Sign In to Your Account

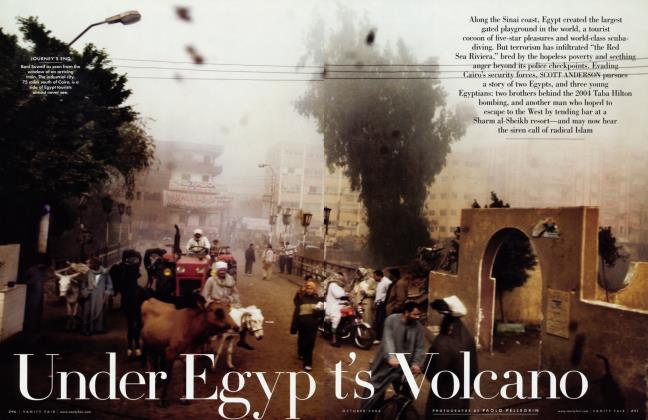

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe Last Goddess

Hollywood was utterly baffled by Luise Rainer, who became the first star ever to win the best-actress Oscar two years running, for The Great Ziegfeld (1936) and The Good Earth (1937), then fought bitterly with MGM chief Louis B. Mayer and left the studio forever. At 88, with her first film in more than 50 years due here soon, Rainer gives MARIE BRENNER the exclusive story of her youth in Europe as Hitler rose to power, her passionate, doomed marriage to playwright Clifford Odets, and her friendship with Albert Einstein

It was always said about Luise Rainer that she was thorny, skittish, and difficult to manage. At the height of her career, in 1938, she shared a luxurious cottage on the MGM lot with Metro’s other screen goddesses—Greta Garbo, Joan Crawford, and Norma Shearer. She was “an echo of Europe,” Anais Nin wrote of her, noting her ethereal nature and unpredictable ways. Seeing her for the first time at a dinner party in October 1940, Nin described her arrival in a “white floating dress.” She wore no makeup and had a childlike impulsiveness, combined with “a sadness older than the world.”

Rainer came to Hollywood from Vienna in 1935, and her movie career was incandescent and ephemeral. For her, the Hollywood years “are not even a fraction of the picture.” Romance and passion have defined her long and supremely dramatic life. Rainer was a superstar, the first performer to win an Oscar for best actress two years in a row, for The Great Ziegfeld in 1936 and The Good Earth in 1937. And then, inexplicably, her days as a star were over, as if the Oscars had come with a curse. “I felt hunted,” Rainer said recently in London of that time in her life. “I will never forget those years. ... I was very unhappy.”

After Rainer fled MGM, she encountered Anais Nin again. Watching Rainer dress, Nin was struck by how she rejected the “movie-star hats, the movie-star shoes, movie-star furs and bags” and reached instead for “the simplest beige dress,” a delicate skullcap with a veil, and “the simplest shoes.” In bed, Nin observed, Rainer slept with a blanket pulled over her head, as if she were a child frightened by a nightmare. Nin wrote in her diary what appeared to be the essence of Rainer’s life. “Luise’s image of herself and the image on the screen do not match. . . . She repudiated the worship, the flowers, the love letters addressed to her, as if the person on the screen were a fraud.”

Mention The Great Ziegfeld to a movie buff and wait for the Luise Rainer imitation. The telephone scene has become a classic riff: Rainer is a quivering bundle of suppressed grief and feigned joy as the soubrette Anna Held, the abandoned wife of the theater impresario Florenz Ziegfeld, played by William Powell. She has just learned of her ex-husband’s marriage.

Ooh . . . Hello, Flo ... I am so happy for you today. I could not help but to call on you and congratulate you . . . Wonderful, Flo, never better in my whole life! . . . Oh! It is so wonderful. I am so happy. Yes! And I am so happy for you too, yes? ... It sounds funny for an ex-husband and ex-wife to tell each other how happy they are,oui?

She hangs up tremulously and, after a beat, collapses sobbing onto a chaise.

Rainer became celebrated for her intuitive acting and emotional range; she was a Method actress years ahead of her time. “I never acted,” she said. “I felt everything.” Like Meryl Streep, she seemed to have an aversion to anything artificial; her contrarian, bookish nature set her apart. Rainer was an anomaly in the studio system: she did her own hair and was often seen in white chinos and tennis shoes. “Let’s show them that this is a world safe for poets!” she once scribbled on a napkin and gave to her husband-to-be, the playwright Clifford Odets.

As the peasant O-Lan in Sidney Franklin’s The Good Earth, opposite Paul Muni, Rainer dies memorably, in another famous movie scene, relaxing her feeble grip on two pearls which she treasures. Once, during the filming, she was so overcome that she sat on a curb at Metro, weeping. “A big limousine comes by and stops—it was Joan Crawford,” Rainer told me. “She said, ‘Luise, what happened? Why are you crying?’ I did not want to sound like a phony about acting, so I told her that I had received terrible news from Europe about my family.” After Rainer returned to her house in Brentwood that evening, a large bouquet of flowers from Crawford arrived.

Rainer’s disappearance from Hollywood was considered unfathomable, a neurotic quirk, perhaps, of a formidable talent. “My so-called career went sky-high, but my private existence went down to hell,” she told me.

Late morning, Eaton Square. Luise Rainer lives in an apartment in a Regency building with a legacy: Vivien Leigh lived here at the end of her life. On the telephone, Rainer has been precise, Germanic, bossy, taking my measure. “You will arrive at 11 A.M. It is impossible to come anytime sooner. Impossible!” When I ring the bell, her clear European voice calls through the intercom, “You are here! My torturer has arrived!” A tiny woman peeks out the door. She is all eyes, a Pierrette, with a vamp’s seductive come-on and a strategist’s cunning. She pulls me to her with both hands. “Come in! Come in! You must have coffee. You must eat something!”

"Clifford once said a terrible thing. He said, 'Darling, if every you want to commit suicide, do it in my arms.'"

Rainer moves through her apartment like a ballet dancer, but with daunting speed. Her drawing room is fastidious and filled with antiques. “I hate disorder,” she says. There is a portrait of the star as a young woman, dun sofas, and a large Ecuadorean religious retablo, which dominates the room. Rainer’s posture is that of a girl, and she weighs what she did when she was at Metro, 90 pounds. She wears beige trousers, a matching cashmere sweater, and a silver choker. On the matter of her age, Rainer is succinct: “I am a freak of nature. I am 87! When you think how old I am! And I am proud of it!” She says, “I want to show you something. I have never had a face-lift! Look!” Her hands dart to her scalp; she flattens her hair. “No scars!”

