Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

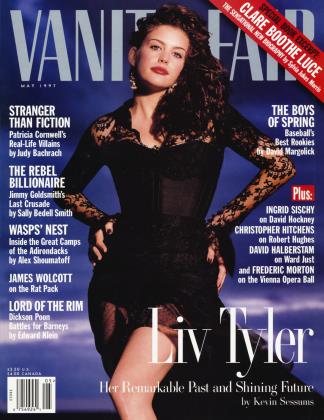

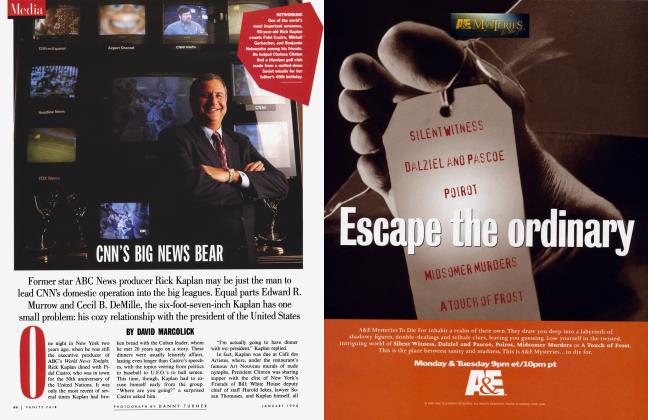

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowTHE BOYS OF SPRING

Sports

As the season opens, big-league rookies are dreaming of a career in the majors-and perhaps even a lasting place in Cooperstown

DAVID MARGOLICK

Dmitri Young took out a metal box and began showing off his prized collection of baseball cards of soon-tobe-famous rookies of years past. He is a rookie himself, about to become the starting first baseman for the St. Louis Cardinals. He is just 23, and it wasn't so long ago he was only collecting cards rather than appearing on them.

As someone who received a $385,000 signing bonus in 1991, Young has been able to upgrade his collection a bit in the past few years. Now he specializes in rare rookie cards and has several highly coveted ones. The most interesting are what one might call his doubleheader cards, pairing two top prospects rather than featuring only one: Johnny Bench and Ron Tompkins; Rod Carew and Hank Allen; Steve Carlton and Fritz Ackley. On the brink of the major leagues, all got equal billing, but now the matches seem incredibly incongruous. Bench, Carew, and Carlton are in the Hall of Fame; what ever happened to Tompkins, Allen, and Ackley?

Predicting success in baseball is a primitive science, far less refined than in football or basketball. That, after all, is why the record books are filled with busted "bonus babies" and cameo careers—"cups of coffee" in baseball lingo—and sleepers, such as Keith Hernandez in 1974 and Don Mattingly in 1983, who came out of nowhere. There is no shortage of explanations: the widely

varying conditions of play, the different rates at which talent matures, injuries, or simply because, as the sportscaster Bob Costas put it, the skills baseball demands are "quirkier." Still, mavens such as Allan Simpson, editor of Baseball America, predict that 10 or so rookies could break away from the pack of about 150 this year.

Most have yet to undergo the lobotomizing effect that fame has on major-leaguers.

Several have already made their bigleague debuts, but under baseball's wonderfully arcane rules (concerning at-bats, innings pitched, and number of days on the roster), they remain "rookies." Not all are profiled here, because they are already well known (Andruw Jones, who, at 19, became the youngest player to hit two home runs in a World Series game, for the Atlanta Braves, and who is a favorite for the 1997 National League Rookie of the Year), were unavailable for interviews (Vladimir Guerrero of the Montreal Expos, Karim Garcia of the Los Angeles Dodgers), or had uncooperative agents (Scott Rolen of the Philadelphia Phillies). But Vanity Fair caught up with seven of them.

