Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowWIRED AT HEART

The New Establishment

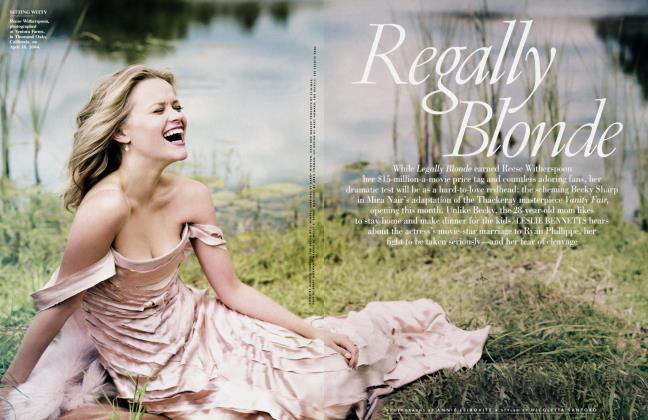

Esther Dyson's high-technology conference, PC Forum, has drawn everyone from Bill Gates to Michael Crichton and Michael Douglas. Her new book earned an advance of more than $1 million. And her opinion can make or break new high-tech ventures. Why is this tiny, disheveled intellectual the most powerful woman in Silicon Valley?

LESLIE BENNETTS

Every spring Esther Dyson's annual conference, PC Forum, draws hundreds of cyber-stars to some luxurious resort where information-technology billionaires mingle with baby moguls, a healthy smattering of investment bankers, and others hoping to cultivate high-level associations at poolside.

One regular presence is Esther's father, the eminent physicist Freeman Dyson, who once startled participants with an odd question. "He was going around asking people, 'Who is my daughter?' " recalled Mark Stahlman, the president of New Media Associates. That might seem a silly thing to ask about an internationally renowned high-tech guru—"the most powerful woman in the Net-erati," according to The New York Times.

In December, the Silicon Valley monthly Upside ranked Dyson No. 12 in its "Elite 100" list. "La Dyson is the highest-ranking member of the Upside Elite whose stature is based entirely on her ability to influence others with her ideas rather than control companies or huge amounts of capital," explained the magazine. Dyson was ahead of IBM chief Louis Gerstner (No. 14), Microsoft co-founder Paul Allen (No. 21), and Time Warner chairman Gerald Levin (No. 25)—and only one notch below Rupert Murdoch (No. 11). The magazine added, "Dyson has defied the traditionally short pundit's life span with more than two decades of savvy technology analysis."

Dyson's foresight is also the reason 600 people compete ferociously for the honor of spending $3,300 to attend PC Forum, which was held in Tucson this year. "A friend called up wanting me to help someone get in, and I swaggered and said, 'Sure—I'm a good friend of Esther's,"' reports Michael Kinsley, the editor of Slate, Microsoft's on-line magazine. "I was shocked that it would be necessary to use a connection for the privilege of paying thousands of dollars to go to this conference, but I was even more shocked when —lo and behold—I couldn't do it. It's like Studio 54: Esther's there with the rope, deciding who's going to get in."

In her rapidly changing world, Dyson knows virtually everyone who matters. "I know Esther because everybody knows Esther," says Steven Rattner, the deputy chief executive at Lazard Freres & Co. "Esther is six degrees of separation, except that it's about one and a half degrees. If the Pope could be a woman, she would be it. She embodies the virtual community everyone's talking about."

Esther Dyson began her ascent with Release 1.0, a newsletter she took over in 1982, renamed in 1983, and wrote singlehandedly for the next four years. "It is the computer industry's most intellectual newsletter," says author John Brockman in Digerati, a book about "the cyber elite." He adds: "Esther and Jerry Michalski [Dyson's managing editor, who now shares writing duties] are the peopie to read to find how people will use new technology and how companies can make a profit from it." Oddly, Release 1.0 is published in printed form rather than on-line. "The kind of in-depth analysis it provides doesn't lend itself to the Internet," explains Daphne Kis, the publisher. "The Internet is not yet a place where people spend their time on a hard read."

