then, of course, the motorcycle period, during which he attended Harley-Davidson conventions." Korda raced Porsches and Ferraris. He collected guns and shot birds and took pride in his pistol license, which is difficult to procure in New York City. And always he rode horses, which allowed him to stride into corporate meetings in jodhpurs and boots. In his office, to impress—or perhaps depress—impecunious writers and editors, Korda displayed prominent photographs of Margaret and himself riding, of the two on safari in Africa, of Margaret in a bikini. This was a life well lived, the pictures conveyed, a life of luxury and success, of hard work and fun. A life of drama, with Michael Korda the star.

lose friends found the ^ marriage dramatic B } indeed, though not quite in the way the ■ Kordas might have hoped. "Everyone jokes about how MarA garet orders Michael around," says one friend. "Dick ordered him around, too, by the way; he loves that." "She's this gorgeous, cold horseback rider who clearly fulfilled some sort of fantasy he needed," suggests another. Opinion was divided on the fantasy's consequences. "Michael loves this myth that she's a loving wife when in fact he's the loving husband," declares one friend. Others discerned a powerful bond. "They're very mutually dependent," says one friend. "She also adores him," says another. Writer Sidney Offit, a friend of many years, says, "She represents for Michael a romantic vision, and, not uncharacteristic of romantic relationships, there is something in the impulse that's mysterious."

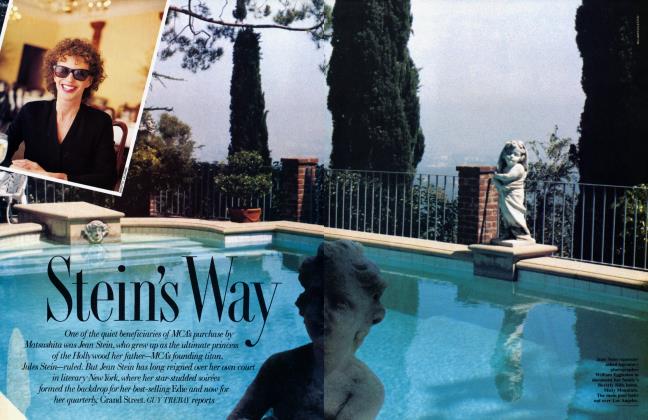

The Kordas bought a large Dutchess County property (Continued from page 167) in 1980 that now includes 200 acres, and Margaret set about transforming it into a horse farm, complete with indoor riding ring. Eventually they sold their Central Park West apartment as Margaret spent more and more of her time upstate, training for and competing in regional events. (They also own a home in Santa Fe.) "Among the other consequences of that marriage," says one friend, "is that she took him out of circulation. Michael Korda, who knows everyone! He's invited to the Kissingers'—he doesn't go!"

(Continued on page 205)

But Korda clearly enjoyed the country life. More than that, he loved his work, and was wonderfully good at it. "He's terribly smart, he has a great education, a memory like a steel trap, and a range as broad as any editor could possibly have," observes editor Alice Mayhew, Korda's

colleague of some 20 years. "He's also incredibly fast. He can read faster than I can turn the pages." David McCullough turned in Truman at well over 250,000 words, expecting to hear back in two or three months; Korda read the book and made detailed suggestions in three days. Though he employed a series of assistants to help edit the books he acquired, Korda was a graceful line editor himself, as well as an idea man. For Mary Higgins Clark, Korda would come up with plot twists over meals.

Korda was not, however, the sort to cultivate sensitive young novelists who might one day become great writers. ("Michael is an efficient editor," says one ex-colleague, "not an inspirational editor.") Frankly uncomfortable with literary fiction, he always felt strongly that his job was to nurture Simon & Schuster's bottom line with such commercial writers as Clark, Clive Cussler, Harold Robbins, and Jackie Collins. In this, he served as a perfect foil to Dick Snyder, the hard-driving,

sometimes brutal publisher who had guided S&S's great growth and subsequent sale to Gulf & Western. "In 35 years of working together," Korda declares, "there was never a cross word between us." Snyder, whose outbursts with others were legend, concurs. "We were always careful because the relationship was so valued," Snyder says, "and we never trod on each other's skills." Korda, Snyder adds, also had "a great head for numbers."