They are a reminder that, whether or not it still embodies America, baseball, more than any other major professional sport, mirrors it in its demographic diversity. They fall neatly and almost proportionately into one of three groups: white, black, and Hispanic, with the lines occasionally blurred. All are young. They still live at or near home, still hang around with high-school friends, still refer to "Mom" and "Dad" a lot, still overuse such words as "awesome" and "outstanding." Most still talk with candor and authenticity, without strings of lockerroom cliches, having yet to undergo the lobotomizing effect that fame, money, routine, resentment, and fear quickly have on many major-leaguers. Most put up the kind of outlandish career numbers in high school and college that never last beyond the first few weeks of a season in the big leagues, where they all still have much to learn and much to prove, then prove all over again every week they play. Only time will show whether they will be superstars or, like some famous rookies of years past, will turn out to be the latest "can't miss"s who do, sometimes spectacularly or tragically.

-THE THROWBACK-

'Oxymoron" is not a word one finds in the lexicon of many ballplayers. But without exactly saying so, that's what Todd Greene, a catcher for the Anaheim Angels, says he is. "I'm a five[-foot]nine[-inch] power hitter," says Greene, who in 1995 became the first minorleague player in a decade to hit 40 home runs in a season. "That kind of doesn't go in the same sentence."

Signed by the Angels as an outfielder in the 12th round of the 1993 draft for a mere $5,000, Greene has built a career out of defying people's modest expectations. The 25-year-old native of Augusta, Georgia, is slow and, by professional standards, small. Late in his development, he had to learn to play baseball's most difficult position: behind the plate. Now Greene must compete with four other catchers for a spot on the Angels. But he could turn out to be a bonus baby of a different sort.

Balding, and with his remaining hair closely cropped, Greene looks older than his years. He is, in fact, a throwback—or, as he tells me one day over barbecue, sweetened iced tea, and a basket of Sunbeam bread at Sconyers Barbecue in Augusta, "a blue-collar-type player." He works hard. He has never smoked or chewed tobacco. He is married to someone he began dating at 16. He carries a cell phone almost sheepishly, fearful of looking like a hot dog.

When Greene played behind his high-school coach's house, the "ball" would be a sock tied in a knot, so as to save windows. Those who saw him play for Evans High School still remember his home run against Columbus, which reached the home-team high school's roof, 500 feet away. At Georgia Southern University, he hit another 88 home runs; only two college players—Pete Incaviglia and Jeff Ledbetter—have ever hit more. Still, the scouts were skeptical. They said he had a hitch in his swing and could hit only with the more potent aluminum bat, banned in the majors.

In 1994, when Greene played in the California League, the Angels tried turning him into a catcher. The transition was painful, literally—90-mile-per-hour fastballs leave neophytes with hands either bloodied or numb—and embarrassing for someone accustomed to perfection. After his first game, he told his wife he was quitting. But he persevered, learning not just how to catch curveballs but how to call games, placate umpires, throw out base runners, field foul pops, toss his mask, and maintain home plate and make it his. "I talked to Bob Boone [now manager of the Kansas City Royals], who was probably the best defensive catcher ever, and he told me he's still learning," Greene says. "If he's still learning, what does that mean I still have to learn?"

THE GOLDEN BOY

ne day last winter in Shreveport, Louisiana, Todd Walker drives up to the local Ramada Inn in his black Pathfinder. He is wearing sunglasses, though it is a gray and cheerless day. That morning he met with one of the three financial advisers who help him manage the $815,000 signing bonus he got three years ago from the Minnesota Twins, plus the thousands more he collects from card deals and endorsements. "What is it you'd like to accomplish?" he asks me in businesslike fashion as I hop into the front seat.

If there is such a thing as a sure bet, Todd Walker is it. Late last season the Twins conveniently traded away their incumbent third baseman, clearing the way for him. "As of this point, it's my position to lose," he says matter-offactly. For the 24-year-old Walker, the pieces have always fallen neatly into place. At six feet, he may not be so tall, but he is dark and handsome. (His brother is a model who has appeared in Glamour and Mademoiselle.) And he was born with a perfect swing. In his senior year at Airline High School in Bossier City, Louisiana, where Albert Belle Sr. was his hitting coach, he batted .525. At Louisiana State University he played second base and batted in more runs (and hit three more home runs) than did White Sox outfielder Albert Belle Jr., now one of baseball's highest-paid players. Only seven players were chosen ahead of him in the 1994 draft.

