Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowIN SEARCH OF LINDBERGH

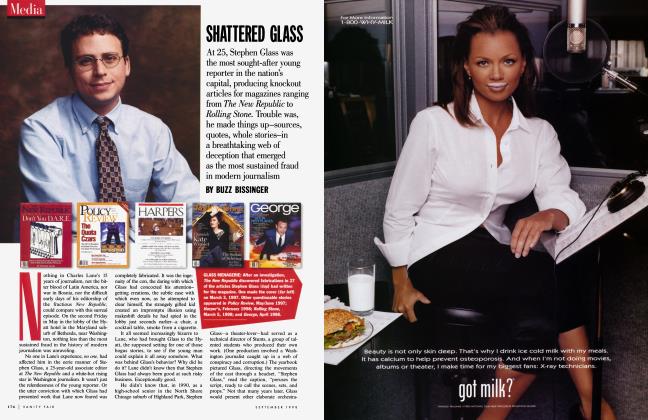

Writing the life of Charles Lindbergh took A. Scott Berg nine years. But with the help of the aviator's widow, Anne Morrow Lindbergh, Berg plumbed the mysteries of a hero turned victim turned villain, to produce a biography that will be one of the publishing events of the year

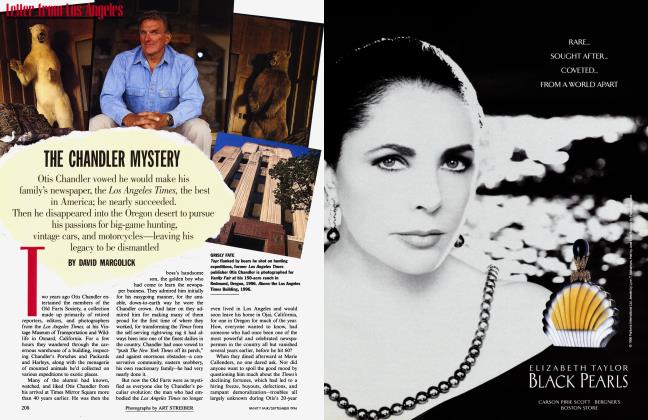

DAVID MARGOLICK

Books

It took A. Scott Berg nine years to chronicle the life of the great aviator Charles A. Lindbergh, roughly 1,000 times longer than it took his subject to fly from New York to Paris in 1927. Yet after all that time—and with Lindbergh, all 560 pages of it, due out next month—he can still vividly recall the skepticism with which two highly opinionated women initially reacted to the proposed project.

The first skeptic was his grandmother Rose Freedman, who headed the sisterhood of her synagogue in New Rochelle, New York. "What do you want to write about him for?" she asked in 1990, when Berg told her of his intentions. "He was quite awful about the Jews." She was referring to Lindbergh's well-known proGerman, isolationist sympathies during the late 1930s, which for many people stripped away much of the sheen from his heroic transatlantic flight and the sympathy generated by the 1932 kidnapping and murder of his infant son. The author of the 1978 National Book Award-winning biography, Max Perkins: Editor of Genius, and of Goldwyn, a 1989 biography of the film mogul, Berg knew that good biographers have to inhabit the worlds they write about; what his grandmother was really asking him was whether Lindbergh's world was one that Berg wanted to enter.

The other skeptic was then 83-year-old Anne Morrow Lindbergh, the aviator's widow. Without her cooperation—and without her permission to inspect Lindbergh's voluminous personal papers, supposedly off-limits until 50 years after her own death— there could be no book. "Why do you want to write about my husband?" she'd asked Berg only moments after they'd finally gotten together. "He's very much out of fashion, you know." The timing of Berg's book—for which Steven Spielberg has already bought the movie rights— seems peculiarly appropriate. Now that it's officially fin de siecle, it's surely safe to say that Lindbergh (who was born in 1902 and died in 1974) led one of the most extraordinary lives of the 20th century.

"He became one of the great heroes of the century with the flight, and then one of the great victims of the century with the kidnapping, and then one of the great villains of the century with his opposition to our entry into World War II," Berg said at his home in the Hollywood Hills. "He then became one of the great recluses of the century and remains one of the great enigmas of the century. What I learned is that Lindbergh's life was much more crowded and complicated and interesting than I realized, and full of surprises. Whenever I thought I could pin a label on him I found him making a 90-degree turn and doing something else."

Leon Edel, who spent one lifetime recording that of another— Henry James's—once wrote that, "even in death, the biographee makes demands on the biographer." Knowing that his life would be chronicled, Lindbergh—inventor, medical researcher, conservationist, airline executive, and Pulitzer Prize-winning writer in the second half of his life—saved everything. He combed through the prior books on himself—"quite terrible cut-and-paste jobs based on press clippings," Berg calls them. At 80 singlespaced pages, one memo he left behind was nearly book-length itself. "Lindbergh realized the day after his flight that they got the story all wrong, that he was going to be lied about all of his life, and so he left this archive, this incredible record," Berg said. "He kept every scrap and shred of paper that might document his life."

