Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

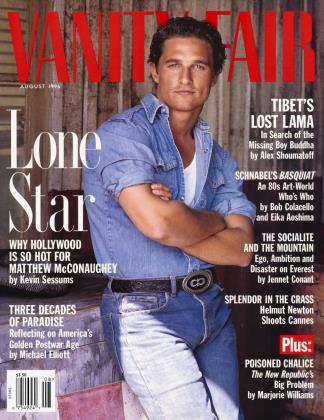

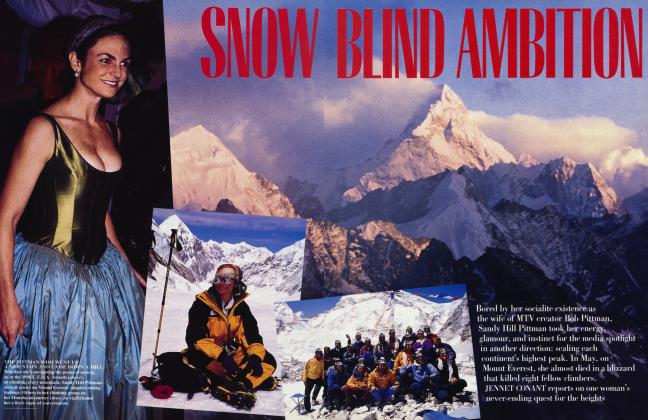

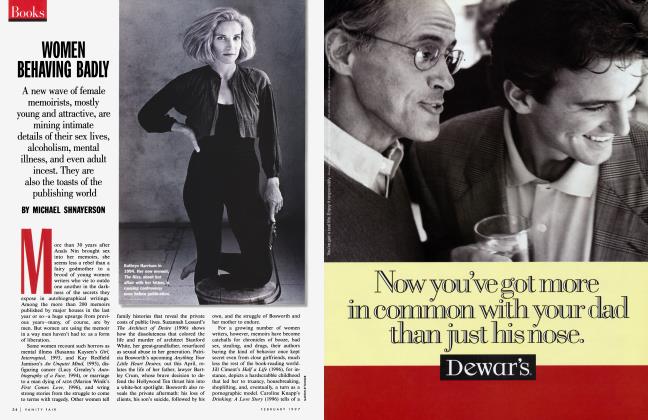

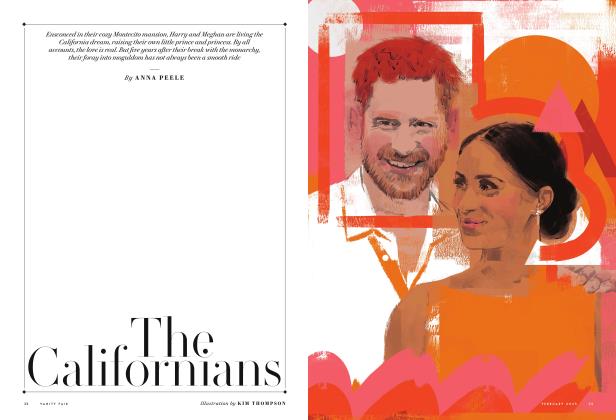

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowSavile Row legend Hardy Amies, knighted by the Queen for his service as her couturier, has been making well-bred clothes for half a century, His brilliantly tailored tweeds are fresh again, MICHAEL SHNAYERSON finds, and his wickedly eccentric wit is sharper than ever

DRESS ME, HARDY

FOR DETAILS, SEE CREDITS PAGE

Sir Hardy Amies fixes his American visitor with an impish look. "What are you wearing? Armani, I suppose?"

A not-quite Armani, as it happens. A knockoff.

"Look at where the bottom coat button is," Amies commands.

His visitor looks down.

"Genitalia fastening," crows the elder statesman of British clothes-makers. "You can't have fastening buttons below the waist."

