Sign In to Your Account

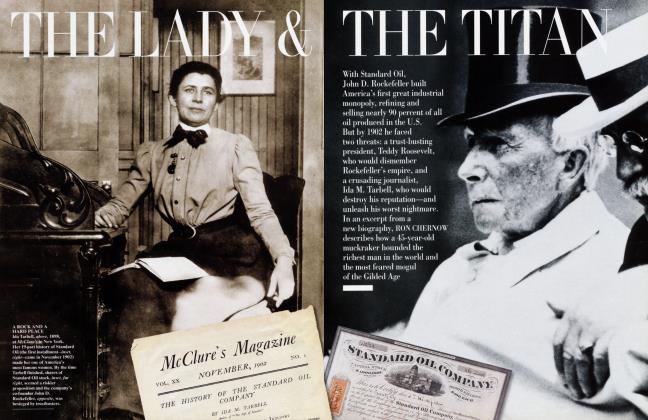

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

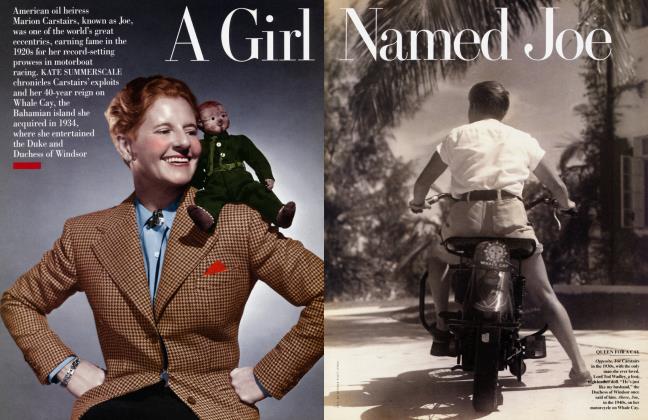

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowGONE WITH THE GYPSIES

In 1993, San Francisco private eye Fay Faron discovered that a beautiful Gypsy and her family appeared to be involved in a string of Arsenic and Old Lace-style murders. Then Faron had to prove it before more men died

JACK OLSEN

The caskets came out of the earth like bad teeth. The crew worked fast to avoid unwanted attention—relatives of the deceased hadn't given permission for the bodies to be exhumed. One casket cracked in half, revealing a body that had steeped like a tea bag in groundwater. A sturdier coffin preserved a set of bones nattily attired in a dark-blue polyester suit. Another cadaver had jelled: old man in aspic. The fourth body rested in a cheap, clothcovered wooden box, the yellowing bones draped in a hospital gown. A plastic ID bracelet was dangling from what had been a wrist.

At least one person was enjoying the grisly operation: Fay Faron, proprietor of the Rat Dog Dick Detective Agency. (The agency's name had been inspired by an early client, who had commented that Faron tracked down missing persons like a rat dog finds rats.) At last, in April 1994, after a year and a half of pro bono work by Faron, and a saga of bureaucratic bungling by the police that had lasted almost as long, one of the private detective's most frustrating cases seemed headed for prosecution. The bodies had all belonged to old men, but the way Faron saw it, they hadn't died natural deaths. She believed they had been poisoned by Gypsies. Now what remained of their vital organs was to be removed and tested.

Then in her early 40s, Faron was an attractive woman whose head was crowned with a set of Orphan Annie ringlets, which spilled from under her slouch hat to the collar of her trademark plum trench coat. She was well known as the author of an advice column, "Ask Rat Dog," syndicated in many newspapers, including The Denver Post and The Dallas Morning News, but most of her income came from locating hidden assets and people other people wanted to find. She had stumbled into the detective business in 1983 after failing to find success as a door-to-door sewing-machine peddler, a bike-tour leader, a waitress, an ice-cream-truck driver, and a TV producer.

The alleged geriatric-poisoning cases had reached her desk in late 1992 in a roundabout way. An obese 35year-old Gypsy named Danny Bimbo Tene had become involved with a Russian-born woman, 53 years his senior, Hope Victoria Beesley, who had immigrated to San Francisco after spending part of World War II in a Japanese prison camp. By all accounts, they made an odd couple—the coarse young Gypsy and the sophisticated world traveler. What on earth did she see in him? most people wondered.