Joni Evans, whose tenure at S&S in the 1980s included marriage to and divorce from Snyder, with a period as head of S&S's trade division in between, agrees with her ex-husband about Korda, if nothing else. "In my years," says Evans, now a successful senior vice president and literary agent at William Morris, "Michael had the cleanest profit-and-loss statements, the most extraordinary return on investment, of any editor at S&S. He was like a thoroughbred. He could turn anything into gold, even if (Continued from page 205) he had to write it himself. ... He was always a storyteller, an actor, a scriptwriter; he had all the talent of performance and the genius. Applied to books, it was fantastic."

(Continued on page 208)

A mong younger editors at S&S, Korda commanded somewhat less respect. He was a remote, self-interested figure— "not very reachable," concedes editor and contemporary Nan Talese—who, when he deigned to attend editorial meetings, spent his time drawing automobiles on yellow legal pads; his own, big-money acquisitions he preferred to clear privately with Snyder. Younger editors could be coldly, if perhaps unconsciously, snubbed. "When I met him," recalls one, "Joni [Evans] brought me around and introduced me. I held out my hand. He never took it; he never looked at me. Instead, he said to Joni, 'Joni, we must discuss the cover for Queenie.' Finally, I just withdrew my hand."

By then, Korda's second career, as a writer, had consumed any time for office nurturing he might have had. Nan Talese, as an editor at Random House, had bought his first book, Male Chauvinism!, a curiously earnest and perceptive jeremiad on sexism in the office. "I couldn't believe that any man was writing what was actually true," Talese recalls. "It was shocking— and refreshing." From that came Power!, a big best-seller that appealed to the paranoid in every executive. Korda advised his reader to adopt such stratagems as sitting with one's back to the window in an office so that others would have to face the glare of the sun; at lunch, he urged, the successful power player should "gradually [move] his pack of cigarettes, his gold Dupont gas lighter, his reading glasses, his butter plate and water glass, if necessary, closer and closer to the center of the table, finally crossing the invisible boundary until they encroach on your [partner's] table space." Korda later claimed to have written Power! strictly as a commercial gambit, but he had clearly given serious thought to the maneuvers suggested in it. One of his luncheon partners, a woman, recalls making a point of sitting to one side of him because her vision was better in one eye than the other. Korda was fascinated. "Now, come on," he kept saying. "Why did you really want to sit on that side? What does it mean?'''

From the exclamation-point series (the last was Success!), Korda went on to his universally praised family memoir, Charmed Lives, then, to the surprise of his friends,

turned to commercial fiction. "I always had it in mind that writing consisted of writing novels," Korda says. Having edited mass-market fiction for so long, he seemed also to see it as a game he could play. "He's thrown his mind away on those novels," one editor says. Says another, "When you read Judith Krantz you feel she believes this stuff. Michael was just turning it out."

Still, Korda's first novel, Worldly Goods, about an eccentric Hungarian billionaire, did so well that Snyder insisted that Queenie, his next, be published at S&S. Korda readily admits there was some awkwardness in the editor in chief's being published by his own house, but Queenie, a roman a clef about Merle Oberon, was a best-seller, and a five-hour mini-series of the book followed. A new novel was contracted at more than four times Queenie's $250,000 advance. Korda was at the very top of his career. And it was at this point he was introduced to a new woman editor at Simon & Schuster who would play a leading role in the next scene of his life drama.

60 he was very attractive," says one

O former S&S editor, "and the rumor was that she always got her jobs on her back. So all the women were in a catfit over her." Another ex-colleague remembers, "She was like a sorority girl in cashmere and spike heels. Powerful men just keeled over for her, and she had affairs with several of them. The irony was she was a good editor. It was just a shame that she felt she had to be linked to—and protected by—older, successful men."

In fact, the young editor had been at S&S nearly two years when she and Korda began their affair in 1988. It was a tumultuous time overshadowed by the angry personal and professional breakup of Snyder and Evans, which culminated with Evans's departure for Random House, and her replacement, as head of S&S trade, by Charles Hayward. Never really involved in management, Korda stayed well out of the administrative fray, in an office, not insignificantly, a curving corner away from the "murderers' row" of the other, competitive S&S editors. But in taking up with the young editor at last, he created his own turbulence, or, as one S&S editor puts it, "a bizarre piece of nonsense, some sort of playacting, for what purpose I have no idea."

The young editor was married, with a small child, but seemed to fall hard for Korda; he was, as she told one friend, all that she imagined an urbane New York editor could be. At a sales conference,

one of the periodic corporate meetings held at posh resorts, Korda and the young editor astounded their colleagues by strolling arm in arm on a moonlit beach in Florida in full view of the hotel patio above. The couple was often observed having romantic lunches at midtown restaurants, and word of the affair spread through the publishing community, but Korda seemed oblivious, a man in love.

