Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

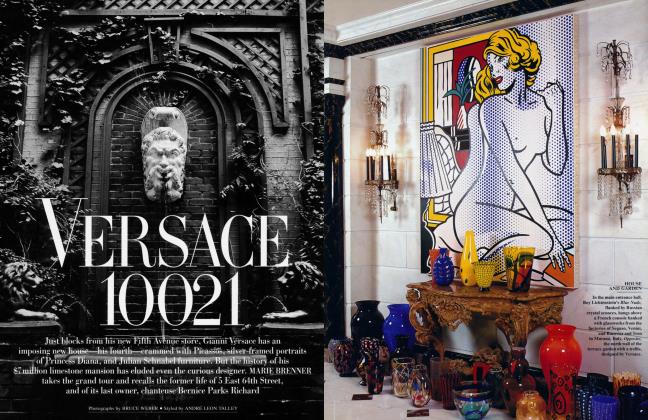

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowEMPIRE OF THE SONS

With the mysterious suicide of Amschel Rothschild in his marble bathroom at Paris's Bristol Hotel last summer, Europe's most prominent family lost the best hope of a new generation. Surveying the remaining Rothschild powers— from the flamboyant Jacob to the playboy Elie to the remote Evelyn—SALLY BEDELL SMITH discovers a dynasty in search of a leader

BEDELL SMITH

"I don't think anyone knew Amschel particularly well," said a cousin. "You wouldn't want to play poker with him"

On a cool and cloudy morning last July, a crowd of mourners gathered in a modest red-brick prayer hall called the Lodge at the edge of the Liberal Jewish cemetery in Willesden, North London. Beneath the vaulted ceiling stood two pedestals supporting large baskets of lilacs, lilies, roses, delphiniums, and lavender. Between the floral arrangements rested an oak casket marked with a small engraved brass plaque. Only 100 people could be seated in the seven rows of wooden benches, so hundreds of others spilled out onto the asphalt driveway, where a line of limousines waited behind a Rolls-Royce Phantom V hearse. As the service was relayed through loudspeakers, each mourner held a pamphlet on ecru paper containing Psalms in English and Hebrew. Printed on the cover was "Amschel Mayor James Rothschild, 18th April 1955— 8th July 1996."

Among the mourners were prominent bankers and executives, Treasury Chief Secretary William Waldegrave, television personality Anna Ford, former Rolling Stone Bill Wyman, and three generations of Rothschilds—34 in all, according to the count of Lionel de Rothschild, one of Amschel's cousins. Rabbi Julia Neuberger, a friend of the family's, sketched "Ammi's" character in a brief but eloquent eulogy. Although "he had compartments to his life," it was centered on his family and what it meant to be a Rothschild. "You were the focus of his life," Neuberger said to Amschel's widow, 38-year-old Anita, and his children: Kate, 13, Alice, 12, and James, 11.

He was a respected "City figure," Neuberger said, adding that he was a man of "immense loyalty," who "loved country life" and "was a most devoted friend." He was known, she said, for his "elegance, his charm . . . and his delight in complicated, and silly, jokes." He was devoted to Jewish causes and Israel through Hanadiv, the Rothschild-family foundation with $1 billion in charitable assets and more in real estate, and had a passion for history, auto racing, gardening, archaeology, and—in a touch of eccentricity so characteristic of his family—restoring old outhouses. Only once did she refer to the "appalling news" of Amschel's death the previous week, noting that his wife had borne the loss with dignity.

After more prayers, the casket was wheeled to a nearby grave. During the reading of the Kaddish, the Jewish prayer for the dead, Anita clutched the hand of one of her daughters and kept her composure. At the conclusion of the service, the rabbi invited family and friends to pay their respects by throwing soil on the casket after it had been lowered into the ground.

The leaders of Europe's most prominent family for almost two centuries filed past one by one: the two French patriarchs, 87-year-old Baron Guy de Rothschild and 79-year-old Baron Elie de Rothschild, and the two heads of the English branch, Jacob Rothschild, the 60-year-old fourth baron known as Lord Rothschild, and his cousin Sir Evelyn de Rothschild, 65. Slightly less senior were the three men who had taken over the Rothschild businesses in France from their elders: David, 54, Eric, 56, and Edouard, 39, who are all barons. The only important Rothschild missing was 70-year-old Edmond, a multibillionaire baron thought to be the richest of them all, who had not made the trip from his castle in Switzerland.

Along the path to the grave site were bouquets from friends and family to "dear Ammi." One, however, struck an oddly formal note. It was from Jean-Louis Souman, operations manager of the Bristol Hotel in Paris, who offered "sincere condolences and all our sympathy." It was an abrupt reminder of the mysterious circumstances of Amschel Rothschild's death in a marble bathroom at the luxurious Bristol. He had been found hanged from a towel rack by the seven-foot belt from a white terry-cloth robe monogrammed with the hotel's heraldic symbol.

At age 41, Amschel Rothschild had been carefully positioned as the next head of N. M. Rothschild & Sons, Ltd., the family's flagship bank in London, a 192-year-old institution steeped in tradition, the last significant private English merchant bank to be controlled by one family. He had been chosen at least in part because he was the only member of his generation—the sixth in the dynastywilling and able to become the bank's steward on the retirement of Evelyn, the demanding and energetic controlling shareholder. Amschel's generation, said his aunt Miriam Rothschild, "is rather sparse, because they are all younger. Sometimes generations get out of gear." Or, as a former director of the bank succinctly put it a few weeks after the funeral, "They are now short a Rothschild. Know any good ones?" By creating a leadership vacuum, Amschel's passing provoked a crisis for the English branch of the Rothschild family, which also carried implications for their French cousins. The death, first described as a heart attack and then disclosed to be an apparent suicide, also opened up the notably secretive family to the kind of scrutiny it usually manages to avoid.

The Rothschilds are neither the oldest nor the behest of the prominent European families, but surely they carry the most magical name, one that conjures up power, influence, and enormous wealth. The founder of the dynasty, Mayer Amschel, grew up during the 18th century in the overcrowded Jewish ghetto of Frankfurt, Germany. His name had been adapted from a red

shield—a rotes Schild— on the family's house.

Starting out as a trader in coins and fine objects, he established himself as a trustworthy investor and custodian for the wealth of German princes. In the early 19th century his five sons fanned out to build financial empires in London, Paris, Vienna, and Naples, as well as Frankfurt.

Over the years, the Rothschilds controlled vast fortunes, served as advisers and confidants to kings and prime ministers, financed Wellington's defeat of Napoleon at Waterloo, engineered the British government's purchase of a controlling interest in the Suez Canal, developed railroads in Europe, underwrote diamond mines in South Africa, financed cotton exports from America to Europe before the Civil War, suffered persecution by the Nazis, and survived French president Francois Mitterrand's Socialist nationalization during the 1980s.

In reward for their services, the Rothschilds were made Austrian barons in 1822; the French branch had already added the aristocratic "de" to their name when the family was ennobled six years earlier. Their coat of arms showed a hand holding five arrows, representing Mayer's five sons. After much reluctance, Queen Victoria finally gave the family its first English barony in 1885, which made Nathaniel Rothschild the first Jew to sit in the House of Lords. His father, Lionel, had been the first of his faith elected to Parliament.

As their riches increased, the Rothschilds built more than 60 elaborate palaces throughout England and the Continent. Their mania for collecting great paintings and priceless objects, along with their penchant for over-the-top luxury, became known as the "style Rothschild." When Wilhelm I of Prussia first saw Ferrieres, James's palace in the French countryside, he exclaimed, "Kings couldn't afford this. It could belong only to a Rothschild." At Henri's mansion at 33 Rue du Faubourg St.-Honore in Paris, the doors were "big enough to admit four tall giraffes, walking abreast," wrote the late Baron Philippe de Rothschild.