She hides behind tartness; her conversation is punctuated with synthetic commands, theatrical gestures, and grand sighs. Her drawing room is her stage. “Darling, I have had so much love in my life! How will you be able to capture it all?” she asks me. The expressions on Rainer’s face shift quickly; she is by turns excited, imperious, alluring. “My mother should walk around with the little man with the clapboard,” says Francesca Bowyer, Rainer’s 50-year-old daughter, who lives in Bel Air. The actress Anne Jackson says, “Every time I am out with Luise, it is like a three-act play by Euripides. Walking her dog can become the end of the world.”

Rainer instructs me to follow her to her study and moves toward a of bookshelves. Her two Oscars gleam from a high shelf. She very obviously does not call my attention to them. “They mean nothing to me,” she says coolly when I point them out. “It was expected that I do my best work. . . . Now, darling, this is what is important!” she says firmly, presenting me with a Penguin edition of interviews with history’s luminaries—Trotsky, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Mark Twain. “It is a very difficult thing to do a proper interview.” Of earlier stories about her, she says, “Darling love, all of these things are bullshit. And therefore I don’t Want you to write bullshit. I would come personally over and kill you.” Later she says, “My life has been so full. To come to the essence of one’s existence, one must speak of things that are both true and not true. . . . For every statement, there is a counterstatement. . . . You will never be able to write about my life! There is too much.”

"I am a freak of nature. I am 87! And I am proud of it! ”

CONTINUED ON PAGE 394

CONTINUED FROM PAGE 362

I have come to London to see her because, for the first time in more than 50 years, she is in a movie, filmed in Hungary, of Dostoyevsky’s The Gambler, starring the English actor Michael Gambon as the novelist. Her decision to play the part seems of a piece with her personality: the imp of the perverse. “Everyone thinks I am dead!” she tells me. “They all say, ‘Luise Rainer, she can’t be still alive!’” Rainer’s 15-minute appearance is high-camp relief in the ponderous film. Carried in on a sedan chair, wearing a black dress and feathers, she plays an aristocratic matriarch in a world of croupiers. “Did you think I vould send a telegram?” she asks with bravura, after surprising her son, a gambling addict. Rainer’s face, gloriously lined and filled with intrigue, shines from the poster at the theater on Shaftesbury Avenue.

One afternoon Rainer tells me that she is flying alone to Africa in December on the eve of her 88th birthday. My obvious surprise makes her snappish: “If you were my daughter, you would try to lock me up in a cell to prevent me from going, but I must be free! ... If I am killed, I’ve had an extraordinary life. You will not be able to prevent me from going! I must live!”

Her life has been an ongoing rebellion against any form of domination. She was reared in a well-to-do family in Hamburg. Rainer’s father, Henry, orphaned at seven, had been sent to Dallas, Texas, to be raised by a prosperous uncle in the import-export business. He had crossed the Atlantic on a schooner, and two decades later, in 1907, returned to Europe. While in Dallas, Rainer had become an American citizen, which would save his life during World War II. In Essen on business, he saw a beautiful young girl on a swing at a carnival. That night he was invited to dinner to meet with a local industrialist. The hostess’s sister, who was also at the dinner, turned out to be the girl on the swing, Emily Konigsberg, a gifted pianist. Rainer’s future in-laws were assimilated Jewish hauts bourgeois who lived in a world of privilege, with ladies’ maids, daily visits from the coiffeur, embroidered trousseaux, and holidays at the seashore.

Rainer ruled Emily and their three children like a tyrant, Francesca Bowyer says. She believes that her mother felt diminished by her father’s harsh ways. “The family was terrified of him,” she tells me. “My mother had to spend so much time proving how intelligent she was.” Rainer recalls moving from city to city when she was a child, as her father expanded his oil-and-soybean importexport business. “I changed school eight times,” she says. “I lived in Munich during the terrible flu epidemic . . . and then we went to Switzerland,” where, she says, “I skied to school.” The family settled in Hamburg in 1922.

Rainer once told Odets that she was “a seven-month child, and I am missing those two months and I want them back.” Her father often made “terrible scenes. ... He would leave the house.” Rainer, her father’s favorite, viewed him as “a tragic figure,” a sort of Don Quixote with a dim sense of reality. When she announced to her parents that she intended to be an actress, she says, her father “implied I was a whore. He said, ‘It is a low and vulgar profession.’ ... I was thrown out of my house at age 16 or 17, and I had to live on apples and eggs!”

ften, with Rainer, I felt that I was obOserving her through a transparent bubble, taking down a narrative of her life not unaffected by illusion. “I’m going to tell you everything,” she had said melodramatically on our first afternoon, and I occasionally imagined that I was an audience of one, lost in a world of vanished splendor, which Rainer had neatly shaped into perfect scenes. As a teenager living with her grandparents outside Dusseldorf, she told me in the plummy tone of an ingenue, she appeared one day at the door of an important theater belonging to Louise Dumont, a well-known theater owner of the era. “I presented myself to the secretary and said something completely idiotic, like ‘I would like to have a job for next season.’” She was 16 years old, with a perfect, heart-shaped face and a fragile beauty. Granted an audition, she did a scene from Schiller’s Joan of Arc.

In her first months at the Schauspiel Haus in Diisseldorf, she took the lead in Frank Wedekind’s sexually frank Spring Awakening. Soon Rainer was sent for by the great director Max Reinhardt. She eventually joined his Vienna company and became part of an impressionistic acting tradition which emphasized Reinhardt’s rejection of the naturalistic style.

Rainer flourished in this atmosphere, although she also acted elsewhere, starring in an adaptation of Theodore Dreiser’s An American Tragedy and Shakespeare’s Measure for Measure. Reinhardt’s company was an insular culture, protected, they believed, from the Fascism that was sweeping Germany.