Hope Beesley said she was receiving anonymous phone inquiries as to whether she was dead yet.

Whatever it was, it didn't last long. After they broke up, Beesley told a lawyer that Tene was a liar, a cheat, and a crook, and claimed that she'd spent a year trying to get his name off a jointtenancy agreement that she said he had persuaded her to sign. Now Tene was, in effect, half-owner of Beesley's fivebedroom house in San Francisco's Sunset district. When she died, he would become the sole owner. The old woman insisted that her demise was already in the planning stages; she said she was receiving anonymous phone inquiries as to whether she was dead yet.

Her lawyer retained Fay Faron, who was on the case only a week when word came that Beesley had suffered a fatal heart attack. Danny Tene moved into the home, valued at $373,000. For Faron the case was officially closed because there was no client.

But the detective was so unsettled by the elderly woman's sudden death that she went to city hall to do some research on Danny Tene. In public records she found an abundance of entries under the name Tene: eviction cases, lawsuits, a baby who had died mysteriously, a Tene killed in a parking lot. Faron uncovered what she believed was a transcontinental scam that went back at least a decade. It involved attractive Gypsy women cuddling up to octoand nonagenarians and separating them from their stocks, homes, and bank accounts. (Danny Tene had apparently come up with the idea of reversing the sexes.) The alleged female perpetrators were close relatives of Tene's, members of the same Tene Bimbo clan featured in Peter Maas's bestselling 1975 book, King of the Gypsies. No one knew exactly when this particular branch of the peripatetic Tene Bimbo clan had joined San Francisco's estimated 4,000 other Gypsies—after earlier residencies in New York, Boston, and Chicago—but it appeared to have been sometime in the mid-70s.

The name Bimbo was derived from bimbai, the Gypsy word for "tough guy," and the Tene Bimbos tended to be not only resilient but also reclusive, contemptuous of gadje (non-Gypsies, literally "serfs"), and unpopular with other Gypsy clans, most of whom were profoundly nonviolent.

Faron discovered that every Gypsy has at least three names: a secret one whispered once by the mother at birth, a Gypsy name, and a name to be used in dealing with the gadje. Some of the Tene Bimbos had many more names than that, however. The matriarch of the branch that Danny Tene came from was Mary Tene, who also went by Bessie Tene Bimbo and Mary Steiner. An eighth-grade dropout, she and her common-law husband, Stanley Tene Bimbo, also known as Richard or Chuchi, were parents of six children, the eldest of whom was Danny. Her Gypsy husband notwithstanding, Mary had met and married a well-heeled, retired construction engineer, Philip Henry Steiner Jr., in 1983. At the time, she was 43. He was 89.

Theresa Tene, Mary's eldest daughter, had inherited her mother's taste for superannuated males with bulging portfolios. An ivory-skinned teenager, she had dazzling blue-green eyes (which she accentuated with heavy makeup), curly dark-brown hair, a pert nose, and a Pamela Lee silhouette. In August 1984 she met 87-year-old Nicholas Bufford, a childless Russian immigrant and retired hotel worker. A month later she described herself on a legal document as the widower's granddaughter, and signed on as joint tenant of his $226,000 Sunset-district home. That month, they were wed. A corrected deed noted that she was his wife, not his granddaughter.

The marriage was barely two months old when an emaciated Nick Bufford was observed by friends; he subsequently died. The beautiful young widow, now calling herself Angela Bufford, inherited her husband's house and $125,000.

A bit later, her mother, Mary (whose legal and Gypsy husbands were still alive), became friendly with another Russian widower, Konstantin Konstantinovich Liotweizen, when he was in the hospital with a broken hip. Born in 1897, he had been decorated by Tsar Nicholas II for service in the Imperial Army, and forced into exile during the Russian Revolution. Before retiring, the sturdy ex-officer had run the Russian Food Store and other San Francisco delicatessens, and had become an admired figure in the city's Russian emigre community—"the grandfather I never had," as one neighbor described him. He rented out the dozen units in the Richmond apartment building he owned for modest amounts to artists.