There is, fittingly enough, a breed of African giraffe known as Rothschild, as well as several varieties of Rothschild wine, including Lafite and Mouton, not to mention Rothschild hospitals, parks, museums, and housing projects representing the family's strong charitable impulse. Two movies have depicted the family's history: The House of Rothschild, produced by Darryl Zanuck in 1934, in which George Arliss played both Mayer Amschel and his son Nathan, founder of the British bank, and Die Rothschilds, a creepy, anti-Semitic production made in Germany in 1940 by Nazi propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels.

As one former bank director put it, They are now short a Rothschild. Know any good ones?

Numerous books have chronicled the family, ineluding memoirs by Guy and Philippe, who owned Chateau Mouton. A translator of English poetry, Philippe wrote in proud detail about his scandalous love life: "I was a tremendous success . . . leaping from bed to bed like a mountain goat. ... I was always convinced [my father] had won his spurs riding my grandmother's chambermaids. No, mine were ancient titles, fashionable beauties, stars of stage and screen, salon queens and one mutinous lesbian, only one." The memoir was published in 1984 in England but never in France, where the private lives of the wealthy are protected by strict laws.

Philippe's confession was a notable exception to the family's closely guarded privacy. Yet the Rothschilds are intensely conscious of their public image. In 1994, 90 family members gathered at the grave of Mayer Amschel in Frankfurt to commemorate his 250th birthday and to launch an exhibition of Rothschild art and memorabilia in the Jewish Museum, formerly a Rothschild palace. Accompanying the exhibition were an illustrated catalogue and a 400-page book of scholarly essays with such lofty titles as "The Rothschilds in Literature" and "Lord Rothschild and His Poor Brethren— East European Jews in London 1880-1906." Even now, a massive authorized history of the family is being written by Niall Ferguson, a young Oxford don. Amschel had been responsible for supervising the project, and only weeks before his death had met with the author to offer a detailed critique and ideas for future chapters.

"No Rothschild women and no in-laws. That's in case anyone marries a duffer and they lose the lot."

As other leading European families withered, the Rothschilds maintained a remarkable cohesion, even though offspring dispersed as far as California. The third and fourth generations intermarried extensively, but more crucial was a strict patrilineal structure set down by Mayer Amschel in his will. Only sons could own and run the family banks. While this consigned the Rothschild women to secondary status, it protected the family from interloping husbands. At the same time, the system carried a high cost: two of the family lines—in Naples and Frankfurt—virtually disappeared, and the family had to shut down those banks when there were no male heirs.

Still, the discipline of the family has ensured a remarkable vitality. "If you are a Rothschild, you are supposed to be sharp in finance, high-profile in the Jewish community, active in charities, very intellectual, and in the arts," said one family member. "There really is a big burden."

The Rothschilds have managed to produce generation after generation of brilliant bankers as well as talented scholars and amusing dilettantes. Alfred, a younger brother of the first English Baron Rothschild, built a French-style chateau called Halton, where he entertained his weekend guests by dressing as a ringmaster and performing with his trained animals. Arthur, one of his French cousins, lived on Rue du Faubourg St.-Honore and compulsively collected neckwear, which he changed three times a day. Walter, the second Lord Rothschild, assembled a natural-history museum on his estate, Tring Park, and created a respected system of zoological classification. He also trained three zebras to pull him around London in his carriage.

Rothschild women became collectors, academics, artists, and musicians. The most conspicuous and celebrated in modern times, a member of the fifth generation, is 88year-old Miriam, who has spent much of her life continuing the obsession of her father, Charles, cataloguing hundreds of species of fleas. Miriam's sister Kathleen Annie Pannonica was one of the first women in England to get a pilot's license. She later settled in New York, where she became a patron of jazz musicians, including Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, Miles Davis, and Thelonious Monk.

In the current middle-aged generation, Amschel's sister Emma graduated from Oxford, wrote an acclaimed book about the auto industry, was named a fellow at King's College, Cambridge, and is now a visiting scholar at Harvard. His other sister, Victoria, has been a lecturer at Queen Mary College, London. A cousin, Charlotte de Rothschild, is a classically trained soprano.

The Rothschilds have not been immune to scandal and misfortune. Walter Rothschild was tormented by a mistress who blackmailed him for four decades. There have been a handful of suicides as well. Oscar, one of the Austrian branch, fell in love with the daughter of a boardinghouse owner during a visit to Chicago. When his father said he couldn't marry someone so common, Oscar shot himself. Following numerous bouts of depression, Charles Rothschild, Amschel's grandfather, cut his throat after he contracted encephalitis.

Even in the recent past, such tragedies could be kept safely out of the press. Not so today, despite the family's best efforts. The door into the private lives of the Rothschilds opened quite literally shortly after 6:30 P.M. on July 8 in the Bristol. Naima Debbouza, a Portuguese chambermaid, knocked at Room 402, and Amschel Rothschild answered the door. "He received me oddly," Debbouza said in a written statement read at the inquest in London. "He took the box containing the washing out of my hands very aggressively and banged his door like someone annoyed, even disturbed."

Wilhelm I of Prussia said of Ferrières, "Kings couldn't afford this. It could belong only to a Rothschild."

"A Jew under Pétain, a pariah under Mitterrand— for me it's enough," Guy wrote in Le Monde.

Amschel had come to Paris to chair a meeting in the offices of the Rothschild family's Paris bank on the Avenue Matignon, just around the corner from the Bristol. The meeting had ended at five, and Amschel had arrived back at the Bristol an hour later. Sometime between 6:45 and 7, he called his wife's sister Miranda. According to a friend, he betrayed no worry or upset in the conversation, which concerned Miranda's personal life. "The conversation was perfectly normal," a court officer said at the inquest.

About 7:30, Debbouza returned to Room 402, and when her knock went unanswered, she entered the room to deliver fresh towels and turn down the king-size bed. At first she saw nothing amiss in the $900-a-night "deluxe double" with its Persian carpet and gleaming bronze chandelier. "There was a light in the bathroom," she testified, "and through the halfopen door I saw his feet, as though he was on his knees." According to a Parisian source familiar with the official police report, Amschel was naked under his bathrobe, and had slipped onto the floor after hanging himself from the towel rail. Debbouza ran to get help, but, as she later said, "he was already dead. His eyes were wideopen." Hanging himself could not have been easy for a man six feet one. The top of the towel rail was only five feet from the floor, although it was possible to kneel on the marble surface enclosing the bathtub and then drop the nearly two feet to the floor. The hotel management summoned a doctor, the police, an ambulance, and Amschel's cousin David. There was no suicide note or evidence of foul play. The conclusion, according to the police report: suicide by strangulation.

Where the story of the heart attack was conceived is a matter of speculation. After the discovery of the body, according to an informed Paris source, the family "called directly to the top of the government in France. They wanted no publicity, and the police report was sent immediately to the minister of the interior." "It was stupidity," said Nicholas de Rothschild, a cousin of Amschel's. "They did it to give themselves two minutes of breathing space, a damage-limitation exercise. ... It was going to get out; enough people knew about it."

Some press reports tried to explain Amschel's death by portraying his meeting at the bank as a failure, but those knowledgeable about the business said it had gone well. At the inquest, Peter Troughton, Amschel's deputy at the bank, testified that no problems or pressure had surfaced that day, and that there had been nothing unusual in Amschel's demeanor. "The great mystery of the suicide," said a friend of Amschel's, "is how successful the meeting was." The deeper problem, however, was that the profits from Amschel's business of "asset management"—managing the investments of wealthy individuals and large institutional clients such as pension funds—had been, in the words of one former Rothschild-bank executive, "slipping and sliding" even as its importance for the bank's future was growing.

