Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowWHITING FOR GODARD

James Wolcott

Pauline Kael and her fellow film critics once wielded the power of their passions to make and break careers. Today’s reviewers shuffle into screening rooms to whine about the death of the movies. Where did the love go?

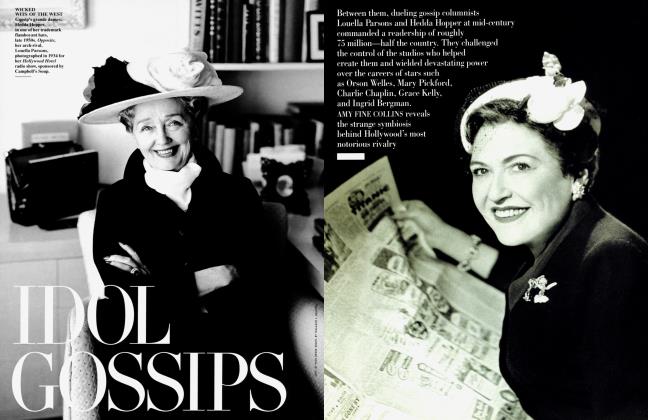

Last year I briefly pinch-hit for a movie critic on paternity leave. It wasn’t my first tour of duty: I had reviewed movies for eight years at Texas Monthly, and during the 70s and 80s attended countless other screenings as a friend of Pauline Kael’s. Those were the days. Film critics had the oral swagger of gunslingers. Quick on the draw and easy to rile, they had the power to kill individual films and kneecap entire careers. David Lean, the lordly director of Lawrence of Arabia and The Bridge on the River Kwai, was so demoralized after being verbally smacked around during a meeting with members of the National Society of Film Critics in a private room at the Algonquin Hotel in 1970 (the critics wanted to know, as the meeting’s chairman, Time’s Richard Schickel, expressed it, “how someone who made Brief Encounter could make a piece of bullshit like Ryan’s Daughter”) that he retreated like a wounded animal, and didn’t make another film for 14 years. Amongst themselves, critics engaged in personal feuds and turf wars that struck bystanders, in the words of Wilfrid Sheed, “like a cross between a thirteenth-century theological squabble and a fixed wrestling match.” Once a year, like a groundhog, The Village Voice’s Andrew Sarris would poke his head out of a pile of Cahiers du Cinemas (the auteurist bible) and grouch at anyone doubting the divinity of, oh, Otto Preminger. New York’s John Simon cast aspersions in print and spittle in person; the mere mention of Barbra Streisand sent him orbital. On talk shows, Rex Reed and Judith Crist traded low blows.

Splinters of paranoia sharpened the air. It was the Watergate period of The Conversation and The Parallax View, after all. Everyone practiced surveillance. The studios would sometimes slip a spy into the screening room to monitor Kael’s responses, her sighs and whispers. Another might be stationed in the hallway to gauge the facial reactions of the departing critics. Some critics studied one another, trying to figure out how to position themselves on the film they had just seen. The dirty looks, the treacherous smiles—it made for pretty tense waits at the elevator, I can tell you. (“Ma Barker and her gang,” Warren Beatty once remarked as Pauline and company dislodged into the lobby.) After a screening, a group of us would repair to the Algonquin, where the waiters took turns presenting me with a roomy blue jacket to bring me up to dress code. The postmortems were often more entertaining than the movies themselves, but a real McCoypleasant surprises like Splash, Diner, and Stop Making Sense, or a disturber like Blue Velvet—generated giddy, cagerattling cross talk. Over time, the camaraderie settled into something more sedate. Critics became protective of their opinions, falling silent and frosting over when one didn’t “get” the quirky delights of Robert Downey Jr. But there was still an anticipatory tingle at the screenings themselves, an eager expectation.