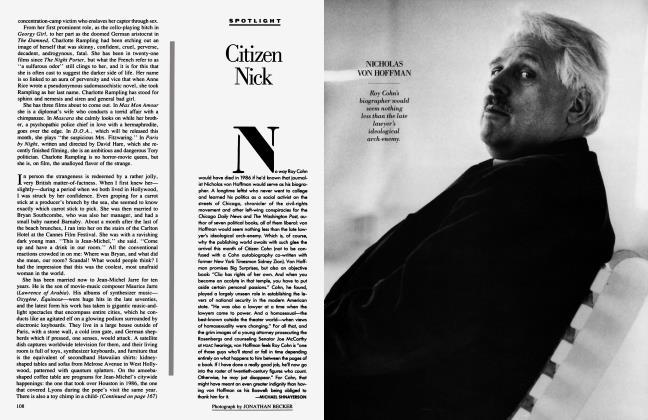

Just over 50 years ago, Hardy Amies moved into this war-ruined town house at 14 Savile Row and began making clothes by the rules and traditions of the tailors on the street. There, with a knighthood to honor his service as couturier to the Queen, he remains, his mind and wit undimmed at 87. He still subjects every new design to coruscating judgment. His sensibility still informs every item of clothing that bears the Amies label. And he still throws brickbats at other designers with mischievous glee.

At times, Amies's adherence to tradition has put him so at odds with other designers as to make him seem a curio from a case in the British Museum. Yet proper English ladies of the upper classes have come year after year for his soigne country tweeds. And if his women's wear has remained an increasingly rarefied luxury, his men's wear has been taken up by 50 licensees in 14 countries, generating $150 million a year in sales.

Now he's lived long enough to see fashion come full circle. The tightly £ shaped suits and bright formal flous of his latest collections seem taken directly from his first show, in 1946; these are clothes Ingrid Bergman might have worn in Casablanca. Yet with their classic lines and quietly rich fabrics, they're brilliantly contemporary.

"His clothes bespeak a specifically English approach to dressing, which is also aristocratic—to be wary and distrustful of anything that smacks of vulgar fashion," observes Hamish Bowles, Vogue's European editor-at-large. "If an evening dress has a jewel neckline, it's because it's intended to be worn with significant jewels. If a tweed skirt is fitted a certain way, it's done so the wearer can walk across the moors or the turf at Ascot, not because it's the season for that style. But fashion right now is interested in that sensibility."

"In the last year, it's true you've seen those adorable little dresses and suits," says The New York Times's Holly Brubach. "And you see them being done by people who've never done them and don't know how to do them well. Yet here's Hardy Amies, who knows how fabric should be cut and how clothes should fit, who knows how to produce a dress that flatters a woman. ... I think of his clothes as being incredibly well bred. They're almost the fashion equivalent of that clipped, upper-class English accent. Fashion has come around to exactly that—anti-fashion—so it's a great moment for him."

Handsome still, with aquiline features and a full head of hair, Amies was, earlier in life, tall and dark as well, with Cary Grant-like looks in which, to judge from early portraits, he took obvious pride. At a distance—in a photograph, say, by his friend and neighbor Lord Snowdon—Amies, in a hat and gray tweed overcoat, seems a pillar, a caricature almost, of English propriety. This he is, and this he's not. Perfectly mannered hobnobber with the upper orders though he is, he's the first to acknowledge his indifferent birth. "Not bad," he likes to say of his success, "for a suburban frock-maker."

And while he revels in the snobbery that only arrivistes can muster, he knows he's a bit of an act, a oneman drawing-room comedy produced with a spiritual assist from Oscar Wilde. "I'm funny," he says. And he is.

'I was going to take you to Buck's, my club across the street," Amies explains. "But it's frightfully stuffy."

Amies uses a cane, but also keeps a powerful grip on his visitor's arm. Bent over as he is now by a bad back, he retains the large frame that kept him competitive at tennis until last year. His young men's-wear designer, Ian Garlant, appears in an open shirt and casual pants. "How scruffy you are today, dear boy!" Amies says. "I can't imagine what your underwear looks like."