All around them, however, were signs of the inevitable. In 1933, while Rainer was in Berlin performing in a French play, Sardine Fisherman, she was called to a meeting with producer Victor Barnovsky, who wanted to cast her as Cleopatra. Sitting in his office, Rainer looked out the window. Later, she wrote in her unpublished memoirs:

I saw . . . first a cloud of smoke and flames, high flames licking the sky. ... It was light, then dark. The Reichstag went up in flames. How could I tell what Barnovsky was talking about? Adolf Hitler was to declare my race had “poisoned blood.” . . . Barnovsky, his back to the window, was angered by my total inattention. “Don’t stare out the window. Whatever this is, think of your work and nothing else. This all has nothing to do with you.”

Rainer was apolitical; caught up in her life as a young star, she was driven by emotion. The expressionist playwright Ernst Toller was in love with her, and she became enamored of a well-known director. “There were so many men,” she told me. On the morning after her first sexual experience, she twirled across the stage exclaiming, “I’ve lost my virginity!” Scorned by her father, she had made the theater her family. In Vienna she collected encomium after encomium. “How do you do that?” Max Reinhardt himself asked her after one performance. The company had the feeling almost of a religious cult, equals plying their art and being paid almost nothing for it. The growing tensions in the world outside were but a blip.

Soon Rainer began to worry about her parents. “This fellow Hitler is nothing, he’s a housepainter,” her father said. Henry Rainer published vigorous letters attacking Hitler. Rainer did not believe in religion; he had turned against it as a boy, and now convinced himself that the Nazis were unaware of his wife’s Jewish origins, which were never discussed in the house. The Rainers had the deep ambivalence about their religion which was an integral aspect of much of the German upper middle class. All of the children were reared “wild, with no religion at all,” Luise Rainer said. She used Goethe’s word Wahlxerwandtschaft—elective affinity, meaning, for her, choosing one’s own relatives—to describe her ties.

Rainer was very aware of her history. “I never made a secret about it,” she said. “This whole thing about being Jewish . . . it’s a very American thing. In Europe, on the Continent, people of the upper class never talked about Jewishness or not Jewishness. . . . Then came Hitler. Then this became an issue.”

Rainer was besieged by admirers, who filled her dressing room with flowers. She had a rich girl’s willfulness; she gave the impression of being entitled and oblivious, a dangerous set of traits. In Frankfurt, soldiers worked as stagehands at the theater, wearing brown shirts and heavy boots. “I said to them, ‘Would you do me a great favor? Get rid of those blasted boots and put on slippers, as stagehands normally do!’” Another time, as part of the play she was in, she asked the young actress who played the maid to bring her flowers onstage so that the audience could see them. The Gestapo visited the theater and accosted her. “I was told that I had told the stagehands to strip their uniforms! And that I had asked a talented young actress to bring me flowers, as a page boy to a queen!” Because of her status as a star, however, Rainer had been given a special title: Honorary Aryan.

She was soon offered an escape from the growing chaos in Frankfurt—a European tour with Reinhardt’s production of Pirandello’s Six Characters in Search of an Author. The playwright accompanied the tour, and Rainer recalls him as “a birdlike little man, pixilated.” In Vienna one night at the theater, she met a young, rich Dutchman, who later arranged a party so that he could see her again. Rainer fell deeply in love with him. He pursued her everywhere, flying her in his twoseater plane over the Dutch tulip fields. “He was everything to me,” she said.

In Vienna, a scout from MGM saw her perform and asked her to go to London to read for the film version of Hemingway’s A Farewell to Arms. The Dutchman insisted on flying her there for her screen test. As Rainer unpacked, she realized she had brought two left silk shoes. She became hysterical because she could not afford new ones, and she would not allow her lover to buy them for her. “Shoes from a man! I would never have accepted,” she said. He gallantly crossed the Channel to Amsterdam, where her luggage was with friends, and returned to present her with her right shoe in a basket. Within months, he would be killed when his plane crashed in Africa.

Rainer was invited to Hollywood in 1935. Mourning her lost love, she had fallen into an affair with his brother, who physically resembled him. “I had mixed them up in my mind,” she told me, “but they were not at all alike.” She crossed on the Ile-de-France and celebrated her 25th birthday on the ship. The violinist Mischa Elman serenaded her in the dining room. During the trip she discovered she was pregnant. “It was a romantic, idiotic thing! I thought that the child would be like [her dead lover]. ... It was a young foolishness.” Walking Johnny, her Scottish terrier, on deck, she realized she could never have the baby and keep her career.

“Darling, don’t make me a tragedienne,” Rainer said of this period. “When I went to America I thought they would take one look at me and send me home again. ... I never dreamed of becoming a movie actress, never. My father always talked about America. I could see that America that I’d always heard of.”

Rainer was taken from the train station to the Beverly Wilshire Hotel, and at the desk she spotted Gary Cooper. “I nearly fainted,” she said. She then went for a walk through Beverly Hills. “There were flowers all over! I couldn’t believe all of the windows were open, and the lights were on, and it was like a theater. You could see what the people were doing!”

She was invited to a party at the singer Jeanette MacDonald’s, where she met MGM’s then reigning star, Norma Shearer, and her husband, producer Irving Thalberg, as well as the emigre director Ernst Lubitsch. Soon she was sent for by Louis B. Mayer’s closest studio aide, Eddie Mannix. Rainer had no sense of American slang. “They had me read, then they slapped me on the back and said, ‘See you later!”’ She thought she had been invited to a party. Next they drove her around the lot at Metro, through the back streets and onto a set where Johnny Weissmuller was filming a Tarzan movie. The drive continued. At one point Luise asked the driver what set they were on now. Beverly Hills, he said.

She was given a small house in Santa Monica, down the beach from Shearer and Thalberg. Rainer took long walks with her dog and studied English. One day she met the writer Anita Loos, who asked her, “Aren’t you that girl who just came from abroad? The studio is looking all over the world for a woman to take over Myrna Loy’s role in Escapade. You should call the studio.” With calm hauteur, Rainer told Loos, “I’ll wait until they come to me.” They did. She was cast in Escapade, a turn-of-the-century Viennese romance, opposite William Powell, who was so impressed with her that he badgered Louis B. Mayer about her billing. “ ‘You have to star that girl or I look like an idiot,’ he said,” Rainer recalled. “That is how I became a star!”

From the start, the studio played up Rainer’s waiflike appeal. In clips of the period, there is no mention of the fact that her family owned a large importexport company or that she was German; to avoid growing anti-German sentiment, the studio called her Viennese. MGM made plans to typecast her as the abandoned wife, the woman scorned. After Escapade, she was again paired with William Powell, in Robert Leonard’s elaborate film biography, The Great Ziegfeld, which featured cameos by vaudeville stars Ray Bolger and Fanny Brice.

