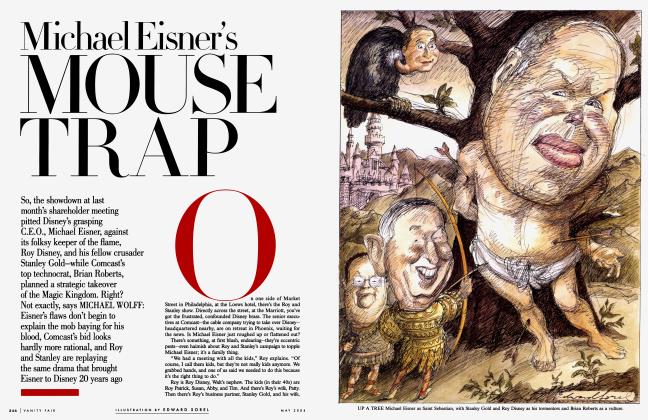

Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

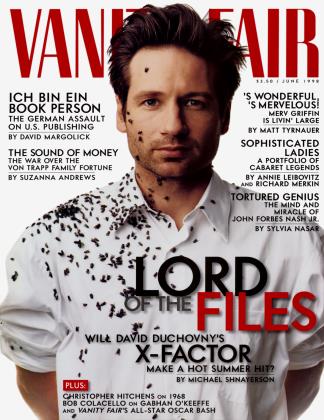

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowHas Gabhan Gone GAGA?

Gabhan O'Keeffe, the most controversial and talked-almut interior designer of the decade, appears to be infectious: Nan Kempner and Isabel Goldsmith caught him from Sao Schlumberger, who caught him from Princess Gloria von Thurn und Taxis, and so on. Viewing O'Keeffe's latest projects and the decorator's own fantastically fiii^fosiecte London carriage house, BOB COLACELLO learns how a 41-year-old Irish dandy from South Africa inspires clients to go for broke with I zanily original, over-the-top visions

BOB COLACELLO

FOR DETAILS, SEE CREDITS PAGE

"People look for life on Mars or the moon, but, my God, there's another life all around us," says O'Keeffe.

One of the nice things about this house is that the central courtyard is just big enough to hold a symphonic orchestra," says Gabhan O'Keeffe, the 41-year-old, pop-eyed, wild-haired Irish dandy from Lesotho who is possibly the most important, probably the most original, and certainly one of the most talked-about decorators of the 1990s. O'Keeffe took the chichi world of international interior design by storm five years ago with his beyond-Baroque apartment for Paris grande dame Sao Schlumberger and has since attracted such high-profile clients as Venezuelan media tycoon Gustavo Cisneros and his arts-patroness wife, Patricia Phelps de Cisneros; New York social icon Nan Kempner; Isabel Goldsmith, the eldest daughter of the late Anglo-French billionaire Sir James Goldsmith; and film director David Rocksavage, the seventh Marquess of Cholmondeley. O'Keeffe is giving me a site tour of his latest project in progress, a four-story, 12,000-square-foot town house on Montpelier Square in the Knightsbridge section of London. This is the first house he has designed and built from the ground up. It is also London's first prominent "teardown," to use a term coined in Los Angeles in the 1980s, when Candy and Aaron Spelling started the trend, now common in that city's wealthy neighborhoods, of buying a property for its location, tearing down the existing mansion on it, and putting up a bigger house in its place. In this case, the existing building was the four-story embassy of Oman. "It was a very tough nut to crack, in terms of pulling it down," O'Keeffe notes, "because it was built as a bombproof structure." As he often does, he ends his sentence with a long, loud, almost maniacal burst of laughter.

"Let's sort of skedaddle around here," he continues. "This is the entrance. The doorway itself is about 16 feet high—the whole door casing, with the oeil-de-boeuf and everything. And then the real surprise is that when you come into this room, which is the dining hall, you have a view of this fantastic inner courtyard, which is a very, very unusual feature for a London house. The floor here is an ivory-buttermilk stone, inset with red porphyry and a deep-, deep-, deepchocolate stone, in these little patterns. There's a similar floor in the courtyard, so you'll read this room and the courtyard together, and you'll have this incredible sense of space. When you're in here, you're in a completely different world. It's totally private, private, private—very much the way an Italian Renaissance family would have lived."

While the antique-yellow brick exterior of the house will "beautifully match" those of its Georgian neighbors on Montpelier Square, O'Keeffe says, "the interior's another story," with its main rooms looking out onto the Palladio-inspired courtyard through "diaphanous" walls of pale-ocher beveled glass. "Can you imagine the glass twinkling about when all the lights are on at night? It's going to be magic." He leads me up a ladder to a second-floor drawing room, one of eight reception rooms in the house, which will also have eight bedrooms, a chess room, a room O'Keeffe calls the "decadent space," and a four-car underground garage. "Whooh! This room is 48 feet long," he announces. "They are going to play and play and play here. I always think it's so nice to have a house where you can actually promenade—you know, where you don't feel desperate to get out and go sit in a cafe."

