Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

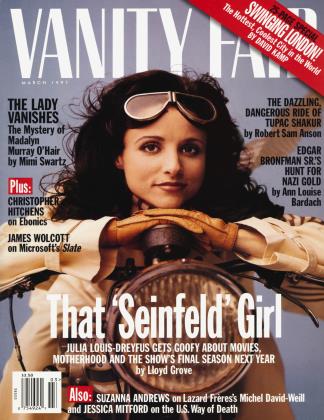

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowDEATH, INCORPORATED

Business

In 1963, the author's best-selling exposé The American Way of Death detailed the scandalous practices of America's funeral industry and sparked a reform movement. In a posthumously published update, she found that now huge conglomerates are squeezing the bereaved

JESSICA MITFORD

On September 18, 1996,The Wall Street Journalran an article on a recent development in the funeral industry: "Although more than 85% of the nation's 22,500 funeral homes are still independently owned, that percentage is shrinking rapidly as small chains and individual facilities are quietly bought by the likes of investor-owned chains such as ...Service Corp. International of Houston, which yesterday made a $2.8 billion offer to acquire Loewen Group Inc., the Canadian concern that ranks as its largest competitor. "

Four days later,The New York Timessaid of the proposed merger, "When Jessica Mitford skewered the death business years ago, could she have imagined a company like Service Corporation International?...But Ms. Mitford missed it; she died in July. " Jessica Mitford rarely missed anything. In the months before her death, she wrote the following article forVanity Fair.It will be part of her revised edition ofThe American Way of Death,which is now being prepared by Robert Treuhaft, her widower, Robert Gottlieb, her editor, and Karen Leonard, her longtime researcher.

Before The American Way of Death was published in August 1963, I wondered who would want to read a book about funeral reform. Unitarians, earnest consumer advocates, university eggheads, and the like? To my astonishment, the response was nothing short of thrilling. The book zoomed to No. 1 on the New York Times best-seller list, where it stayed for several months. CBS broadcast an hour-long documentary, The Great American Funeral, based on the book. Clergy of all faiths reinforced the major themes of The American Way of Death and denounced ostentatious, costly funerals as pagan.

Most gratifying of all was the response of the funeral industry. The trade journals reacted with furious invective, devoting reams to "the Mitford menace," "the Mitford war dance," "the Mitford missile."

I was aglow with pride (which, as we know, goeth before a fall), because so many of the reforms I proposed in the book seemed to be bearing fruit. The number of Americans choosing cremation-cheap, expeditious, and ecologically sound—soared from 3.71 percent to more than 21 percent. Most heartening of all, the Federal Trade Commission (F.T.C.) promulgated a "trade rule" which threatened to curb some of the funeral industry's more outrageous practices.

But today, 33 years on, there is little left to cheer about. The average undertaker's bill in 1961 was $708 for a casket and "services" exclusive of cemetery or crematorium charges. Today the average is $4,700. The industry has put its own spin on cremation, placing burdensome obstacles in the path of the family bent on a quick and simple send-off.

The F.T.C. has in important respects capitulated to industry lobbyists. The most devastating change is the unprecedented phenomenon of corporate takeovers of formerly independent funeral establishments, a development that is fast eradicating any perceived advantages to the hapless funeral purchaser.

I ime was when cremation was the bete noire of the funeral trade—the cheapest and usually the most private means of disposition. The trade did all it could to discourage the procedure, referring to cremation as "burn and scatter," or even "bake and shake." The National Funeral Directors Association (N.F.D.A.) advised stressing to potential customers the concept of "immediate disposal," implying that the Loved One's remains would be treated like so much garbage.

Slowly, over the years, the cruel realization dawned that cremation was not only here to stay but also increasingly the choice of the well-to-do and welleducated—those who could easily afford the finest offerings of the mortician. The industry made a responsive U-turn. The goal now is to steer survivors to purchase what undertakers are pleased to call a "traditional funeral," meaning a full-scale service with the embalmed and beautified corpse on display in a lavish casket, all to be consumed by flame, the ashes to be placed in a suitable costly urn.

As to the F.T.C., there was rejoicing in the ranks of consumers when it announced in 1975 its proposed trade rule on funeral practices. Its provisions would require:

1. That prices be itemized. Existing industry practice was to quote a package price based on the cost of a casket plus "our full range of services." Under the new rule, a price list had to be furnished, giving the cost of each "service"—embalming, transportation, use of mortuary chapel, counseling—which would enable the purchaser to choose or refuse any item.