Now, jump ahead to 1996. Picture a midtown screening room, a corporate box with gray carpeting. It’s winter. Determined to look like a man determined to appear conscientious, I would try to arrive early and snare a seat in the front row. As I gave the production notes intense scrutiny, I could hear the other reviewers and entertainment reporters begin to file in behind me. Such heavy feet. They shuffled like a prison work detail or refugees from the Russian front. Once plopped in their seats, they began to swap doctor’s-waiting-room complaints about other screenings they had schlepped to that week, how warm or cold some screening rooms were kept. “I could hardly breathe.” This litany of aches and pains took on the cranky age-old familiarity of a Herb Gardner play. Then the lights would dim, the lumps would settle, and a dusty beam would project a studio logo on the screen. Two hours later, lights up . . . and the survivors would slowly gather their belongings for the epic trudge to the elevator. Once we were all in our winter coats, it was like witnessing the migration of the woolly mammoths. When I remarked to people how downtrodden my colleagues on the film beat were, they’d automatically respond, “Well, it’s because the movies today are so awful.” True: a lot of them were awful—a paint-drying exhibition like Pedro Almodovar’s The Flower of My Secret had me climbing the inside of my skull. But they weren’t that awful.

It’s become a commonplace to claim that movies are worse than ever, limping to artistic extinction after a protracted slump following the glory days of the 70s, when Robert Altman, Martin Scorsese, Francis Ford Coppola, Brian De Palma, Steven Spielberg, Jonathan Demme, Paul Mazursky, and Bernardo Bertolucci were still young, vital, and mostly sane. Films flew off the grill then. Each week Germany’s Rainer Werner Fassbinder (the subject of a current retrospective at MoMA) seemed to produce a marbled slab of bohemian angst for Vincent Can by of The New York Times to enjoy. No question the 70s were a factory for funky verismo compared with the computer-designed, Disneyfied present. But it’s also true that a lot of the movies emblematic of that time have reputations a re-viewing won’t sustain. The hectic bustle of Altman’s Nashville now looks like a toxic spill and sounds like a garbled P.A. system. While the original Godfather holds up magnificently, Godfather Part II betrays its clumsy stitches. Scorsese’s Mean Streets, once a model of downtown neorealism, now seems all attitude, as do Five Easy Pieces and Carnal Knowledge. The 70s urban “look”—the grainy zoom-ins, the blotchy colors (algae greens and corduroy browns), the pimpmobile sound tracks—makes for a general itchiness on the screen. Nearly all of the Westerns from that period, from Altman’s McCabe & Mrs. Miller to Sam Peckinpah’s Pat Garrett & Billy the Kid, come across as mumbly, bedraggled. You’re aware now of what a druggy period it was, how quickly the highs turned into hangovers. There’s a lot of gangrene around the edges of this Golden Era.

Perhaps the perceived downturn in film today isn’t an unprecedented crisis or a historical inevitability, but part of the natural destructive/creative flux in any art form. Cultural pessimism is an ingrained habit. Intellectuals are always picturing The End. In the title essay of The Curious Death of the Novel, the critic Louis D. Rubin Jr. observes how often and how eagerly fiction and poetry have been declared kaput, a temporary lull having been mistaken for a termination. Perhaps cinema, like the novel, is always dying. “Something is always destroying literature,” Rubin writes, “but good books have managed to come along.” Similarly, something is always destroying cinema (the Hays Office, the studio system, the breakup of the studio system, TV, big-budget debacles such as Heaven’s Gate, superstar salaries), yet good movies manage to come along.

'It was in the late 50s and 60s, with the influx of foreign films by Antonioni, Bergman,Truffaut, Godard, Resnais, et al., that a new species was born: the cinephile.'

