Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

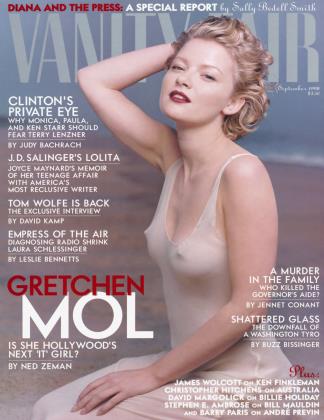

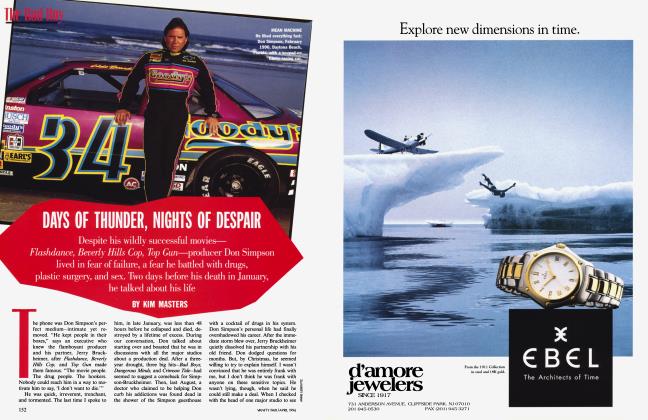

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowA KNIGHT AT THE OPERA

Sir André Previn has composed ballets for Gene Kelly, created musical drama with Tom Stoppard, played jazz with Ella Fitzgerald, and conducted every major orchestra in the world. This month in San Francisco, the versatile artist, whose private life has been nearly as convoluted as his career, premieres his first opera, A Streetcar Named Desire

BARRY PARIS

Music

André Previn's music has never depended on the kindness of strangers, friends, or critics. But every streetcar needs a conductor, and the one named Desire needed a composer first. Turning Tennessee Williams's masterpiece into a viable opera requires as much audacity as talent, which is why reviewers will probably be gunning for it when it premieres on September 19 at the San Francisco Opera (S.F.O.).

"If that worried me, I couldn't write anything," says the imperturbable Previn— Sir Andre since 1996—the most multiaccomplished crossover musician of this century. Previn is the last great universalist in a world of musical specialists: winner of four Oscars for film scores, virtuoso classical and jazz pianist, composer of symphonic and chamber works and song cycles, prolific recording artist, and, at one time or another, conductor of all the world's major orchestras.

In one spectacular period during his tenure as music director of the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra (P. S.O.), he conducted a dozen subscription programs, Bach to Penderecki; premiered the music drama Every Good Boy Deserves Favour, which he wrote with Tom Stoppard; played a jazz benefit with Ella Fitzgerald; studied Frank Zappa's "Bogus Pomp" for a pops concert; and subbed at the last minute for an ailing soloist by playing Mozart's Piano Concerto No. 24 himself ("one of four I keep at the ready," he says) while conducting from the keyboard.

Astonishing versatility and international superstardom are as likely to be punished as rewarded in the classical-music business. Isaac Stern called Previn "one of the most underrated great conductors in the world." But in American culture, Previn has said, "I would have been more readily forgiven for being the Boston Strangler than for having written a film score."

Pittsburgh is illustrative. He was criticized there for his "aloofness" and his failure to socialize sufficiently with the local C.E.O.'s and their wives, whose parties he relished like a root canal. ("I don't want someone to give the orchestra an extra fifty thousand dollars just because I've played tennis with him," he once said.) While he was with the P.S.O., from 1976 to 1984, however, Thursday concerts had to be added to its traditional Friday, Saturday, and Sunday performances in order to accommodate the increased audiences he drew.

Born in 1929 in Berlin of RussianJewish parents, Previn was a piano prodigy, accepted at age six by Berlin's Hochschule conservatory but forced to flee with his family in 1938 to France and then to Los Angeles, where his father's cousin Charles was a music director at Universal Studios. Andre became a U.S. citizen in 1943. When he was a teenager, his musical odd jobs included playing the piano in a silent-movie house, where he was fired after a screening of D. W. Griffith's Intolerance for playing "Twelfth Street Rag" during the crucifixion scene.

Previn started working as an orchestrator for MGM before graduating from high school. ("Studio blurbs presented me as a kind of Mozart turned Jackie Cooper.")

"I always thought Streetcar was an opera that was just missing the music," says Previn.

