Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now

'Did ya hear about John Kennedy Jr.?" Jim Carrey blurts out the question with all the jut-jawed hyper-mock-sincerity he's been frightening and delighting us with lo these many years. The empirically proven Funniest Man in the World is kidding, naturally. He is using the Kennedy crash to exemplify the Worst Excesses of the American media as he sees them. Not that Carrey hates the media or anything; it's just that, as the recent Kennedy overkill showed, "there's too many of them. It makes me want to vomit through my nose, I swear to God!" This being Jim Carrey, one recoils instinctively.

At this point Carrey can afford to write the media off as one giant emetic. Because more than any other contemporary star, he has forged a seemingly inviolable covenant with the multiplex masses. The kind of covenant that allows him to restrict rare interview chores to a duration of no more than two hours.

Even so, Carrey's fear that he has "nothing to say" almost stopped him, this fine morning, from leaving his house in the gilded Brentwood section of Los Angeles. ("Half a block from the bloody glove," he notes.) But he does submit to a 120-minute interview that takes place in a Winnebago that would need extensive remodeling before it could be described as "impersonal." The vehicle in question squats outside the type of high-powered L.A. photo facility where celebrities get their images burnished and buffed for mass consumption.

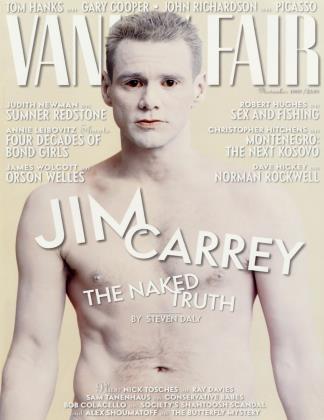

At this point in his life, Carrey has neither the need nor the desire to be burnished or buffed. "I was thinking it would be interesting to see an actor, you know, just absolutely show his age," he suggests upon arrival. "The pores and the crow's-feet around the eyes and maybe a zit or a blemish or whatever." He talks with perverse glee about the new "Nick Noltes" that traverse his forehead. The 37-year-old Carrey face may have lost some of its famous elasticity, but from more than six feet away, the off-handsome, six-foot-two actor manages to retain an impressively post-collegiate aspect, with his brush-cut hair, his mid-blue Levi's, his waffle-patterned T-shirt, and his purple Nikes.

Adding to Carrey's youthful mien is his giddy enthusiasm about the final cut of his forthcoming film, Man on the Moon, in which he portrays Andy Kaufman, the late situationist comedian (and incidental star of the 70s sitcom Taxi). Written by the duo who brought us The People vs. Larry Flynt, Scott Alexander and Larry Karaszewski, Man on the Moon attempts to explain one of the great, unknowable performers of modem times. As a stand-up comic, Kaufman did not look for laughs, preferring to test audience endurance with surreal experiments in banality: as "Foreign Man," he would tremulously tell the most hackneyed jokes, or he'd read aloud every word of The Great Gatsby. Unleashed on the network television audience, Kaufman became a fourth-wall demolition expert, famously disrupting ABC's live sketch show, Fridays, with his refusal to complete a skit. Ultimately, in a move that was deliberately ephemeral and recklessly damaging to his career, he took to wrestling women, then became embroiled in a feud with the wrestling star Jerry Lawler. The fact that Kaufman never, ever broke character or let anyone in on the gag guaranteed him cult immortality when, at 35, he died of lung cancer. In fact, many even believed that Kaufman's 1984 death was itself really just a gag.

Two Kaufman biographies will hit stores before Man on the Moon's Christmas release, and R.E.M. has recorded the soundtrack. This is officially Kaufman season.

Director Milos Forman reportedly had such heavy hitters as Sean Penn, Edward Norton, and Kevin Spacey lining up to play Kaufman, but when Forman saw Jim Carrey's Kaufman there was no doubt. The part would also give Carrey the chance to confront his detractors with a new level of actorly commitment. Never again would a co-star be able to tell Carrey, as Tommy Lee Jones reportedly did on 1995's Batman Forever, "You're from cabaret and I'm a trained classical actor."