In retrospect, Male Chauvinism! seems to have been written by Korda as a prescient warning to himself. "Every office has its famous affairs," he had written, "and each is usually a legend of triumphant masochism ... the endless, hard-drinking, weepish sessions of manto-man [!] confessional when things are going badly ('I mean, I really love her, but I haven't got the guts to tell my wife. I'm a coward, what would you do?'), the embarrassing moments of tenderness, displayed in highly inappropriate circumstances, when things are going well . . ."

Korda had always been drawn to daring pursuits over which he was required to exercise tight control—from horseback riding to motorcycles to fast cars to guns—but which retained elements of danger and chance. The affair with the young female editor seemed to fall into that category. After nearly a year, some close friends believed that she and Korda were planning to wed as soon as their current marriages could be ended. What the young editor failed to appreciate, however, was the great exception in Korda's life of control: Margaret.

T71 inally, Korda, the female editor later _F told a friend, called Margaret to announce he was in love with another woman. Margaret asked only that he come home to the country to discuss the matter face-to-face. The next day the young editor was called at home and told by either a colleague or Michael himself that Margaret was on the warpath and that the affair was over.

In short order a rumor tore through the publishing industry that Margaret had placed one of Korda's prized guns at his head. Probably it was a detail added by those telling the tale to heighten the drama. (Without elaborating, Korda dismisses the accounts of the incident as inaccurate.) Within the week, the young editor was summarily dismissed from Simon & Schuster by Charles Hayward, albeit with a generous severance package; later she would hear that she had been fired for cause. The firing was "an absolute disgrace," says one who worked at S&S at the time. "The aftermath of most office affairs," writes Korda in Male Chauvinism!, "is the departure of the woman, sometimes forced out by a hierarchy of men whose protective instincts are aroused by the sight of a fellow man in trouble."

The young editor with whom Korda had had the affair never heard from him again. He made no effort to help her find another job. Devastated, she left the publishing field for five years (she is now a literary agent).

"Offices hold many dangers for men of a certain kind and age," Korda had written in Male Chauvinism! "People like this are unprepared for the sudden complexity of an office love affair, and nearly always handle it as badly as possible, paying the maximum amount in exposure and marital stress for the minimum amount of pleasure." For Korda, the breakup hastened a transition he had been planning anyway—of withdrawing from the office and spending more time at home. In his stead and with Evans's departure, Mayhew, whose list included such serious nonfiction writers as Bob Woodward, James Stewart, and Doris Kearns Goodwin, and with whom Korda had always had a respectful but edgy relationship, took on more managerial responsibility. She became, in effect, the dominant editor at S&S. "I liked that sort of thing," Mayhew says, "and I came into the office every day, and incrementally I became more involved." About Korda's marriage, there was, after the fateful weekend, no doubt: he was staying with Margaret, who appeared lounging poolside in a bikini at the next Simon & Schuster sales conference while Korda attended business meetings inside, a few feet away.

Among some of Korda's close friends, there was shock that he had returned to the marriage. One friend, however, saw it differently. "She's extremely jealous and possessive," says the friend about Margaret, "and [Michael] loved that."

Within two years of the affair's dramatic end, close enough to raise the question of whether stress and emotional loss played a part, Korda's prostate problems began.

r 11he operation, though traumatic, was Ji a success; the cancer was removed. In the days following, true-crime writer Rodney Barker, one of Korda's authors (Dancing with the Devil), flew in from Santa Fe, as did Sidney Offit and his wife, Avi. Dick Snyder and agent Morton Janklow, Korda's longtime friend, volunteered to charter a plane for his return to Dutchess County. Weakly, Korda de$ dined. "What a good friend does is offer, I but not push," Snyder says soberly.

In Man-to-Man, Korda admiringly describes Margaret's fit of pique on his behalf with Dr. Walsh, when she felt that a protocol of post-operative painkillers had been administered ineffectively. Some of Korda's friends were less impressed.

"It was just a chance for her to take center stage and throw her weight around," says one. Rod Barker, who joined Margaret a couple of evenings at the hospital, thinks that judgment is harsh. "Michael's not an easy patient," he observes.

"He's usually in control of things." Now, for the first time, Margaret had to be the strong one—a challenge to which she rose, Barker and other friends agree, if, perhaps, belatedly. "I think being married to Michael over the years makes it difficult to judge the place she's come to," he says. "There may have been times when his work seemed the most important thing, and she's had to take second place. Then he has the operation, and you reflect on how much he's put you through. . . .