Amschel Rothschild had joined N. M. Rothschild in 1987, at age 32. The youngest child of Victor Rothschild, the third Lord Rothschild, and his second wife, Teresa "Tess" Mayor, Amschel had grown up in Cambridge under the shadow of a father famous for his arrogance and rudeness. Victor Rothschild was one of England's celebrated polymaths—brilliant scientist, wartime countersabotage expert, collector of rare books and 18thcentury silver, single-digit-handicap golf player, cricket player, and government gadfly. Although his political sympathies leaned left, he headed a highprofile think tank during the government of Conservative prime minister Edward Heath. Late in his life, Victor Rothschild was accused of being the "fifth man" in the spy ring of Anthony Blunt, Guy Burgess, Kim Philby, and Donald Maclean, friends from his Cambridge University days who had passed classified information to the Soviet Union. He professed his innocence, and the government found that the charges were without basis.

After graduating from the Leys school in Cambridge, Amschel earned a degree at the City University of London. He was circulation manager for the admired New Review magazine in the 70s, before settling into his family's farm in Suffolk, where he manufactured apple juice. In his spare time, he played cricket and won auto-racing competitions. In 1981 he married Anita Guinness of the banking family, whom he had met while she was making salads at London's fashionable Club Zanzibar.

At the urging of his father, Amschel left his country-squire idyll for a life of London banking, to be groomed by his cousin Evelyn. The only other hope in his generation had been his cousin Lionel, whose father, Edmund, had been the bank's caretaker from the early 1960s until 1974. But in a complicated maneuver to avoid crippling estate taxes that would be due upon his death, Evelyn's father, Anthony, who ran the bank during the war, managed with the agreement of Victor and his cousins to reorganize the ownership structure. This resulted in a shift of control to Anthony and his "junior" side.

Lionel's brother, Nicholas, declined to enter the family business, because he concluded that there was "no incentive, no control of the shares." After running a video-production company, he moved to his family's estate at Exbury in 1990 to oversee the gardens and agricultural projects. Lionel tried his hand at banking after attending INSEAD, a top business school in France. But he too bailed out, splitting his time between Exbury and London, because, according to Nicholas, banking "didn't suit him. ... If you worked for Evelyn, you were under constant pressure." Lionel, whose wife, Louise Williams, is a violist who has recorded with the Chilingirian String Quartet, devotes himself to his children, photography, writing and editing books, and keeping the Rothschild family tree up-to-date.

That left only Amschel. Many have assumed that his father forced him into the bank as a kind of indentured servant to his powerful cousin Evelyn. But someone who knew all three men well observed, "I think Victor and Amschel both understood that Evelyn had the ability. Victor may have said, 'Your best interest is to ride with Evelyn.'" Amschel moved quickly up the ladder at the Rothschild bank after a brief apprenticeship as a silver trader, asset manager, and assistant to Evelyn. In 1990, Evelyn appointed Amschel as chief executive of Rothschild Asset Management (R.A.M.) in London, an important but faltering arm of the bank, and then to the chairman's job in 1993.

At the time, R.A.M. in London was one of eight such asset-management enterprises owned by the Rothschild bank around the world. A director who was there in the mid-80s recalled that the London operation was making $10 million a year, but after the departure of top executive Nicolas McAndrew the business began to sag. By the early 90s it had become, according to another former bank director, a "dull local business. ... In a good year we made a million; in a bad year, half a million." For Amschel, the challenge of turning the business around was explained by a former Rothschildbank executive: "The Rothschild name can collect money from all over the world. Rich people figure that it is a good bet to let Rothschild manage their money, but it hasn't been a success, and I know this worried Amschel."

"Chateau Clarke was a dirt patch. But he marketed the hell out of it, and it did very well."

The biggest player in the asset-management game, the Boston-based Fidelity Investments, manages $450 billion. R.A.M. London manages $18 billion. To bring Rothschild's asset management out of the doldrums and into the bigger leagues, Amschel wanted to consolidate all the R.A.M. operations around the world into one unified group managing $28 billion. Once the business became global, Amschel reasoned, R.A.M. could enlarge its roster of clients and increase its profits from management fees. It took two years of meetings and memos before Evelyn approved the plan in 1995.

Amschel also secured the cooperation of his cousins running the French Rothschild bank, who were partners with the English branch of the family in assetmanagement ventures in New York and Zurich. Evelyn set up a Dutch holding company to run the new operation, appointed Amschel chairman, made his French cousin David de Rothschild chairman of the supervisory board, and hired a new managing director, Peter Troughton. The meeting in Paris on July 8 was to set the strategy for the consolidated group.

Following Amschel's death, he was described in the press as a "reluctant banker" who longed for country life, a weak and timorous character who didn't seem tough enough for the business world. His appearance reinforced that impression. He was tall and thin, and his face had a haunted, languorous look: sculpted lips, heavylidded eyes, bushy hair, and a striking widow's peak. His manner was subdued. "I don't think anyone knew him particularly well," said Nicholas de Rothschild. "You wouldn't want to play poker with him."

With a personal fortune estimated at $50 million, Amschel could have opted out at any time. But those who knew him in the bank testified to his dedication to his job. "He would get up at 6:30 each morning, day in and day out," said one of his former colleagues. "He worked hard, not just diligently but with tremendous energy." Evelyn would scream and yell at him, as one observer described it, "as though Amschel was sort of a boy at school and Evelyn was head of house."

At such times Amschel would "clam up, repeat himself, and stand his ground," said one colleague. The man who was "quite cool as an auto racer," according to his cousin Nicholas, could also be "steelynerved" in business. Amschel knew how to wear down Evelyn's opposition by writing one brief memo after another. For all the pressure and confrontations, Amschel remained loyal to his cousin and tried not to take his behavior personally. As his friend William Waldegrave observed in The Daily Telegraph, Amschel "inherited the calm and humour of his mother; his father's sense of duty to his great name."

Amschel was no business genius, but in Evelyn's estimation he was a "working Rothschild," as the family calls those who commit themselves to toiling every day for one of the family businesses. With the help of good managers, including his cousin David, Amschel could be counted on as a caretaker who would ensure that the bank would run properly and pass safely to Evelyn's two teenage sons, Anthony and David.

Evelyn de Rothschild is an imposing force in the banking world. "He has quite a novel mind," said a businessman who has known him for more than a decade. "His personality is difficult to read. Therefore he is interesting if not likable. You want to try and figure him out." Six feet four, snowy-haired, and stylish, he has a handsome, leonine face and bright-blue eyes. He glides through a room with the varnished aloofness of the wealthy aristocrat and "very much likes to be in command," said his friend David Metcalfe, director of Sedgwick Group Development, Ltd., a global insurance-brokerage firm. He lacks the prized British gift for sparkling repartee, so he is often described as charmless. He failed economics at Cambridge and has been pegged as intellectually dull.

"Evelyn is not warm," said columnist Taki Theodoracopulos, who has known him for three decades. "He is not the type to put his arm around you. He is an enigma. . . . People mistake his lack of warmth for mean-spiritedness." In conversation he can be preoccupied—usually with business—and he is a man of few words. "He is the only man who can explain any situation in four sentences," said his friend Nicholas Haslam, the interior designer. "He is very, very succinct. You don't want to bore him. He gets the point quickly."

Like most Rothschilds, Evelyn lives in enormous comfort and with great style— but more modestly than his wealth would allow. His creamy-white three-story home in London's Holland Park is not even the most imposing on the block. In addition to his family's 19th-century estate Ascott, he has a house in Barbados and an old farmhouse in the South of France, where he supports a local cricket team. He doesn't own a private jet, although, conceded one friend, "he did take 90 separate bags on the Concorde to Barbados once, but they were filled with household items."