Garlant, after nine years, is still the new recruit. Ken Fleetwood, Amies's design director, arrived 44 years ago, the licensee chief 24, the finance man 51. The House of Amies is the family of Amies, now made more so by its founder's decision to will its members the business as a trust. Even Amies's public-relations man, Peter Hope Lumley, started 49 years ago. A nervous, wheezing fellow in a crumpled linen jacket, he's less a flack than a foil for his boss's gibes. "He's never known how to dress," Amies confides as Lumley pops outside to alert the chauffeur.

Once, Amies had a Rolls-Royce, a 1933 Sedanca de Ville. After two years of constant maintenance, he gave it up. Now he has a Ford Granada Scorpio Estate. He rides in the front passenger seat, as he has in every car he's owned. "That's Buck's," Amies points out. "It was started by Captain Buckmaster after the '14-T8 war [as he refers to World War I] for members of the household cavalry only, and then went wider. Still, I knew damn well when I came here 50 years ago to my shop that the captain—he was alive then—would never have had a dressmaker into his club. Well, the years passed, and they didn't do too well, and someone came and begged me to join." Amies laughs heartily. "I said, 'We'll have to make him a pair of kneepads.' It was Anthony Burney."

"Anthony Burney was a shopkeeper, after all," Lumley says.

"No he wasn't."

From Savile Row, the humble Ford rolls past Wellington Place and through Knightsbridge to 1A Launceston Place, a stylish local restaurant. Amies often goes home to his apartment after lunch to take a nap. In this, his age may be of less account than the inevitable Amies cocktail, a straight-up vodka martini with a twist of orange. "You'll have one, of course," he declares.

"Two and you're flat on your face," warns Lumley.

"You should have the foie gras terrine, and then the lemon sole," Amies instructs.

His visitor requests permission to choose an alternative appetizer.

"Oh, all right, I'll take the same fucking thing."

A waiter approaches with bottled water. Amies waves him off. "I don't want any of that, thank you," he says. "I had a bath this morning." To his visitor he says, with a naughty look, "I saw Bill Blass not long ago. He's gotten very fat, hasn't he?" Blass is an old friend and now Amies's American counterpart, in that his clothes are handled by the same master licensee. He's also, of course, a rival. "Recently, I read he gave $10 million to the New York Public Library," Amies says. "Why? Because he wants to suck up to Mrs. Astor!" (Blass responds to the barb later by phone: "If I'd wanted to curry favor, there would have been cheaper ways to do it than that. The fact is that I've been on the board of the library for 10 years. That's just Hardy Amies being snide; that's his style.")

To any British designer, $10 million is a mind-boggling sum. The House of Amies's profits are relatively modest, since most of its income is generated by its licensees, who pass along a mere fraction. Amies himself lives not in some mansion but in a two-bedroom apartment on the ground floor of a row house in Cornwall Gardens. "I have no money!" he declares, though this is not quite true. What he has is the lifestyle he wants: the apartment, the car, his clothes, money to go to lunch, and six servants.

"Seven, including me," Lumley mutters. "And, of course, the house in the Cotswolds is very nice."

"Have you heard of David Hicks?" Amies asks his visitor. His visitor, alas, has not.

"There you go, so it doesn't matter."

"No, it does," Lumley protests. "David Hicks is Lord Mountbatten's son-in-law." He's also a garden designer and writer whose coffee-table book on Cotswold gardens was recently published in England. Amies's garden is among those pictured. The Duke of Marlborough, the Duke of Beaufort, and Lord and Lady Vestey are just a few of the other distinguished Cotswold cottage tenders whose modest horticultural efforts are featured.

"He's such a snob," Amies whispers to his visitor as Lumley ticks off the names.

"I don't need to be one," Lumley huffs. Lumley is a nephew of Captain Edward Molyneux.

"You're a media snob—you like names."

"Come on," Lumley says heatedly, "who drops seven dukes in a single sitting?" To his visitor he says of Amies, "He's a social snob, a garden snob, and a wine snob. It's part of his charm."