According to Rainer, “Louis B. Mayer did not want me to do that part. Suddenly I was a new star, and they had not expected that! . . . The producer Hunt Stromberg said to me, ‘Please go to Mayer and tell him that you would like to do it.’

“I was very unsophisticated! They had written the telephone scene. It was nothing. I said, ‘Can I write that scene?’. . . And I went to Louis B. and said, ‘Look, I very much want to do this film. There is a scene. ... I might be able to make something out of it!’ He was very annoyed. He thought I was wrong! He said, ‘You’re out after the film is halfway over!’ I said, ‘I don’t care how long the part is!’” Rainer had seen Cocteau’s oneact play La Voix Humaine, a monologue of a woman talking on the phone. She imitated it, she said, and instructed Leonard, “Do it in one take.”

When The Great Ziegfeld turned out to be more than four hours long, Mayer famously insisted that Rainer’s “dreary” telephone scene had to go. Stromberg fought to save the scene. It stayed in, and won Rainer her first Academy Award. At the ceremony, held at the Biltmore Hotel, she wore a charming white suit and posed smiling between Paul Muni, who won the best-actor award, for The Story of Louis Pasteur, and Frank Capra, who won as best director, for Mr. Deeds Goes to Town. On the night she accepted the Oscar, she said, she had no sense of what an Academy Award meant. “Darling, in Europe we did not need these accolades. It was a blur to me.” For film critic and author Molly Haskell, “Rainer’s Oscar represented Hollywood rewarding high culture with a capital C. It was a reward for theater art and a sign that Hollywood still did not take itself seriously.” The award, however, allowed Rainer to demand better movies. “I was an enigma to them. They did not know how to handle me. I would say, ‘I don’t care about money.’ And they would say how ‘shrewd’ I was. I didn’t even know what the word ‘shrewd’ meant. It was so crazy!”

Rainer chafed under the studio system; lacking the political skills of Joan Crawford or the grit of Bette Davis, she was soon on a collision course with Mayer. A 1936 Collier’s profile of her, titled “The Girl Who Hates Movies,” reported that her very name caused arguments all over town. She was either “a talented young woman who does as she pleases” or “a shrewd, phony, fake temperamental lady with big eyes and an exaggerated opinion of herself.” Rainer made no secret of her feelings about the movies. “This is not acting,” she told Collier’s, adding that she would love to return to Vienna and her life as a theater star.

Rainer arrived at MGM when it was a feudal system ruled by a despot and nicknamed “Mayer’s-Ganz-Mispochen,” Yiddish for “Mayer’s whole family.” Louis B. Mayer wanted stars to be obedient and docile. Crossing him was like asking to be run out of town. The atmosphere was doggedly provincial. When Hunt Stromberg took Emlyn Williams’s play Night Must Fall to Mayer, the studio chief said, “We make pretty pictures.” (Night Must Fall would become one of the first psychological mystery films.) Rainer’s Mitteleuropa sophistication was protected from Mayer solely by Irving Thalberg.

Mayer appeared baffled by Rainer, who was taken up by the European-exile community and developed friendships with the novelists Thomas Mann and Erich Remarque, the composers George Gershwin and Harold Arlen, the lyricist E. Y. “Yip” Harburg, and the architect Richard Neutra. She criticized Mayer publicly, as if her talent could protect her. “They call me a Frankenstein that will destroy the studio,” she told Modern Screen. “It is more important to me to be a human being than to be an actress.”

On the first morning we are together, I raise the subject of fame. How could Rainer have so easily walked away from what most actresses spend a lifetime trying to achieve? “I was never aware that I was anybody,” she says dramatically. “Do you want to hear what I wrote about this?” she asks. She retreats to her study and emerges with a sheaf of papers from her 240 pages of unpublished memoirs. Softly she begins to read about a dinner which would alter her life. It was the autumn of 1936, and Rainer was at the Brown Derby with George Gershwin and Harold Arlen:

A hush came over the restaurant. Someone had entered. I did not know him. Heads turned. Most others seemed to know him. . . . His eyes came to rest on our table. Slowly he came towards us. He spoke to Gershwin and to Harold Arlen, and they asked him to sit down. I was introduced. “Clifford Odets, our new Chekhov.” I had never heard of him. Tall, well-built, with large gray-green eyes, his light hair brushed back from his high forehead. He somehow reminded one of a disciple. He did not address me with a single word. During conversation and questions concerning his last play, which, as I heard, was the rave of New York’s critics, he answered in a quiet, low voice. I felt strange. What was that? There was something flamelike about this man, attractive, warming, burning as well. As though to protect myself, I moved my chair a little away. And he noticed it and looked at me. Our eyes met.

Two weeks later, Rainer was invited to a party at the home of Dorothy Parker:

Except for Ginger Rogers, most guests were unknown to me. On the far side of the room, surrounded by people who seemed to lap up his words, stood Clifford Odets. Over the crowd I felt him looking at me. I left early: I had to be up at six o’clock in the morning to get to the studio by seven A.M. . . . A few days later while on location, I was called to the telephone. It was a man’s voice: Clifford Odets. “Can one ever see you alone?” he asked. Two evenings later he collected me and took me out to dinner. We went to a restaurant at the end of the long Santa Monica pier. Afterwards we went for a walk along the beach. To my horror, it was littered with lifeless fish. Something in the water had poisoned them. I trembled. Clifford Odets took me back to my house. That night started for me the wildest, the most compelling and frenetic, the most tragic relationship. It changed the flight and rhythm of my life.

Rainer stops and looks up. “You see,” she says, “I used to fly. I had wings inside. And suddenly I could no longer fly.”

Brilliant and tormented, the creator of an American theater of protest, the Philadelphia-born Clifford Odets would soon be on the cover of Time. Awake and Sing! and Waiting for Lefty had brought a new vocabulary of realism to the stage. They were performed by the Group Theatre, a New York company devoted to the acting method of Stanislavski, whose members included Harold Clurman, Elia Kazan, Lee J. Cobb, and Stella Adler. In the summer, the Group would adjourn to Lake Grove in upstate New York to work on its next season. Like many of the young intellectuals of the era, some of them were strongly left-wing, sympathetic to the Loyalists fighting in the Spanish Civil War. Later, in August 1940, along with Humphrey Bogart and Franchot Tone, Rainer would be interviewed by Martin Dies Jr., who was conducting a witch-hunt for Hollywood Communists.