Evelyn's wife, an American named Victoria Schott, is 18 years his junior. She graduated from Trinity College in Connecticut and attended the Columbia University Graduate School of Business. They were introduced by Marion Javits, the wife of New York senator Jacob Javits. Evelyn's first marriage, to fashion model Jeanette Bishop, had broken up in 1971 after five years, and he and Victoria were married in 1973. Their friends include David Frost, London club proprietor Mark Birley, and Sotheby's consultant Peter Blond.

The focus of Evelyn's life for the past two decades has been N. M. Rothschild & Sons, located at New Court, a building on St. Swithin's Lane, in London's financial district. Since 1919 the world price of gold has been fixed twice each weekday—at 10:30 A.M. and 3 P.M.at the N. M. Rothschild offices; traders gather in a room where they stay in constant telephone contact with their own banks and signal one another by raising small flags. But the main business has been investment banking, which has earned the bank fat fees for arranging mergers and acquisitions and helping to privatize government-owned businesses.

When Evelyn took over as chairman in 1976, "everyone was skeptical," said one of his cousins. Since then he has transformed the bank into a business generating some $40 million in annual profits in recent years. He has made shrewd investments, such as a 26 percent stake in 1986 in the securities firm Smith New Court, which he sold to Merrill Lynch nine years later for a profit of more than $150 million. Along the way he multiplied his own wealth to more than $1 billion. "Evelyn has overachieved," his cousin continued. "The bank really has done well in a very competitive environment under his hand. I don't think people expected him to do that well." Evelyn succeeded by putting in long hours and demanding the same dedication from those working for him. "The British bank is not a big powerhouse," said a man with close ties to the Rothschilds. "The real issue is what Evelyn did. He kept it a private bank."

Because he doesn't seem either brilliant or clever, Evelyn has been consistently underestimated. One former director at the bank calls him a "dyslexic genius." His close colleagues know that he keeps things brief for a reason. He can get tangled in his words, he reads with great effort, and "he can barely write a letter on his own," according to a former director at the bank. "He is self-conscious about it. He keeps a dictionary by his desk." His subordinates know how to boil down the complexities of deals into simple and clear terms in terse memos, of which he digests probably 100 a day. Yet when it comes to business transactions, he has a long attention span: he took three years traveling to China every few months to negotiate a recently announced joint venture with the second-largest bank there.

Top executives at N. M. Rothschild have often complained that Evelyn keeps them out of the loop and makes decisions on his own. He employs a cadre of former civil-service mandarins for general advice, and he pays lip service to running the business democratically. The trappings of a public company serve mainly to impose corporate discipline on his troops. His actions are those of a sole proprietor, with all the prerogatives of that position. "With Evelyn it's La banque, c'est moi," said his cousin Nicholas. "He is the epitome of the bank, which goes against modern thinking. Banks are large conglomerates of individuals." The Rothschild bank, he continued, "is very much a family house, with him singularly identified with it."

For all his success, Evelyn has been continually overshadowed by his more expansive cousin Jacob, whose brilliance, charm, and boldness caught the imagination of the British press and never lost their hold. Jacob has actively courted publicity, while Evelyn has seemed indifferent. "Evelyn doesn't want to be a larger-thanlife character," said his friend Sydney Gruson, a Rothschild executive in New York. While Jacob loves being the center of attention, Evelyn "is terrible with journalists who rabbit on and try to impress him," said a former director of his bank. "He has no patience for it. He has tremendous assurance about who he is. He has nothing to prove except to other Rothschilds."

Jacob was Amschel's half-brother, the older son of the overpowering Victor. Jacob's mother was Victor's first wife, the former Barbara Hutchinson, who came from a bookish Bloomsbury family. They had a bitter divorce, and Victor vented his anger on his firstborn son.

For that reason, among others, the fourth Lord Rothschild seems remarkably insecure and contradictory. Jacob is tall, though not so tall as Evelyn, or so handsome. He is highly intelligent, and regales his friends—especially Gianni Agnelli and the Duke of Beaufort, two men he reportedly talks to on the phone frequently—with amusing stories. "Jacob is the greatest gossip in the world," said Taki. He loves being interviewed, but he can be "almost gauche in social circles, because he feels ill at ease," in the words of one friend. "We are told he is shy, but it is hard to see it," said David Metcalfe. "For someone in the news as much as he is, if he is shy he must be in agony."

Defying the family pattern of Harrow and Cambridge, Jacob went to Eton and Oxford, where he distinguished himself with a first in history. In 1961 he married Serena Dunn, the wealthy daughter of multimillionaire Canadian stockbroker Sir Philip Dunn. Small, witty, and strongwilled, she preferred the horsey set to high society, although she could dance so effortlessly that Nicholas Haslam took to calling her Ginger. Jacob and Serena had three daughters and a son, and for years Serena spent much of her time in the country—at Stowell Park, their home in Wiltshire, and Eythrope, their home in Buckinghamshire—while Jacob entertained at dinner parties in their London house in Little Venice.

Jacob got a reputation for flirting with attractive young women, but what one European woman called his "crushes" never threatened the marriage. In recent years, Jacob and Serena have been spending more time together as their children have gone off on their own.

Jacob learned about the banking business at Morgan Stanley in New York as well as at several London firms. When he joined N. M. Rothschild in 1963, it was a sleepy family office collecting dividends. He opened up the bank's operations by starting a corporate-finance department, where he advised large firms on high-profile takeovers. Evelyn had also joined the bank in the early 60s, but he preferred to spend his time in charity work, breeding horses, and playing polo— he called his team the Centaurs—and he left his younger cousin alone.

In 1975, Victor stunned the banking world by coming into N. M. Rothschild as its chairman when his cousin Edmund retired. At age 43, Evelyn also began paying more careful attention to the business. Upon retiring in 1976, Victor gave his support for the chairman's job to Evelyn, not to his own son. Although Jacob had a minority share of the bank's ownership to Evelyn's much larger share, he was still deeply disappointed. The cousins reportedly exchanged no harsh words at the time, but relations between them were so strained, according to a former Rothschild executive, that "when Evelyn wanted to go to the loo he would use the ladies' because Jacob would be in the men's."

Jacob remained in the New Court offices running the Rothschild Investment Trust (R.I.T.), a pool of funds he had been overseeing since 1970 and had increased from $66 million to $231 million in five years. Among the businesses he invested in were the Savoy Hotel and Sotheby Parke Bernet. In 1980, Jacob and Evelyn had what Nicholas de Rothschild called a "red-blooded boardroom punch-up" after Jacob pressed too hard to transform the bank into a public company; "but that was that," he added.

In Jacob's view, N. M. Rothschild could thrive only by enlarging and bringing in other shareholders. But such a move would have diluted Evelyn's ownership and made Jacob more important. Without consulting Evelyn, Jacob had struck an agreement with New York financier Saul Steinberg for a 20 percent stake in R.I.T. Steinberg was particularly worrisome to the family, because he represented "fast money," according to one family member. "The bank belonged to Evelyn," said Nicholas de Rothschild. "He was going to win." Alarmed by Jacob's actions, Evelyn pushed him off the board and out of the company.

Eelyn allowed Jacob to take R.I.T. with him and set up his own business, but the enmity bgtween the two men continued. Using his own funds and money he raised, Jacob successfully bought and sold investments throughout the roaring 80s, although he failed in two big takeover attempts—Hambro Life and BAT Industries. After the Hambro reversal, he sold off many of R.I.T.'s holdings for a significant profit—a move he referred to as his "retreat from Moscow," according to Rothschild biographer Derek Wilson. Nevertheless, Jacob's fortune also grew to more than $1 billion. "Jacob was tremendously successful at deals, but not successful at building a business," said a former Rothschild director.