O'Keeffe is building the house for Sandra Ballantine, a young fashion stylist and art collector from New Jersey, and her companion, an English financier. "She was initially looking at terrace houses to buy," he says. "And I said, 'Listen, baby, forget it. You're not going to get what I think you want in a terrace house.' So I started looking and found this embassy building. My client came to see it, thinking we were going to renovate it. I sat her down and said, 'Well, actually, we're going to pull it down.' It was just a matter of getting her over that very small, little moment in time of fear." He pauses and adds, "The fear that what you've just bought is going to disappear." Then he lets out a gale of rollicking laughter.

• Keeffe seems to have a knack for getting his clients to go all the way, or at least a lot further than they had planned. "My original brief was for more cupboards and a garden pavilion," says Isabel Goldsmith. "And I ended up having the whole house redone. So he does get one enthused." Goldsmith's South Kensington row house had been handsomely decorated by the late Geoffrey Bennison shortly before she dined at Schlumberger's apartment and was so impressed by the bedroom closets, which have velvet curtains in lieu of doors, and an armoire crowned with a cupola "large enough to hold a man," as O'Keeffe puts it, that she asked him to find equally amusing ways to increase her closet space, and to replace a trellised structure in her garden with an enclosed folie for rainy-day reading and tete-a-tete entertaining.

"Gabhn's artistic-ness is catching When you meet him, you immediately want him to do something for you."

"I thought what he had done for Sao was incredibly original," Goldsmith says. "I loved the fact that so many things were made specifically for her, that he had commissioned those mad Murano-glass doorknobs in Venice, for example. I didn't want a decorator who just goes to Braquenie in Paris or Clarence House in New York and buys the same expensive fabrics everyone else has. Gabhan weaves all his own fabrics." O'Keeffe persuaded her to enlarge her dining room, have the walls muraled, the ceiling carved, and the beams and columns gilded. One Arts and Crafts-style room led to another, and Goldsmith, after living with friends for nearly two years, finally reoccupied her house this spring.

"His artistic-ness is catching," says Nan Kempner, who had O'Keeffe "update" the library in her Park Avenue duplex this year. "When you meet him, you immediately want him to do something for you." Kempner "wasn't really" planning on having her classic, brown-and-white-lacquered library, done by the late Michael Taylor in the 1970s, redecorated. "But Gabhan came for lunch, and [the late decorator] Chessy Rayner came in wearing a saffron-yellow shawl and a red dress. And I said, 'If I were to redo my room, I'd do it just like that.' The next thing I knew, I had swatches from Gabhan. As I say, he's contagious." Now she's got a tomato-red-and-yellow wool sofa, red-yellow-andcream curtains with straw and beige trim, and ocher walls stenciled with burnt-sienna artichoke leaves. "Two very nice guys from England painted in there all day and all night for 10 days," she says. "The walls just sing." Amazingly, the Kempners' Magrittes stand out more than they did against a solid background. Even more amazingly, the notoriously conservative Thomas Kempner, a Wall Street investment banker, "adores this library. We're both thrilled to death with it. It could be busy, but it isn't."

T ike Isabel Goldsmith, Nan Kempner "caught" O'Keeffe ⅝ Jfrom Sao Schlumberger, who is still happily ensconced in the Seventh Arrondissement apartment that so divided Paris society when she moved in that Loulou de la Falaise almost came to blows with Beatrice de Rothschild while debating its merits at a dinner party. After photographs of it were published in this magazine in October 1993, rival decorators denounced it in print, even though most of them hadn't actually seen it. Renzo Mongiardino, the late Italian master of over-the-top opulence, declared it "terrible" in W and went on to accuse O'Keeffe of copying him. Robert Couturier, the young French architect and decorator whose principal client was Sir James Goldsmith, told the New York Post: "It is about the most atrocious thing I've come across. This is a design that has no balance, no restraint and no respect for architecture. It looks like the house of Bozo the Clown."

"I find it as pleasant and as exciting as it was in the beginning," Schlumberger says. "Even though I've had some personal problems, I cannot be CONTINUED FROM PAGE 194 depressed for long in this background—the colors are so joyful." says. "There again, she had the guts to do it. She confronted fear in its face. Boom! Pah! Away you go. And off we went."