Soon he was writing harp glissandos for Esther Williams and ballets for Gene Kelly—some 50 film scores in all. "You cannot imagine what leaps out of the shadows at me from the television at three in the morning," he says. "I don't get paid for most of them, but I should—if only for the embarrassment."

Like his score for Valley of the Dolls, perhaps?

"Oh, no, that was big-time. I'm talking about really loathsome pictures in my early 20s, when I was under contract at MGM and they used to grind out those double bills like TV shows."

Like the Lassie films?

"I can take the blame for only two of them [The Sun Comes Up in 1948 and Challenge to Lassie in 1949], Sun Comes Up was the first movie I ever did—and Jeanette MacDonald's last. I liked it because there was no dialogue, just a lot of barking."

Previn would eventually win Academy Awards for best music score for Gigi (1958), Porgy and Bess (1959), Irma La Douce (1963), and My Fair Lady (1964). His other memorable Hollywood scores included Bad Day at Black Rock (1955), Designing Woman (1957), Elmer Gantry (1960), Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse (1961—"I robbed Shostakovich blind," he says), Billy Wilder's One, 7\vo, Three (1961) and Kiss Me, Stupid (1964), Long Day's Journey into Night (1962), and Inside Daisy Clover (1965).

In the early 60s, Previn began conducting major American and European orchestras, becoming principal conductor of the London Symphony Orchestra in 1968 and later its permanent conductor laureate. In the 70s and 80s, when he was music director of the Pittsburgh and Los Angeles orchestras, he composed an increasing number of symphonic and chamber pieces and song cycles, and he continues to conduct about a hundred concerts a year.

The numbers in his private life are equally impressive: four wives, nine children. The two eldest are from his marriage to Betty Bennett, a jazz singer, from whom he split in the late 50s. In 1970 he divorced his second wife, lyricist Dory Langdon Previn, to marry actress Mia Farrow (briefly Mrs. Frank Sinatra) after she had given birth to their twins, Sascha and Matthew. They would have another natural son and adopt three Asian orphans before divorcing in 1979. One year later, Farrow became involved with Woody Allen.

The Farrow-Alien relationship lasted through 13 films, until 1992, when she discovered his affair with Soon-Yi Previn, 20, a Korean orphan she and Andre Previn had adopted during a 1977 trip to Seoul. In the subsequent lurid court battle, Farrow accused Allen of molesting their seven-year-old adopted daughter, Dylan— no charges were ever filed—and successfully fought off his attempt to gain custody of Dylan and sons Satchel and Moses.

It was an excruciating time for Andre Previn, who had remained Soon-Yi's father figure even after he and Farrow split. With Soon-Yi's later marriage to the director came the ultimate galling irony: Previn is now Woody Allen's father-in-law! Constantly pressed to discuss it, Previn will say only "No comment." But last year he expressed his smoldering anger to London's Daily Telegraph: "I'll tell you what I think of Woody Allen. I think he is the worst human being on the planet. I think he is the worst human being I have ever heard of, read of, or been able to imagine."

For Vanity Fair, he adds a clarification: "My peremptory 'No comment' regards Mr. Allen. But I don't want that to be translated to Mia, whom I really like a lot. Our relationship is that we've remained very close friends. We talk to each other about any and all subjects, any and all troubles. I like to think that she's always glad to hear from me, and I'm always glad to talk to her. Mia is a terrific girl, one of the dearest people in my life. I want to make sure that's clear."

Does he want to say anything about Soon-Yi?

"No. That is a closed chapter."

Once considered the epitome of jetsetters, Previn now lives calmly on Martha's Vineyard with his wife, Heather Hales, 50, a British jewelry and glass artisan, and their 14-year-old son, Lukas (who plays "a very decent jazz guitar"). "You can be a very quiet guy—very quiet—and still have four wives," he has said. "I have been happily married now for 15 years, and there is a statute of limitations to a reputation."

Once, during an NPR interview, Previn was asked about the conventional wisdom that singers are less intelligent than instrumentalists. It's an old music-biz cliche, he replied, possibly true in the 18th and 19th centuries, when vocalists lacked education, but "totally false today—except, of course, for tenors." Previn's quotable drollery is complemented by an uncanny ability to speak in perfect paragraphs.

Until I interviewed him in 1993 for a biography of Audrey Hepburn, no one had ever bothered to ask him in any detail about his—and Hollywood's—last great film musical. My Fair Lady opened on Broadway with Julie Andrews and Rex Harrison in 1956 and ran for 2,717 performances. Warner Bros, paid $5.5 million for the screen rights, and at a total cost of $17 million the movie was the most extravagant musical ever. It was Jack Warner's swan song, and he wanted Audrey Hepburn as Eliza Doolittle.