The trade did all it could to discourage cremation, referring to it as "bake and shake."

2. That a price list be given to the customer.

3. That prices be quoted over the telephone.

4. That permission of next of kin be obtained for embalming.

5. That funeral directors be prohibited from misstating the law. Funeral directors were known, for example, to tell customers that embalming was required by law, which is generally not true in the United States. Likewise, there is no law requiring a coffin for cremation, or an outer container, called a vault in the trade, for ground burial.

The industry reacted with unusual ferocity, denouncing the proposed rule as Communistic and atheistic, and saying that it was tampering with the soul of America. The N.F.D.A. announced a "war chest" of $500,000 to fight the rule, and later raised the amount to $1 million. Thomas H. Clark, counsel for the N.F.D.A., was able to report successful lobbying efforts: "We got seventy-three Congressmen and thirteen Senators who signed resolutions condemning the F.T.C."

The rule was adopted by the F.T.C. in 1982, but the industry was given two years to come into compliance; nothing was enforced until 1984.

Consumer rejoicing was short-lived. The F.T.C.'s record for enforcement has been deplorable. Complaints by funeral purchasers against morticians in violation of the rule are routinely ignored. The total number, nationwide, of formal enforcement actions against funeral establishments in 11 years, from 1984 to 1995, was only 42.

The rule, designed at best merely to bring funeral-trade practices into conformity with general business ethics, has been watered down over the years to the point where today it is meaningless. Its key provisions have been gutted. Funeral directors are no longer required to tell the consumer who telephones that price information is available. They may lump together under a single, "nondeclinable" fee all unallocated services and staff time.

The crypts, stacked six-high, cost from $7,395 to $8,895—tl expensive ones "at heart level."

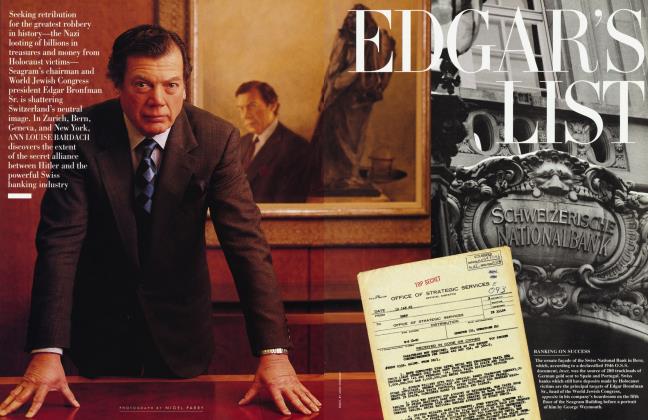

Enter the corporations that have recently penetrated the funeral scene: pioneers in the drive to upgrade and up-price cremation, and principal beneficiaries of the F.T.C.'s ignoble retreat. Of the three publicly traded major players—Service Corporation International (S.C.I.), the Loewen Group Inc., and Stewart Enterprises, Inc.—S.C.I. is the undisputed giant.

Its 1994 annual report to stockholders vibrates with pride of accomplishment: "Service Corporation International experienced the most dynamic year in its history in 1994, reaching new milestones in revenues and net incomes while establishing a solid presence in the European funeral industry." Revenues exceeded $1 billion for the first time. Holdings grew to include 1,471 funeral homes, 220 cemeteries, and 102 crematoriums. Its crowning achievement was the takeover of 15 percent of British funeral establishments, and within a year it would own 9 percent in the United States and 24 percent in Australia.

By mid-1995, S.C.I. had devoured yet another large U.S. company, Gibraltar Mausoleum, with its 23 funeral homes and 54 cemeteries, and had obtained its first foothold in Continental Europe with the acquisition of France's largest funeral chain, Pompes Funebres Generales, comprising 900 facilities in France and others in Switzerland, Italy, Belgium, the Czech Republic, and Singapore. S.C.I.'s revenues for 1995 exceeded $1.5 billion. By 1996, its pre-arranged-funeral revenue surpassed $370 million, and its pre-need cemetery sales came to an additional $251 million.

[In January of this year, S.C.I. dropped its bid to buy Loewen, which by then had risen to $3.2 billion. But had the merger occurred, the company would have owned 3,750 funeral homes and would have performed one of every seven American funerals.]