"In all marriages, there are tradeoffs," Barker adds. "Margaret and Michael have worked things out. I'd be reluctant to judge her behavior without taking the whole marriage into account."

Korda had asked Dr. Walsh if a homecare nurse would be needed after the operation. Walsh had thought not. "Anything I couldn't do," Korda writes, "[Walsh] was quite sure my wife would look after. ... A glance at Margaret," he adds humorously, "was enough to persuade me that in this case, at any rate, Dr. Walsh was being over-optimistic. I did not think Margaret was likely to relish a temporary role as Florence Nightingale."

During December and the first two months of 1995, Korda took daily walks without fail, supported by Margaret at one side and the big male nurse's aide they had hired at the other. As he gained strength, he took on a few urgent projects, such as Nicholas Pileggi's Casino, which had to appear before Martin Scorsese's movie version. At the beginning of March, Korda began going down to the office. He had, he says, an irrational fear of being bumped on the crowded city streets. He feared he might fall, that his incision might open. At the office, he confined himself to an hour in the late morning, lunch and a

rest, a second hour, then back to his pieda-terre on West 57th Street, where he stayed alone for the two or three nights he was in town.

Margaret remained in the country, tending her horses. As usual in early spring, there was so much work to be done to prepare for the upcoming season. Combinedtraining riding, which is what Margaret does, involves dressage, stadium jumping, and cross-country. It's very demanding.

"She's devoted to it," Korda says admiringly. In fact, he adds, Margaret has been a No. 1 rider in the Northeast in her category.

O et just outside the unpretentious town Oof Pleasant Valley, near Poughkeepsie, the Kordas' farm appears, at first glance, to be a modest weekend house. It lies close to the road, in such hilly country that its outskirts are completely obscured. Only when a visitor strolls through the stable into the first of several paddocks, and observes two or three of the Kordas' five horses, does the scale begin to assert itself. In fact, the property is large enough for the Kordas to host their own cross-country event here the first Sunday of every May. Christopher Reeve attended the last one, three weeks before his tragic fall.

"We're at about our limit with five horses because we only have six stalls and we like to use one for storing hay," Korda explains cheerfully as we take a short tour. In jeans and a work shirt, he appears, in the bright light of day, almost fully recovered from his grimmest year. He pauses by a beautiful horse in the nearest paddock. "Here's Star," he says. "We got her last year."

The tour continues inside, through rooms of late-19th-century English furniture, to a curious, shrine-like alcove whose walls are completely covered by horse ribbons—hundreds of them. These, Korda explains, are Margaret's rewards for her endless victories in years of formal competition. Considerable money is needed to train for these events, to travel to them, to enter them. Cash prizes, of course, are not disbursed. One rides for sport—for, as Korda puts it, the adrenaline. "Ah," he says, brightening, "here's Margaret."

A trim, lithe blonde in black cashmere and tights offers a firm, small hand. Perhaps in her late 50s—one senses not to ask—Margaret remains a strikingly attrac-

tive woman with delicate, perfect features and blue, prismatic eyes. A life of outdoor sport has weathered her skin, though her visage seems defined more by the stern line of her thin, pursed lips. This is a woman clearly meant for the saddle, her mount's reins firmly held in one hand, a riding crop in the other.

She leads the way into the kitchen, holding a manila envelope. "Michael, I have to check that you've given me my money." She empties the envelope onto a counter.

"It's exactly what you asked for," Korda says pleasantly. "Or perhaps I owe you more."

"Really?" She examines the check. "I think you owe me less. . . . But not to worry. How long do the banks stay open?"

Korda sets out a sandwich for me, and a small, healthful-looking salad for himself; Margaret, mindful of cholesterol, opts for a plain, untoasted bagel, which she picks at with dainty fingers as we settle into comfortable chairs in Korda's study. Over the fireplace, I can't help noticing, is a single-barreled shotgun.

Talk turns to horses, as it often does at the Kordas'. "Michael had said to me when he was getting ready to go into surgery—I had just lost a horse—[that] it would be a very good idea if I got myself a new horse," Margaret explains. "A project. Something to work on. It got close to Baltimore, and I started to seriously look. I finally bought the horse [Star] in January. ... So this year I kind of concentrated a lot on that."

The only nice part about Korda's operation, Margaret explains, is that it happened in winter, which is a quiet time for horses. By early April he was recovered enough for her to begin traveling every weekend, often from Thursday to Sunday night, to the events in which she competes up and down the East Coast clear through to Thanksgiving. On the midweek days he was down in the city, she saw no point in joining him. "I come down for what I call maintenance, to get my hair done, my nails, or go to see a doctor," Margaret explains, "but I don't like the city very much."