In whatever form, however, Esther's opinion matters. "She inspires awe and fear," attests Mike Kinsley.

"Esther is six degrees of separation, except it's about one and a half degrees. She embodies the virtual community."

For Dyson, the perennially profitable Release 1.0 and PC Forum were only the beginning; in what might laughingly be called her spare time, she has also become an expert on emerging technology in Eastern Europe; formed a venture-capital fund to invest in developing markets; established a second annual conference, the international High-Tech Forum, oriented toward Europe; advised Vice President Gore as a member of the U.S. National Information Infrastructure Advisory Council; and become chairman of the Electronic Frontier Foundation, a nonprofit organization started by Mitch Kapor, founder of Lotus, and former Grateful Dead lyricist John Perry Barlow to deal with civil liberties and ethics in cyberspace. (Along with other freespeech advocates, the E.F.F. fought a law later rejected by the Supreme Court which would have banned "indecent material" on the Internet.)

This fall Dyson will expand her influence with Release 2.0: A Design for Living in the Digital Age, which was signed up by Broadway Books last year for more than a million dollars. International rights went for what was rumored to be a similar figure.

The hoopla begins when Release 2.0 comes out this month. The unprecedented publication plan will include simultaneous hardcover editions in at least 15 other countries and a new Web site for readers around the world to discuss Dyson's views on such critical Internet issues as intellectual property, content control, privacy, anonymity, and security. Next spring, a revised trade paperback edition called Release 2.1 will incorporate reader feedback and Dyson's responses. By then the author, who is doing an eight-city book tour this fall, may be a familiar presence even to the cyber-impaired.

"This book is not a how-to manual," she claims. "It's a howto-think-about-it manual. I'm not about technology; I'm about the implications of technology. The Internet is very powerful. . . . It's your obligation as a citizen to know a little bit about what's going on in the world so you can make informed decisions. What I really want to be is a Dr. Spock for the Net: here's a lot of helpful advice, but in the end, use your own instincts."

As Queen of the Digerati, Dyson looks out of place. Elfin and disheveled, with short chlorine-scalded hair that sticks out in flyaway wisps (she swims laps for an hour every day), no makeup save the occasional trace of Chap Stick, and a sartorial style that runs to baggy jeans and promotional polo shirts from various conferences, she looks more like an impoverished student than a globetrotting venture capitalist who hobnobs with the titans of cyberspace.

Her appearance has remained essentially unchanged since her Radcliffe days. "She was so fragile and waiflike and soft-spoken, she was just not the kind of person you would expect to turn into a powerhouse business guru," recalls Kinsley, a fellow student at Harvard, where Dyson was referred to as Tiny Esther.

So what kind of person is she, really? Ask any number of prominent people and they will tell you how smart she is; many can even regale you with a description of her eccentricities, from her lifelong inability to keep her shoes on to her fanaticism about swimming. (She plans her travel schedule as well as her daily agenda around pool locations and hours, and friends jokingly say that her signature scent is Chlorine No. 5.)

But dig a little deeper and it seems that the Dyson everyone knows is somebody no one really knows. At 46, she has never been married, has no known romantic entanglements, no children or pets, and doesn't cultivate the intimate friendships that sustain many single people. She doesn't even have a telephone in her apartment. ("We never called her anyway," her famous father says.) Dyson's elusiveness has inspired some intriguing rumors—that she's gay, that she's a C.I.A. agent—all of which seem to be untrue.

But she remains a mystery, in some ways even to her own family. Talk to Esther's brother, the world's leading expert on the Aleut kayak, and at first he insists, "We're close." How often are they in touch? A bit sheepishly, George Dyson concedes, "I talk to her five minutes a year. I read about her in The Wall Street Journal1" If he wants to see her in person, he goes to PC Forum.

Verena Huber-Dyson, Esther's mother, says wistfully, "She's never been to my place. She is too busy, and she's just not interested. She is very hard-nosed and determined. But when I travel, I always let her know where I am, and chances are that once in a while we can spend 15 minutes at some airport lounge. She fits me in."