Given these outstanding accomplishments, much now depends on the level of performance of the Grim Reaper. Can he be counted on to do the job? Mortuary Management was gloomy on this score, noting that, due to recent medical advances in the treatment of cancer and heart disease, the death rate was bound to decline.

Not so the brokerage houses and investment analysts, who are showing much interest in the new conglomerates. Goldman Sachs, analyzing their prospects, predicts a rosy future:

Aggregate deaths have increased at roughly 1.1% on a compound basis since 1940. . . . Going forward, the continued aging of baby boomers, coupled with an increasing proportion of people over age 65, should keep aggregate deaths rising. . . . The aging of America should enable the deathcare industry to experience extremely stable demand in the future.

The Chicago Corporation is equally sanguine: "The addition of well-chosen death care stocks to an investment portfolio can increase the value of that portfolio nicely."

Of the 22,500 funeral homes in the United States, the vast majority are small operations doing somewhere between 50 and 150 funerals a year. Critics of the industry used to attribute high prices to this factor—they pointed out that the owner who performs one or two funerals a week must nevertheless maintain a full complement of embalmers, equipment, hearses, funeral cars, and sales personnel to serve these few customers. "It's full-time pay for part-time work," as one analyst put it.

S.C.I. entered this picture with the force of a hurricane, swept away the antiquated methods of the old-timers, and substituted "clustering," the latest in streamlined mass production. Borrowing from the successful techniques of McDonald's, where food preparation and distribution functions are centralized, S.C.I. first buys up a carefully chosen selection of funeral homes, cemeteries, flower shops, and crematoriums in a given metropolitan area.

The next step is to move the essential elements of the trade to a central depot. "Clustered" in this hive of activity are the hearses, limousines, utility cars, drivers, dispatchers, embalmers, and a spectrum of office workers from accountants to data processors, who are kept constantly busy serving the needs of a half-dozen erstwhile independent funeral homes, at a vast cash savings to management. Needless to say, the savings obtained via the cluster approach are not passed on to the consumer. S.C.I. prices have risen sharply—according to some estimates by at least 5 or 6 percent a year. In markets such as Houston, where S.C.I. with its 20 funeral and cemetery businesses has a predominant position (75 percent of the market), its prices, according to a recent survey, average 60 percent higher than those of independents in the area; in Washington, D.C., 40 percent higher. Prices of Loewen Group mortuaries tend to parallel those of S.C.I.

The funeral customer is totally unaware of clustering, because of the immensely successful S.C.I. policy of anonymity. In general, the plan is to acquire John Doe's Chapel of Eternal Rest and keep not only the name but also Doe himself as the salaried manager, thus ensuring continuity of community recognition and goodwill. Walking into the establishment, customers are greeted by Doe, who leads them through the casket-selection room and signs them up for the funeral. Little do they know that the Dear Departed will be whisked off for embalming elsewhere, only to reappear—looking 20 years younger, having been nicely made up and elegantly dressed—in Doe's "slumber room," where friends and family may gather to say their last farewells, for a price.

Customers taken through the casketselection room by Doe may think they are being shown some randomly placed caskets, but Doe is actually following a strategy carefully plotted by his employers. An S.C.I. directive to its Australian employees reads like a TV mini-series script, complete with stage directions:

As your arrangement comes to the casket selection stage, we would like you to use the following approach:

'Mr. and Mrs. -, I would now like to assist you in selecting a suitable coffin or casket for-."

ENTER SELECTION ROOM AND PROCEED TO STAND BEHIND THE CLASSIC ROYAL IN THE MIDDLE OF THE ROOM. GUIDE THE FAMILY TO STANDING IN FRONT OF THE CLASSIC.

"I would like to introduce you to our Classic Royal. This design is that of a European contemporary coffin. It is elegant [s/c] finished in Rose Mahogany gloss with fine line gold engraving on the sides. This unit combines expert craftsmanship with a fully satin lined interior. It is priced at $1595."

There are then presentations of the Classic Regal, priced at $1,995, and the White Pearl, priced at $995.

NOW PROCEED TO THE HANOVER IN YOUR RIGHT BACK CORNER AND STAND BESIDE IT.

There follows a glowing description of the Hanover, priced at $2,995. Doe or his counterpart then tells the family:

"I will be just over here (move to near the top of the stairs) if you have any questions."