Walker is religious—he is active in the Fellowship of Christian Athletes and gave a tenth of his signing bonus to the First Baptist Church. But there should be plenty more to go around. When, while dining out with friends at a local resort called Cross Lake, he mused about buying an entire island there someday, it did not seem like fantasy. "I get business cards thrown at me from every angle," he says.

Around Minnesota, the talk is not whether Walker will make the team, but whether he'll be Rookie of the Year and how far into the next century he'll hold the job. Walker says he'd like to stay put. But rookies, or at least some gilded rookies, already know the score—that, as Walker says, "if you're going to get twice as much money to go somewhere else you're obviously going to take it. The truth is, no one is loyal anymore. You go where the money is."

A year ago Hernandez could not drive a stick shift; now he owns a Ferrari Spider, a Mercedes S500, and a Land Cruiser.

THE REFUGEE

n Versailles, the celebrated restaurant in Miami's Little Havana, the waitresses are fussing over 22-year-old Livan Hernandez, the handsome, boyish pitcher the Florida Marlins signed in January 1996 for an astonishing $4.5 million, including a $2.5 million bonus, the most ever paid to a non-major-leaguer. But part of baseball's romance is the idea that enormous talent lurks in remote or exotic places—every baseball fan knows that Mickey Mantle came from Commerce, Oklahoma—and no place is more remote these days than Cuba, even to the 675,000 Cuban-Americans, many weaned on baseball, who now live in Florida.

One waitress reminisces with him about life in Cuba, from which Hernandez, then playing for the Cuban national team, defected in Mexico in cloak-anddagger fashion a year and a half ago. He fends off another, who urges him to eat some paella from a gargantuan platter before him. "Six months ago he would have said, 'Give me another fork,'" says his agent, Juan Iglesias of the South Florida Sports Council. Dazzled by Wendy's and Lay's potato chips after a lifetime of privation, depressed over his separation from family, friends, and fiancee, worried about reprisals against his brother (also a star player and still in Cuba), crippled by his lack of English, Hernandez ate compulsively in his first year here, showing up at spring training, as The Boston Globe put it, "fatter than a Havana cigar." Sent down to the minors for more seasoning, he struggled, descending to Double-A.

Hernandez rebounded by season's end, which was capped by a threeinning appearance against the Braves. And with a new agent, new Spanishspeaking baseball friends such as the Oakland slugger Jose Canseco and Marlin teammate Luis Castillo, and new women to admire—his fiancee is but a faint memory as he currently covets two actresses in Spanish-language soap operas broadcast in Miami—he seems to have shaken off the blues and most of the fat. He now weighs 225, only 8 pounds more than he should. And he's picked up some English— "dancing," for instance.

Hernandez, who as a boy went to sleep with his bat and glove, already has the strut and style of a majorleaguer. Versailles is not a fancy place— ropa vieja goes for $6.85 plus tax—but for his visit there, Hernandez is wearing a Cartier watch with a gold band, a Versace ring, a gold bracelet and necklace, and a diamond stud. He also leaves a $20 tip for a $50 meal. All this from someone who, a year ago, had never used a credit card. He's already a fixture in chic South Beach and at Larios on the Beach, the Miami restaurant owned by Gloria and Emilio Estefan.

A year ago Hernandez, who had always ridden bicycles, could not drive a stick shift; now he owns a Ferrari Spider (for which he recently traded in his Porsche), a Mercedes S500, and a Land Cruiser. Why, I ask him, does he need three cars? "Because I like them and I didn't have them in Cuba," he replies in Spanish. "Why does someone have three women? You like to drive them differently."

To spur him on further, to show him "the fruits that grow from the tree of baseball," agent Iglesias takes Hernandez on periodic pilgrimages to Casa Canseco—Jose Canseco's lavish spread, complete with marble staircase, pet iguanas, and framed reproductions of figures from the Sistine Chapel ceiling, in the sterile gated community of Weston, Florida, near Miami. But with the logjam in the Marlins' starting rotation, Hernandez won't be living in anything similar soon. In fact, he'll be starting the season back in Triple-A.