With 19 years between them, Jacob and Amschel maintained a good relationship, even though Amschel was treated far more kindly by their father. "There was too big an age difference for them to be competitive," said a man who was friendly with both. "Amschel was in awe of Jacob until he got into the business. Then Amschel was less in awe and had a more fraternal relationship with him."

Jacob's wide-ranging interests have attracted as much attention as his banking activities. For six years he served as one of the most successful chairmen of the National Gallery, raising millions of pounds, expanding its collections, and overseeing the design and building of the much-praised Sainsbury Wing. He spent $28.5 million to renovate Spencer House, the former London home of Princess Diana's family, financed an archaeological dig at the ruins of Butrint in Albania, and underwrote the renovation of a famous 19th-century Rothschild palace called Waddesdon Manor. In 1988 he inherited most of a $166 million estate from his cousin Dorothy "Dolly" de Rothschild, along with Waddesdon and its trove of paintings and other treasures. When Gianni Agnelli heard about the windfall, according to a mutual friend, he remarked, "Everyone is saying Jacob is such a good businessman, but he got money the way we all did. He inherited it."

In 1993, Jacob turned his investment funds over to be managed by others and largely withdrew from active business operations. Since then he has devoted himself to running the National Heritage Memorial Fund and the Heritage Lottery Fund, which together disburse grants from the national lottery to worthy projects that enrich the culture and preserve the history of the United Kingdom. "It's like being Mr. Medici and spending someone else's money," said a friend.

When Jacob and Evelyn are compared, Jacob invariably emerges as the Renaissance man, while Evelyn seems focused on banking. Within the family, however, Evelyn is highly regarded because he has excelled in the family business and negotiated financial relationships with the other branches. "Evelyn was able to manage the family, and that is not an insignificant thing," said a family member. One of Jacob's most noted traits is what has been called plutophilia—an excessive admiration for newly rich businessmen. "Jacob couldn't care less about the Duke of Buccleuch," said a friend, "but he would like to have dinner with Bill Gates. . . . While Jacob had fun with his business, he didn't accomplish in Rothschild terms. He didn't build a business."

By contrast, Jacob and Evelyn's French cousin David did surpass family expectations. He rebuilt the French enterprise after Socialist president Frangois Mitterrand took power in 1981 and nationalized French banking and other industries. Yet after heading his own Paris bank for more than a decade, David is still eclipsed by three surviving members of the older European generation: his father, Guy, and his cousins Elie and Edmond.

Guy epitomizes the soigne Continental Rothschild, a 19th-century figure of elegant bearing and temperament. He was raised in two of the most opulent Rothschild palaces—the chateau at Ferrieres and a house on the Rue St.-Florentin where Talleyrand had once lived, which is now the American Consulate. One of Guy's fondest memories was of a Yom Kippur eve when he and his father, Edouard, began their fast by strolling together to the synagogue wearing white ties, tails, and top hats.

Guy studied at the Sorbonne and was married at 28 to a young widow, Alix Schey von Koromla, from a venerable Hungarian Jewish family. During World War II they fled to New York, where David was born. According to Countess Marina Cicogna, whose mother was Alix's closest friend, Guy's wife was "a quiet, complicated, and not very young woman. She was always serious and intellectually oriented. She was good-looking but very sedate in a sophisticated, quiet way."

The match seemed to suit Guy, a phlegmatic sort whose life was "soft but a bit dull, and very comfortable," according to his friend Alexandre "Sandy" Bertrand, a former publisher of French Vogue. But Guy's complacency was shattered when at age 46 he met 28-year-old Marie-Helene van Zuylen de Nyevelt, who had recently ended her marriage to Count Frangois de Nicolay. "Guy was attracted by this unexpected and improbable girl," said Bertrand. "She was never very pretty, but had an extraordinary aura. She was light in a room, very vibrant, and she was a perfect blend of American and European cultures." Born in New York City, she was half Egyptian and half Dutch, and her grandmother had been a Rothschild who converted to Catholicism when she married outside the faith.

Guy's romance with Marie-Helene caused a scandal. He divorced the widely admired Alix and married Marie-Helene in February 1957; their only child, Edouard, was born in December of that year. Throughout the 60s and early 70s, Guy and Marie-Helene entertained extravagantly at Ferrieres and the Hotel Lambert, the Paris town house built by the architects of Versailles, which they bought in 1975. "I admired the guts with which the Hotel Lambert was run," said Nicholas Haslam. "She was unafraid of being a Rothschild."

As high society's "Queen of Paris," Marie-Helene surrounded herself with a court of men and women from whom she expected complete loyalty. "She really devoted herself to the game of society," said Marina Cicogna. "She loved being a star." Cecil Beaton called her "difficult but divine," and she thoroughly mesmerized and amused her husband. She agreed to raise their son, Edouard, in the Jewish faith, but she remained defiantly Catholic, often wearing a large cross around her neck. At midnight on Christmas Eve one year, recalled Sandy Bertrand, Marie-Helene summoned Edouard and his half-brother, Philippe, her child from the Nicolay marriage, and instructed them to sing a Christmas carol to Guy's mother. "The baroness was extremely dignified and listened to the children," recalled Bertrand. "Marie-Helene was doing that all the time to irritate Guy. He took it with extraordinary calm."

Guy was not considered a great success as a banker. He took over the family's Paris operation in 1945 and eventually transformed it into a commercial bank with fewer than two dozen branches in French cities. It may have been one of the largest private banks in France, but it was a modest operation compared with the powerful Rothschild bank of the 19th century. The bank rose in importance from 1969 to 1974, when Georges Pompidou, a former Rothschild-bank director and close friend of Guy's, served as president of France. But Banque Rothschild's profits dropped sharply in the late 70s, when it was hit by a slumping economy and institutional clients began to reduce the size of their deposits. At the same time, Guy and Marie-Helene trimmed their lifestyle by giving Ferrieres to the University of Paris and selling some of its contents. By 1981, according to Rothschild historian Herbert R. Lottman, the Paris bank was rumored to be in "virtual bankruptcy."

When Mitterrand announced his nationalization program, Guy angrily declared on the front page of Le Monde that he was decamping to New York, as he had during World War II. "A Jew under Petain, a pariah under Mitterrand—for me it's enough," he wrote. The government paid the Rothschild family handsomely for their bank—roughly $110 million at today's values. Many in the French business community have said that nationalization actually saved the French Rothschilds. Still, according to a former director of N. M. Rothschild, "the French lost their bank. It rankles them, even though they got paid off as individuals."

Guy returned to France in 1986, when the Socialists lost the legislative election and Prime Minister Jacques Chirac began undoing nationalization. After a long and crippling arthritic illness that kept her confined to her bed for several years, Marie-Helene died last May. Since then Guy has spent most of his time with his family, although he has lately become such a sought-after dinner guest that his friends have taken to calling him "le veuf d'or" (the golden widower).

Guy's cousin Elie has also settled into Ja more sedate existence, with some provocative complications. In contrast to Guy's calm gentility, Elie is famous for his noisy and prickly temperament, and his tendency to blurt out any vulgar thought that pops into his head. "I like to shock," he has reportedly said. "I say outrageous things. Sometimes I feel bad afterwards, sometimes I feel great." He once insulted the owner of the HautBrion vineyard at a party by calling her wine "pipi de chat," and startled another unwitting dinner partner by popping out his glass eye—he was blinded in one eye at age 50 during a polo match—when she complimented him on its rich blue color. Many find his behavior appalling, but, according to Luke Burnap, an American expatriate in Paris, "he is a most beguiling person if you can put up with it."