"It depends what you mean by snob," Amies says. "The best way to put it is that I'm an elitist. I admire enormously the English upper classes. They are nice people who look after their estates; they certainly look after the servants on their estates. And they have a very civilized way of living, which they would willingly share with other people."

Like many outsiders who have risen as far as they can in England, Amies adores the cold calculus of class even as it finds him lacking. Successful and talented as he is, worldly and well read as he has become, he cannot help who his parents were (father was a government land surveyor; mother worked for a court seamstress), or where he went to school (Brentwood). Even his knighthood, conferred upon him on his 80th birthday, has not made him an aristocrat to a wellborn duke oi duchess. Amies knows that; he e> pects it. He also expects not to be stigmatized in any way for his station. "If anybody makes me feel uncomfortable because I wasn't born in the upper class," he says, "or that I wasn't mad about women—let's not go into that—they would lose out, and not me."

Knighthood is, however, as close as one can get to erasing the stigma of class, and Sir Hardy's is rather a high one: Knight Commander of the Royal Victorian Order. Queen Victoria established the order in 1896 to honor citizens of venerable service to her. Though below the Orders of Bath,

St. Michael, and St. George, it's above the political knighthoods granted by the prime minister, as well as those bestowed among the arts.

"Now, I have friends who have genuine titles in the sense that they genuinely inherited them," Amies says modestly. "One girlfriend is the descendant of an earl. She said you speak it—your title—as little as you can.

"Fashion has Come around to anti-fashion— so its a great moment for him."

"He'll say outrageous things and then whisper, Darling, do you think I got them going?'"

I said, 'I've always thought so.' She said you never ring up and say, 'I am Sir Hardy Amies.' Except perhaps at a restaurant, where it's terrible fun."

The service for which Hardy became Sir Hardy began, he cheerfully recalls as cocktails are followed by a bottle of New Zealand sauvignon blanc, on July 2, 1951. Well established by then on Savile Row, Amies counted among his customers a lady-in-waiting to Princess Elizabeth. So taken was Elizabeth with her friend's smart clothes that she arranged to pay a visit to 14 Savile Row, where Amies, in his private office, showed her his latest collection.

The princess who came to the shop that day, and whom Amies attended soon after at Clarence House with sketches adapting his designs to her, was a young woman of generous bosom and slim waist who knew what she wanted: bright clothes to cheer a postwar nation still garbed in austerity black. Clothes with a "princess line" that ran from shoulder to hem without a waist seam to draw attention to her female shape. Clothes, above all, that wouldn't crease during a long day of public appearances. "She dresses for her audience," Amies declares reverently. "That is the secret of good dressing."

Amies has long since steeled himself to public snickers about the Queen's attire, though he still feels the press is unfair. Designer Arnold Scaasi, who has dressed three First Ladies, agrees. "It's very difficult dressing the head of state," he says. "There are certain limitations on what they can and can't wear. I think he's done a wonderful job."

'We know the Queen doesn't always photograph well, and we're distressed about that," Amies says. "[But] everyone who has been present [when she appeared] thought she looked lovely." One critic, though, has gotten under his skin. "There's a man in New York named John Fairchild," he says of the powerful publisher of W and Women's Wear Daily. Amies's quarrel with him goes back to the late 1960s, when the House of Amies designed a uniform for British Airways flight attendants that met with disapproval. Not surprising, Fairchild reported, given that Amies designed dresses for that "dowdy Queen." Amies rebuked him for his rudeness to his sovereign in a frosty note, and there until recently the matter lay, since Fairchild, notorious for banishing designers from his pages, could do no harm to a British designer whose customers never saw the American fashion press, much less heeded it.

"The Queen doesn't always photograph well, and we're dis tressed about that."