When a friend arrived at Liotweizen's door to bring him a cake in the winter of 1986, she was greeted by Mary Steiner in a white nurse's uniform. Mary explained to visitors that she enjoyed caring for the elderly and soon moved a flock of her relatives, including Danny, into one of Liotweizen's empty apartments.

One day a longtime tenant and friend of Liotweizen's heard an insistent banging on the pipes and checked to see if it was a call for help. Mary claimed that her patient was fine, but when she left the building, the tenant slipped into the apartment and found the tsar's ex-officer lying in his own excrement next to a mildewed slice of pizza and a glass of curdled milk.

"It's too late for me," Konstantin Liotweizen said. "She's caught me like a little baby bird."

"It's too late for me," he said weakly. "She's caught me like a little baby bird."

By the time police came to check out the situation, the old soldier had been cleaned up, fed, and cosseted into a better mood. Then Mary changed his phone number, canceled his newspaper subscriptions, and told neighbors that he could no longer attend church.

In April 1987, Mary interrupted her nursing duties for Liotweizen long enough to bury her husband, Philip, dead at 93. Mary's close supervision of her husband's health and well-being was demonstrated later in questioning at eviction proceedings she had instituted against one of her tenants:

Q: How did Mr. Steiner die, ma'am?

A: I don't remember. ... He had a heart attack or something like that.

Konstantin Konstantinovich Liotweizen hung on for two more years, finally expiring due to arteriosclerosis and cardiac arrest—more or less generic entries on the death certificates of unautopsied old men. Mary became the sole owner of his apartment building, valued at $937,440 by the assessor. Although a friend reported that Liotweizen had kept some $500,000 in banks, only $77,000 turned up in his accounts.

While the new landlady busied herself raising rents, frightening tenants into leaving, and, when all else failed, serving eviction notices, her daughter Angela found a new boyfriend: George Antone Lama, a 30-year-old Palestinian who was helping his emigre family run a restaurant in West Portal called the French Village Deli. Over her family's shrill complaints about racial treason, Angela installed the gadjo in the home she'd inherited from Bufford. She worked a day job as a teller at the Security Pacific Bank while continuing her charity work with the elderly in the evenings. Soon she'd insinuated herself into the life of a woman who lived in the opulent, old-money neighborhood of St. Francis Woods, and onto the deed of her $850,000 mansion. But when she brought the millionaire owner to a law office to sign a new will, an attorney concluded that the old woman was incompetent, canceled the proceedings, and tipped off the woman's daughter. Eventually Angela agreed to sign a document confirming that the joint-tenancy agreement had been made improvidently, incorrectly, and in error.

"My mother cried many tears," the old woman's angry daughter told a reporter, because suddenly Angela did not want to stay with her anymore. "Mom just adored her."

Angela's new boyfriend, George, seemed to have no trouble adaptM ing to her unusual avocation. He reportedly confided to his older brother, Jerry, that it didn't disturb him that his girlfriend bared her breasts to sexstarved old clients. "What do you think they're capable of doing at 85 years old?" Jerry quoted his bespectacled, studious-looking brother as saying. "They feel her, touch her, play with her. They're happy, she's happy. It's just business."

Gypsy women have always been easygoing about their torsos (in his poem "Gypsies Traveling" Baudelaire celebrated "their ever ready treasure of pendent breasts"). But they are demure about their thighs and legs. They go braless without regard to the current fashion but wear skirts below the knee. In Gypsy culture, marime is a powerful concept that means impure, polluted, shameful, and the waistline demarcates the beginning of the forbidden zone.

According to police, in August 1989 Angela was fired from her teller job after she cashed a $10,000 check for George, who'd walked up to her window disguised as a laborer and showed false ID. Jerry Lama explained later that George "got her the job at the bank so she could pick victims, see old people coming in and out, and have access to their accounts. They drained the hell outta the A.T.M. machines. George is a master forger, so she would make copies of signature cards at the bank, and he would write checks and take them to her as teller."

The industrious couple had another close call, this time with a Norwegian immigrant named Stephen Storvick. A retired longshoreman in his late 80s, Storvick, like most of their alleged targets, lived alone and unprotected. He happened into the French Village Deli one day and became friendly with George.