Hepburn worked 12 hours a day in rehearsals, determined to sing her own songs. Music director Previn did all he could to help. Her musky mezzo was not a finely trained instrument, but she had used it to good effect in Funny Face.

"Audrey's voice was perfectly adequate for a living room," Previn says. "If she got up around the piano with friends and sang, everybody would rightfully have said, 'How charming!' But this was the movie to end all movies ... By the time Lerner and Loewe got through telling us how to approach it, it had more traditions than the Ring at Bayreuth. Everybody treated it like it was the Key to the Absolute."

Dubbing was a time-honored but erratic Hollywood practice. (Previn is still incensed that Ava Gardner was not allowed to sing in Show Boat: "When you heard her do 'Bill,' she broke your heart, but they couldn't see it.") In the end, Hepburn's voice was used for a small portion of My Fair Lady. The rest was performed by Hollywood's most "unsung" singer, Marni Nixon, known as Dubber to the Stars.

Rex Harrison, meanwhile, insisted on filming all his numbers live—an unheard-of practice in Hollywood. A special mike was set in his tie, with a transmitter strapped to his leg, so that his singing could be taped over the pre-recorded orchestral accompaniment. "It made it much easier for Rex," says Previn. "But it left me with that insane delivery of his without any accompaniment except the piano, which was fed into his ear. So I had this madman with the up-and-down voice, and I had to put on earphones and chase him with the orchestra. That was hard work. Which he never acknowledged."

Lotfi Mansouri, the innovative general director of the San Francisco Opera, has a $42 million annual budget, exceeded only by that of the Metropolitan Opera in New York. Mansouri pioneered the use of supertitles—a projection of the translation of what is being sung—the most revolutionary boon to American opera audiences (and ticket sales) in generations. He recently directed Alban Berg's Lulu and the little film-within-the-opera it requires. George Lucas had said he would do it for $250,000 per minute of the Film. Mansouri Figured out how to do it with computer graphics for a fraction of that.

"I've wanted to do Streetcar for 15 years," says the Iranian-born impresario. "I felt Blanche could be a Norma or Lucia—one of the greatest female characters in the repertoire. Long ago, the First composer I wanted was Leonard Bernstein. He turned me down. Later, I cornered Stephen Sondheim, and he said, 'Oh, it's such a good play—it doesn't need music.' Well, you can say that about Shakespeare's Othello too."

Mansouri's association with the San Francisco Opera goes back 35 years, encompassing his stints with the Zurich, Geneva, and Toronto opera companies. He took the helm in 1988 with many dreams—most of all, to comipission operas based on Dangerous Liaisons and A Streetcar Named Desire. The first was a sellout success in 1994. In the case of A Streetcar Named Desire, he had to have a composer in place before going to the Tennessee Williams estate for the rights.

"I don't let go," Mansouri says. "I got together with Franco Zeffirelli— who was going to direct and do the libretto—to Find a composer. Franco wanted David Grusin, but he had never composed for voice. Madame St. Just had passed away ..."

He is too polite to add the word "fortuitously," but it is implied: Lady Maria St. Just, the superprotective co-trustee of Williams's estate, could be nightmarish to deal with. She was as cross "as two sticks," Williams once wrote. Under her, the estate's preference for composer was Marvin Hamlisch.

Trusteeship then passed to the University of the South, under the benign administration of New York attorney Michael Remer. Mansouri and his musical administrator, Kip Cranna, thrashed about for the right musical voice, and one day Cranna suggested Andre Previn.

"I had written a lot of vocal music for quite a few of the really good sopranos around now [Kathleen Battle, Sylvia McNair, Barbara Bonney], but never contemplated writing an opera," says Previn.

In 1994 a French company had asked him to write one and sent him the story it had in mind. "I called back and said,

'I can't write it. I don't know how to write for people in togas.' I wouldn't know how a person in a toga really thinks. I know the Mozart and Handel operas, but I'm neither Mozart nor Handel."

"I'd be more readily forgiven for being the Boston Strangler than for writing a film score."

Previn finds a lot of grand opera "slightly ludicrous. Some of the libretti are beyond me. I mean, even if the music is a work of genius, who ever understands II TrovatoreT' But three and a half years ago, when the San Francisco Opera asked him to compose A Streetcar Named Desire, he says, "I didn't have to contemplate much. It was a move of some temerity on my part. I decided I could not live through someone else doing it. I always thought it was an opera that was just missing the music, with all the excesses of lust and madness in the plot."