Over time, Amies's licensing chief, Roger Whiteman, befriended Fairchild's wife, Jill. Mightn't the hatchet be buried? he asked Amies. Fine, Amies agreed. He invited the Fairchilds for drinks at his apartment, then took them, along with Whiteman, out to dinner. All went well until Fairchild started in again about the Queen. "I said what I'd said before," Amies recalls, "that she's not a fashion plate; all she asks is to be dressed for the occasion. He said, 'What does she look for in clothes?' 'Friendly, chic clothes,' I said. So he went back and wrote a whole page in W against me about 'friendly, chic' clothes." Most wounding, Fairchild wrote that in Amies's apartment before dinner he had been given a whiskey without ice. Amies was outraged. "The first thing I do to fix a drink is put some ice in a glass," he says. "But anyway, what a rude thing to say about someone who's invited you to his house!"

Fairchild's piece is actually rather lighthearted and fun. About Amies, its author is bemused. "Sir Hardy's a very fine gentleman but he's been living off the reputation of dressing the Queen for years, and talking about it—never off the record," Fairchild says. "Yet when others write what he's said, he objects." Still, it annoys the publisher that Amies failed to voice his displeasure directly. "He could have called me," Fairchild observes. "Instead he did it the snide way, through you."

About Amies's place in English fashion, Fairchild is blunt. "He knew how to make a great suit, and that sporty, quite English look which has sometimes bordered on the dowdy. But to put him up there in the league with any of the great designers—Armani, Saint Laurent—is ridiculous." Even among English designers, Fairchild suggests, Sir Hardy ranks low. "He certainly wasn't a creative designer like John Cavanagh, or Vivienne Westwood, or Jean Muir."

The late Muir, as it happens, comes up in conversation over coffee. "I loved her," Lumley declares. "I loved having her in the house."

"My God, what a beast," Amies says.

"Oh please, no, don't," Lumley remonstrates.

"Well, apart from that irritating verbal tic she had ..."

"She loved you," Lumley says.

"We met up once in Germany and it was a disaster. We shared a car with her. She had one of the most dreadful verbal tics: she'd finish every sentence with a sort of hmm?"

"I admired her," Lumley says fiercely.

"Roy Strong said, 'Isn't it awful about Jean Muir?' I said, 'What's awful? She died. That was the best thing that could happen. The only thing worse than a male bore is a female bore, and she was a female bore.'"

Women designers generally earn Amies's sharpest gibes. They've never designed clothes as well as men, he feels; they never will'. This is because women make clothes for themselves, whereas men can be objective. The great exception, of course, was Chanel. "She had a man's mind," Amies explains. "She was a toughie—she knew exactly what was going on. She was absolutely of the period. And everything she did was based on a man's coat."

Amies bridles when the word "misogyny" is mentioned, and quite rightly: his own feelings toward women, after a lifetime of clothing them, are far more complex, a mix of adoration and scorn based to some extent on how they fit into his clothes and how many of them they buy, as well as on whether they're working women (bad; clothes designers, worse; Margaret Thatcher, worst) or pampered aristocrats (good; titled ones, better; Queen, best). One of his closest friends is Ann Boyd, who started just out of art school in Amies's workshop as an assistant to the Queen's vendeuse and now runs the design firm Reed Boyd. "He really understands women's bodies," Boyd observes. "He would never embarrass a woman; he would never want her to go out looking less than her best." His put-downs, she says fondly, are part of his act of being "a terrible old man. We'll go to parties, and he'll say outrageous things, and as we're leaving he'll whisper to me, 'Darling, do you think I got them going?'"

His homosexuality he doesn't deny; indeed, Amies's early openness showed moral courage, even if, as one British journalist observed, a gay dressmaker in mid-century England serving royals was shielded from prejudice. But being gay was never something one discussed in proper society. Amies lived quietly with one man for 22 years, but when he went out socially, the lover stayed home. "If someone rings you up and says, 'Can you come to dinner?' " Amies told The Guardian in 1994, "the worst thing you can do is say, 'Can I bring my friend?' It is just too common for two men to go around together."

Outside, a handsome young man in blue jeans and a work shirt walks by. Amies puts his coffee cup down and gazes at him, mesmerized. Every elitist, he likes to say, has his day off. Certainly the designer, his visitor observes, has not lost his eye for youth and beauty. He issues a lascivious grin. "That never goes away, does it?"