It's a wonderful thing to get an Oscar. But I really don't like the idea of kissing people to get it.

Months of Andy Kaufman research and interviews with the comedian's intimates were followed by a complete physical transformation by Carrey. That, however, was just the beginning. He explains the rest of the process with the third-person detachment that is the prerogative of the Truly Great in Hollywood. "You could not access Jim Carrey on the set. Andy was there and Tony was there—if you see what I'm saying." Kaufman, that is, and Tony Clifton, the ineptly chauvinistic lounge-act

character that Kaufman would assume when he wanted to swap his passive shtick for something more aggressive.

From Milos Forman on down, Carrey's Man on the Moon colleagues were obliged to address him as "Andy" or "Tony" during the 87 days of filming last year. "I'm sure there were people there that looked at me at first like I was some frickin' actor who's in his little head trip or whatever," Carrey says. "But that was what Andy did—I don't think I'd do it for anything else. He lived the character, and you believed that either he was nuts or he really was this character. There was no, like, 'You know, I'm not insane.' There's no apology to it, and it was so freeing."

For James Eugene Carrey, freedom means escape from popular expectations of plastic-fantastic mugging, talking asses, and "Alll rrrighty, then!!!" The last time he went straight, playing the titular dupe in 1998's The Truman Show, popular opinion had it that he deserved at least an Oscar nomination. Logic prevailed, however. Because Carrey was essentially just an understated cipher in director Peter Weir's heavy-handed media satire, he was ultimately stiff-armed by Academy voters.

This time he should get a shot at the statuette. Man on the Moon is a pleasingly anachronistic, actor-friendly vehicle, and the erstwhile Ace Ventura delivers a performance that would do credit to any aspiring De Niro or Nicholson. The fact that a non-comedy about a cultish non-comedian might be a little challenging for dumbed-down movie audiences need not detain Carrey. He has just finished work on Me, Myself and Irene, another comedy from the surefire Farrelly brothers (Dumb & Dumber, There's Something About Mary): in strange congruence with Peter Farrelly's 1998 statement that Carrey has a "very commercial form of mental illness," this one is about a man whose two split personalities compete for the same girl.

Naturally, Carrey denies that he's interested in something as sordid as an Oscar hunt. "It's a wonderful thing to get an Oscar," he says. "But I really don't like the idea of kissing people and changing myself to get it. I would do that and that and that—start trying to pick my parts for an Oscar. You have to have the talent, obviously, but you definitely have to go through a bit of a gauntlet to get it. You know, I know they're doing the monkey dance; there is a plan, and, believe me, I know from people who are Very high Up: they say they're doing the monkey dance."

Milos Forman never met Andy Kaufman, but he became fixated on him after witnessing a Los Angeles comedy-club performance in the mid-70s. Forman and his friend Buck Henry swapped incredulous glances as Kaufman tested the crowd's boredom threshold by explaining, and then reading in full, an unremarkable short story. Two decades later, Forman ran into Kaufman's Taxi co-star (turned movie producer) Danny DeVito at Michael Douglas's 50th-birthday party in New York and raised the idea of a film about Kaufman.

The casting of Man on the Moon (named after the R.E.M. song about Kaufman) showed that Forman's Oscar-winning 1975 film, One Flew over the Cuckoo's Nest (in which DeVito co-starred), had left him with an abiding taste for the madhouse. Forman created a through-the-looking-glass world in which the real and the unreal collided at random: some Kaufman contemporaries play themselves (wrestler Jerry Lawler, David Letterman, Saturday Night Live's Lome Michaels, Taxi cast members), while others mingle with those they are portraying. DeVito, for instance, plays Kaufman's manager, George Shapiro, who in turn plays comedyclub owner Budd Friedmann. Among the Kaufman intimates and relatives present was Kaufman's longtime girlfriend, Lynne Margulies, who watched as Courtney Love reenacted her life with Andy.