Mansouri is more than pleased with his choice. "Andre gave Hollywood so many great soundtracks," he says. "I listened to his Elmer Gantry score again— it's extraordinary. I didn't want 12-tone. I wanted a gorgeous piece of music theater, accessible but not tacky, written for an audience, not academia."

Nothing is capable of being well set to music that is not nonsense," Joseph Addison declared in the 18th century, and W. H. Auden backed him up in the 20th: "No good opera plot can be sensible, for people do not sing when they are feeling sensible."

The trustees of the Williams estate placed no musical restrictions on Previn. But they wanted to read and approve every, word of the text, so the real pressure was on the librettist. Previn wanted Toni Morrison, who accepted but later withdrew. The task fell to Philip Littell, author of the Dangerous Liaisons libretto set to music by Conrad Susa for the S.F.O. "Philip got [Choderlos De Laclos's] sprawling novel into a workable format," says Cranna. "But with Liaisons he had no one looking over his shoulder. It was public domain; no one could complain if he set it on the moon. With Streetcar the trustees were involved in the whole process. Philip's mandate was to preserve the spirit of the play."

"Studio blurbs presented me as a kind of Mozart turned Jackie Cooper," says Previn.

The collaboration went smoothly. "When Philip submitted something, it didn't want much changing," Previn recalls. "I'd say, 'Could this be a sentence longer? Can we put in a little aria here for Blanche?' Then I would wait for him to do that. I work very fast and he—frankly—works slowly. But there were no artistic problems."

And what does this Streetcar Named Desire sound like? The S.F.O. is keeping the score under wraps with K.G.B.like secrecy. However, a sneak preview reveals that it sounds like Previn's unique synthesis of styles. As a composer, he is a kind of postmodern Richard Strauss— neoromantic at times, neoclassical at others, leavened by the eclectic influences of a virtuosic lifetime. That musical life is in his discs.

A full list of Previn recordings runs to more than 400—12 dozen in the jazz category alone and many more in the classical category. Nobody delivers better Berlioz than Previn, who has recorded all the overtures twice. His other strong suits include Mozart, Strauss, and the Brits—Elgar, Britten, Vaughan Williams.

Previn's chamber recordings are noted for the self-effacing subtlety and integration of his piano with the strings. His favorite ensemble partners, such as cellist Yo-Yo Ma and violinist Itzhak Perlman, are also his good pals. Previn and the ebullient Perlman do jazz and Scott Joplin as well as the highbrow stuff. They once went into Pittsburgh's Heinz Hall together for a concert whistling the Andy Griffith Show theme—in thirds, at Perlman's challenge. "Itz," said Previn upon finishing, "if you weren't such a bundle of nerves, you could be a big star."

Previn's classical compositions include The Invisible Drummer (five piano preludes), a Triolet for Brass, guitar and piano concertos, and a brilliant Trio for Oboe, Bassoon, and Piano, whose jaunty chromaticism rivals that of Darius Milhaud. You'd expect two of his more recent creations for soprano—Honey and Rue for Battle and Sallie Chisum Remembers Billy the Kid for Bonney—to provide a hint of what the DuBois sisters may be singing in San Francisco. But they do not.

Previn's opera—like the play, unlike the movie—centers on Blanche.

"I looked at the [1951 Elia Kazan] film before I wrote note one and not since," he says, "because it's dangerous. The emphasis got switched when everybody's consciousness became suffused with [Marlon] Brando's performance. The play is really about her, and she has an absolutely enormous part in the opera." In transposing Blanche and Stella from speech to music, he made the unusual decision to write both parts for soprano.

"Lotfi said, 'Are you sure you don't want a mezzo [as Stella]?' I said, 'No, I grew up on the Strauss operas, and I love the sound of two sopranos. I want them to be alike in CONTINUED FROM PAGE 228

CONTINUED ON PAGE 233

Voice production and totally different in what they're singing."'

Only half a dozen principals and a few minor characters will ride in this Streetcar. Originally there was to be an onstage jazz combo for atmosphere, but Previn nixed it. "Everyone's assumption is 'Oh, New Orleans—as the curtain comes up, we'll hear a Preservation Hall band, and guess where we are!' No, I don't think so. That's too easy."