Esther says there's no one she talks to every day, and when I mention that to Freeman Dyson, he smiles. "She doesn't need that," he says condescendingly, as if such intimacy were unworthy of a superior being like Esther. "She never needed to come and talk about her problems, even when she was a child. She was very self-assured and able to cope, and she was a very private person. That, of course, is why we didn't know her very well. She was happy to be left alone. We hardly noticed her."

Famously driven, Esther maintains a prodigious array of contacts and obligations. Her book was due on June 30, but at the beginning of May she had little more than a chapter or two. But with a couple of million dollars at stake, Esther remained unflappable; she is the last person in the world who would ever succumb to such a human frailty as writer's block. "Esther knew exactly what she needed to do; she never doubted that it would all happen," says Janet Goldstein, her editor. With characteristic efficiency, Dyson set aside six or seven weeks to write, and turned in a completed manuscript of close to 100,000 words at five P.M. on June 30. Her publishers are planning a substantial first printing of 125,000 copies.

The day after her book deadline I called to catch up. "I can see you July 4," she said. I was not surprised; other people have resorted to picking up Esther at airports on Christmas Day in order to spend time with her. And so on Independence Day, while most of her peers were lounging on sunny beaches or wide green lawns, I met Esther at her office on Manhattan's lower Fifth Avenue. She had been there since rising at 5:30 A.M. in her one-bedroom apartment two blocks away. Having left the office only for an hour to swim laps, she could hardly wait to get on with her agenda. "I've got 1,500 E-mails to deal with," she said cheerfully. That is Esther's idea of a fun way to spend a holiday weekend: alone, working.

"Jerry describes Esther as being like a shark because she needs to be in motion. She needs constant stimulation and input or she doesn't breathe."

"What is it that drives her?" muses Freeman Dyson. "I don't know. That's why I was going around asking people, 'Who is my daughter?' "

The first time I met Esther, I was prepared for her coolly cerebral style, for her formidable intellect, even for her reserve. Although forewarned, I was not prepared for her office. Tornadoes ripping down Fifth Avenue could scarcely produce debris on this scale.

Immense piles of papers are heaped on every available surface; cascades of stuff overflow every shelf and drawer. Staggering quantities of junk are jumbled three feet deep on every square inch of floor: sweat clothes, stuffed animals, beat-up running shoes, discarded bras, magazines, skin creams and lotions, mountains of newspapers, a plastic container of mayonnaise, teetering stacks of books, tote bags with damp bathing suits trailing out of them, a half-eaten chocolate bar, Russian nesting dolls, unopened CDs, four-year-old paychecks.

Vaguely registering my amazement, as if with one tiny corner of her brain, Esther absentmindedly stuck out a bare foot and shoved a bedraggled pair of panty hose behind a pile of papers—a hilariously feeble gesture, considering the Augean-stable scale of what remained.

"At one point, the cancer began to ooze outside the door of her office," reports Bill Kutik, a Harvard friend who now shares space with Dyson's company, EDventure Holdings. "Finally we put white tape around a metastasized portion of the cancer and said, 'Esther, it cannot grow beyond the white tape.' It's clearly weird and sick. We're all sort of in awe about the horror of it."

The last time I was in Esther's office I remarked, "It hasn't changed a bit." Esther looked indignant. "I cleared a path over there," she protested, waving at the closet, which spills a permanent river of clothing into the room. It was true: there was now a tiny goat path leading to the cave.

Esther appears to live out of this closet. Our first conversation ended when she had to go to a meeting at IBM; a car was waiting downstairs. Still talking, she dug her way into the closet and rummaged about for some wearable clothes. Looking around, I realized that Esther, whom I had known for approximately two hours, had just let her clothes slide off her wispy little body. (She left them on the floor, where they will probably remain into the next millennium.) Esther continued talking about intellectual property as she wriggled into a pair of panty hose, put on a pink blouse and a burgundy suit, rolled up the waistband of her skirt ("I never got around to having it shortened"), and slipped into some sensible pumps. Ready for IBM.

Esther's explanation for her office is simple: "I don't have time to throw stuff away." Given the rigid self-discipline she exercises over every other aspect of her life, this may be the only way she ever abandons herself.