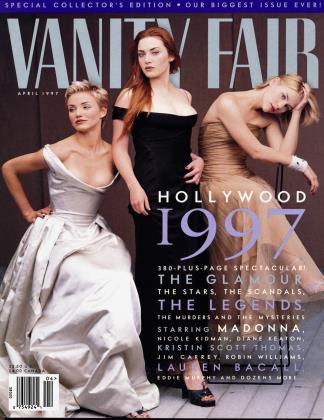

For all the gloom-mongering, the last few years alone have seen Pulp Fiction, Hoop Dreams, Babe, Before Sunrise, Leaving Las Vegas, Clueless, Crumb, Shine, The English Patient, Dead Man Walking, Fargo, Seven, Get Shorty, Angels & Insects, In the Name of the Father, Apollo 13, Braveheart, The Piano. With its con-artist plot twists and macho monkeyshines, The Usual Suspects may become as classic a noir as The Big Sleep, and Michael Mann’s Heat, a long lateral pan through industrial dead space and minimalist interiors, has unsurpassed passages of stripped-clean action (a bank stickup and subsequent machine-gun battle that seem to unfold in real time). The Jane Austen/costumedrama boom has tossed us a bouquet of talented young actresses—Jennifer Ehle, Kate Winslet, Kate Beckinsale. Shakespeare’s plays have been souped up (a neo-Fascist Richard III) and done straight (Kenneth Branagh’s full-length Hamlet). Independence Day was an undeniable event. I even liked the muchmaligned Mission: Impossible, not only for the set pieces but also for the witty way De Palma kept photographing Tom Cruise’s head as a sleek hood ornament.

I would argue that the state of movies today is not as mopey or dire as the state of movie criticism itself. Movie criticism has become a cultural malady, a group case of chronic depression and low self-esteem. This slump in morale reflects certain realities: the shrinkage of prestige and clout in the field (the indignity of seeing faceless hacks blurbed in every ad while your well-considered whoopee goes for naught), cutbacks in editorial space (both The Village Voice and The New Yorker now pen their reviewers in tight corrals). But it also seems rooted in a loss of romance at the very heart of the movie-reviewing profession, a love gone flat.

This sense of romance is rather recent. Often forgotten is the fact that some of the best movie criticism was written as a jazzy sideline or a ferocious fan’s notes. James Agee always had other projects as he riffed along in The Nation or Time in the 40s, occasionally knocking off a dozen movies in a single column. Otis Ferguson and Manny Farber, writing at about the same time in The New Republic, were also idiosyncratic soloists. It was in the late 50s and 60s, with the influx of foreign films by Antonioni, Bergman, Truffaut, Godard, Resnais, et al., that a new species was born: the cinephile. This educated viewer didn’t dip into the theater for a dark swim or a quick fix. The cinephile lived for Film. Movie theaters were houses of worship, a womb, a tomb, a secret catacomb. For the cinephile, film was an uppercase experience, religious, psychological, and erotic; a bathysphere into the unconscious; a violation of taboo. “For cinephiles, the movies encapsulated everything,” Susan Sontag recalls in “The Decay of Cinema,” an essay published last year in The New York Times Magazine. The cinephile tended to dine on subtitles, foreign films being spiritual, true-to-life, and art-infused compared with the Hollywood-billboard images in the toothpaste reign of Rock Hudson and Doris Day.

Then, in 1967, everything changed. Cinephiles no longer had to import their art orgasms from abroad. The film revolution came home. Thirty years ago saw the release of Arthur Penn’s Bonnie and Clyde, a momentous event in both movie history and movie criticism. Controversial at the time for its staccato violence, comic flippancy, and Freudian cool, Bonnie and Clyde is now recognized as the beginning of the American New Wave—the onset of the onslaught that would bring us 2001: A Space Odyssey, The Wild Bunch, The French Connection, Coppola, Scorsese, Spielberg, the whole shebang. It was Pauline Kael’s bravura championing of Bonnie and Clyde in The New Yorker—a thumping essay written in response to Bosley Crowther’s dismissive review of the film in the Times (“strangely antique, sentimental claptrap,” he called it)— that signaled the end of the gentlemanhack approach to film crit in the weeklies that had prevailed since the deaths of Agee and Ferguson. Over 6,000 words long, an almost unheard-of amount for a film review at that time, Kael’s essay still has the explosive force of pent-up energy that’s finally found its opening.