All of which seemed manageable until the World's Funniest Man came on board in full Method mode. Depending on the day, Forman, 67, might find himself facing off against the oafish, odiferous Tony Clifton or be forced to lure a skittish Kaufman out of his trailer. "It took me a little time to get used to it," says the director. "But it was a wonderful game to play."

Rumors from the Man on the Moon set confirmed that "Andy" was back, in all his obsessive-compulsive glory. "Tony" smeared visiting Universal executives with Limburger cheese, berated Forman's pal Elton John for being a half-assed look-alike, and made Forman address him through a Hell's Angel called Chuck Zito. One time Clifton and some Angel buddies sprayed graffiti all over Chasen's, the famous Hollywood restaurant, which served as one of the sets.

Comedy doesn't depress me. Love depresses me.

When tabloids reported that the brutish wrestler Jerry Lawler had assaulted Carrey while re-enacting his notorious real-life attack on Kaufman in 1982, the whole affair took on the distinct whiff of P.R. But according to Judd Apatow, a longtime Carrey collaborator and certified Kaufmaniac, the reality wall was broached with some force.

"The climax of the scene is Jerry Lawler smacking Jim on the face and Jim flying off the chair," says Apatow. "Before they did it, I hear Jerry Lawler say to Milos Forman, 'Should I really hit him?' And Milos says, 'Softly.' Then you see Jim lean over to Jerry Lawler, and he basically says, 'Hit me as hard as you can.'

"They got to that moment in the scene, and Jerry Lawler just cracked Jim in the head as hard as I've ever seen anybody get hit—it wasn't miked, so you just heard it in an empty auditorium, this crack sound. The inside of Jim's mouth was just all cut up and bleeding afterwards. And as we're watching it on the video, he was, like, 'Isn't it great? Doesn't that look brutal?"'

Early in Man on the Moon, we see young Andy Kaufman hosting an imaginary TV show in his bedroom. A film about Jim Carrey might start in a similarly solipsistic fashion: the Funniest-Man-to-Be used to sit in a tiny closet, scrawling out reams of his own songs and poems. But whereas Kaufman's evolution into self-immolating genius and terminal enigma required the Pirandelloesque machinations of Milos Forman, Carrey's star trip makes for more melodramatic, less demanding material. Let us imagine it as, say, a movie on the USA Network.

The title sequence of Where Does Comedy Come From: The Jim Carrey Story (tonight, after La Femme Nikita) features faux-Super 8 footage of the Carrey clan, in hazy suburban-Toronto idyll. Conducting the mirth is sax-playing patriarch Percy Carrey. The laughter fades when he has to sell his sax to pay hospital bills when Carrey's sister is bom. Percy gets an accounting job—then loses it at the age of 51. A grim spiral of downward mobility sees the entire family forced to take jobs as janitors in a tire-rim factory before, bitter and disillusioned, they quit work to live in a tent and a VW camper. "Living in a van, dah, dah, dah, dah, dah," says Carrey today. "It can't be talked about anymore. It's so frickin' boring."

To him, perhaps. But to the director of our imaginary cable movie, this is a key to the protean suffering of a comedy superstar in the making. We've already seen Jim entertaining his sick mother with a welter of comic impressions, and aping his alcoholic grandparents for the amusement of his brother and two sisters. Now the gangly 15year-old high-school dropout decides to try his luck at Toronto's Yuk Yuks comedy club. A handheld camera follows Carrey's hokey routine to a silent grave; his ill-chosen yellow polyester suit flares up sickeningly in the footlights.

Two years later, Carrey returns with a new act, co-written with his dad, that wins over crowds and reviewers. He moves to L.A. and, with preposterously good fortune, snags the role of preppy dupe Skip Tarkenton in The Duck Factory, an unremarkable but well-regarded 1984 sitcom about an animation studio. He brings his mom and dad down to L.A., but NBC cancels the show after just 13 episodes, and he has to send his parents back home. Carrey now calls that setback "one of the pivotal moments of my life and something I still have a major pain and guilt over."