The final stage direction:

ALLOW YOUR FAMILY AS MUCH TIME AS THEY NEED BUT ENSURE THAT YOU DO NOT LEAVE THEM IN THE ROOM UNLESS IT APPEARS THAT THEY WISH TO DISCUSS THEIR CHOICES PRIVATELY. READ THEIR BODY LANGUAGE.

The casket prices quoted for Australia may be increased by a factor of three or more for their equivalent in this country. Note the use of the word "coffin"—a definite no-no in the lexicon of the American funeral trade. But Down Under, the word "casket" may mean—as it does elsewhere in the English-speaking world except for the United States—a box for jewels and other valuables.

Tucked into S.C.I.'s 1995 annual report is a detachable card addressed "To our valued SCI shareholders: . . . directed toward the more personal side of funeral service." The message:

As an owner of shares in SCI, you are probably aware that the company's name does not appear on any of our funeral homes or cemeteries. If you, your family, or friends are ever in need of the services we provide, or would like to investigate the advantages of preplanning, the 800 number below has been enclosed to help you find the SCI firm most convenient to you.

The message has a socko ending: "Please accept our sincere apologies if this message reaches you at a time of loss."

The average undertaker's bill in 1961 was $708, exclusive of cemetery charges. Today it is $4,700.

I rang the number, 800-9-CARING, and obtained the names of S.C.I. mortuaries in a number of cities across the country. Eventually I got the price lists from a dozen or so. These are several pages long, covering the costs of a dizzying variety of "services" and merchandise-caskets, vaults, burial clothing. The accompanying explanatory text is virtually identical for all S.C.I. establishments. First comes the statement "The goods and services shown below are those we can provide to our customers. You may choose only the items you desire. However, any funeral arrangements you select will include a charge for our basic services and overhead."

The crunch is in that "however." It means that no matter whether or not you choose any of the listed services, you will have to pay for all of them. And here they are:

MINIMUM SERVICES OF THE FUNERAL DIRECTOR AND STAFF: This fee for our basic services and overhead will be added to the total cost of the funeral arrangements you select.

Personnel available 24 hours a day, 365 days a year to respond to initial call. [That is, somebody at the funeral home will answer the phone.]

Arrangement conference. [Mortuaryspeak for clinching the sale.]

Coordinating service plans with cemetery, crematory, and/or other parties involved in the final disposition of the deceased. [This would be akin to what your travel agent does when he or she reserves your flight, rental car, and hotel.]

Clerical assistance in the completion of various forms associated with a funeral. [These are forms needed to apply for money due from insurance policies, Social Security, the Veterans Administration, and trade-union death benefits.]

Securing and recording the death certificate and disposition permit. [The doctor or coroner supplies the death certificate, and any needed permits can usually be had from the local health department.]

Also covers overhead, such as facility maintenance, equipment and inventory costs, insurance and administrative expenses, and governmental compliance. [Curiouser and curiouser. The buyer is assessed for everything from upkeep of the parking lot to dusting the office furniture, and, under "governmental compliance," must pay for the funeral parlor to refrain from breaking the law.]

Aside from the fact that most of these "services" could be performed by the deceased's family and would take up at most only a couple of hours of funeral-home staff time, this is a prime example of the F.T.C.'s craven capitulation to powerful industry lobbyists. S.C.I. has here bundled together an allocation of its entire overhead, upkeep, and salaries into a nondeclinable fee.

orest Park Westheimer Funeral Home in Houston, Texas, where S.C.I.'s world headquarters are located, in 1995 charged $1,682 for "minimum services," which is about average for the 20 S.C.I.-owned funeral homes in that city. Forest Park also has a cemetery, a mausoleum, and a lawn crypt area. Thanks to Marcia Carter, a longtime resident of Houston who spent days unraveling Forest Park Westheimer prices, a fully developed picture emerged.

"If you choose not to be embalmed, then you have to be refrigerated, even if you have direct cremation."

Carter happens to be the owner of two F.P.W. crypts, bought by her parents in 1960 for $1,705.50. When her parents died, they were cremated elsewhere, and over the years Carter had made sporadic efforts to unload the crypts. F.P.W. declined to buy them back. "I was told they had very little value because they were in the 'old, outdoor' section of the mausoleum," she explained to me. "The desirable crypts are now in a new, air-conditioned section." Carter next proposed to donate the crypts to a local church or nursing home for use by a destitute family. "The cemetery told me that transfer of the crypts to 'unknown persons' was prohibited. They said the cemetery reserved the right to have the final say as to who would be buried there."