The opera's nine scenes are fashioned into two 90-minute acts, divided at the point when Blanche and Mitch exchange sad confessions that they both "need somebody," each thinking perhaps that "somebody" might be the other. "Their stories are full of despair and failure, but Act I ends on that note of uncalled-for optimism," says Previn. "In the next act, of course, everything comes unraveled. Stanley's rape of Blanche is an orchestral interlude while the stage is dark; you presuppose what's going on but don't see it clearly. It's not Schoenberg—Moses urui Aron, where you see all kinds of fucking going on. I couldn't quite see that here."

Opera buffs in and out of San Francisco have been speculating about how their favorite lines will be rendered. "The most famous, of course, is 'kindness of strangers,' which was wonderful to set," says Previn. "I loved doing that. The other is that almost risible screaming of 'Stel-l-a-a/' The orchestra goes quite crazy, but Stanley is just going to yell it. I discussed that with Colin, who agreed with me."

Colin Graham was the first director for nearly all of the late Benjamin Britten's operas. A Streetcar Named Desire is his 53 rd world premiere, and he was involved in its creative process from the start, as he was with Dangerous Liaisons. Previn found it helpful to bounce ideas for the opera off the seasoned veteran: "I said, 'No matter who you get to do it, if he sings "Stel-l-a-a/" we're going to get the most unwanted laughter.' Otherwise it is composed through without dialogue, completely sung except at the end, when the doctor and nurse come for her and say, 'The jacket won't be necessary.' That should be spoken, because their reality is completely removed from Blanche and her dream."

When Renee Fleming said she wanted to sing the role, it was really a stroke of luck," says Previn, "because she's as good as you can get."

Lotfi Mansouri calls Fleming "my dream Blanche" for her "stunning vulnerability" as well as her voice. "Blanche must make me cry, but at the same time she must have a strength: 'Stella, you left—I stayed and dealt with death after death!' Mme. de Tourvel in Liaisons was created for Renee, and it was Renee for Streetcar from the beginning."

For Stella, Previn wanted a lighter soprano with youthful freshness. He found her in lyric coloratura Elizabeth Futral, "who will look very much like Renee's sister" in their duets.

Rodney Gilfry is the hunky opera equivalent of Brando. "We always knew we wanted Stanley to be a baritone," Mansouri says. "I don't know one tenor who looks good in a torn T-shirt."

"No matter who you get to do it, if he sings 'Stel-l-a-aV we're going to get laughter."

As Previn completed major chunks of the opera, he played them for Fleming, who was intimately involved in the process. She had some specific ideas about the musical moments and set pieces she wanted in the role, and shared them with the composer. "She said, 'Do me a favor—write me a couple things I can do for orchestral concerts. Puccini did it, and he was no fool. Give me a couple of big arias I can do away from the opera.'"

Previn did so, and won the undying gratitude of his diva: "That Andre could write for me—the collaboration, when I could say, 'Be careful orchestrating this phrase because it's the weakest part of my voice' or 'Could you put a high note in there to give that phrase a little more glamour?'—was so unusual and wonderful. He was so open to making sure it was the best music for my instrument."

Mansouri had a request, too: "I'm a producer who doesn't have many demands, but when Blanche says, 'I want magic,' I wanted an aria. So he wrote a beautiful aria, very singable, which Renee loves and is recording right now." Cranna describes the aria as "high and floaty. Renee specializes in floating those beautiful high notes, and Andre thinks of Blanche that way—as a fragile, faded, tragic southern belle."

It's the aria and the moment everyone in the production seems to talk about and love most. But, as of this writing, its composer was in the dark about how it sounds. "I have literally never heard it!" says Previn. "We'll be recording the whole opera later for Deutsche Grammophon, but Renee had an immediate contract with Decca to make an album of arias [with James Levine and the Metropolitan Opera Orchestra] and wanted to include this, so I sent it to Jimmy to record in New York while I'm in London [with the London Symphony Orchestra]."

He must have great trust in Levine, I remark.

"Yes," Previn replies, "plus greed. I would be insane if I kept Renee Fleming from recording any aria of mine. There are times when my 'conservative' love of the human voice gets the better of me, and this was one of them. It's surrounded by some very harsh things. The harmonic language is neither conventional nor avant-garde. You can tell it was written in the present, but I'm never going to make [dissonant composer] Elliott Carter nervous. Truly atonal singing goes a bit against my nature. I think singers basically want something to hang on to in terms of a melody."