When Rainer talks about her threeyear marriage to Odets, she quotes Oscar Wilde: “Each man kills the thing he loves.” “He devoured me,” she says. Rainer calls Odets “the passion of my life,” but she says he was constantly tom between his commitment to the Group and his desire for intimacy.

At one point, she brings out a binder filled with hundreds of Odets’s letters to her. They are carefully preserved, each page in a plastic cover. Because Odets was forced to remain in New York for much of their courtship and subsequent marriage, his letters were prolix, discursive, filled with longing and dread. He sometimes wrote three times a day. Of a weekend they spent together, he wrote,

very good, nourishing, and I . . . [am] better and happier than I’ve been for a long time. ... It would be terrible if something happened, if in the end we went different ways. ... I give you Beethoven’s Seventh because it is most like what I feel for you, not forgetting the slow movement. How terrible and wonderful this feeling. . . . How wonderful our last night together.

Odets’s passion for Rainer intrigued the press and nettled Odets’s Group Theatre comrades. He was their leftist hero, son of a Jewish printer from the Bronx, all hard edges and nasal accent, and he was dazzled by Rainer’s beauty and delicate grand bourgeois manners. “Clifford was a poet,” Rainer says. She did not disguise her resentment of director Harold Clurman’s influence over Odets, which resembled Mayer’s domination of her. She told Odets that Clurman was “fattening on him,” according to Odets’s biographer Margaret BrenmanGibson, and 60 years later Rainer still says Clurman “behaved very badly. He was very possessive of Odets, and I was of course in the way.”

She was filming The Good Earth during the first months of their romance, and the production appeared “jinxed and interminable,” according to Brenman-Gibson. It took years to complete. George Hill, the first director, committed suicide; the next director, Victor Fleming, fell ill. Sidney Franklin, who finished the picture, and Irving Thalberg had to pacify Chiang Kaishek, who thought the film would concentrate on the suffering in China.

Rainer again fought her bosses. “The makeup man wanted to make a complete mask.” She insisted on playing the part with almost no makeup. “I became Chinese,” she says. “I came one day when they tested people for mass scenes. There were many Chinese people—cooks, waiters, servants. . . . And my pocketbook under my arm fell. As I bent down, one of the little Chinese women also bent down. Our heads hit, and she looked at me. . . . She was O-Lan.”

The scale of the production was immense; Franklin orchestrated swarms of peasants, a revolution, even a plague of locusts. Paul Muni’s wife sat on the set every day in a deck chair, Rainer recalls peevishly, instructing the cameraman on the best angles for Rainer’s co-star. Rainer’s performance was a tour de force. “What is revolution?” O-Lan asks during a famine, then answers herself, “A revolution makes food.” Ironically, the strongwilled Rainer was lauded twice for performances in which she walked two steps behind a powerful husband. In the front office, meanwhile, Mayer feuded with Thalberg, her champion, over the making of quality movies.

Odets wept when he learned in September 1936 of Thalberg’s sudden death at 37 from pneumonia, for he identified with the creative genius cut down by Philistines. He wrote to Luise:

To have a harrowing sense of what can happen to anyone . . . well, it sickens one at the heart. . . . For what is work and effort without a friend, a lover, a mother and father and brother and sister all rolled into one? Darling, let me be all those things for you (and you for me). . . . For the present, Luise, I send you my softest, most tender self and the strength of my arms and mouth, all of which are very much in love with you.

For Rainer, the death of Thalberg, her protector, was ominous. Mayer now turned against all executives with “highbrow interests.” He was furious that it was too late to recut The Good Earth into one of his “happy pictures about happy people.” Rainer, trapped in a seven-year contract, could not control her resentment. She wrote Odets that she felt like “a bolt in their machinery.” She would be destroyed as an artist if she had no say in the choice of script or director. In one letter, Odets advised her to calm down, and he took her to task for treating her agent, Myron Selznick, with disdain. “I urge you to let Selznick work for you and to make him feel that you respect him as an agent,” he wrote.

Nervous about marriage to the highstrung Rainer, Odets consulted a famous graphologist, Lucia Eastman, using false names to camouflage their identities, according to biographer Brenman-Gibson, who found the reports in his files. The young woman, Eastman wrote of Luise, was charming but had had some “deep hurt in her youthful days.” She was mistrustful and had an “inverted vanity.” A marriage would have to be “properly managed,” because “Mr. Von Delf,” as Odets had called himself, was “still very much of the small boy—sensitive and imaginative.” He would need her to be both “wife and mother. . . . She will [have] to remember that a hurt child is often apt to try to hurt the mother he loves.”

The Odets-Clurman relationship, stormy and intense at best, was strained by the news of Odets’s upcoming marriage. Clurman did not want the playwright’s attention siphoned away from the Group. Odets ignored Clurman and went ahead with the marriage. Thoughtless and selfobsessed, he presented Rainer with nightgowns that would have fit a woman twice her size. The January 1937 ceremony at Luise’s Brentwood house was interrupted when a swarm of photographers rushed through the door. The couple took off for a hotel in Ensenada, depressing ly empty in the off-season except for a group of midgets. Odets stuck to his work schedule-midnight to dawn. “I was alone with the dwarfs downstairs,” Luise said.

On the beach the next morning, Rainer saw Odets walking alone. She rushed to him to jump into his arms. “He moved away,” she said. Luise soon began to see a pattern in his behavior. Later she would tell Anais Nin:

He was always abandoning me. He used to leave at night after we made love, when I wanted him to sleep with me. When I was in Hollywood, he would come from New York with a small valise, and I would look first of all at the small valise and think, He is already planning not to stay long. And I felt deserted as soon as he arrived.

Rainer’s life became defined by intense work and the strain of a difficult marriage. “I made eight films in three and a half years, and in the same period I had to shoot The Great Waltz twice, because Louis B. Mayer did not like the director’s first cut. ... I would come home exhausted, change into something pretty, and have dinner with Clifford, who usually just wanted to be with me alone.”