Elie was deeply marked by his harsh imprisonment during World War II, after he and his brother, Alain, both officers, were captured at the Belgian end of the Maginot Line. During his confinement he was married by proxy to his childhood sweetheart, Liliane Fould-Springer, whose French-Austrian family were wealthy Jewish industrialists. After the war they had three children, a son and two daughters, and lived in an enormous mansion across the street from the Elysee Palace.

Elie also supported a series of wellknown mistresses. The first, during the 1950s, was Pamela Churchill, the former daughter-in-law of Winston Churchill. After Pamela bolted to New York in 1959 to marry Broadway producer Leland Hayward, she was followed in Elie's affections by Frangoise de Langlade, an editor at French Vogue, who would later marry Oscar de la Renta. In recent years Elie has been linked to a Parisian antiques dealer. "I love to have a mistress for a long time," he told one of his friends. "He is so proud of himself," the friend recalled. "He said, 'In a way I am faithful. When a mistress pleased me, I was faithful to her.'"

Although aware of Elie's prominent affairs, Liliane never seriously considered divorce. Forty years later, when Pamela Churchill, now Harriman, was appointed as U.S. ambassador to France in 1993, Liliane cracked to a close friend, "That makes one embassy where I don't have to go!" She kept her word, turning her back on the parade of upper-crust Parisians feted at the embassy. The affair with Frangoise de Langlade caused a permanent rift between Liliane and Marie-Helene; it was during a weekend at Ferrieres that Elie and Frangoise began their romance, which Marie-Helene openly encouraged.

Liliane, who is short and stout, prevailed over all her husband's mistresses through the force of her personality, her scholarly accomplishments—she is a respected expert in 18th-century art—and her quick wit. Elie has admitted to friends that she is wealthier than he is, and he recognizes, said a prominent European aristocrat, that "she loves and has stood by him, and he knows he would be dismissed as a silly playboy without her." "Elie has called Liliane every day of his life," noted a man close to the family. Like so many marriages that weather infidelity, theirs has settled into a tight relationship in old age.

Élie's interest was not initially in banking, so in the postwar years he focused on the Lafite vineyard and ran a chain of family-owned restaurants and hotels called P.L.M. He succeeded at both, but during nationalization the government bought P.L.M. along with the bank. He retired from Lafite in 1975, and his nephew Eric took over. Subsequently, Elie became chairman of the Rothschild bank in Zurich, a thriving asset-management business owned by several branches of the family. In 1992, however, Elie was swept up in an embarrassing scandal when a bank official was charged with taking kickbacks on unauthorized loans. The official then countered that Elie had served as a front man to help Italian clients evade taxes and had collected millions of francs in fees—a charge that Elie categorically denied.

With the bank facing losses of more than $100 million, Evelyn took over as chairman and convened the family members who owned the Zurich bank: Elie and his son, Nathaniel, as well as Edmond, David, and Eric. All had to contribute enough money to cover the losses and save the Rothschild name. In one day they produced $100 million, about $50 million from Evelyn alone. Evelyn cleaned house and installed new management. He spent two years with regulators and successfully disentangled Elie from the serious allegations against him. Evelyn got "frightfully angry" with Elie, according to a former Rothschild-bank official, and their relationship suffered.

The second substantial contributor to the Zurich bailout was Edmond, a Frenchman who spends most of his time in Geneva. Although he holds stakes in several family enterprises besides the Zurich bank, including Chateau Lafite and the Rothschild bank in Paris, Edmond has followed an independent path, and his worth has been estimated at well over $1 billion.

A "stocky bustling man with crinkly, greying hair," according to Derek Wilson, Edmond bears little physical resemblance to the other Rothschilds. His down-toearth manner is also distinctly "un-Rothschildian." A friend of Elie and Liliane's recalled the deference Edmond showed them when he came to dinner in Paris: "He behaved like the poor cousin, not the powerful cousin."

After being dispossessed during World War II, Edmond's father, Maurice, eventually ended up in New York trading commodities. By the time he left the United States, he was worth more than $1 billion and was later further enriched by the wealth of three branches of the family in Italy, Germany, and France. He returned to Pregny, his chateau on Lake Geneva, where he worked in his bed with five telephones spread around him. Maurice was a flamboyant playboy who had divorced his wife, Noemie, shortly after the birth of Edmond in 1926.

Raised by his mother in Paris, Geneva, and Megeve, the French mountain village she turned into a ski resort, Edmond inherited his father's vast estate, including 10 houses, at age 31. He had studied at the University of Geneva and attended law school in Paris. "I had no financial education at all," he once said. Edmond worked briefly for a Rothschild subsidiary bank before setting up his own, rival banks in Paris and Geneva. He operated as a venture capitalist and, like his father, increased his fortune through shrewd investing. His most famous success was Club Mediterranee, and his least likely a vineyard at Listrac called Chateau Clarke. "He took a huge risk at Chateau Clarke, and everyone thought he was cuckoo," said a family member. "It was a dirt patch. . . . But he pumped in huge amounts of money and marketed the hell out of it, and it did very well."

Edmond's second wife, Nadine Lhopitalier, may be the most controversial of the Rothschild spouses. The daughter of a cotton-mill worker and an unknown father, Nadine grew up in poverty and worked on an assembly line and as a maid, an artist's model, a chorus girl, and a film actress who did stand-ins for stars in nude scenes. She and Edmond married when she was seven and a half months pregnant. After their son, Benjamin, was born in 1963, she converted to Judaism.

Her parties at Pregny and Megeve were every bit as lavish as MarieHelene's. One extravaganza in Megeve in the early 60s lasted 100 hours. In recent years Nadine has written self-help books instructing women about etiquette and entertaining. But most Rothschild wives and daughters could never fully accept her, with her unfortunate combination of lowborn origins and flashy style. "She is afraid of nothing," said a Parisian aristocrat. "She is the richest of them all, but she couldn't give a hoot if she sees them. She is a very strong character."

In 1992, Evelyn named Guy's son David de Rothschild deputy chairman of N. M. Rothschild in London. With Amschel's death, David seems poised to replace Evelyn as chairman of the English bank, further solidifying the alliance between the British operation and a French bank one-tenth its size. In October, Evelyn combined N. M. Rothschild's international corporate-finance activities and named David chairman of the new subsidiary. In an interview with The New York Times, Evelyn said, "The first important strength of the family is unity." Still, neither man has confirmed that David will succeed Evelyn. "I do not know who Evelyn's successor will be," David told the Financial Times. "I hope he stays a long time, because he is doing a big job, and we do not need a power play."

Bankers who know the family well say David is unlikely to move to London to be full-time chairman. "I don't see him coming to England and running the business with Evelyn's family in voting control," said a former Rothschild executive in London.

David is usually described as hardworking and solid, a thoroughly dutiful Rothschild, much as Evelyn de Rothschild is characterized. "Like Evelyn, David is not particularly social. He doesn't live for parties," said Marina Cicogna. He is a goodlooking man of medium height who has grown portly in middle age. "He is not a brilliant conversationalist," said a woman who knows him socially. "He has conventional wisdom, not glittering expressions." His interests are confined to banking, his family, the Jewish community, and the environs of the Norman village of Reux, where he owns a house on 320 acres and was mayor of nearby Pont l'Eveque for 18 years. "David is well liked, streetsmart, and not a genius," said a former executive with the London Rothschild bank. "But he has beautiful manners, and that goes a long way."