Dyson's fearsome productivity does have some disconcerting side effects. Although she is cordial, she usually seems distracted, as if her mind were simultaneously operating on other channels and your conversation with her has been deemed marginal in some private hierarchy. "When you come up to Esther, you're not sure she's paying a lot of attention to you," admits Stewart Alsop, a longtime acquaintance who runs Agenda, another computer-industry conference.

"You learn to have a purpose and get to the point if you want to talk to her," says Jerry Michalski.

Nor does she bother with social niceties. "Some people are used to a lot more pleasantries, and they can perceive her as being cold and aloof, but I perceive it as Esther being efficient," says Lori Fena, executive director of the Electronic Frontier Foundation. "She doesn't waste time on bullshit."

Nevertheless, intimidation is a Dyson specialty. Bill Kutik, who met Esther when she was a 16-year-old college freshman, vividly recalls their first conversation. "I took eight S.A.T.'s and Achievement Tests and I got six 800s," Esther announced, referring to an extraordinary number of perfect scores on the exams that weigh so heavily in college admissions.

The sneaking suspicion that Esther is smarter than you are may provide a crucial key to her success. This year's PC Forum featured a goodhumored Dyson roast where Kutik told the S.A.T. story. A couple of days later when Reed Hundt, the outgoing chairman of the Federal Communications Commission, got up to debate the logistics of providing Internet access to schools, he was still wrestling with Esther-inspired insecurities. "You have the six 800 test

"Esther never needed to talk," says her father. "That is why we didn't know her very well. We hardly noticed her."

scores, so I'm worried about saying no to you," he confessed.

Esther has spent decades honing that edge. "She has always been so competitive," says her mother, who is Swiss. "She always enjoyed being smart, and there was always a one-upsmanship that wasn't necessarily appreciated by the other kids. She won all the tests in school, and she always had straight A's. She likes to win."

That made life difficult for her younger brother. "It was an impossible handicap to follow Esther in school," George Dyson says. "She was not only stellar in her accomplishments but off the scale in her determination to be first."

Both George and his father have already published books this year, and George sees this as having prompted his sister's sudden interest in writing one.

"When I got a contract, she had to catch up," says George, who has broadened his scope from kayaks to Darwin Among the Machines: The Evolution of Global Intelligence.

Part of Esther's secret is an extraordinary ability to focus. "Esther works harder than anyone you'll ever meet," says Kutik. "She'll be reading something when she walks down the street. She doesn't waste two seconds."

But the usual measure of success doesn't seem to motivate her at all. "Esther is the only person I know who has gotten rich, relatively at least, while never caring for a second about money," says Kutik. "She doesn't give a rat's ass about making money. I really think that for her it's just a way of keeping score: How smart have I been in my bets?"

She certainly doesn't go in for conspicuous consumption; the single most expensive item she's ever bought is a Russian sculpture of a bird that cost $1,500. While other cyber-moguls collect planes and boats and all manner of high-tech toys, Esther not only doesn't own a car but also has never had a driver's license; she takes the subway. She doesn't buy designer clothes; she doesn't own houses or anything but her apartment, a tiny walk-up on East 12th Street where she's been living for 25 years. "It's the standard one-bedroom brownstone apartment you move into when you're 24 and leave when you're 32," Kutik reports. "Except that she never left. Esther just considers it a place to sleep."

Other than flying first-class, her sole concession to greater affluence has been to buy the apartment across the hall as a crash pad for out-of-towners, many from Eastern Europe. "I'm too cheap to put visitors up in a hotel," she explains.

Esther prefers to invest her money— not necessarily in those ventures that would reap the greatest profits, which she could easily have done, given her ground-floor role in the computer industry, but rather in enterprises she finds intellectually intriguing and useful. "Money enables me to invest in things I think should exist," she says.

'If I were running this company as a business, the job would be to maximize profits, but we have real social and political preferences that get played out," explains Daphne Kis, the vice president of EDventure Holdings ("Esther runs around the world and I run the company"). "Esther is interested in having fun and building an on-line community that's Pan-European. She is driven by wanting to make sure she's not bored. ... It is a source of great satisfaction to her to put people and resources together and influence the outcome."