The whole ordeal of Michael's cancer,

I suggest, must have been harrowing; as Korda says repeatedly in his book, the spouse in some ways suffers more than her husband.

"It was a very harrowing time," Margaret agrees. "My emotions weren't the same from one 30-minute period to the next. ... I remember going through whole cycles. Anger that it was happening, because it would change everything, relief it wasn't me, fear that Michael might

die. . . . And sometimes—we were going to the hospital a lot in New York—I would just remove myself, just get in the car and come up here. Just take time out and ride."

Fortunately, Margaret says, she had a great support group around her. "The people I'm with every day, the people that work in my bam, and my part-time housekeeper ... all were made aware of it straightaway. That way it was no big deal; I'd talk about it every day with them, and they'd talk about it with me. When there were tears about it, there'd be tears about it together."

Still, Margaret was shocked to realize how vulnerable she suddenly was, "because, you know, Michael looks after me all the time." Margaret flashes a prim smile at her husband. "I have always been looked after, wouldn't you say, Michael?"

Korda nods, his feet not quite touching the floor from the bench on which he sits. "Certainly by two of your husbands. I don't know about the first one."

Among the emotions, I wonder, was there any twinge of guilt or regret about the vasectomy?

"No," Margaret says. "I have to be perfectly honest with you."

So it was just something that seemed right at the time?

"It was the way we wanted to live," Margaret says. "Michael has a son by his first marriage. And I don't really like children, so we didn't want any more, and I was tired of being on the Pill."

frhough Korda still owns guns, he no X longer hunts. "I used to love bird shooting," he says. "And I'm a pretty good shot. Margaret's a very good shot." He remembers, "I suddenly decided I don't like this. I like eating pheasant, and I'm not against killing things. I just didn't want to do it anymore myself." Korda does retain his membership in the N.R.A., however. "That doesn't mean I agree with the N.R.A. on everything—I never have," he says. But, he adds, "I'm a life member.

I don't know how you resign from it."

Since the operation, Korda has been more productive as a writer than many writers are in a lifetime, not only turning out the book in mere months but contributing elegant reminiscences of Jacqueline Susann and Graham Greene to The New Yorker. To his shock, and that of the entire publishing world, he also succeeded in selling the movie rights to the seven-page Susann piece to TriStar films for $750,000.

Thin as its narrative thread is, the Susann piece seems to have appealed to Hollywood in part because Korda portrays himself as the young editor he was with Susann, trying to keep an overblown showbiz icon on track—much like the young narrator in My Favorite Year. Only the pettyminded, perhaps, would cavil at the license Korda may have taken in telling the story: Susann did not, according to one source, direct him to wear Irving Mansfield's jacket to go out to a restaurant called Danny's Hide-A-Way, as Korda depicts, nor did they actually go to the restaurant that particular night—because Korda walked his fellow editor Jonathan Dolger home instead.

As for Barbara Seaman's 1987 biography of Susann, Lovely Me, there is, of course, no reason either Korda or his agent Robert Bookman, of Creative Artists Agency, need have mentioned it to the Hollywood bidders, though Korda's involvement with Susann on The Love Machine is documented in its pages and it might, as a result, have been available for a fraction of the price Korda's article fetched. Such are Hollywood's workings, and Seaman, for one, is fairly philosophical about them. "In a way he did me wrong," Seaman says of Korda, "but he also did me a favor." With the putative Susann revival, Lovely Me has been optioned as a television movie, leaving only the question of which version will appear first.

As an editor, Korda now tries to take on, as he puts it, fewer "birds with broken wings"—books, especially ghostwritten Hollywood autobiographies, sure to entail headaches and revision. At the same time, problems he can't avoid seem less daunting. Even growing old, the prospect of which kept him obsessively fit for years, seems less alarming. He's ready for his 60s; he can deal with them.

"I think if cancer doesn't change you, you have to be a real putz," Korda says. "I'm not saying you have to emerge as St. Francis of Assisi, but you should emerge with a more profound view of mortality— and more tolerance—than you had before. I find I simply don't let myself get upset. ... I do my best to the extent I can. If it doesn't work, it doesn't work."

Graciously, the Kordas walk me to my car. Then, hand in hand, they head over to the stable, Margaret leading the way, and to the horses in the paddocks beyond. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now