In my efforts to interview Robert Waltrip, the founder and C.E.O. of S.C.I., in Houston in the spring of 1995 for this article, I had had many superpolite telephone calls with Bill Barrett, head of S.C.I. corporate communications. Eventually I got a fax from Barrett: "I regret to report that Mr. Waltrip's travel and business commitments over the next couple of months are going to make it impossible to schedule time to visit with you." The reason became crystal-clear when somebody slipped me a copy of Inside SCI: A Publication for SCI Employees and Affiliates, containing an article by Barrett in which he warns his colleagues, "An interview with the media is serious business. The image and reputation of your business are at stake. If the preparation leads you to conclude it is not in your best interest to do the interview, don't."

I could see that my hopes of an interview were pretty unrealistic. But then, by a stroke of luck, I got in touch with the incomparable Molly Ivins, of whose journalism I have long been an avid fan. It turned out that she had been a friend since childhood of Marcia Carter's. Together we decided that I should metamorphose into Marcia's beloved old Aunt Jessie from England.

Aunt Jessie seemed like the perfect solution. Alone in the world, she would welcome the idea of Houston as a final

resting-place, close to her niece's family. Marcia phoned for an appointment, and together we repaired to F.P.W. on May 26, 1995.

A stylish young "pre-need counselor" named Sandy showed us around. Marcia said she was keen to see everything, since she might want to do some advance planning for her own family. Very sensible, Sandy said, and she should decide soon, for the prices of crypts would be going up on June 1. "You mean six days from now? That doesn't give us much time. And how much more would they cost?" Sandy said she didn't know; that would be up o the head office, which hadn't yet announced the new prices. But the prices of crypts normally double about every five years, she said.

Sandy showed us everything. As Aunt Jessie, I was especially interested in the crypts, so unlike the ones in Westminster Abbey. More like mini-mini highrise condos, I said. These coffin-size concrete boxes, stacked six-high, were variously priced from $7,395 to $8,895. Why the $1,500 difference, inasmuch as they appeared to be identical? The more expensive ones are at heart level, Sandy explained, adding, Oh, by the way, there's an opening-and-closing charge of $660 per vault.

dragging, in which she was shunted from executive to executive; eventually Pat Geary, then manager of Memorial Oaks, another S.C.I. mortuary-cemetery combination, rang back to say that there was no increase planned for the crypts, that Sandy had been mistaken.

The following day Marcia Carter phoned the S.C.I. headquarters to inquire about the June 1 price increases. There was a certain amount of foot-

For some days Marcia strove to sort out what the total cost would be for Forest Park's cheapest plan—First, if one of her crypts was used; second, for a "direct burial" or a "direct cremation," meaning no viewing of the body and no religious service.

"I must say, these people really don't like to talk prices!" she said. David Dettling, then funeral director at Forest Park, was less than forthcoming about "minimum services." "He could not, would not break it down," Marcia told me. "There's no avoiding that charge, even if we are able to perform most of the things enumerated ourselves."

Next on the price list: preparation of the body. Embalming, $425. Refrigeration, $425. "They get their $425 either way," said Marcia. "If you choose not to be embalmed, then you have to be refrigerated, even if you have direct cremation. They also told IRC that 201 unembalmed body can only be viewed by the legal next of kin, and then only for a few moments. This has to do with liability of the funeral home for 'bloodborne pathogens'!" (One of the more dazzling flights of fancy; as any pathologist will tell you, viewing a body poses no health hazards. Dead people don't breathe. The only serious health risk is during embalming, a procedure which extracts blood from the corpse and exposes anyone nearby to pathogens and toxic fluids.)

CONTINUED ON PAGE 131

CONTINUED FROM PAGE 120

After many phone discussions with various S.C.I. personnel, Marcia got some figures. First, direct cremation:

Minimum services for direct

cremation $1,252

Transportation of body from

place of death to funeral home 355 Refrigeration 425

Cardboard box 275

Crematory charge 475

Vehicle for picking up certificates 100 Total $2,882

Next, assuming that Aunt Jessie breathes her last in Houston and ends up in one of Marcia's crypts:

Minimum services $1,682

Transportation of body from

place of death to funeral home 355 Refrigeration/embalming 425

Minimum sealed gasket casket 2,598 Transferring body from

funeral home to crypt 275

Open/close crypt 660

Vehicle for picking up certificates 100 Total $6,095

[Opening/closing-crypt charges rise to $685 on Saturday before noon, $760 on Saturday afternoon, and $975 on holidays. Never on Sunday.]