"About eight or nine times he left messages to me, his future biographer," Berg continued. "He would write on a letter, 'Do not believe this man. What this letter says is not true. Please see my diaries or Anne's diaries.' At times 1 thought he was trying to control me from the grave, and that perhaps there were things he didn't want me to see. I thought he was trying to shift my thinking to his way of thinking. But in every case I found him to be a truth-teller; sometimes his clarifications were less than flattering to him, but they were always the truth. It was done with a cold, objective sense of himself."

Berg, 48 years old, has literature, history, and Hollywood in his blood. While pregnant with him, his mother, Barbara, was reading F. Scott Fitzgerald; she not only gave him the novelist's middle name, but a first name (Andrew) that existed primarily to become an initial. ("She couldn't name a nice Jewish boy Francis, so I guess she started with the A's," Berg said.) Sure enough, when Berg got to F. Scott's alma mater (Princeton) in 1967, he became A. Scott.

Berg's father, Dick, is a screenwriter turned producer of mini-series and TV movies. His eldest brother, Jeff, is the chairman of International Creative Management. One younger brother, Tony, is an executive at Geffen Records, while the other, Rick, is a literary agent for screenwriters. His mother earned a master's degree in history from U.C.L.A. after her sons left home.

Jeff Berg said that his kid brother had always had an uncanny knack for setting goals and achieving them; this was someone, he noted, who decided while still in fifth grade that he would one day go to Princeton. "This character and this story have the scope and the sense of Americana that Spielberg would be drawn towards," he said. "I was surprised that he bought it without having read it, but I think that the purchase will turn out to be prescient."

Berg had long considered writing about Lindbergh. A book about "the Lone Eagle" fit neatly into his life's ambition: to capture, through the biographies of five or six luminaries, the sweep of 20th-century American history. But dozens of authors had sought access to the Lindbergh papers over the years; all had been turned down. Berg weighed writing other biographies: Tennessee Williams, Henry Luce. It was Phyllis Grann, C.E.O. of Putnam, who rekindled Berg's interest in Lindbergh. "I always wanted a real book on Lindbergh ... and I never found anyone who I thought was appropriate for the task," she said. But Berg was still wary after she approached him. "I said it was a brilliant idea—so brilliant that it can't be done," Berg recalled.

He nonetheless gave it a try. He wrote to Mrs. Lindbergh. He also wrote to her daughter Reeve Lindbergh, surmising— correctly, it turned out—that the youngest of the Lindberghs' then five surviving children would most likely be the family's unofficial archivist, spokesperson, and gatekeeper.

He enclosed both of his books, along with $30 in postage to forward them to wherever Anne Lindbergh happened to be—she had homes in Switzerland, Hawaii, and New England. He said he hesitated before sending along Goldwyn, for fear that the Lindberghs really were anti-Semitic. (In fact, in all of their discussions over the years, Berg said, the issue of his Jewishness never came up.) He also got help from a friend who shared a doctor with Mrs. Lindbergh: Katharine Hepburn, who wrote the widow a letter on his behalf.

In early 1990, after nine months of campaigning, Berg finally got Mrs. Lindbergh to agree to see him, at a friend's house in Florida. "This is going to sound spooky, but she is one of the few people I've ever met who have an aura," Berg said. "She is lit from within." He told her he would approach her husband with no preconceptions or agendas; he would let Lindbergh himself tell his story. After a few days, Mrs. Lindbergh began offering recollections. And a day or two later she handed Berg a light-blue envelope. Inside was a letter, written in legalese but in her own hand with a ballpoint pen, granting him access to all 2,000 boxes in the Lindbergh archives at various libraries. "I leaned over to hug her and said, 'Oh, Mrs. Lindbergh, this is the most beautiful letter I've ever read,'" Berg remembered. "Oh, it's really not much," replied Mrs. Lindbergh, whose own books, including Gift from the Sea, have sold millions of copies. "It's not the kind of writing I like to do."

When a second envelope arrived a few weeks later, Berg feared that she'd changed her mind. Not so. "You can't write about Charles without writing about me," the enclosed letter explained. And with that she granted Berg access to all of her papers, at Yale, including 60 years' worth of diaries, only small portions of which have ever been published.

Berg's journeys took him from the farm in Sweden where Lindbergh's grandfather left for America to the remote churchyard on Maui where Lindbergh is buried. At the American ambassador's residence in Paris, Berg saw the bed in which Lindbergh slept the night after his epic flight.

He also visited with the five Lindbergh children, who had inherited their parents' penchant for privacy; each seemed to live at the end of a long driveway off a country road miles from the nearest hamlet and hours from some makeshift airport. In Scotland, Berg tracked down Betty Gow, the nurse who in 1932 discovered that young Charles A. Lindbergh Jr. had been kidnapped. He interviewed General Norman Schwarzkopf, whose father, then head of the New Jersey State Police, had investigated the crime. When Anna Hauptmann, the octogenarian widow of Bruno Richard Hauptmann, the man executed for the deed, met Berg in a Pennsylvania diner, she came laden with papers ostensibly proving her husband's innocence. Within a few years, she was dead. Mrs. Lindbergh, now 92, is fading considerably.

Berg thinks that his Lindbergh, far more fleshed out and rounded off than the one known up to now, will prompt a reconsideration of this complex, mysterious man. Rose Freedman, who died in 1993, alas, will not read her grandson's latest handiwork. But were it possible, Berg believes, even she might have second thoughts.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now