Ten rookies could break away from the pack of 150 this year and make their presences known.

STUDENT OF THE GAME

He's been playing it since he was six, but Mike Cameron, who could be the White Sox right Fielder this season, can't get enough of baseball. He's read all the books about the Negro Leagues. He watches the highlights on ESPN again and again, looking for ways to improve his game. During his short fling in the majors in 1995, when Chicago played Cleveland, he approached Dave Winfield, then ending his distinguished career as a home-run hitter, and asked him, "What makes you so good?" Winfield looked at him as if he were crazy.

Cameron is sitting where he spent most of his childhood, at least after his parents split up; in his grandmother's house in a poor, black section of La Grange, Georgia, near the Alabama border. Just down Render Street is where he used to play ball with his friends, marathon games called only on account of darkness. With his grandmother working the second shift in a carpet factory, he was often alone, giving him an independence and introspectiveness one doesn't normally find in 24-year-old athletes.

If there is a rap on Cameron, an 18th-round draft pick in 1991 who signed for a $24,000 bonus, it is that he's "good field, no hit." Before a game two seasons ago in Kansas City, Walt Hriniak, the peripatetic and controversial hitting coach, tried to change his swing, telling Cameron that as things stood he didn't belong in the majors. Later that day, on an 0-2 pitch, swinging as he always swung, Cameron hit his first home run, into the decorative fountain beyond center field. Given Hriniak's doubts, it was doubly delicious. "It was pretty soaked," Cameron says of the ball, which he fingered lovingly as we spoke. By now he's seen the moment 20 times on videotape.

Cameron proves that for professional athletes there can be a charming middle ground between unabashed conceit and cloying false modesty. With boyish enthusiasm, he says he's on the verge of being "an all-star-caliber player." And while he won't want a $10 million house, he says, a $2 million one will do. "I don't want to be too greedy and I don't want to be too lowkey," he says.

A couple of springs ago Cameron walked up to Gene Lamont, the White Sox manager at the time, and declared, "I'm going to be your right fielder in the next two years." "I said it as a joke, but it's really true now," he says. Even though he'll be starting the season in Triple-A, Cameron still hopes to meet Willie Mays, whose number (24) he was given with the big club. He wants to ask him one question: " What made you so good?"

THE SAVIOR

Not so long ago Miguel Colon, whose hands have grown gigantic from a lifetime spent wrapped around machetes, begged his reluctant children to help out on the farm he works on a few hilly acres in Altamira, a crossroads hamlet in the northern Dominican Republic.

"The way I'm going to help you," replied his son, touching his right side, "is with this arm." But he was talking about pitching, not about harvesting coffee and cocoa beans.

Only a few years later Bartolo Colon's prediction has come to pass. After a spectacular season in the Dominican Winter League—where his earned-run average, 0.21, was the lowest in league history—he is poised to play for the Cleveland Indians, thereby becoming the latest in the uncanny number of major-leaguers produced by this small Caribbean nation.

FOR DETAILS, SEE CREDIT PAGE

Baseball's luster may have faded to the North; during those crucial years when tastes are set for life, young American boys now play computer games and watch basketball rather than hit Wiffle balls. But here there is no ambivalence. Near the Colons' simple tin-roofed house, where baseball mementos and pictures of Jesus Christ hang on the flimsy walls, where mice once tore apart young Bartolo's favorite jersey, three young boys toss around a battered ball the scuffed dark brown of a Dominican 20-peso note. The ragged outlines of an infield are only barely discernible; the wicked hops the ball takes off the pockmarked, gnarled ground instantly explain why so many Dominicans become great infielders.

Pitching in nearby Puerto Plata in 1993, the 17-year-old Colon caught the eye of the Cleveland Indians, who signed him for $3,000. In four minorleague seasons, he's compiled a record of 28-10; Baseball America called him "a comet hurtling toward the big leagues."