Soon Angela was visiting Storvick, running his errands, and escorting him to the movies. He changed his will, naming her as beneficiary. Then Storvick moved into the apartment above the French Village Deli, and George began delivering hot dishes to his door.

Roland Dabai, George Lama's 21year-old nephew and an employee at the deli, claimed he saw George "grind up tablets of this Halcyon and put it in food that George made for Storvick." According to a police affidavit,

George used to brag to Roland about how the drug used to make Storvick dizzy and disoriented. . . . Originally, George told Roland that he just wanted to keep Storvick disoriented so that George could search through his things and steal from Storvick and play with his accounts . . . [After the old man threatened to move out,] George said to Roland, "I've been working on this guy for a year and a half, he's freaking out, he's going to leave." . . . Roland went on to say that it was at this time that George started changing the drugs. *. . . Roland told us that the new medication that George had obtained and was putting in Storvick's food was a round pill about the size of an aspirin tablet and was orange in color [a known pill form of digitalis]. . . . Roland definitely remembers several conversations that Angela and George had where they both said that they were trying to kill Stephen Storvick.

"What do you think they re capable of doing at 85 years old? They touch her, play with her. They're happy, she's happy. It's just business."

Around this time George had begun procuring digitalis, according to the police. Derived from the leaves of the common purple foxglove {Digitalis purpurea), digitalis is used with cardiac patients to regulate the rate of the heartbeat and to strengthen the heart's contractions, but an overdose can be lethal. A relative of George's told police that he referred to the ground-up pills as "magic salt" and sprinkled it into food that was delivered to certain old men. Over three years, he obtained hundreds of the pills from a pharmacist in exchange for free meals, delivered from the deli, and other favors.

The gritty old Stephen Storvick, despite his disequilibrium, began to suspect that he was marked for death. A police report quoted him as claiming that Angela and George were out for his money, and noted, "When [Storvick] is with Angela, a jogger on different occasions [has] attempted to knock him down on the sidewalk." George reportedly admitted to a relative that he was this jogger, wearing a disguise. A broken hip would have put Storvick at the couple's mercy.

After the old man awoke one morning feeling so stiff that he could hardly get out of bed, he arranged to move to a new apartment and tore up the revised will that named Angela as sole beneficiary. She tracked him down and romanced him again, but once more he shook free of her and George. He died of respiratory failure in August 1992. His modest estate was divided among relatives in Norway.

Fay Faron went from astonishment to outrage as she pieced together this information about the Tenes, mother and daughter, and Angela's boyfriend, George. She began to wonder how much the San Francisco Police Department knew about the operation, and checked in with some of her contacts.

She learned that the Fraud Unit had been tiptoeing around the case for months after receiving an anonymous phone call. The caller had said that Angela Bufford and George Lama had two elderly male clients, for whom they were providing rides, food, and other services. The caller claimed that the two old men were in danger, then hung up.

Faron handed over her thickening files to the authorities. She'd heard good reports about the Fraud Unit's inspector Gregory Ovanessian. San Francisco's Gypsies referred to him as "Jawndari Romano," or Gypsy Cop. Of Armenian descent, the detective was multilingual and had a nodding acquaintance with some of the 13 dialects of Romany, the Gypsies' spoken language, which is rooted in Sanskrit.

As the weeks passed, Faron became puzzled by the apparent lack of any action. When she inquired, she was told that the police Fraud Unit hadn't been able to ascertain the identity of the two current victims, but it was believed that George and Angela delivered food to them every day. To Faron, this was an easy problem to solve. On several mornings she and a colleague videotaped the couple leaving home, Angela taking food to one house and George to another. She ran the addresses, both in the Sunset district, through her computer, made a few phone calls, and learned that the registered owners were two men in their 90s: Harry Glover Hughes, a millionaire investor who liked to stroll to the San Francisco Zoo and snap pictures there, and Richard Nelson, a long-retired accountant. Faron soon discovered that George had already taken a cruise to Mexico courtesy of the harddrinking Hughes, while Angela shared her Gypsy charms with the frail little Nelson, who walked with a cane and sent her checks and billets-doux.