His 150-strong repertoire of impressions (which include Bruce Dern and a postnuclear Elvis) continues to bring lucrative rewards, such as opening for Rodney Dangerfield. One slight problem: Carrey doesn't want to be the kind of guy who opens for Rodney Dangerfield. So around 1985, he abruptly ends his impressionist period and starts taking acting lessons. "Everybody who knew me said, 'What are you doing?'" recalls Carrey. '"Play Vegas! Be the greatest impressionist in the world! u got a milliondollar industry in your lap!"'

At the time, Carrey is living with his girlfriend, Melissa Womer, in a tiny apartment in Koreatown. They met when she was waitressing at L.A.'s Comedy Store. The couple marries in March 1987; their daughter, Jane, is bom that September as Carrey's bank account runs dry. "I didn't file bankruptcy, but I went tits up," he says. "I'd gone from being this popular singing-impressionist guy to like—nothing. "

So he returns to the clubs and modest movie roles trickle in, among them 1989's kitschy Earth Girls Are Easy. Co-star Damon Wayans helps him become the prominent white face on his brother Keenen Ivory Wayans's early-90s hit TV series, In Living Color. This is "James" Carrey's second big chance, and rarely has any performer been more ready for prime time—he becomes the ensemble show's breakout star. The year 1994 brings Carrey his first leading-man movie roles, and, astonishingly, he hits the jackpot with three broader-than-CinemaScope sleeper comedies in a one-year span: Ace Ventura: Pet Detective, The Mask, and Dumb & Dumber. The fact that each part of this farcical trifecta is directed by an unknown (respectively, Tom Shadyac, Charles Russell, and Peter Farrelly) tells us that Carrey is a force of nature, the Michael Jordan of physical comedy. Even more than on In Living Color, Carrey touches some primeval nerve by pushing his own geeky ultra-whiteness to the sociopathic brink.

Our basic-cable picture ratifies Jim Carrey's arrival as a funnyman with a barnstorming montage of his movie triumphs. Between 1994 and 1995, each of those first three hits earns more than $100 million, and his salary shoots from $350,000 (Ace Ventura: Pet Detective) to $7 million (Dumb & Dumber). But all is not well in the Carrey household: after midnight, ham turns to Hamlet, prowling the house in the throes of dark moods and restless drives. There is strain on Carrey's marriage to Melissa, and a messy 1994 divorce. A romance with perky Dumb & Dumber co-star Lauren Holly produces short-lived nuptials in 1996.

This chapter of the Carrey story ends in a wee-hours diner, with our protagonist awaiting reviews of The Cable Guy, his attempt to escape goofball servitude. Judd Apatow, the film's producer, brings in the early editions, and they're unanimous. "Before the movie ever came out it was defeated!" says Carrey, still chafing after all these years. "It's very hard for a studio, when they're sitting there with this big pile of gold beside them—which is selling me as a silly, goofy guy. The reality of the movie is I'm kind of creepy. If you're going to do it, don't apologize for it." Reports of Carrey's record-breaking $20 million salary hardly help matters.

Some revisionists would agree that The Cable Guy (directed by Ben Stiller) was misunderstood, but as the addled cable installer Chip Douglas befriends and ultimately terrorizes a client (played by Matthew Broderick), the film's tone wavers wildly. And Carrey's normally impeccable comic judgment falters as he endows Chip with a speech impediment of Adam Sandleresque proportions. Despite some compelling flashes of malevolence from Carrey, The Cable Guy is, uniquely among his movies, not very funny.