Once Kael was hired as a movie critic at The New Yorker, alternating six months of the year with the more belletristic and impressionistic (read: loopy) Penelope Gilliatt, she began to dominate the urban-intellectual nervous system as surely as did Norman Mailer after the triumph of Armies of the Night. Like Mailer’s, her writing ran on adrenaline and connected with the collective libido. Her reviews were long, pinpoint-detailed, funny, argumentative, and, most of all, alive. They had a rush. Combining the AgeeFerguson-Farber flair for slang and the cinephile’s unflagging devotion with a bullshit detector all her own, she could see right through the clinical chill of a Stanley Kubrick (“The only memorable character in his films of the past twenty years is Hal the computer”), the toy machinery of a Neil Simon (“It’s not Neil Simon’s oneliners that get you down in The Goodbye Girl, it’s his two-liners. The snappiness of the exchanges is so forced it’s almost macabre”). Since she came to the post relatively late, at the age of 49, she had an arsenal of seeing/reading/listening life experience to deploy. (Some of today’s younger critics strolled right out of Harvard into The Boston Phoenix.) Until her retirement in 1991, Kael enjoyed a great critical run, the greatest since George Bernard Shaw on theater, and, unlike Shaw, she doubled as a role model. With the ascendance of Pauline Kael, movie criticism evolved into more than a sideline, more than a career. It became a passionate calling.

^Movie criticism has become a cultural malady, a group case of chronic depression and low self-esteem.^

Now comes the sad part.

CASE STUDY No. 1:

The Lost Flock

Outgoing and generous (O.K., sometimes a little nudgy), Kael attracted and promoted same-wavelength writers, who came to be dubbed “the Paulettes.” Not every friend of Pauline’s qualifies as a Paulette. NPR’s Elvis Mitchell, for example, has a humorous, at-ease quality that’s personally his. Veronica Geng, who reviewed movies at the Soho Weekly News as if she were slashing tires, was a nut for Kael nonfavorites such as Bronco Billy and John Carpenter’s horror movies. I’m a longtime friend of Pauline’s, but detest Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom (which she adored) and love Vertigo (which didn’t even make it into her 5,001 Nights at the Movies), so where does that put me? No, the true Paulettes are those critics who still have one eye and ear cocked to Pauline’s opinion as they try to re-create her glory days and make each review an event. They write as advocates, both feet on the accelerator. To name names: Steve Vineberg (The Threepenny Review, The Boston Phoenix), Polly Frost (formerly of Harper’s Bazaar and Elle), Peter Rainer (L.A.’s New Times), Charles Taylor {The Boston Phoenix), Stephanie Zacharek {The Boston Phoenix), Michael Sragow {SF Weekly), Hal Hinson (recently departed from The Washington Post), and David Edelstein {Slate). Their gospel remains Kael’s influential essay “Trash, Art, and the Movies,” published in Harper’s in 1969. A necessary, liberating piece when it appeared, it has been superseded by the triumph of pop culture over high culture, something Kael herself acknowledged in a recent interview. “I don’t think anybody who wanted a recognition of [pop] wanted it to be recognised as the sole art of America.”

The word hasn’t filtered down to the Paulettes. They still write as if “trash” (the good kind—blatant, vital, sexy) were in danger of being euthanized by the team of Merchant Ivory. Gentility is the enemy—we’re drowning in crinoline! they cry. Bring back hot rods and cheap lipstick. (Never mind that The Remains of the Day is superior to anything Altman has done of late.) The problem for the Paulettes is that even casual readers know the difference between a strong original voice like Kael’s and a reedy echo. No one is heeding the Paulettes’ adenoidal Tarzan yells on behalf of untamed expression. Lacking a responsive audience that shares their urgency, the Paulettes are now reduced to writing for second-tier publications, using their underdog status to champion lost causes and pet losers, like the latest Walter Hill film or the career of Eric Roberts. They’re preaching in a vacant lot. Since for them movie criticism is a calling, the Paulettes are like staunch Catholics stuck in a bad marriage: they can’t leave. One Paulette I know was asked to review a book for a Boston paper. “But that would be writing about writing,” he blurted, scandalized by the very suggestion. Writing about writing—a.k.a. literary criticism—is something that’s been around for three, four hundred years, but to him it was a sneaky ploy to mess with his mind. He has since relented and reviewed an actual book. It was a movie book, which made it O.K.