Accompanied by her oversize dog, Beans, who wore dreadlocks and was described by Faron as part Samoyed and part Rastafarian, the private investigator drove over to the Lama-Bufford residence one day at five A.M. in her ancient green Tercel. After wriggling her hands into a pair of canary-colored rubber gloves, she plucked two overstuffed plastic bags from their trash can. Back at her second-floor apartment in the Marina district, she says, she dumped the contents into the kitchen sink and found a scribbled note listing Harry Glover Hughes's bank balances and the annotations "Get $ in credit union both A&G" and "Look for s/d deposit box and gold coins at Citibank."

Faron reported her findings to the police, who sent a detective to visit Hughes. The detective found that Hughes had difficulty remembering exactly where his bank accounts were. "Mr. Hughes told me that he had gold coins in his safe deposit box. ... He told me that the key to his safe deposit box that he normally keeps in his home has been missing for at least a year."

George Lama's brother in-law quoted Angela as saying of an alleged victim, "We are helping him go away faster."

The wealthy old gentleman informed the detective that he seldom ate the takeout food that George and Angela brought him in Styrofoam containers, because it tasted funny. He denied having joint bank accounts with George, but investigators later turned up three, plus information about a $10,000 check the old man had allegedly written to George, apparently under the impression that it was an advance payment to the Internal Revenue Service. He also said he had no memory of buying a Mercedes roadster that was registered in both men's names.

On her next trash run, Faron says, she found more banking information on a torn piece of notebook paper. A notation read, "Unit New England Life Ins Co Boston Mass 02116-3900 policy #0463316," followed by information on gift taxes. Another note said, "Meet me at 6 and we'll go look at the RollsRoyce. The [salesman] is expecting us."

Faron found pieces of mail from the couple's other elderly charge, Richard Nelson, as well as an inventory of his assets and a handwritten note to the old man: "Good morning honey. I was here from 8:30-9:00. You were asleep so I did not want to wake you. They called me to work today. Breakfast is in the oven!! Hope you like it. Love & kisses, Angie." More uneventful weeks passed.

"I'm thinking," Faron recalled later, "These old men are gonna die without ever being questioned by the cops! What's the holdup? And the cops are telling me, 'Well, ya know, people have civil rights. We can't just bust in and interview them.'"

By this time Faron had learned from her police sources that lawmen dreaded tangling with Gypsy criminals. An outlaw Gypsy might have 50 names, a stack of false IDs, and a dozen Social Security cards, none legitimate. "How the hell do you track mercury?" a former deputy sheriff had asked. "You can't. So you chase 'em outta town."

In order to gather evidence from the old men in case they didn't survive, Faron decided to draw up a fake questionnaire labeled "Richmond/Sunset Social Services." Among the questions it asked were: "Are you able to get out?"; "How do you get your food?"; "Do you take medication?"; "Who do you call in case of emergency?"; "What is their relationship to you?"

By this time Faron had developed a visceral aversion to the bubble-cheeked Angela Tene Bufford. Her suspected scams went back a dozen years and struck Faron as vile. By comparison, George Lama seemed a mere lightweight hustler who'd stumbled onto a good thing. Faron took the questionnaire over to Richard Nelson's house, but the old man's door was opened by Angela, smiling and wearing a housecoat.

"I didn't have a plan for this," Faron recalled. "I'm thinking, This woman is a serial murderer. I'm not this brave. So I said, 'Well, I can see Mr. Nelson's being well taken care of,' and started to back away, and Angela follows me outside and tells me how the paperboy didn't throw the paper far enough and poor Mr. Nelson broke his foot going down to get it and maybe we could help out with that. She couldn't have been nicer. A sweet little angel. I thought, No wonder the old men like her."

By the fall of 1993, the Lama family seemed to be disintegrating. Jerry Lama, a small, lithe man with a pungent vocabulary, had known about George's transgressions for years but had kept quiet. "I knew it was wrong from day one, but he's my brother. George's first client was Storvick. He learned the whole fucking scam from Angela, and she learned it from her mother."

The home that Angela had inherited from her late husband was now shared by her and George, who lived in one half, and various members of the Lama family, who lived in the other. George and Jerry's sister, Nicole, it turned out, had made the first anonymous call to the police. In July 1993,

Jerry found three recording devices in the garage ceiling, below the family's living room, and believed that only Angela or George could have placed them there.