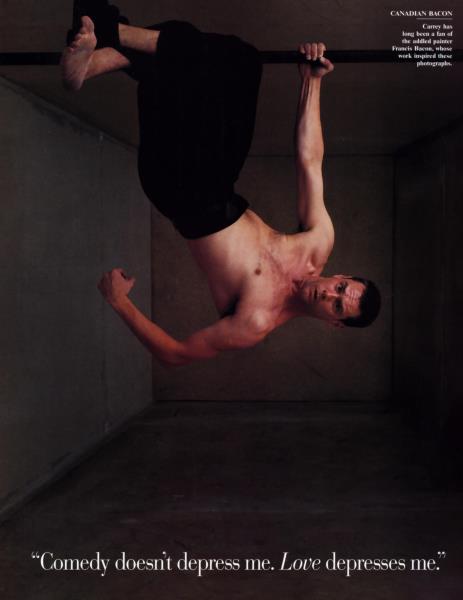

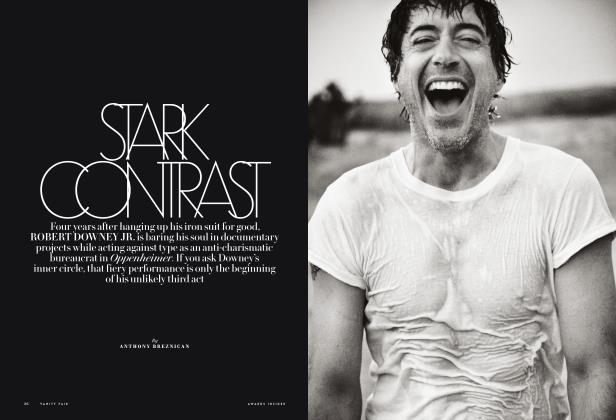

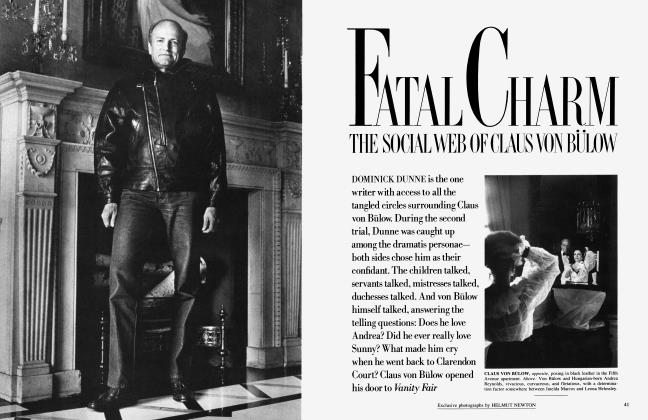

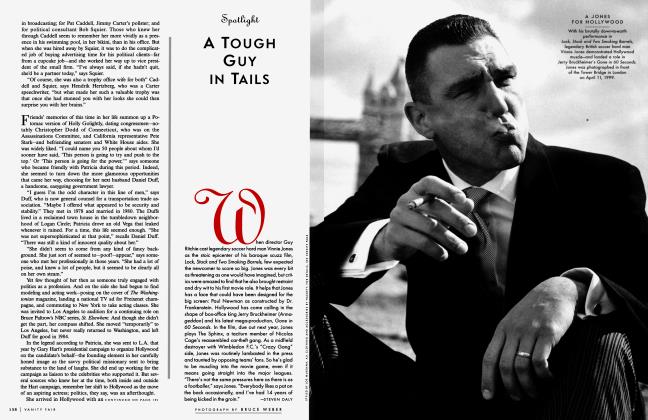

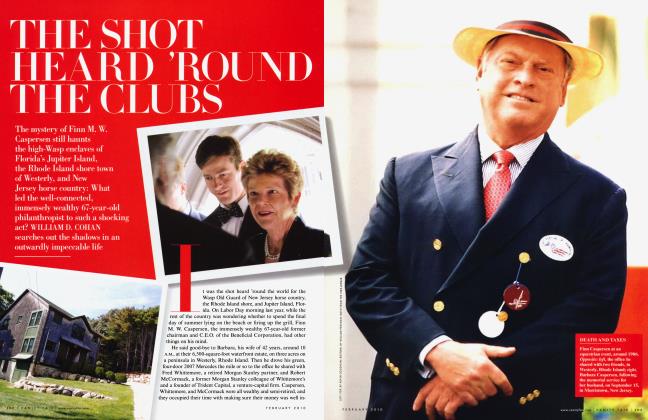

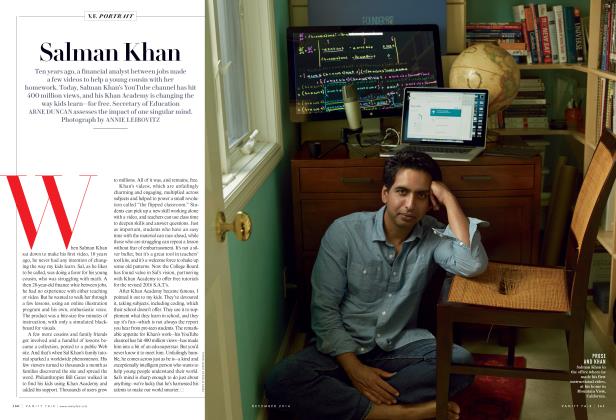

CANADIAN BACON Carrey has long been a fan of the addled painter Francis Bacon, whose work inspired these photographs.

CANADIAN BACON Carrey has long been a fan of the addled painter Francis Bacon, whose work inspired these photographs.

When R.E.M. front man Michael Stipe heard that America's Funniest Man was set to play Andy Kaufman, his reaction was unequivocal. "I called Milos and railed against Carrey," says Stipe. "I didn't know if he would be able to put aside the kind of Carrey-isms that I had seen in his past work."

The singer's rush to judgment was shared by many hard-core Kaufmanistas, for whom Andy is a comedic Che Guevara: an ideological martyr who died untainted by corruption or compromise. In 1995, Brian Momchilov launched the Internet's first "Andy Kaufman Home Page," and he recalls the reaction when Carrey's name was first linked to Kaufman's. "A lot of folks said, 'This is the worst—he's going to wreck it,'" says Momchilov, who lives in Michigan and works for the Department of Defense. He has recently seen the consensus fall into line with Michael Stipe's ultimate verdict on Carrey's Kaufman portrayal: "totally brilliant," and according to Momchilov, the word of mouth is effusive.