CONTINUED ON PAGE 216

CONTINUED FROM PAGE 194

As he clambers about the Montpelier Square construction site—wearing a darkblue Bavarian-style suede jacket, a khaki linen vest, a Turnbull & Asser checked shirt with amethyst cuff links, a brightorange silk tie, gray corduroy trousers, work boots, and a white hard hat— O'Keeffe recalls that the Schlumberger project was also a teardown of sorts. Schlumberger had already spent more than a year working with a minimalist architect when she visited the late Prince Johannes von Thum und Taxis at his 500room palace in Regensburg, Germany, and was so swept away by the wing O'Keeffe had reconstructed and decorated for the prince's uproarious young wife, Princess Gloria, that she decided to go for Baroque, too. "Sao's project was almost complete when we tore it out," O'Keeffe

6T et me just pop a little cardamom I iinto your rose water," says Gabhan O'Keeffe before handing me a crystal goblet filled with pink liquid specked with floating black seeds. We are having drinks before dinner in the downstairs sitting room of the three-bedroom carriage house in Knightsbridge he shares with his design partner of 10 years, George Warrington, a scion of one of England's most aristocratic Catholic families. The fireplace is pewter-foiled and some of the walls are copper-leafed; the other walls are hung with vermilion-and-azure silk damask designed by O'Keeffe. An 18th-century pastel portrait of Mozart hangs over a gracefully curved sofa, also designed by O'Keeffe, as was the handwoven crimsonand-gold fabric in which it's upholstered. There are 17th-century side chairs from Old Richmond Palace, 18th-century Russian gilt-and-ivory stools, and a pair of 19th-century carved temple guards from India. The decorator puts what looks like a piece of bark into a silver filigreed incense burner, saying, "It's the most amazing thing I've been sent from Cambodia. I'm a totally addictive person, but my thing is incense." Then he slips a CD into a hidden player. "I want you to hear the sexiest thing," he says, "the only cello sonata Chopin wrote."

Sitting in O'Keeffe's out-of-this-world, fin de siecle lair, I suddenly realize that he is a 20th-century reincarnation of Des Esseintes, the hyper-aesthetic hero of Joris Karl Huysmans's novel Against the Grain, published late in the last century. "The five senses—the five gifts that you're given—are the most important thing," O'Keeffe says. "And that's what makes life work for one, really. To me, the great thing about life is that it's got endless possibilities. I love to go where there's an incredibly vivid sense of life. I recently went deep-sea diving among coral reefs in Mauritius. I love diving because you see shells and shells and shells, thousands of fish. People are always looking for life up on Mars or the moon, but, my God, it's already here. There's another life all around us, actually, on this earth.

"I've always had a great passion for what I do now, basically," O'Keeffe says. "I'm still continually referring to imagery that really struck me as a child. Textures. Colors. Shapes. Structures. Light. Landscape—where I was brought up, in fact, it was completely wild. And decorations. And the sounds of different languages— Zulu, Swahili, Swazi. The one house that I lived in was set against a very, very dramatic backdrop. I remember an enormous face of rock going up hundreds of meters. I have this image of once being struck by lightning. It was the most extraordinary event."

A ccording to the brief biographical note distributed by Eleanor Lambert, O'Keeffe's New York publicist, he "was born in the Drakensburg Mountains in Africa, of Irish parentage." It's difficult to get him to be much more specific than that, although he has told me that he grew up on his grandfather's isolated, 150,000-acre estate in Lesotho, a small kingdom completely surrounded by South Africa, where he was educated by a tutor and studied classical music several hours a day. "Musical training," he says, "is excellent training for what I do now. Because you're dealing with something highly emotionally charged, but actually, at the end of the day, it's all facts and figures too. A quarter-note's a quarter-note, and a hemidemisemiquaver's a hemidemisemiquaver. It's never going to be anything else."

As one of his earliest clients and best friends, Lucy Ferry, the wife of British rock star Bryan Ferry, says, "Gabhan's a mysterious creature. There's no doubt about it." Apparently O'Keeffe arrived in London as a teenager in the 70s. He was enrolled at City University from September 1977 to June 1978. In 1983-84, he took Christie's one-year course in fine and decorative arts. For a time he worked as an assistant to the late O. F. "Jack" Wilson, a well-respected antiques dealer on Fulham Road in Chelsea.

"Mr. Wilson liked Gabhan's enthusiasm," recalls Peter Jackson, who now runs the O. F. Wilson shop. "But he used to drive Mr. Wilson mad half the time. 'He's not very practical,' Mr. Wilson used to say. 'He's very Irish.' He did work hard. He was not one to sit around. And he was very, very social. He was always very keen to get ahead. He met Lucy Ferry here. She came in to buy a chandelier, and he kept on with her. We didn't know he did. He didn't tell us he was seeing her, but he was. She was inviting him to parties, and she became his client. More credit to him."