"I told the cops everything I'd been told by my brother. I told them I wanted to press charges," Jerry recalled angrily.

"[The cops] talked me out of it! I told Inspector Ovanessian, 'You've been informed about the old men since the end of 1992, and now it's July '93. What the fuck have you done?' He promised me that George and Angela would spend Christmas in jail. What he failed to tell me was which Christmas. [Police Department officials declined to comment on any aspect of the case.]

"Then Angela gives my sister, Nicole, a major beating, and Nicole ends up in the hospital with a concussion. The cops talked her out of filing charges. Then [a cop] made a major pass at [Nicole], and she swore she'd never talk to another San Francisco cop."

Jerry, by now enraged, began interviewing relatives to help flesh out the case against his brother and Angela. Roland Dabai told of being enlisted by his uncle George to steal blank baptismal certificates from the church where he was an altar boy so George could use them to obtain fake driver's licenses; George also supposedly had Roland break the car windshield of a man who was pestering Angela, make harassing phone calls, and deliver food to elderly clients.

A Lama brother-in-law, Nabib Atalla, quoted Angela as saying of an alleged victim, "We are helping him go away faster . . . instead of waiting for God's will." A police affidavit observed, "George told Atalla that he made this burrito for [millionaire Harry Glover] Hughes's lunch and that it contained a drug that would make the old man dizzy and cause his heart to slow down. . . . George told Atalla that he [George] had power of attorney over the old man and could get all of his property when the old man dies."

"I'm thinking, This woman is a serial murderer. I'm not this brave," said Faron.

With this new information, the Lama family figured that the case was at the indictment stage, but they were told by police that the district attorney's office was still insisting on more tangible evidence.

Soon afterward, Jerry Lama and Fay Faron were sipping black coffee together at the private investigator's office. They quickly agreed that the police were frozen in place and someone had to make a move or at least two more old men, Richard Nelson and Harry Glover Hughes, were as good as dead. They contacted Glen Billy, then 51 years old, a social worker, reformed alcoholic, and former street artist. Billy, now handling elderabuse cases for the city, affirmed that he was aware of the Nelson case, but he hadn't been able to get the old man to answer his door. After hearing about the case from Faron and Jerry Lama, Billy was so outraged that he immediately drove to Nelson's house on the pretext of making a welfare check. It was early in October 1993.

"Mr. Nelson?" the social worker said pleasantly at the door, "I'd like to talk to you."

The man's reply was barely audible. "I can't talk to you. ... I feel like I'm gonna die."

"If you're that ill," Billy said, "you really need to talk to me."

The old man appeared uncomfortable. "Can you come back in a couple of days?" he asked. "I'll feel better."

Billy checked with neighbors and learned that they were worried about their friend. A beautiful young woman arrived daily in a BMW 735 and sometimes drove Nelson away. A friend had jotted down the licenseplate number, and Billy found that the luxury car was registered to Angela Bufford.

"I went to the nearest police station," Billy recalled, "and they said, 'Oh, no, we're on top of this, and we would like it if you didn't disturb our investigation.'

"I said, 'Well, I'm very disturbed. This man may be dying.'

"The sergeant said, 'We'll get on it.'"

A few days later Billy found himself sit ting in a nondescript Chevy van with Inspector Gregory Ovanessian and several other lawmen, part of a task force hurriedly assembled under the name Operation Foxglove. The police had finally moved, after Faron and Jerry Lama had warned the San Francisco attorney's office that continued inaction could cost the city a bundle in lawsuits if more old men turned up dead. For hours the group huddled in the van, watching Nelson's front door. When no food or visitors arrived, Billy walked up and knocked. "We're very concerned about you," he told the old man. "May we come in?"

The small home was neat and clean. As he reported later, Billy found the 92-year-old barely competent. Ovanessian asked about the woman who'd been visiting, and Nelson said, "Oh, yes. She lives with her brother. But we're gonna get married. I love her, and she loves me."

The visitors bagged samples of macaroni salad from containers marked French Village Deli. Nelson offered to show them his fiancee's room.

"I've fixed it all up."