Rainer grew to detest Harold Clurman and then actor Elia Kazan, who, among others from the Group, would stay for weeks with the newlyweds in Los Angeles, working on Group Theatre productions. “It was terrible,” she recalled. “They would eat everything and drink everything. I used to have to walk in the hills to get away from them.” They could be boorish and rude. Kazan saw the opening of The Good Earth, and Rainer was anxious to hear what he thought. “He never mentioned it to me,” she said.

In February 1938, she was nominated for best actress, as was Greta Garbo for Camille, and Garbo was favored to win. Driving back to Los Angeles on Oscar night following a two-week holiday with Odets in San Francisco, Rainer called home from Santa Barbara. “My maid was frantic. ‘Miss Rainer, Miss Rainer, you must come immediately! The newspapers are calling. Tonight is the Academy Awards. They expect you there!’” Rainer had a quarrel with Odets, who was jealous of the attention she was receiving, and wanted to attend the ceremony alone. “He wanted to go with me, but I didn’t want him to come,” she said. “He made me so unhappy. He made me cry all of the time.” Rainer rushed home to change. Then, still arguing, they circled the Biltmore Hotel three times before she dashed in to accept her award. The story has become part of Hollywood Oscar lore.

Despite her two Academy Awards, Rainer was mired in a sinkhole of despair. “Mayer used to say to us, ‘Just give me a good looker and I will make her an actress.’” Once, gazing out her dressingroom window, Rainer saw Greta Garbo walking alone toward her set. “Ah, she’s getting old,” an MGM producer said to Luise. At the time, Garbo was 30.

Odets’s obsession with his wife could also be unnerving; he often wrote down her remarks. “He once said a terrible thing. He said, ‘Darling, if ever you want to commit suicide, do it in my arms.’ If I had been dead, he would have had me forever. ... I was like a slave with him, and yet he never had me.”

The fights with Odets became increasingly frequent. Once, after a Sunday buffet, according to Neal Gabler’s book An Empire of Their Own: How the Jews Invented Hollywood, Odets screamed at Rainer because she had not hired servants to wait on the table. In Hollywood one had servants, the leftist playwright told his wife; otherwise why come here? When he was angry, he was monstrous, Rainer recalled. “The biggest thing was he used to say, ‘Your instinct stinks.’” Forced by the studio to make one bad movie after another, Rainer could not get away—in her life or her career—from the role of the long-suffering victim. “They used to say, ‘She can play a Chinese peasant or Ziegfeld’s wife, so she is hard to cast,’” Rainer said. MGM forced her into such B movies as The Emperor’s Candlesticks, Dramatic School, and The Toy Wife, a bathetic drama in which she plays Frou Frou, a coquette disregarded by her conventional husband, played by Melvyn Douglas.

As Rainer lobbied for better scripts, she was unaware of a crisis in the film industry. Movie grosses slumped during the recession of 1938. WAKE UP! HOLLYWOOD PRODUCERS read a full-page advertisement in The Hollywood Reporter that spring. “Practically all of the major studios are burdened with stars—whose public appeal is negligible.” As theater owners pressured the studios to stop turning out prestige films, which made little money, Greta Garbo, Katharine Hepburn, and Marlene Dietrich were labeled boxoffice poison. The theater owners demanded lighter fare—Westerns, Charlie Chan movies, Andy Hardy.

In May 1938, Rainer discovered that she was pregnant. When Odets received the news coldly, Luise made another fast decision. “This love was so incredible. And I aborted his child. But it was his fault. Because he was terrible. ... I knew it was not possible. He would have killed me.” Later, Margaret Brenman-Gibson would discover in Odets’s papers a wire he never sent to Luise. In it, he expressed pleasure at the news of the coming baby and urged her to run away from Metro and live with him in the country, where they could raise their child. Rainer told the biographer sadly that if she had received that telegram she would have done exactly that.

Odets would fly into rages at Rainer, breaking furniture and, once, “every plate in the house.” Rainer recalled feeling “constantly diminished,” as she had with her father. “Clifford would say, ‘You want sugar, sugar, sugar all the time!’” she said. “Look at this picture,” Rainer told me one day in London. “This was the story of our marriage.” The photograph was startling. In it Rainer was surrounded by photographers. In the background Odets looked dazed and unhappy. “He was so jealous,” she said.

In the summer of 1938, Odets left for Lake Grove with the Group to work on Rocket to the Moon. They were despondent, according to another Odets biographer, Gabriel Miller. The Group’s finances were faltering, and they were three years from disbanding. Drinking heavily, Odets began a wildly romantic affair with the blonde actress Frances Farmer, who had been in his play Golden Boy. Later their relationship—including his throwing rose petals on the bed before they made love for the first time— would be portrayed by Jessica Lange and Jeffrey DeMunn in the 1982 film Frances.

“Nineteen thirty-eight was very, very hard,” Rainer said. “In my private life, devastating. I was exhausted.” Separated from Odets for five months, under pressure at the studio, Rainer vented her rage on her makeup woman, saying, “I don’t want to make films anymore. I don’t want to see this camera anymore. I can’t stand myself on the screen! I don’t want it anymore!” Soon after, she was summoned to Mayer’s office. He was furious at her for her disloyalty, but he might have been placated by a display of humility. It was not to be. “Mr. Mayer, I cannot work anymore. It simply is that my source has dried out. I have to go away. I have to rest.”

Rainer recalled his icy response: “What do you need a source for? Don’t you have a director?” At the core of their famous argument was a clash not only of temperaments but also of class resentments. Mayer, the vulgar Eastern European, needed to dominate the snobbish German star. “If you can’t release me from my contract, at least give me a leave of absence,” she said.

“Luise, we’ve made you, and we’re going to kill you,” he said.

That moment, Rainer’s career changed forever. She would not humble herself. “Mr. Mayer, you did not buy a cat in the sack. ... I was already a star on the stage before I came here. I shall tell you something. All of your great actresses in this country are between their early 40s and 50s—Katharine Cornell, Helen Hayes, Gertrude Lawrence, Laurette Taylor. I am in my mid-20s. ... In 20 years you will be dead. That is when I am starting to live!”

They never spoke again.