Previn flirts with more melodies than he actually engages. Unlike many modern works, says Michael Yeargan, the opera's set designer, "Andre's music does not sound like a cat in a Cuisinart. It comes out of the natural spoken words."

Asked about the presumably greater difficulty of singing a new operatic role versus an old one, Renee Fleming says, "In some ways it's easier, because there's no 'standard.' You don't have to live up to somebody else's performance—everyone else has to live up to you!"

After Previn finished his score, "the S.F.O. did something wonderful," he recalls. "They have a school for young singers, and they had those kids learn the songbook. Then we went out for a week and heard it with them. Colin would say, 'I need three minutes here for a scene change' or 'Can we have a little longer music getting her on?' It gave me a chance to do that kind of revision before the first rehearsals.

"So I heard the music about seven hours a day for a week, which was a real trial. When people liked or disliked certain things, I paid attention. If something was too high or too low, I changed it. I had a good time. But if you hear seven hours of your own music every day, by the end of the week—unless you're a real admirer of yourself—you no longer know whether it's any good or not.

"Tom Stoppard, a great friend of mine, has been through this many times. He called not long ago and said, 'Are you finished?' 'Yeah.' 'How is it?' I said, 'It's impossible for me to judge. Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays I think it's pretty wonderful. Tuesdays, Thursdays, and Saturdays I'm convinced it's a piece of crap.' He said, 'You might be wrong on both counts, it might just be always mediocre.' I said, 'I don't need this, Tom!'"

Previn likes Yeargan's provocative set "because it breaks apart, as Blanche does." The most striking feature of the $400,000 design is that everything in it is tilted at an angle of three degrees—half the tilt of a pinball machine.

"Andre's music is introspective," says Yeargan. "The minute you hear those distorted chords, you feel the heat of New Orleans and see Blanche fanning herself on the staircase. It struck me, the whole thing could be Blanche's dream, a subconscious expression of what's going on in her mind. That's why the tilted angles."

Yeargan, who also designed the costumes, says, "New Orleans is the most fantastic place for color—blues, reds, greens blending together into this rich, sexy environment. The play calls for Blanche to wear white at the start, but we decided to have her come in in the Della Robbia-blue traveling suit. All her things are in faded tones mauvy, lilac, chiffon over satiny material, very mosslike and fragile-looking. The others are in much bolder colors—they're alive, happy! Stanley and Mitch come in wearing bowling jackets, with their names on them, of course. And wait'll you see the red T-shirt Stanley changes into— the one that gets torn and connects with those red silk pajamas he puts on later."

After A Streetcar Named Desire, the S.F.O. will undertake another new commissioned piece, based on Sister Helen Prejean's book, Dead Man Walking (with music by Jake Heggie and libretto by Terrence McNally), for 2001. New music scares off most companies, but San Franciscans lap it up. "It's a very intelligent audience," Mansouri says. "I'm a populist. I want to prove opera is for everyone, and I pick subjects with that in mind. Dangerous Liaisons was sold out. Streetcar absolutely will go."

It will "go," Mansouri believes, because "the music is heartfelt and intelligent, not phony-baloney. Andre doesn't write for his ego; he writes for the service of the piece."

"You can be a very quiet guy-very quiet—and still have four wives," says Andre Previn.

Which is also how Previn conducts— Berlioz or Berio—with minimal movement and a precise stick technique to which orchestras respond keenly. Previn is uncompromising in his nonshowmanship. Years ago, he recalled, "Pierre Monteux ... saw me do the 'Tragic' Overture, and afterward he said, 'Listen, before you knock out the ladies in the balcony, make sure the horns come in.'"

Previn will conduct only the first four performances of A Streetcar Named Desire, handing his baton to Patrick Summers for the rest. "I wasn't going to conduct it at all," he says. "I thought I'd be better off pacing up and down in back of the auditorium. But when I mentioned that to Beverly Sills, she said, 'What do you mean? You're crazy. It's practical. When we had a composer sit

in rehearsals and watch someone else conduct, he'd come down the aisle every few minutes saying, "No, wait! That's not what I meant!" It wasted a lot of time. If you're in the pit, you can control it and cut the rehearsal time by hours. Also, on opening night you should keep busy!'"

Will he write another opera?

"Yes. It intimidated me, but also I found that I really like it. I like theatrical things, and it's the perfect combination."

Is A Streetcar Named Desire the greatest American play ever written?

"I'm in no position to make that kind of pronouncement," Previn replies, and then does so. "What's the competition, O'Neill and Miller? For me, it's the most remarkable combination of poetry and drama in America."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now