CASE STUDY No. 2:

The Man Who Mistook a Movie for a Meteor

If the Paulettes are poor little lambs who have lost their way (a support group in need of a support group), David Denby, the film critic for New York magazine, is the boy who cried wolf. Easily excitable and always “concerned,” Denby first saw the face of cinema crack with Staying Alive (1983), Sylvester Stallone’s bombastic sequel to Saturday Night Fever. Rushing to the ramparts, he warned, “This is no ordinary terrible movie: it’s a vision of the end. Not the end of the world, which will probably be quieter than Staying Alive, but the end of movies (which amounts to the same thing). As you watch it, the idea of what a movie is—an idea that has lasted more than a half-century—crumbles before your eyes.” Somehow cinema and the world survived, but a decade later, Denby spotted another menace hurtling earthward: Joel Schumacher’s Batman Forever. The cataclysmic force of this film was such that Denby beseeched PBS host Charlie Rose to convene an emergency movie panel that consisted of himself, Janet Maslin, and Stephen Schiff. On the air, Denby deplored Batman Forever as a merchandising monster and mad kaleidoscope trashing all spatial and narrative logic. “One reason we all seemed to like Clint Eastwood’s movie The Bridges of Madison County so much was that it was coherent in space. And I don’t want to make this academic, but there’s something definitely gone from movies forever if this kind of thing can be a gigantic hit and not bother people that way.” One doesn’t want to defend Batman Forever, a homoerotic travesty accenting the latest in erect-nipple rubber formwear. And certainly the increased firepower of movies has made them more battering. But if the alternative to disassociation is the rusty, leaky faucet of Bridges of Madison County (each slow drip like the tick of a clock), the hell with it, as Pauline might say.

'"Ma Barker and her gang,” Warren Beatty once remarked as Pauline Kael and company dislodged into the lobby.'

Unlike the Paulettes, Denby has managed to find a door out of his malaise. In Great Books (Simon & Schuster, 1996), his widely reviewed account of studying the classics again at Columbia University, an injection of Nietzsche helps restore Denby’s faith in cinema. Reading Nietzsche makes him tingly inside, ready to rock. “By now, my taste in ‘great books’ had become clear: I was drawn to energy, play, vivacity, speed, perversity, and by means of these attractions, I sensed, in a roundabout way, that my love of movies couldn’t have died, and would never die, no matter how urgently literature now called, for those were among the qualities I most enjoyed in movies.” He sounds like a man who has found equilibrium, yet one suspects the subject could have another serious worrywart attack any minute. He should be kept under close observation and humored whenever possible.

CASE STUDY No. 3:

The Crooner in the Crypt

obody sings the movie blues better than David Thomson, the author of the indispensable Biographical Dictionary of Film (one of the few reference works with a soulful subtext) and currently the film columnist at Esquire. He’s the last of the true romantics, the master of melancholy. Where Denby blows steam, Thomson broods beneath the spotlight. He always writes as if he were stranded in a bar at closing time, like Humphrey Bogart in Nicholas Ray’s In a Lonely Place. One of the few critics with original perceptions (I’ll never forget his describing Lisa Bonet as being as fresh as the gardenia in Billie Holiday’s hair), Thomson has a tendency to introject his own dreamy longings into Hollywood hero worship when he goes wide. His ambitious books on Orson Welles and Warren Beatty are padded and misshapen by fancy ruminations on money, fame, sex, and genius. In shorter pieces, however, his spells can have the sad self-enclosure of a Frank Sinatra ballad.