Nevertheless, there remains a curious tension between actor and subject. Carrey cites Kaufman as his inspiration for his stand-up improvisational period, and for his occasional stunts since then, such as his appearance at this year's MTV Movie Awards, where he "played" a kind of hybrid of Duane Allman and Jim Morrison. At this year's Academy Awards, the nomination-less Carrey brought the show to a halt, thanks to his indulgent "I'm not bitter" speech, which veered from angry to lachrymose. But those who know about these things say that Carrey's loopy gesture ultimately guaranteed the goodwill of Academy voters next time around. (In other words, it was a variant of the Oscar "monkey dance" that Carrey so despises.) When Carrey invokes the spirit of Andy and smears cheese on executives, he knows that his action does not risk a sanction from studio or producer. His madness has a mandate. Plus, in a self-conscious act that seems at odds with the Kaufman spirit, Carrey intends to produce and direct a Man on the Moon "making of" documentary, using on-set footage shot by Lynne Margulies.

Then again, which contemporary performer could survive comparison to Andy Kaufman, a holy fool who makes every other comic look like an attention-craving slave of Mammon? Those were different times. "Andy was more bohemian," says his sidekick, Bob Zmuda, who went on to found the Comic Relief charity. "Andy was a real product of the 60s."

The most cursory glance at Carrey's and Kaufman's respective backgrounds further explains the gulf between their sensibilities. While Carrey's performing life was launched by poverty, Kaufman enjoyed a comfortable upbringing in Great Neck, Long Island. Carrey was the country boy who said "frickin"' and feared failure; Kaufman embraced it: he made his audience drown in flop sweat.