And so Dyson zooms from one country to another, never stopping. The last time she took a vacation was almost 10 years ago, when she spent four days in Barbados; needless to say, it was someone else's idea, and she hasn't had a vacation since. "Other priorities," she says with a shrug.

Kis likes to quote Jerry Michalski on Dyson's essential nature: "Jerry describes Esther as being like a shark," Kis says, "because she needs to be in constant motion. If she stands still, that's when she doesn't live. She gets frustrated. She needs to be having that constant stimulation and input all the time or she doesn't breathe."

Esther's brother attributes much of her unrelenting drive to their father. "As children, you strive for approval from your parents, and if they make approval hard to get, you're going to strive harder," says George Dyson, who found his childhood so traumatic he moved to a British Columbia rain forest to live in a treehouse 95 feet off the ground, perched in a Douglas fir. "My father is a hard act to follow. When both your parents are remarkable academics—well, I think Esther went into money for a lot of the reasons I went into kayaks. We both picked something totally different from what our parents did."

The senior Dysons are definitely a little scary: Freeman, who switched from mathematics because physics was more challenging, is known as one of the principal architects of quantum electrodynamics; Verena is a mathematical logician. But Esther hasn't fallen all that far from the family tree. As John Brockman points out in Digerati, her parents' areas of expertise "represented the two fields whose intersection brought the computer revolution to life."

Freeman Dyson proves a tough judge of his daughter's achievements. "I'm always surprised that people pay so much for so little," he says brightly when I ask him about her monthly newsletter, which 1,800 people pay $695 a year to receive. "It's surprising how little illuminating stuff I've found in it."

Others disagree, citing her astute understanding of where the industry is headed. "Esther is very firmly focused on a point about five years out from any one time," says Stewart Alsop, who has published his own newsletter, P.C. Letter.

Although Bill Gates is no longer a regular, PC Forum also maintains great cachet among the software developers, Internet entrepreneurs, service providers, Wall Street analysts, investors, and venture capitalists who vie to attend. "I think it's very hard to leave this conference without $5,000 worth of value," comments Ann Winblad, a partner in Hummer Winblad Venture Partners, a venture-capital firm specializing in software companies (she is also known as Gates's former girlfriend).

"The first time I heard about the Internet was here," attests venture capitalist Henry Kressel, of E. M. Warburg, Pincus & Co. "Esther is always ahead of the pack."

Dyson prides herself on bringing together what she calls the "ante-establishment," or the top dogs of the future, and her instincts are renowned. "Esther's success rate in spotting entrepreneurs who really will be successful is very high," says David Braunschvig, a managing director of Lazard Freres.

Although Dyson's detractors carp about PC Forum's penchant for abstract intellectualism ("Boring and irrelevant," says one, who attends faithfully nevertheless), others find its speeches and panel discussions stimulating. "What makes Esther different from other people in the industry is that she works on multiple levels—on social issues, on relationships—it's not just about technology," said John Sculley, the chairman of Live Picture, who was chatting beside the pool with Steve Case, the chairman and C.E.O. of America Online. "It's the implications of what the technological changes mean, and how all the ground rules change because of what all these people are doing. Esther manages to see the whole mosaic."

"She's never been to my place. She's just not interested," says Dyson's mother. "Once in a while we can spend 15 minutes at some airport lounge."

Even at PC Forum, however, you will hear—from a respectful distance—the usual questions about Esther. "Does she have a life?" wonders one acquaintance.

Esther is known to have had at least a couple of relationships over the last three decades—one at Harvard with Timothy Crouse (who went on to write the seminal campaign book The Boys on the Bus) and one in the mid-1980s with Bill Ziff of the Ziff-Davis Publishing Co., which briefly employed Esther to head up an unsuccessful trade paper called Computer Industry Daily. Rumor has it that her interest in Russia developed when she became smitten with a Russian; the infatuation ended, but her passion for Eastern Europe remains. Indeed, Esther always seems to be most deeply engaged by ideas rather than people. According to her mother, this has been the case since she was a small child.