Breaking her contract, Rainer left Hollywood to rejoin Odets in New York. LUISE RAINER AND CLIFFORD ODETS RECONCILED AND SHE WANTS WORLD TOLD IN BIG HEADLINES, one paper bannered. It did not last. There was constant jockeying for power, which created an inexorable tension between them. Rainer wanted “security and peace,” and Odets could never provide them. Increasingly sensitive to the coming war, Rainer was soon caught up in the terrible events in Europe. She had long since reconciled with her parents, but she could not get them to leave Hamburg. When Jewish neighborhoods were destroyed by Nazi storm troopers during Kristallnacht (“night of the broken glass”), she wired her husband: “Am sick over happenings in Germany. Many friends . . . newly imprisoned.” She begged him in a letter to write “a new anti-Nazi play.” By then Rainer had brought her two brothers to America, but, she recalled, “my father was impossible” and for months he refused to move to Brussels.

Earlier, in 1937, Albert Einstein had received Rainer and Odets at a rented cottage in Peconic, Long Island. Rainer asked him to help rescue European refugees. A famous photograph was taken of them in a rowboat on Long Island Sound. Rainer wore her trademark white pants. “He was very normal,” she said of Einstein. “He played the violin and did not talk about the Theory of Relativity.” Odets became so jealous as a result of Einstein’s attention to Rainer that he later cut off the scientist’s head in the photograph of them together.

Rainer and Odets lived in Greenwich Village, at One University Place. He insisted that she be a hausfrau, deferring to his need to write with music playing at full volume and keeping the refrigerator stocked with his favorite foods. She sometimes took refuge at the Waldorf or with friends. She confided in the photographer Alfred Stieglitz, who wrote her long romantic letters. The fights with Odets became more and more violent. Once, she said, “we were walking along Fifth Avenue, and he was screaming at me. We went into a taxi, and he was screaming. At one point the taxi stopped, and he got out of the taxi, and the driver looked at me and said, ‘Get rid of that bastard.’”

In 1939, after two years of marriage, Rainer wrote her husband a sad farewell letter. “So many beautiful words had come all ready from you, so little had been done to realize them, and horrible words . . . and you didn’t realize what you had said or done and were surprised or disturbed when I was broken into pieces.”

When she left Odets, she told me, “he tried to kill himself. He went to Mexico and he ran into a tree! It was all crazy. . . . I just left! . . . Probably if he had said something, he would have said, ‘Go!’ ”

In her London apartment, Rainer has a highly organized filing system. There are drawers full of meticulously preserved papers and a master list that reads “People Who Have Corresponded with Luise Rainer.” These include Pearl Buck, Bertolt Brecht, Eleanora Duse, Chiang Kaishek, George Gershwin, Lillian Heilman, Luchino Visconti, Vivien Leigh, Tennessee Williams, Lotte Lenya, and Alfred Stieglitz. In the rare interviews she has given over the past 60 years, Rainer spends most of the time describing a period that was over by the end of World War II, when she was only 35. A year after Odets’s death, in 1963, she recalled him in her memoirs: “His lack of ever relying on anything but himself was the source of his restlessness and selfdestruction.”

While Odets was carrying on with Frances Farmer, Rainer fell in love with a British aristocrat. She stayed in England for a year and appeared in a West End production of a romantic comedy, Behold the Bride. Jealous and possessive, Odets broke off with Farmer in an attempt to win his wife back. When the Germans marched into Paris, Rainer learned that her father had been arrested in Brussels and sent to a camp as a political enemy of the Reich. Frantic, she approached William Bullitt, the U.S. ambassador to France, to pressure the State Department into rescuing him. Near death from starvation when he was released, Henry Rainer then had to cross the Pyrenees on foot. His arrival in New York was noted in the press. Luise was described as looking wan and exhausted, as if the complexities of her life had suddenly overwhelmed her. Rainer and Odets tried unsuccessfully to reconcile one more time after their divorce in 1940. Soon after that, Rainer discovered Odets with a young actress, Bette Grayson, whom he had met through Harold Clurman.

She made one more movie in Hollywood, for Paramount. The film was Hostages, a 1943 wartime melodrama, which she once told an interviewer had been such “a horrendous experience” that she had never seen it. She returned to New York to sell war bonds and then toured Europe for Mrs. Roosevelt. By then Mayer had blacklisted her. Rainer wanted the role of Maria in Sam Wood’s For Whom the Bell Tolls opposite Gary Cooper, but she was never asked to audition, and the part went to Ingrid Bergman. Bertolt Brecht approached her and said, “I must write a play for you.” She suggested an adaptation of A. H. Klabund’s novel The Chalk Circle. She even went to a close friend who was a producer and had him bankroll the playwright. Months later, Brecht had written only two pages of what would ultimately become The Caucasian Chalk Circle, one of his plays with Chinese settings. Rainer recalls, “I told him I thought his behavior was outrageous!” To which Brecht replied, “Another actress would be on her knees to play this part.” Rainer said angrily, “I don’t want anything more to do with you.”

Near the end of the war, at a party in Manhattan, Rainer met a handsome young Swiss publishing executive, Robert Knittel, who worked in New York. The son of the wealthy Swiss novelist John Knittel, Robert had wintered in Egypt as a child and shared Luise’s love of music and the cerebral life. “I am going to marry her,” he said to a friend at the party. Then each morning on his way to work he would push a love poem under her door at the Plaza. “He worshiped her,” their daughter, Francesca Bowyer, says. Knittel was quietly uxorious. “Cliff was my passion. Robert was my home,” Rainer says. By then Odets had married Bette Grayson, with whom he would have two children.

After their marriage in 1945, Rainer and Knittel lived in a town house on Sutton Place and later in an 18th-century farmhouse in North Stamford, Connecticut. By 1956 she had moved to London, where Knittel worked at the publishing firm Jonathan Cape. He later became the editorial director at William Collins. After Knittel retired in 1979, the couple moved to Vico Morcote, a village outside Lugano in Switzerland, where Rainer painted and worked on her memoirs until his death in 1989.

Back in London since 1992, Rainer is indefatigable—out four nights a week with a circle of friends that includes the writer Jill Robinson, daughter of producerdirector Dore Schary. “I have so much energy,” Rainer says, “it is fabulous.” She travels often to New York and Los Angeles to visit her daughter. Money has never been an issue with her. “I never spent my money on myself,” she says. “I surrounded myself with beautiful things.”