Carrey's need for financial and emotional approval was never greater than when In Living Color gave him his second—and maybe last—chance. Carrey paid Judd Apatow out of his own pocket to write material that might help him compete for airtime. And according to one staffer, "He would endlessly be doing shtick in the hallways, for the secretaries. There's not a moment when he didn't need an emotional B12 shot."

It is precisely that kind of desperation that has put this edgy performer within sight of a goal once described by comanager Eric Gold: "Tom Hanks's career." Yet the very mention of Hanks causes Carrey's "Nick Noltes" to stand out. "You know, Tom does great stuff," he says. "But every time he goes out now, he has to be rock-solid America Man, and I kind of want to see him go nuts. He's now Mount Rushmore for people, and I don't want to be that. I mean, I can be a stand-up guy, and I am, but I just see too much irony and weirdness in the world that I can't shut up. I can't not say something."

If anyone needed definitive evidence that Jim Carrey is more than a turbocharged vaudevillian, one could look to the final episode of Gary Shandling's incandescent show-business satire on HBO, The Larry Sanders Show. As the first of Sanders's very special guests, Carrey serenades the departing host with a rendition of "And I Am Telling You I'm Not Going," the Sturm und Funk showstopper from Dreamgirls. This skinny white boy slams into the challenging number at full tilt, Apollo Theatre-style. Incredulous applause fades into the commercial break, and Carrey edges toward Shandling. He coolly informs Shandling that he's here for promotional purposes only. "What are you going to do now?," Carrey asks. "Movies? I'll crush you."

Over the years, the sophisticated likes of David Duchovny, Warren Beatty, and Sharon Stone tossed their vanities on Shandling's bonfire, contributing brilliant acts of self-loathing, self-revelation, and self-parody. But Carrey's exhilarating combination of vocal prowess and wanton neediness outshone them all. When Carrey agreed to appear on The Larry Sanders Show, he told Judd Apatow (who was then a producer there) that his would have to be the best cameo the show had ever seen. "Oh, I know he was serious," says Apatow. "That's how Jim approaches everything."

Talk to those who have worked with Carrey and you'll soon tire of hearing about the man's stamina. "He'll bum you out," says Bobby Farrelly. "There comes a time when it's the end of the working day and it's, like, 'All right, well, let's go.' But Jim would love to do 10 more takes. For him, it's like going down a water slide—you want to just race back up and do it again."

As the scenes from his first marriage attest, Carrey does not relax when the cameras are off. His physical endurance is matched by a level of mental application that, he allows, might come from the "feeling of unfinishedness" that his interrupted schooling gave him. This, in turn, spawned an autodidactic zeal that has proved surprisingly useful over the years. "When I was working the comedy clubs for 15 years before anything happened, I laid on my bed at night, trying to figure out the psyche of the audience," says Carrey. "Trying to figure out what people need—what serves them. I mean, I could sit here and dissect what I think comedy is and make it really boring for everybody, but I know what it is.

"I pulled it apart like—I'm not saying I'm as smart as this guy, but, you know, Freud pulled it apart. Freud talks about jokes being judgments, and that's what they are: the job of a comic is to judge. I can get into all this stuff and break it down to why an audience is attracted to one person and not to another person. I know it."

Carrey sometimes thinks of comedy as a lethal weapon. As his Larry Sanders spot suggested, our lovable goofball is—like most great comedians—an avid connoisseur of human frailty. "There are times in my shower where I'll think of a person and I'll be mad at them," he says. "And I'll arm myself with 20 good things if they ever say anything to me. That's what comedians do: prepare themselves for war."

'I am," says Jim Carrey, "one of the top five actors. Every director who's worth their salt wants to work with me. I have the best scripts in town offered to me."