Huber-Dyson, who ran off with another mathematician when Esther was five and George was three, doesn't claim to understand what makes her daughter tick. "It's still a mystery to me too," she admits. "But it certainly started early. Esther as a little girl was exactly the way she is now. She's very reserved. She'll easily turn you off if you start getting too personal. ... If you want to tell her something about your own worries, she may or may not want to hear. She may be, deep down, just afraid of getting involved. It's actually sad. . . . Looking at what happened to me, she may have made a rational choice that she wasn't going to get into any of these muddles."

Although the breakup of her family was shocking— Huber-Dyson never told Esther and George that she was moving out—Esther responded with her usual detachment. The night Freeman tucked the children into bed and broke the news that their mother wouldn't be coming back, Esther replied calmly, "I don't see what you need a mother for after the milk stops."

Her father soon married the children's au pair, and they had four more daughters. Esther grew up in Princeton, where her father has been associated with the Institute for Advanced Study since the early 1950s. She is very fond of her father and stepmother, Imme, although she rarely sees them, but Esther has never forgiven her mother. "She has re-edited her life, and my mother's not in it," George Dyson says sadly.

Her mother adds regretfully: "Sometimes I have the impression Esther thinks her mom was a fool by trying to do too many things and not doing anything perfectly. I think she doesn't want to have personal involvements interfere with her career."

Esther may also have set the bar too high. "When she was little," her brother reports, "she said she could never marry someone unless they were smarter than she was and wealthier. When you're Esther, that limits the field."

Although Esther describes the process of writing her book in terms of being pregnant and delivering her creation, the real thing doesn't interest her. "The notion of having children was never appealing to me," she says. "I couldn't do this and have a family life. ... I believe in parents' being present for their children, and I didn't want to be a bad mother."

Esther gazes at me unflinchingly as her unspoken words—"like my mother" —hang in the air for a long moment. "Besides, I wanted to have my own identity," she adds briskly. "And I really like my life. I've never felt lonely on a Saturday night; I'd rather be alone than be bored. There seem to be a lot of people who are just desperate for companionship. I'm not."

Doesn't she ever feel something is missing? "She doesn't stop for long enough to ask that question, or for it to really get to her if she does," says Daphne Kis. "She's unlike any other woman I know."

Gender inevitably intrudes on speculation about Esther; if she were a man, would her to-the-exclusion-ofe very thing-else brand of workaholism seem so noteworthy? "The easiest way to understand Esther is to think of her as Ed Dyson and not make the assumptions we all make, in our deeply ingrained sexist way, about what are a woman's needs and what are a man's needs," says one longtime observer. "She is curiously undersocialized. Her own work life is so incredibly rich, complex, and overbooked that she doesn't have time or space for anything else, but that seems to be enough for her. Is she the warmest, sweetest person? She is not, but who could be when work is all that matters to you? I would guess Esther's vision of people is mostly their utility: how smart they are, how interesting they are. She cares more about a good idea than anything else."

And right now the idea is to spread the word about the Internet, its potential and its pitfalls. When I ask Dyson what her larger aim might be, she replies, "The goal is to help the industry to grow and to define itself, and to help the world be more efficient." She grins, her well-scrubbed face and Peter Pan haircut making her look more like an impish child than an empire builder. "It's all very grandiose."

Having finished her book, she headed off again—to London, to Santa Fe, to Aspen, to Moscow. Despite her jammed schedule, Dyson doesn't feel overburdened. "I feel lucky that I can do what I like," she says. "I have a job that is defined by me."

To her mother, watching from afar, tiny Esther still reminds her of the little girl she used to call Esty. "She has the concentration of a kid playing Monopoly," says Huber-Dyson. "She was so methodical she would drive us up the wall. She would say, 'Wait—I have to figure this out!' She doesn't want to be disturbed at her game. She's still playing."

And in the process, she is helping to shape a new world. "She thrives on the front edge of new technology, new issues, new markets," says Lori Fena. "She's out on the frontier where there are no trails."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now