-THE PROUD ONE-

Until 23-year-old Dmitri Young smashed a crucial two-run triple for the Cards in the 1996 National League Championship Series, his most famous hit actually took place in the stands. It came in Wichita in 1995 when he pummeled a fan who called him a "fucking nigger." Officially, Young is contrite about the incident, for which he was suspended for 20 games. But probe a bit and he is still defiant. "You have your Goody Two-Shoes players, a lot of the white ballplayers, who say, 'Ah, just brush it off,'" he tells'me. "But I was talking with Bob Gibson and Lou Brock about it," he continues, referring to two of the Cardinals' greatest black ballplayers, "and they said they would have done the same thing."

Young, who was watching All My Children when I arrived at his house in Camarillo, California (his subscription to Soap Opera Weekly fills him in on the episodes he has to miss for day games), is a collector. His living room is strewn with a few of his 3,000 miniature "Hot Wheels" cars. There is also his collection of baseball cards, including one on which he appears with White Sox star first baseman Frank Thomas; with interleague play making its debut this season, the Cards will play the White Sox, so he can finally get Thomas to sign it.

In Montgomery, Alabama, Young made the high-school team as a 12-yearold and batted .584. As a high-school sophomore in California, he practically decapitated the opposing shortstop with a line drive hit as darkness fell upon the field. The next year, one of his home runs almost hit the batter (or the third baseman, or the pitcher, depending on whose version of the story you believe) in an adjacent diamond.

We walk into the Sports Fan-Attic, a memorabilia store in Camarillo run by Young's high-school buddy Steve Dunkle, where, symbolically enough, basketball cards are gradually usurping more and more space. But Dmitri Young cards, 63 different kinds, tracing his progress through the minors, take up a complete shelf. Many still sell for 25 cents. But if Young fulfills his promise the prices could quickly escalate.

Players recall how Dalkowski's fastballs tore an earlobe off one batter and gave an umpire a concussion.

FULFILLING A DREAM-

When 23-year-old, six-foot-tall Nomar Garciaparra booted a ball in his first game at Fenway Park last September, all hell broke loose. "It was 'My God, he's terrible, what's he doing out there?'" he recalls with a laugh. In Boston, he quickly learned, the scrutiny is harsher, the memories longer, the passions stronger.

The Red Sox have a glut of infielders, but on opening day Nomar Garciaparra—"Nomah Gahciapah" in Fenwayese—will be at short. Sox fans took to him, a first-round draft pick in 1994 from Georgia Tech who signed for $895,000, during his brief time with the team, and given his pleasing personality, his easy intensity, his young Ted Williams looks, his surprising power, and his sure hands, they are likely to forgive his very occasional mistakes. Maybe.

Anthony Nomar Garciaparra—the Anthony is for Anthony Davis, the former U.S.C. running back much admired by his mother; Nomar is his father's name spelled backward—grew up in Whittier, California. (Though of Mexican descent, he speaks only a smattering of Spanish, which made the bigotry he encountered at Georgia Tech that much more searing.) It was the game itself, rather than anyone who played it, that he worshiped. For him, baseball cards were strictly for flapping against bicycle spokes.

From age six or seven, Garciaparra told people he would be a major-leaguer. The only problem was size. "Mike Gallego was five eight," he recalls, referring to the utility player currently with the Cardinals, one of the smallest players in the big leagues. "I would sit home and pray, 'Just let me be five eight.' And when I reached it I was the happiest man in the world. I told my body not to stop growing. And I still haven't told it to stop."

THE FASTEST EVER

'Baseball is always talking about 'can't miss' players," said former Cardinal catcher Tim McCarver, who has spent decades watching the game, from behind either the plate or a microphone. "I've seen a lot of 'can't miss' players miss."

