Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowEditor's Letter

Under Siege

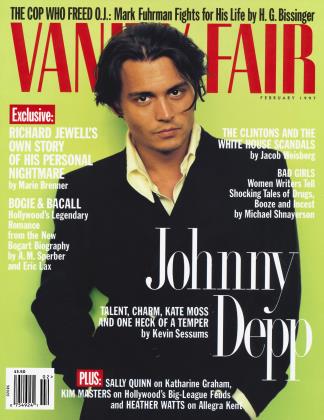

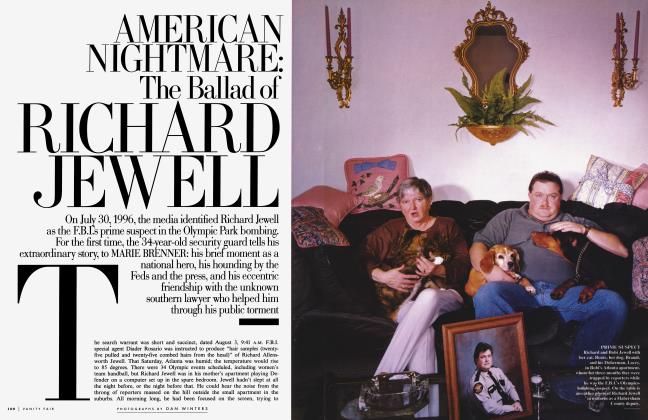

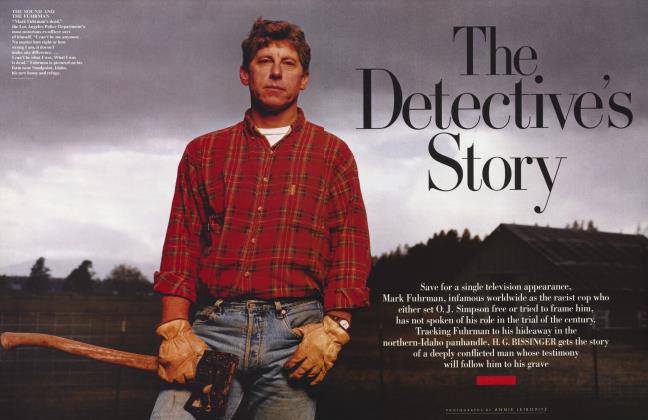

In this issue are two stunning examples of how the American media culture can pluck otherwise common men from obscurity, make their names and faces known around the world in a matter of hours, and turn once private, everyday lives completely upside down. Richard Jewell, for 88 days seen as the F.B.I.'s principal suspect in the Olympicsbombing case, and Mark Fuhrman, the L.A.RD. detective whose racist comments did more to free O. J. Simpson than any absence of evidence, have each experienced this profound circus nightmare.

Both men have remained largely silent regarding their roles in two of this decade's more closely watched stories. But they each speak out for the first time in print this month: Jewell to writer-at-large Marie Brenner, Fuhrman to contributing editor H. G. Bissinger.

With Richard Jewell, who was a hero one moment and a perceived monster the next, appearances can be deceptive. Overweight, the mustache, the gun thing, lives with his mother—who wouldn't jump to conclusions? Brenner agrees in part. "Like so many who watched the Olympics-bombing story on television," she says, "I got a picture of Jewell as a hapless dummy and a plodding misfit. Instead, I found a man who was very aware of the nuances of his situation, with a sophisticated knowledge of police work." Her article "American Nightmare: The Ballad of Richard Jewell," on page 100, is a sobering journey into what she calls "the dark side of law enforcement. Until the F.B.I. finds the bomber, it is Jewell's destiny to be viewed through the filter of being an F.B.I. suspect."

Bissinger has similar thoughts about Fuhrman. "I sensed that there was more to the man. And when I met him it was clear that he was not at all the stereotype that had been portrayed." Investigating further, Bissinger found that Fuhrman's L.A.P.D. colleagues, both white and black, also disagreed with the media stereotype. "The Detective's Story," on page 114, reveals a flawed, difficult, and complicated man whose life has held much tragedy. But, for all the parallels between Fuhrman and Jewell, there is a fundamental difference: Fuhrman's current tragedy is classical and largely self-inflicted; Jewell is living a Hitchcockian nightmare that, as Brenner points out, anyone might face. "What would you do," she asks, "if the F.B.I. showed up at your house and made you the prime suspect in a crime you hadn't committed?"

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now