One afternoon after lunch, Rainer turns to me. “I am a little bit tired,” she says. “Come with me to my bedroom, and we will both lie down. I will close my eyes, and then you can continue the psychoanalysis.” I follow her to her airy pink bedroom, which is filled with photographs of her daughter, Francesca, who resembles Ali MacGraw, and her two beautiful granddaughters. One is married, the other attends Southern Methodist University in Dallas.

Rainer arranges herself on the pillows and closes her eyes. “You may continue,” she says softly. “What can it mean to be an artist of your gifts and not have done serious, meaningful work for the last 50 years?” I ask. Rainer suddenly leaps up on the bed and exclaims, “I am a great talent, yes! ... I would say it is my greatest achievement to have come out of that. ... It would be a lie to say that I did not think much of myself! Because I thought enough of myself. I would have loved to give out! . . . One wants to be the best one can be, and I suppressed it!” Her voice fills the room, tears well in her eyes, and for once there is no performance. “I lived like a nun!” she says sadly. Later she says, “It was me who withdrew. I got a reputation that I did not want to work. And I did not counteract that.”

Occasionally, in the dead of night, she would cry to Robert about the loss of her career. From time to time there were offers, but Rainer’s energies had shifted; she had grown tired of “the baloney and nonsense,” as she called it. She retreated into the pleasures of a happy marriage; she painted, made collages, and lived beautifully in London, in a large house in Eaton Mews. Rainer appeared occasionally in the theater, in New York in 1952 in The Lady from the Sea and later in The Little Foxes in Vienna, but she was often impatient and querulous. She insisted on having her career on her terms, however rarefied. In 1983 she toured the United States in a one-woman performance of Alfred Tennyson’s 900line poem, “Enoch Arden.” She refused to compromise, routinely taking refuge in her family life.

In 1958, when Federico Fellini was planning La Dolce Vita, he approached Rainer and said, “I need your poetic face!” He sent her an early script, which she told him was “absolutely terrible! . . . Pure nonsense!” She was to play a single scene, opposite Marcello Mastroianni, a comeback that could have revived her movie career. Mastroianni plays a foolish Lothario, and Rainer would have none of it. She insisted on rewriting their scene. During that torrid summer in Rome, she and Fellini argued. “I love what you wrote,” Fellini said, “but you must fuck Marcello Mastroianni!” Rainer responded, “I want to go back home to my husband! I do not want to sweat my summer away! We must talk about my scene.” They reached an impasse, and Rainer said she would do it her way or not at all. She recalls, “Fellini got down on his knees and said, ‘You cannot leave!’ and I said, ‘Leave me alone!”’ Later she sued the production company, holding up La Dolce Vita’s release until she was paid.

At the end of our interviews, I discovered an oddity. I was on the telephone with Francesca, and the subject of her mother’s religion came up. “I did not know she was Jewish. Do you know something I don’t know?” her daughter said lightly. Although she had read her mother’s memoirs, she insisted that she had no idea her grandfather had been in a camp. “You did not know that your mother was listed as a prominent Jewish actress in the Encyclopaedia JudaicaT’ I asked. “Really?” Francesca said. Later she said, “There were a lot of people who were in concentration camps who weren’t Jewish.”

I experienced a similar moment when I interviewed one of Rainer’s closest friends of 40 years, Ingeborg ten Haeff, an artist who lives in New York. “I didn’t know,” she said when speaking of Luise’s Jewish heritage.

Two days later, Rainer called me from London. “Why are you tormenting Francesca?” she asked playfully. “I’ve been thinking about your obsession. It’s mad, racist. It’s just as racist as how Hitler felt about being Aryan. I personally do not believe in religion. It’s a man-made formula.” I asked Rainer to explain this conundrum: How can she be so candid about her life that she appears in the Encyclopaedia Judaica, yet with her daughter and her close friend she leaves out key facts? During our talks, Rainer had alluded to a drama that undercut her marriage to Robert Knittel, but had dismissed it with, “Once again, it is a big story.” On the telephone she chose again to be vague, saying, “Why should I burden my child?”

She finally explained. Before meeting her, Robert Knittel had attended Oxford and the University of Virginia. He was eager to volunteer for the Royal Air Force, but as a Swiss citizen he was not legally allowed to join. Knittel’s parents remained in Switzerland during the war, and when Robert and Luise got married, he phoned to tell them the news. His mother responded negatively in a letter: “We read about Luise Rainer, and if she had to leave Austria for political reasons, it would be the death of your father.” The euphemism “political reasons” clearly implied Rainer’s Jewish heritage. Although Rainer had been reared in a family that used the word “Jewish” in whispers, she was outraged at this insult. To her horror, she came to realize that her in-laws were Nazi sympathizers. The hostility was palpable. “One day I was taking a bath, and my mother-in-law walked in and saw me naked,” Rainer told me. “She said, ‘The family has different breasts from you.’ ”

“When Francesca was 10 weeks old, Robert, the nurse, and I and the baby left for Switzerland to visit,” she told me. “My nurse came to me one day and said, ‘Mrs. Knittel, I was walking behind your mother-in-law and I heard her say to your father-in-law, ‘Luise thinks you are a Nazi.’ It was like suddenly being at Berchtesgaden, in Hitler’s country retreat.” However ambivalent she may have been about her own background, she now told Robert that she wanted a divorce. “I cannot come between the man I love and his family,” she told him.

She moved into the Savoy in London. “Robert was miserable,” she said. They soon reconciled, but Rainer did not see her mother-in-law until shortly before she died. When news of John Knittel’s sympathies leaked out after the war, his popularity as a writer waned in Switzerland. Rainer’s mother-in-law asked her to appear with him at interviews. “I would not do it,” Rainer said. However much she despised her husband’s family, she made a decision: Francesca would be shielded at all costs. “I’ve written it all down for her, what really happened, and someday she will read it,” Rainer told me.

On our last afternoon together, Rainer returned the conversation to the essential fact of her life. “Look, darling, I’ll tell you something. As you look around at other actresses who are [still] working now, are any as healthy as I am?” She stood and made a tiny bow. “And, darling, look at me!”

From Africa, Rainer sent me a joyous postcard describing a night she had spent in the bush under the stars, after a long train ride from Cape Town to Victoria Falls. Back in London, she telephoned and, her voice brimming, read me a description of her trip. “The horizon so very far, the sky unending, floating clouds, higher, higher, more voluminous than I have ever seen ... no artifice.” She hesitated. “Darling love, you just don’t know the beauty of it.”

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now