After lunch, Amies retires as scheduled while his visitor returns to 14 Savile Row, where the second-floor showroom is fast filling with ladies eager to view his latest collection. Ken Fleetwood, a languid, gray-haired man in his 60s whom Amies calls "the boy," hovers by the door, greeting late arrivals. "Welcome," he whispers, "to the parrot house." For all of London's younger designers—John Anderson (who started with Amies), Catherine Walker, Bruce Oldfield, Amanda Wakeley—this is the last couture showroom, and, since the closing of Hartnell's four years ago, the last real English couture house.

Most of the 100 women at the show are English; most are "of a certain age," as Fairchild puts it. But here, too, are a few pairs of demure young wives. None of Amies's regular customers like being singled out, but the grapevine suggests that Raine de Chambrun, Princess Di's former stepmother, is one, Lady Faringdon another, and that, of the younger royals, Princess Alexandra and the Duchess of Gloucester have been known to buy a suit or two. As the music begins and the buzzing subsides, it's easy to see why. The brilliantly tailored suits, in rich earth-tone tweeds, seem to have been poured onto the models who wear them. Amidst them, the occasional silk and satiy evening gowns punctuate the show with bold solid colors: pistachio green, lemon yellow, tomato red. They strike a timely blow against black, and make vibrantly clear that their guiding spirit, napping as he may be at the moment, is still happily alert.

It is true, however, that more and more Sir Hardy's life is lived not here, nor at his apartment, but in his quite marvelous Cotswolds compound, to which, being a sociable fellow, he tends to invite guests.

Promptly at 10 o'clock Friday morning the chauffeur draws up to the Cornwall Gardens apartment, and Sir Hardy appears at his door. Behind him is a living room dark in morning light, with an ancient oak sideboard, a comfortable sofa, and a wall of books. Cozy, but modest. Sir Hardy whispers to a visitor, out of the chauffeur's earshot, "I wanted it to look like a queer don's."

Sir Hardy was born on Elgin Avenue in Maida Vale. Yet he has little to say about the neighborhood as we pass through on our way out of London. His fondest first memories, Amies says as London recedes, are of the vicarage on the Rhine where he lived with a high-bourgeois family in the late 1920s and learned German. Not yet 21, he also spent formative time in Berlin nightclubs and came to share his host family's excitement about Hitler. "Oh, I came back an ardent Nazi!" Sir Hardy exclaims. "It was very silly—I quickly changed. But it didn't appear to do with anti-Semitism, and I was so busy learning about life that I wasn't very interested in politics."

His mother's work had always interested him, and though he never did learn how to sew, instinctively Amies understood fabric and color. By late 1933 he was proficient enough to be asked to manage Lachasse, one of London's most successful new dressmakers. On the racks of the shop's back closets he found ladies' suits ("called suits by the common people; the gentry called them coats and skirts") designed by the talented manager who had just stormed off, Digby Morton. So fresh and strong were Morton's ideas that Amies was profoundly influenced, and has, in a sense, applied them ever since, with grateful acknowledgment.

"His secret," Sir Hardy says of Morton, "was that he took all the necessary features of the man's coatnarrow sleeve, high arms—then softened it by using soft tweeds and avoiding all mannish regressive detail. I don't think he knew enough about the suit to be so fussed about the waist buttons as I am, but ... he was a very important person in propounding what I called the English look."

Sir Hardy's women's wear has been defined by the look for 50 years, so much so that he stirred far more attention by bringing it to men's wear in the early 1960s. While the rest of Savile Row adhered to three-button coats, Sir Hardy blithely pushed the look to four buttons; having won that campaign, he's come out for five buttons, which appalls his Row neighbors but has designer Paul Smith following suit. Not many grown-ups can be observed yet wearing Sir Hardy's four-button coats with gillie collars, but his alma mater, Brentwood, has just provided him with a school full of young, somewhat reluctant customers, whose uniform Sir Hardy has redesigned, in charcoal gray, to sport four buttons. "My mum says that the four buttons are a bit weird," observes one fourth-former.