During this period, several friends recall, O'Keeffe was living in the basement apartment of a house on Norland Square owned by an older South African gentleman. "He started life very simply," says Hannerle Dehn, an expert furniture restorer who worked with Wilson and who helped O'Keeffe fix up his apartment, "with bits he had and bits I gave him. Everyone heard different stories about Gabhan and his upbringing. He talked to me more about his ambitions. He was a highly intelligent person and greatly gifted. He was a larger-than-life figure even then."

TT'ashion editor Isabella "Izzy" Blow met A. O'Keeffe when he was living in the basement apartment. "It was very colorful, with lots of candles everywhere—all the Gabhan church trademarks. He dressed the same way he does now—lots of stripy things. Irish on top, Oriental underneath. He looked like a Picasso Harlequin, with those big blue eyes popping out. And he had the same Irish lilt."

"Izzy rang me," recalls Lucy Ferry, "and said, 'You've got to meet Gabhan.' Then he found this amazing chandelier for our London house. He had done a job for William Hurt, the actor, in New York, and we had just bought a loft on East 12th Street. So we asked him to help us with that. It was basically a painting job. Because the loft had been completely designed by Max Gordon, who was very minimalist and clean. And Gabhan is very flamboyant and very much into color. Looking back on it, it was quite a bizarre mixture. Gabhan painted the dining room this very deep sea green. And he actually lacquered the vestibule himself—a Chinesered lacquer, which was so beautiful. And then he got the job with Gloria von Thum und Taxis soon after that.

"Gabhan's got such an incredible vision. With me, he didn't get into the whole orchestra of making the furniture and curtains and carpets and everything. He thinks everything ought to be unique to each client. He's very sensitive to women. He's wonderful company, and he's got this musical side as well, which I think is very connected to what he does visually. It's as if each part of what he does is a different instrument. When we were living in Los Angeles, he used to come over and play the piano. It was such a luxury to have someone just come in and play this wonderful classical music. And with no music books or anything. It was just in his head."

TT'or the last five years, the New York art world has been awaiting the unveiling of Gabhan O'Keeffe's largest commission in this country: a loft in SoHo for European contemporary-art collectors who wish to remain anonymous, featuring some 40 pieces of furniture in botanical shapes designed by O'Keeffe and Warrington. In the recently completed main room, beneath enormous works by Gilbert and George, Sigmar Polke, and Jeff Koons, there are a nine-foot green sofa in the shape of a leaf—reminiscent of Dali's Mae West lips sofa—a giant red tiger-lily chair, a purple-and-yellow sunflower ottoman, and several daisy stools. In the dining area are a pair of water-lily tables with Faberge-like tops, of silvered copper enameled in glistening blues and greens. The kitchen looks like a Neo-Geo painting by Peter Halley. The loft, with its chalk-white plaster walls and curtainless windows, is shockingly avant-garde for O'Keeffe. "The project was put together like a piece of jewelry," O'Keeffe explains. "I love modern materials. I'm a great advocate of looking forward and going ahead all the time."

O'Keeffe has a knack for getting his clients to go all the way, or at least a lot further than they planned.

In England, O'Keeffe's most important new client is a major Labour Party politician who cannot be named. He and his wife hired O'Keeffe to decorate the master-bedroom suite of their country house, which was built by the great English architect Sir Edwin Lutyens in the 1920s. "The first thing this client said to me was 'Everything must be Britishmade,'" O'Keeffe says. "'Nothing must come from anywhere else.' Then, of course, I really showed him what Britain could do. He was quite surprised, I must say."

The politician's wife gushes, "Gabhan has only to enter a room, look at the person, and conjure up everything. He found what was in my soul, what I didn't even know how to express, and created exactly what I wanted. I want to go on and on with him. He'll be doing my drawing room and my music room. I was in his studio yesterday, and from what he showed me, I just can't wait. The colors for my music room—turquoise over a burnished gold and several shades of pink—are just like a Zeffirelli set, which for me is the highest compliment I can pay. He really finds top craftsmen. Sometimes I can hardly believe they're from England—we used to import craftsmen from Italy, because we thought we had to. But they're all here—the upholsterers and weavers and gilders and painters, the woodworkers—if you know where to find them, as Gabhan does."

For all his success at home and abroad, O'Keeffe still has some highly vocal detractors. "I think he's a horror," says Nicky Haslam, the very social London decorator. "I think the taste is absolutely awful. People say he does the most marvelous handmade fabrics. Who wants handmade fabrics? We don't live in Venice in the Fortuny era. His approach is everything I don't like—miles of curtains with swags and tassels. It's over, over, over. And thank God it is."

But O'Keeffe also has plenty of potential new clients, including a well-known South African guitarist with nine wives and 16 children. "He's a very, very rich man, and has moved back to Zululand because he wants to raise his children as traditional Zulus," says O'Keeffe. "I'm game for that, actually. Anywhere in the bush, anywhere where there's a wonderful sunrise, anywhere in the world, basically, is exciting to me." □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now