"I asked why they charged $275 to take the body the 200 yards from the funeral home out to the crypt—that seemed exorbitant," said Marcia. "He said it's a fixed fee within a 50-mile radius. Even so close it's the same because of the 'cost of maintaining the vehicles, their insurance, and so forth.' Outrageous! Also, I asked why the minimumservice fee of $1,682 couldn't be discounted for immediate burial the same as it was for cremation, and he said they did that to make cremation a little cheaper than burial."

Those who are inclined to even a modicum of ceremony would have to add a few of the following items from the F.P.W. price list to the above rockbottom minimum:

Use of facilities and staff services

for visitation, per day $ 98

Funeral service in F.P.W. chapel 725 Staff and services in other facility 725 Use of chapel for memorial service

without remains present 725

Equipment and staff services for

service at graveside 515

Additional charge for use of

facilities/staff on Sunday or holiday 600

There is lots more—clothing, up to $192; flowers, up to $2,000—but why go on? Readers can check out the S.C.I. facilities in their own community by calling 800-9-CARING.

Where does all that money go? According to Graef S. Crystal, a corporate-compensation expert, S.C.I. is one of the 10 companies out of a total of 414 that he studied in 1995 whose directors and chief executives were most overpaid. The directors of S.C.I., he reckons, were overpaid by 95 percent, and C.E.O. Robert Waltrip, the founder and the brains behind the company, by 62 percent.

I asked Crystal how much the S.C.I. directors get. A total pay package, comprising annual retainer, meeting fees, stock options, pension benefits, and deferred compensation, of $102,000—maybe more, he said. "Fair pay, considering the size and performance of the company, would be $49,700." And the C.E.O.? "He gets a total value of $4,321,000. Using the same factors, a fair package would be $2,670,000."

The trade journals reacted to my book with furious invective, devoting reams to "the Mitford menace."

Heading the list of the high-priced S.C.I. directors is Anthony L. Coelho, chairman and C.E.O. of Coelho Associates, better known as Tony Coelho, former Democratic congressman from California. As chairman of the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee from 1981 through 1986, according to The Washington Post, Coelho, some say, "sold the party's soul in the process, by vastly expanding the contributions of business political action committees—and the expectations those contributors felt in return." In 1989, under a cloud of scandal, he resigned from the House of Representatives, relinquishing his powerful position as majority whip just one step ahead of Justice Department and House ethicscommittee inquiries involving his personal investments. In 1994, rehabilitated by the passage of time, he joined President Clinton's inner circle of advisers.

Like the Grim Reaper himself, Coelho is a bipartisan sort of fellow: "I have great friends on the Republican side," he told The Washington Post. "[Lobbyist] Jim Lake and I are as close as brothers!"

All of which bodes exceeding well for the future of S.C.I.'s global village of the dead.

Jessica Mitford died on July 23, 1996, at the age of 78. She had once suggested playfully that when she died she wanted a hearse pulled by a team of plumed horses, and her family and friends arranged the cortege down Embarcadero Street in San Francisco as part of her memorial service, which included a band playing ''When the Saints Go Marching In. "

'Decca, " as she was known, never was granted an interview by S.C.I., but she went as far as to fax the company a detailed list of questions in February. S.C.I. declined to respond to the questions, requesting instead that Mitford let the company review this article for accuracy before it was published. She declined, and made one last request, which was submitted to Robert Waltrip, chief executive of S.C.I., by Karen Leonard, Mitford's researcher: "Ms. Mitford feels that you should pay the bill [for her burial]. In her own words, 'After all, look at all the fame I've brought them!'

"Enclosed you will find the statement of funeral goods and services selected. I'm sure you will appreciate her frugality.

I think you will particularly like the price of $15.45 for the cremation container. While looking through S.C.I.'s price lists while we were in Texas, we couldn't find a cremation container for under a couple of hundred! Think of what it would have cost you if she had dropped in Houston!"

The total cost of Jessica Mitford's funeral, arranged by Pacific Interment Service of San Francisco, was $562.31, "sea scattering included. "

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now