His first column for Esquire (December 1996) found him contemplating the spiritual condition of the American movie house. What a dump. “The place where ‘magic’ is supposed to occur has seemed a lifeless pit of torn velour, garish anonymity, and floors sticky from spilled soda.” What’s on the screen ain’t so hot, either. “This is not just a lamentation that movies are in a very bad state. Rather, I fear the medium has sunk beyond anything we dreamed of, leaving us stranded, a race of dreamers.” “Who Killed the Movies?” asks the title of his debut column. He points the bony finger of guilt at Steven Spielberg and George Lucas, whose summer blockbusters Jaws and Star Wars turned audiences into sensation junkies and transformed the movies into soulless technocratic entertainment. Thomson’s indictment of the blockbuster mentality is a familiar dirge. What’s distinctive is his tone. He handles the decline of Hollywood with almost fawning lechery, as if he were arranging bodies in the morgue or the wax museum into tableaux, crooning over their smooth, dead features. He could be the caretaker of Sunset Boulevard. It’s perversely comic of Thomson to use his opening column to tell his Esquire readers, in effect, “The show’s over, folks, go on home.” His elegant fatalism seemed to leave him no next move. What do you do for an encore after you’ve announced your field is dead?

Ah, never underestimate a seducer. Thomson hasn’t been a former admirer of Warren Beatty and James Toback for nothing. His next column again found him in his lair, working on his mystique. “I write about film, in the dark if I must, with notepad and pen ...” After vamping a bit about the inability of mere language to capture the fleeting luminescence of film (yeah, yeah, yeah), he finally breaks down and brings himself to discuss an actual movie— The English Patient, of which he says that, in the transition from Michael Ondaatje’s original novel to the screen, “something wonderful and mysterious has happened.” He proceeds to marvel at its entangled intimacies and rapturous interplay of faces. In closeup, Ralph Fiennes and Kristin Scott Thomas are revolving moons. “Two faces in the night, seeing and being seen—no other medium can make such conquests so simply.” He likes it! He more than likes it! “To watch a film is to fall in love ...”

'Nobody sings the movie blues better than David Thomson.'

Thomson didn’t pause to note the irony. He had performed funeral rites over the art of film in his first column, only to find a masterwork to cheer in his second. It’s an irony that runs through the oeuvre of so many gloomsters. They keep tracing the dying arc of a tragic decline while being dazzled by individual gems. (Thomson found redemption in Leaving Las Vegas.) Few critics, for example, intellectualize with grimmer resolve than Terrence Rafferty of The New Yorker. His reviews establish their thesis or controlling metaphor in the opening paragraph and then work that baby like an Ikette. Rafferty, like Thomson, issues frequent low-moan lamentations. Yet peruse his old reviews and you’re surprised by how many raves he’s written, often for movies no one in his right mind would want to endure {Cobb, Wild Bill, Beyond Rangoon). Another tactic, much beloved by sullen Village Voice reviewers, is to praise movies so obscure that simply getting to the theater counts as a quest for the authentic. A 1996 Jean-Luc Godard video provokes the Voice’s Amy Taubin to announce, “And though compared to other recent Godard films 2 x 50 Years of French Cinema is no more than a sleight of hand, it’s nevertheless the first (and maybe the last) best film of the year.” Taubin published her bleak praise of Godard in January of this year, having little faith in the 11 months ahead.

To true despairers, the occasional godsend mattereth not. Each is but a bit of scattered, shattered light on a dark downhill road to certain doom. “Wonderful movies turn up, but movie criticism now is often a report on a vacuum,” Pauline Kael told an interviewer in 1994. A sentiment shared by Susan Sontag, who wrote, “If cinephilia is dead, then movies are dead too ... no matter how many movies, even very good ones, go on being made.” It may be the only time the two of them have agreed on anything. It’s almost a sign of hope. Even Siskel and Ebert, when not wagging their horny thumbs up in the air (“Way up!”), have joined the chorus. The consensus has become so broad and solid regarding the irredeemable fate of Film that I can’t help but wonder if the sentiment indicators have bottomed out, to borrow Wall Street language. At some point persistent gloom becomes so insupportable that something has to give—people get bored with being bored. I can see that, for cinephiles, movies aren’t the narcotic they used to be, and I can understand why critics are in the doldrums. I just don’t taste cinders and ash in the air. Critics need to get over themselves, and not treat the cinema as their personal cross.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now