The first uniform Amies designed was actually his own, in the Second World War. His German, along with good French, had landed him in the nascent intelligence corps, for which no uniform had yet been designed. Amies's was based on the guards' uniform, "which I think is the smartest of the uniforms," he recalls. "It's still khaki, but it's rather more lovat green than yellow. So I had my suit made in guards' green." Amies wore it as his formal uniform throughout the war, not only in England but in Brussels, where he helped send Resistance parachutists behind enemy lines.

Amies admits to having had a "soft war" while the parachutists whose jumps he coordinated fell so often into enemy hands. As the suburbs give way to undulating fields and stone cottages, he talks admiringly of his friend Bunny Roger, who displayed great courage at Anzio. A British dandy, Roger designed extravagant clothes lined in fur and ran a showroom of his own within Amies's shop in the early 70s. He is still a brave fellow, Amies adds. "A couple of years ago I was at a party in Chelsea on Guy Fawkes Day, when we have fireworks. Up went a rocket, and down—into a tin of other fireworks. Everyone else—a bunch of queens—all went screaming indoors and hid behind the sofa. Bunny walked straight over and picked up the rocket and threw it off so it would explode in the air."

Yet the war made Amies a lieutenant colonel, and its wreckage enabled him to take over the damaged and abandoned Savile Row town house where, with £10,000 scraped up from family and friends, he began his business. Almost immediately, he became one of the Big 10, a postwar consortium of London's best clothes-makers, which included Edward Molyneux, Norman Hartnell, Victor Stiebel, Ronald Paterson, and Digby Morton. Today, he's the only one left.

Amies's village of Langford lies just within Oxfordshire, where the countryside begins to look like country and the farms like farms, despite the omnipresent crisscrossing utility lines. Since its founding in Anglo-Saxon times, the village has kept a population of about 300; its center is a narrow, winding lane bordered by houses of Cotswold stone. Some 25 years ago, Amies bought an 1840 schoolhouse here. Now he has also converted a stone barn into a guesthouse in another part of the village; behind it is the tennis court, which he can no longer use.

"Would you not like a short drink?" Sir Hardy inquires as he shows a visitor around the barn. At not quite noon he makes a Bloody Mary for himself—"lots of ice, you see"—and leads a tour. The double-height living room has a portrait over the fireplace that looks like a proper English ancestor— "I have no idea whose"—and a wall lined with bound volumes of Punch going back to 1841, and Country Life. Lining the tennis court outside are fine Victorian roses, leading to more roses in a small formal garden. At the garden's far end, Sir Hardy points out a house in the distance, on the far bank of the Thames. There, he explains, lives Lord Faringdon, the merchant banker whose wife is a customer, and who has agreed to become chairman of the trust. "And I'm going to become president, which means fuck-all," Sir Hardy says, though for a moment his bonhomie slips a bit. It is a step toward retirement, he admits. "But not completely."

Across the lane in the main house, Sir Hardy talks of his passion for needlepoint—the quite beautiful chair seats and a long upholstered footstool attest to his skills—and for the larger garden of roses, clematis, dianthus, and lavender that bloom where a schoolyard once lay. His sister, Rosemary, herself an active gardener at 80, appears for lunch. Afterward, over a plate of Stilton—"You don't know the proper way to cut it, do you? Here, let me"—Sir Hardy is asked one of those questions that people ask of octogenarians: whether the world is better or worse since he began.

"Oh, I couldn't possibly say," he says. "I suppose it's rather awful. But I have to say to myself that I'm very lucky to be where I am even if it is awful now. To have not been lucky in the days when it was very grand, I would have been nobody. I wouldn't have been unhappy because I wouldn't have known I was nobody. Nobody's ever known that they're nobody.

"I've thought of my epitaph," he adds in the garden. "Would you like to hear it? 'He was a court dressmaker, and an elitist with a sense of humor.' "

A large stone, it's observed, will be needed for that.

"Yes," he says. "Quite."

"He's a social snob, a garden snob, and a nine snob. It's part of his charm."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now