After his parents' divorce, David lived in Reux with his mother and attended school in Deauville before graduating from the Lycee Carnot in Paris. On receiving an economics degree from the Institut d'Etudes Politiques, he eventually went to work for his father in Paris. After nationalization, David and his cousins Eric and Nathaniel created a new Rothschild merchant bank to advise major corporations on mergers and acquisitions. David modeled Rothschild et Cie on Lazard Freres, the most prestigious and influential such bank in Paris. To attract talented executives, he gave partners a share of the profits but kept ownership tightly within the family. In its more than 10 years of operating, Rothschild et Cie has advised on some major deals, including the $4.2 billion Philip Morris takeover of a Swiss candy-and-coffee manufacturer, Jacobs Suchard. Today the Rothschild bank remains a medium-size merchant bank, a distant second to Lazard.

David has a close working relationship with Evelyn based on mutual respect and loyalty. "It would have been easy for the English after French nationalization to forget about the French cousins, but they didn't," said one family member. "They found ways to work together." The English family's Swiss holding company has a minority interest in the French family's Paris-based investment bank, and Evelyn represents the English holding company's interest in the Paris bank. David and his cousin Eric sit on the English family's boards, including those of both N. M. Rothschild and R.A.M. The two family branches are partners in the Zurich and New York Rothschild banks as well as in a joint venture in Spain. When the French government chose the Paris Rothschild bank to privatize Renault, David brought in Evelyn's bank for its technical knowhow. In meetings, Evelyn is polite if guarded with David, treating him as a junior partner, not an employee. "Evelyn doesn't yell at the French," said one former Rothschild director. "He yells about them."

It would be difficult for David to give up his business in Paris to run the London bank. He is, as one English Rothschild banker observed, "obsessively French" and conscious of his important place in French business and the Jewish community. In 1983, after years of trying, David was finally admitted to the Jockey Club, described as "the most aristocratic and closed circle in France." "David as a Jew had to go through getting blackballed . . . and then being asked to come in," said a business associate. "He was fighting for all Jews, and he is a leader there."

Since boyhood David has been serious and responsible. In his 20s he had a romance with the model and actress Marisa Berenson, but he was uncomfortable with her glittering life. "That was as extravagant as he got with women," said one of his friends. David has been married since 1974 to Olimpia Aldobrandini, the daughter of an Italian prince; like MarieHelene, she chose to remain Catholic but agreed to bring up their son in the Jewish faith. For their engagement, Guy and Marie-Helene gave them a now legendary garden party at Ferrieres, where the chateau was adorned with 19th-centurystyle portraits of the couple three stories high and local citizens in 19th-century costume formed a tableau vivant on a nearby lake. David was 31, and Olimpia only 18. Two years later they had their first child, a daughter who developed serious medical problems. David and Olimpia then had two more children, a daughter and a son, but their first child's illness took a toll on the family.

Until then, David and Olimpia had been a golden couple in Paris; Olimpia frequented the fashion shows and was much admired for her understated beauty and style. But after her older daughter's health problems, Olimpia withdrew. "She became a different person," said Marina Cicogna. "She closed herself in . . . became more private and serious." David and Olimpia are seldom seen at big public events; they prefer to entertain at dinners in their Left Bank apartment.

"David has a family he couldn't leave," said one of his friends. "Olimpia you couldn't bring to England. She can't cope with a lot. She is an introvert." The best the London bank could expect from David would be a figurehead chairman, which still leaves open the question: Who would run the bank day to day?

David's cousin Eric, a son of Elie's brother, Alain, probably wouldn't fit the role, either. Since last July he has assumed the position of chairman of the new, worldwide R.A.M. operation. Surprisingly, he quickly became engaged in the asset-management business and the complexities of consolidating the eight smaller companies. But his first love remains Chateau Lafite. As its head for more than two decades, he brought new life to the distinguished vineyard and carved out a glamorous business for himself.

Of all the Rothschilds in his generation, Eric is singled out for his panache. Born like David in wartime Manhattan, Eric lived there until he was seven. He attended prep school in England, the Janson de Sailly high school in Paris, and majored in engineering at Zurich Polytechnical. He had a long period as a dashing playboy, hitting the nightclubs with other wealthy bachelors such as Venetian aristocrat Giovanni Volpi. When he was in his early 30s, he commissioned Andy Warhol to paint a full-length portrait of him in the nude. At age 43, Eric married a close friend of Olimpia's, a beauty named Maria-Beatrice Caracciolo di Forini, who comes from a family of wellborn Neapolitans.

Handsome, tall, and lean, Eric dresses in meticulously detailed bespoke clothes that "fall on him as if they just belong there," said one friend. "He has a fabulous slouch." When he entertains at Lafite, Eric often appears in a black velvet cutaway waistcoat with silver filigree buttons. Beatrice, who works in her own studio as a sculptor, is equally stylish; she was one of the first Parisians to wear John Galliano's avant-garde designs.

Eric and Beatrice live in a house that his father built at the back of the garden behind the grand Rothschild mansion on the Avenue de Marigny. In the late 1970s, Alain sold the mansion to the French government. Now guests of the president stay there during state visits. Alain's widow, Mary, lives on the second floor of the new three-story house, with her son and his family on the ground floor.

Eric and his wife live like haute bohemians, entertaining an eclectic crowd of social figures and artists with what a friend calls "effortless luxury." Their living room is filled with paintings by Balthus, Rembrandt, and Zurbaran as well as Oceanic and African art; their garage is famous for its polished concrete floor and a set of Marilyn Monroe silkscreens by Andy Warhol. After dinner, they often invite guests to have coffee in their bedroom, furnished with sofas, ottomans, and a state bed that belonged to Madame de Maintenon.

They unapologetically enjoy the Rothschild life, but Beatrice seems disinclined to be the next "Queen of Paris." "Beatrice is not into the grand Marie-Helene trip," said a friend. Like Eric's mother, Beatrice converted to Judaism, and she raises money for her favorite causes, most recently refugees in Bosnia.

Eric ardently promotes Lafite in Europe and the United States. When he gives a lecture on wines at Harvard Business School, "everyone is riveted," said one of his cousins. "He is great, great fun. Whether it's in French, English, or German, he is always playing with words." He is not known for immersing himself in the details of the business, but he has hired well and expanded into vineyards in the Napa Valley, Portugal, and Chile. Although Eric's work with Chateau Lafite is outside the bank, he is considered within the family to be a "working Rothschild."

The least likely among the French Rothschilds to take an active role in the English bank is Edouard, David's half-brother. He is a partner in the French bank, where he works on mergers and acquisitions. In his looks and his temperament, he resembles Marie-Helene more than his sedate father. "He is a big guy, tall, very handsome in a pirate way, dashing with a great aquiline nose, bright eyes, and a ready swagger," said Philippe Berend, a Parisian businessman. Like his mother, Edouard has a strong personality—too strong, some business associates and social friends say.

After receiving his M.B.A. at New York University, he married a Parisian named Mathilde Abdy, who had been the wife of English aristocrat Valentine Abdy. Marie-Helene disapproved of the match, so Edouard and his wife escaped to New York, where he worked in investment banking. They divorced after several years, and he is now married to Ariel le Malard, the first Rothschild wife to work in the banking business, for Lazard no less. She advises governments, mostly in the Third World and Eastern Europe, which doesn't put her in direct competition with her husband.

Edouard has an aggressive manner in business which colleagues at the bank find off-putting. Early in 1996 he tried to hire N. M. Rothschild's chief of capital markets, Tony Alt, which understandably irritated the executives in the English bank. Even Eric was moved to say of Edouard, "If you close the door, he comes in through the window." Both Edouard and his wife are ambitious enough to be a factor in the Rothschild family, but most likely only in France.