The list of famous disappointments is long. There's Steve Chilcott, the only player ever selected first in the draft (of 1966) never to play a single game in the majors (he was injured in the minors), for whom the Mets passed up Reggie Jackson. There's Brien Taylor, signed by the Yankees in 1991 for $1.55 million, only to ruin his arm in a bar brawl. There's Bob Nelson, dubbed "the Babe Ruth of Texas," who in the 50s failed to hit a single home run for the Baltimore Orioles or anyone else. There's Paul Pettit, baseball's first $100,000 bonus baby, who because of injuries, bad breaks, bad calls, and bad relief in a single game has a career mark of 1-2 rather than 2-1, a fact that gnaws at him nearly 40 years after he last walked off the mound. "I wish I had that more than anything else in the world," he said of that elusive second win.

But no player had more promise, or fell more spectacularly, than Steve Dalkowski, who, though only 57, now lives in a nursing home in New Britain, Connecticut, near the sandlots where, 40 years ago, he'd strike out 20 batters a game, where scouts from 15 major-league teams lined up to watch him. "No one could match your 110 MPH fastball, not Feller, Ryan, Seaver or Koufax," wrote Phil Rizzuto on a photo Dalkowski keeps by his bed. Debilitated by alcohol, unable to formulate complex thoughts, Dalkowski is still capable of primitive eloquence. "I pitched the same as everyone else," he said quietly. "It just got there faster."

After 34 years in the game Marlins manager Jim Leyland still can't predict success.

For some mysterious reason, since he was neither big nor strong, Dalkowski, who signed with the Orioles for $40,000 and a Pontiac in 1957, could throw a baseball faster than anyone before or since. Players recall how his fastballs tore an earlobe off one unlucky batter and gave an umpire a concussion, how errant pitches went through wooden backstops, leaving batters cowering and fans running for cover.

But Dalkowski had trouble with control, both with baseballs and bottles. In one incredible performance, he struck out 24 batters, but he also walked 18. Still, he was about to reach the majors in 1963—he'd been measured for an Oriole uniform and been assigned a locker—when, after striking out Roger Maris on three pitches in an exhibition game, something snapped in his left arm while he was fielding a bunt. His career ended, followed by 30 years of drinking and dissolution that stopped only through the intervention of a loving kid sister.

Somewhere in Dalkowski's story lies a lesson for today's rookies, about the combustible combination of superhuman talent, human weakness, pressure, and exploitation. Today, unable to focus very long or do much of anything besides snatch fragments of baseball memories, he cannot say what that lesson is.

THE SECOND-_ CRUELEST MONTH

n early March, as spring training has gotten under way, the Atlanta Braves and Florida Marlins, two teams that could well compete for baseball's grand prize this season, meet in Municipal Stadium of West Palm Beach, Florida. Before the game the clubs take turns on the diamond, where signs for local barbecue joints, a hometown divorce lawyer, and an exterminator line the outfield wall. Two related but distinct sounds— the sharp crack of a bat against a pitched ball, the duller, more muffled knock on wood of grounders hit by coaches—fill the languid air.

On the surface, the atmosphere is easy. Opposing players greet one another—and managers greet umpires—like long-lost friends. Some stars, betternatured and more available than they will be as the season wears on, sign autographs on the sidelines, part of chastened baseball's effort after the strike of 1994 to atone to its fans. This time of year, no line drives are worth diving for; even the fly balls seem lazier, and when they're beyond reach, outfielders toss up gloves to stop them.

But to this year's rookies, it's time to produce. The Marlins' new manager, Jim Leyland, leans on a bat by the cage, scrutinizing what he's got. Famed for his saltiness—local reporters must now decide whether to clean up his language or sprinkle it with dashes and asterisks—Leyland himself never made it past Double-A, and batted only .222 down there. Thirty-four years he's spent in the game and still, he admits, he can't predict who will succeed and who will fail.

"There are exceptions to the rule— my mom could watch Barry Bonds and see he would play in the big leagues— but for the most part no one knows for sure," he says. Scouts study raw talent on sandlots and high-school diamonds, and somehow extrapolate, prognosticate, from what they see. To Leyland, they are baseball's most valuable players. "I don't know how the fuck they do that," he says with about as much wonder as any hardened baseball man can muster. "I'm glad I just have to manage."

EVAN KAPLAN

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now