Bank records lay in plain sight on the dining-room table, indicating a joint account in the names of Nelson and Angela Bufford and another account in Bufford's name alone. A third account showed a zero balance. Billy did a quick scan and estimated that the old man's twilight affair had cost him at least $60,000 so far.

Ovanessian picked up a loose check for $200 made out to Angela Bufford, and asked, "What's this for?"

"She needs some money," Nelson replied, "and I try to help her out."

The food samples were delivered to the medical examiner's office, but no public report was made on their contents. Nelson's blood tested positive for digitalis despite the fact that his personal physician said that he'd never prescribed the heart medicine.

After the city attorney informed the police that California law required them to warn the old man about his peril, Ovanessian and his colleagues drove to Nelson's house and parked behind Angela's silver BMW. They went inside and, in front of Bufford, told Nelson, "This woman is really Theresa Tene. She's a Gypsy, and she's been poisoning you." Angela told them to call her lawyer, and after two hours of questioning they were forced to let her go.

Glen Billy contacted the old man's relatives, and Nelson was whisked to a nursing home in another county, still rhapsodizing about his beautiful fiancee. A few days later Angela showed up at the nursing home, but she was turned away.

"These old men are gonna die. What's the holdup? And the cops are telling me, 'People have civil rights,'" said Faron.

Faron and Jerry Lama were relieved that Richard Nelson was out of harm's way, but they were still apprehensive about Harry Glover Hughes, whose phone number had now been changed by his friend George Lama. A geriatric-mental-health counselor called on the old man and reported that he had very poor memory and was confused.

In an affidavit recommending appointment of a public guardian, counselor Doris So stated: "Client is a prey to a couple, Angela Bufford and her boyfriend George. These people have been trying to take advantage of him financially." She placed Hughes in the care of professional nurses.

On March 30, 1994, six months after Faron had first videotaped George Lama delivering deli snacks to the old man, Hughes was found dead on the floor of his house. The cause listed on his death certificate was hypertensive intracerebral hemorrhage. A pacemaker was found to be in working order and his blood uncontaminated. It was impossible to determine how much of his personal fortune had been skimmed, but George took immediate possession of the co-owned Mercedes. Because a nephew of Hughes's had been alerted, the remainder of the estate, some $1,085,000, was distributed to relatives, friends, and charities.

It was a month after this latest death when police and the district attorney's office finally decided to exhume Angela's dead husband, Nicholas Bufford; her would-be client Storvick; Mary Tene's husband, Philip Steiner; and Mary's former charge, Konstantin Liotweizen.

Officials were as closemouthed about the test results as they had been about their lack of progress on the case, but private investigator John Nazarian, a police confidant and a Gypsy expert, claimed to have seen the toxicology reports and confirmed that all four bodies had tested positive for digitalis.

"The inspectors told me that the findings didn't help their case, because there wasn't enough digitalis to kill," Nazarian commented. "I said, 'What the hell's the difference? Why should digitalis show up at all if it's never been prescribed?' "

Fay Faron, Jerry Lama, and friends of the victims' reached the reluctant conclusion that the police were stalling, a feeling that was reinforced when lead detective Greg Ovanessian was reassigned to a money-skimming case in Candlestick Park. Now the complex investigation was in the hands of Ovanessian's younger partner, Daniel Yawczak, who was busy in federal court defending himself against a civil complaint that he'd used unnecessary force in the fatal shooting of a teenager. (In March, the Supreme Court let stand an earlier court decision awarding damages to the victim's family.)

When Lama asked if the San Francisco chief of police wasn't upset by the fact that helpless seniors were being poisoned on his watch, he was reportedly told, "The chief's got enough problems to worry about. He's being charged with sexual harassment. You think he cares? He's gonna be retiring." (A federal jury later determined the police chief was not guilty of harassment.)

Jerry Lama cared, and so did Fay Faron. Month after month they harangued social agencies, the police, the district attorney, the city attorney, and the mayor's office. Reluctantly, Lama and Faron decided that it was finally time to go public.

Faron contacted a friend, Dan Reed, a rumpled, meticulous reporter for The Oakland Tribune, with high-end hearing loss from his years as a rock drummer. In his spare time Reed, 39, checked out leads from Faron's files and developed some of his own; police and the D.A.'s office ignored his calls.