Other European Rothschild men either don't qualify for banking leadership or have taken themselves out of the running. Eric's brother, Robert, who is 49, lives quietly in New York, where he has invested in theater productions. MarieHelene's 41-year-old son, Philippe de Nicolay, works for the French bank, where he is regarded as a skilled salesman for the asset-management division. Although Guy welcomed him into the family and the business, Philippe lacks the essential name, and his mother raised him as a Catholic.

Elie's 50-year-old son, Nathaniel, received an M.B.A. from Harvard Business School and annoyed his French cousins with a know-it-all attitude. After initially working with them in the new Rothschild bank, he broke away, first to join Jacob in London, then to set up his own small investment-management business in New York. Married to the daughter of Israeli admiral Mordecai Limon, he keeps a low profile.

Edmond's only child, Benjamin, 33, studied computer science and communications in California and worked for a time in his father's bank. But in recent years he has moved away from the family business. He will inherit his father's fortune, but Edmond's Geneva bank may eventually be folded into the Zurich bank, owned by the French and British branches.

Now it is in the next generation that the family trolls for prospects. So far, only Jacob's son Nathaniel—known as Nat—seems to fit the profile of the "working Rothschild." Twenty-five years old and Oxford-educated, the future fifth Lord Rothschild is vice president of Atticus Capital, Inc., a hedge fund in New York City, and is considered a very bright and intense businessman. "Nat may be a force, because he is obsessed by the business and doing well," said a friend of Jacob's. "His father wants to talk about art, and Nat wants to talk about bond yields." Still, as a former N. M. Rothschild executive pointed out, "I don't know whether Jacob's son would work for the man who fought with his father for 15 years." Perhaps a more troubling sign was Nat's arrest on drunken-driving charges four years ago; he explained his behavior by revealing that he was suffering from "severe depression," for which he was receiving treatment.

Executives at the bank believe that Evelyn de Rothschild will remain chairman as long as necessary to enable his two sons to come in. Significantly, he is already starting to bring them along. When he traveled to China last August, he took his younger son, David, with him to observe how he completed an important transaction for the bank. Yet the real abilities of his boys may not begin to emerge for 5 or even 10 years.

The Rothschilds' adaptability has been one of their strengths, but it is debatable whether such a fiercely male-dominated family could cede control in the next century to a qualified woman. "There's the rule," Edmund de Rothschild said emphatically four years ago. "No Rothschild women and no in-laws. That's in case anyone marries a duffer and they lose the lot. That's definite. No exceptions." One obstacle for Rothschild women has been shedding their family identity when they marry. But if they were to keep the Rothschild name, the problem might well diminish. Philippine, the daughter of Philippe, married an actor named Jacques Sereys. But as the successful proprietor of Chateau Mouton in Bordeaux, she has used the Rothschild name.

Evelyn's oldest child, as yet unmarried, is 22-year-old Jessica, who is said to be bright. "Would Evelyn bring along his daughter the way he would a son?" mused a man who has known him for many years. "I have always been surprised that these people are immensely logical. But whether that would extend to passing control to a woman, I don't know."

Two months after Amschel Rothschild's death, R.A.M. revealed that in the fiscal year ended the previous March, losses had climbed to $9 million from $700,000 the previous year. At a time when the American stock market was booming, half of those 1995-96 losses had been from trading, the rest from the costs of modernizing and reorganizing the R.A.M. businesses. "It is disgraceful for any assetmanagement business to lose that amount of money," remarked one top London banker. "They should be making $15 million in profits." Given the magnitude of the loss, Amschel may have been more burdened than anyone suspected. Granted, he had been deliberately spending to expand the business, and since last March the operation has moved into the black.

Still, clients had been lost, fees were down, and investments under Rothschild management had clearly not performed. In a business where perception is crucial in buttressing investor confidence, the announcement of such losses could prove very damaging. Moreover, in their uncompromising self-judgment, the Rothschilds put the highest premium on success in running the family business. In that sense, Amschel may have suffered deeply from seeming to have let down his family.

Because there was no suicide note, Amschel Rothschild's death will remain the subject of competing theories. Besides his business pressures, Amschel was struggling with some personal problems. Friends say that his 15-year marriage to Anita was troubled, and that they had been quarreling. Amschel's mother had died in May, and his grief had been compounded by a sensational newspaper report that during World War II she had had a "sporadic affair" with the infamous spy Anthony Blunt, who was homosexual. During the same period, a close friend, Simon Weinstock, had died of cancer. "Was Amschel depressed? Certainly. Worried? Certainly. Sad? Certainly. Suicidal? No," said one of his close friends.

Amschel seemed to have more reasons to live than to die. He was intensely devoted to his children and talked about them constantly. He was a more familiar presence at his son's boarding school than other fathers, according to one parent. He and young James had been planning a big cricket match with a rival team for the weekend following the fateful Paris business trip.

Two weeks after the initial reports, the Sunday Express printed a story suggesting that French authorities suspected Amschel's death may have been accidental. "It is odd that he was naked, unless he decided on the spur of the moment," said a police source quoted by the paper. "But suicide on impulse in this way is very rare indeed." The implication was that his death might have come from autoerotic practices involving asphyxiation. A lawyer for his family insisted that he was fully clothed—which contradicted the police report.

During the inquest, coroner Dr. Paul Knapman seemed to address those suspicions when he said, "There are no bizarre features which are sometimes associated with male hanging." He concluded that the death was a suicide "based on the evidence that is available." Anita emerged as the most forceful advocate of the suicide explanation, telling the hearing in a statement that her husband "had depressive tendencies. We do not know the reason for this, but certain family antecedents predisposed him to this act."

Others in the family fastened on a theory that Amschel must have had, in his aunt Miriam's words, "a sudden chemical surge, like a burst blood vessel," which prompted him to take his life impulsively. To some, Amschel's rude behavior to the chambermaid was the tip-off. "He was meticulous about how he treated servants," said a friend of Amschel's. "The man described was not the man I knew." The Reverend Chad Varah, a suicide expert whose Samaritans organization had recently attracted Amschel as a fundraiser, explained that he may have had "endogenous depression generated from chemical changes within the brain. ... At any age it can suddenly strike. ... If a suicide is planned, the person uses a method appropriate to his or her class or background, such as an expensive Purdey or Holland & Holland shotgun. . . . They do not choose the belt of a dressing gown at a hotel. That seems like a sudden impulse, to seize an object near to hand."

For all the sadness and puzzlement, Amschel's death for the Rothschilds came down to "the king is dead, long live the king." Amschel was gone, and now they had a dynastic problem to solve. The Rothschilds have done as much as any family to sustain their wealth and influence, and their success has been marked by discipline and deep familial feelings. The tenacity of their Jewish identity has only intensified the strength. "As long as they maintain that identity," said one family member, "there is a certain drive to prove something. . . . Other families have no motivation . . . but if you look at the Rothschilds, everyone has some interest, and it has to do with a family that stays together."

But even if those traits endure, the power of the Rothschilds is likely to diminish. "In the 19th century the family made a startling amount of money," said Nicholas de Rothschild. "They grasped the wheel of industrialization and rode it like crazy. That fortune is already attenuated. . . . Once it is gone, it is gone. The opportunities to remake that kind of money are limited. None of us is Bill Gates. He has done it in this century." In his view, "the aura continues to radiate . . . but it is like the aftershocks of an earthquake. The earthquake is over, and all you get are echoes. That is all it is now—the echoes."

The gathering at Amschel's funeral showed the remarkable loyalty that the Rothschilds have toward one another despite differences in personal chemistry and philosophies of business. "If Mayer Amschel were to come back," said one family member, "he would look at the men and women and feel content. There is still a strong family feeling. The Rothschilds keep track. It may be a third cousin, but it's still a cousin, and Mayer Amschel would say that is not so bad."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now