District Attorney Terence Hallinan yelled, "Damn it, these Gypsies are killing people!"

On June 28, 1994, Reed broke the story on the top of page one of the Tribune under the headline A BIZARRE TALE OF MARRIAGE, DEATH, and pounded it hard for weeks. The San Francisco Examiner scrambled to catch up, with an article headlined SCHEME TO KILL SENIORS FOR PROFIT SUSPECTED, while its sister paper, the venerable Chronicle, proclaimed, s.F. MEN MAY HAVE BEEN DEFRAUDED, THEN POISONED.

On the tidal wave of publicity, reports of other, similar scams bubbled to the surface. A retired 85-year-old New York City publisher died with digitalis in his bloodstream after marrying the companion of Angela's distant cousin Tom Tene. Reporters for the ABC-TV newsmagazine 20/20 turned up a 90year-old San Franciscan who'd been pauperized by a female from the Gypsy Yonko family. An aging San Diego man reported paying local Gypsies $675,000 to revive his libido through prayer and incantations.

Stung by the media blitz, the San Francisco authorities began another burst of secret activity. The Lama-Bufford house was searched; George and Angela were interrogated and released again, and their four vehicles were impounded temporarily for a French Connection-style examination of their interiors.

In the summer of 1995, charges were finally filed, but not against George Lama and the outlaw Gypsies. Internal-affairs authorities ordered Inspectors Greg Ovanessian and Daniel Yawczak to answer to departmental complaints of malfeasance with regard to the Gypsy case. The district attorney, who had kept demanding more evidence, and the police supervisors, who had seemed to discount Operation Foxglove from the beginning, didn't get around to questioning their own behavior in the case (nor was any member of the San Francisco Police Department or district attorney's office permitted to discuss it with Vanity Fair).

Faron spent the first half of 1997 seething in silence as a colorful new district attorney, Terence Hallinan, showed no more interest in the elder scams than his predecessor had. "If the police can't protect our elderly," she complained, "who can they protect? Who the hell is safe?"

Faron channeled her outrage into creating a nonprofit group called ElderAngels, aimed at preventing abuses against senior citizens. She was surprised when word began to circulate that Hallinan was convening a grand jury to look into the Gypsy cases.

Faron phoned a source inside the mayor's office, who explained, "Hallinan was looking through old cases and came across this one. He asked everyone if they thought it should be revived. The top police guys said, No way—you reopen this case, we're all down the tubes. Some of the D.A.'s own people agreed, but for different reasons. They figured the city had spent too much time and money on the case, and it was a sure loser anyway. They counted noses, and it came out something like 10-to-l to give the Gypsies a pass. Case closed."

But for some reason, Hallinan took home the files. Then he looked through a whole box of reports, and came into the office yelling, "Goddamn it, these Gypsies are killing people!" He put his senior man on the case, told him to take as long as he wanted.

The grand jury convened in July 1997. Over a four-month period, 112 witnesses testified. On November 6, 1997, almost exactly five years from the day Nicole Lama had first made an anonymous call to the Fraud Unit, the grand jury returned a sealed, 96-count indictment, charging Mary Tene Steiner with two counts of conspiracy to commit murder, plus lesser charges; George Lama and Angela Bufford with six counts each of conspiracy to commit murder, plus lesser charges; Lama's nephew Roland Dabai with two counts of conspiracy to commit murder; Danny Tene with nine counts of stealing from a dependent adult, and one count of grand theft.

The defendants entered innocent pleas. Robert Sheridan, Angela Bufford's attorney, said the murder-by-poison story was "missing only two things: poison and murder." The judge set a million-dollar bond for Danny Tene and held the others without bail. Trials are scheduled for later this year. Like many of the courtroom observers, Faron couldn't stop looking at Angela Bufford. As she took her place next to her gadjo boyfriend, she brushed back the dark-brown hair that fell to the shoulders of the orange unisex jumpsuit supplied by the City and County of San Francisco and smiled graciously at the judge and her fellow defendants.

Faron thought, Isn't she the cool one? Just like the morning when I brought her the questionnaire . . . And she looks so good in orange.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now