Carrey isn't going to war with anyone, or reprising his toxic bit from The Larry Sanders Show. He is merely reciting the "affirmation" he gave himself years ago as he sat up on L.A.'s Mulholland Drive, in the decaying Toyota Supra that he'd bought with leftover sitcom money. There he wrote himself a check inscribed: "For acting services rendered, $10 million." He dated it Thanksgiving 1995.

Which sets up the most unbearably bathetic moment in our notional Carrey movie. We see Carrey putting the check into his father's pocket as he lies in his coffin. (Carrey's mother has died three years earlier.) It is July 1994, and in the wake of Ace Ventura: Pet Detective, Carrey has signed on to do Dumb & Dumber for $7 million.

This unlikely series of events actually happened to Jim Carrey, who doggedly attributes all the good things in his life to the affirmations that he derives from a combo platter of self-help and spiritual literature. "Jon Kabat-Zinn's Wherever You Go, There You Are, Norman Vincent Peale—all that stuff is good." He excitedly mentions a book that Steve Martin gave him called The Drama of the Gifted Child. It's about what happens when "the family's hopes and dreams are pinned on the special child— that affects a person in a major way."

"Jim lives the examined life," says Eric Gold. And as the Catholic-raised Carrey explains, his endless seeking does have a concrete payoff. "I find that a lot of the times if I let myself go unstimulated by positive things I'll get into a funk, start to believe that nothing's worth it—whatever. So I'm a big believer in affirming. You know, nothing happened before I affirmed it in my life. I haven't been in a black hole for a long time."

For some years now, the biggest anxiety threatening to fill the void has been not lack of approval but rather a surplus of the wrong kind of love. By responding so strongly to Carrey's rampant neediness, the public has, in a sense, cursed him. "The fact is, at least in the next 10 years, I will not be able to walk out of my house without somebody knowing who I am," says Carrey. "It makes you self-conscious. When I leave the house, I'm Jim Carrey, and I have to be somewhat of a diplomat, even if I'm in a shit mood. You pull a lot of extra responsibility in your life by being this type of person, you know.

"And if people go, 'u asked for it,' yeah, you did. You did ask for it, but no one knows what it is till you're there. I'm an astronaut, and there are only a few people in this world who know what I know and know how it feels to be who I am."

It is suddenly evident that Carrey might not be joking when he says that instead of seeing a shrink he has recently been "stocking it up." Hamlet is on the ramparts again, with a soliloquy at the ready. "I try and I try, and I'll go out to the crowd and I'll do 20, 30 autographs," he says. "And the 31st person will call me an asshole after I've just given it all out. I've gone home sobbing some days because of that 31st person. It's a no-win situation."

The suggestion that depression might just be the flip side of the comedian's covenant with his public is given short shrift. "Comedy doesn't depress me," says Carrey, smiling faintly. "Love depresses me. I don't have anyone special in my life at all, and it's a drag. It's a very difficult proposition for a person like me, because I get girls who fall in love with me in an hour and want it all. I'm a very normal person, you know, and I don't want those excesses. I've gone through periods of my life where I thought it would be cool to have all that stuff. But I'm not a player, I guess—never have been. All I want is one good woman. That's it. And I need to be a good man. I'm not the easiest person, you know."

Carrey's Man on the Moon co-star Courtney Love begs to differ. "I have to tell you: I really just fell in love with him," she says. "I mean, not in the literal, I'm-going-to-get-married-to-him sense. . . . Underneath him, there is a lot of depth. And a lot of sexiness—I mean, many, many people think Jim's sexy. But I mean sexy in a Tantric way—a sort of deep, soulful, and almost dark way."

Jim Carrey wasn't always possessed of Tantric sex appeal or a particularly examined life. Back in his L.A. comedy-club days, he was a brash Young Turk who had formed a mutual-admiration society with Sam Kinison, the stand-up screamer who died in 1992. "Night after night, we'd go out, and there's fists flying, or whatever," Carrey recalls. And then there were the drugs. "I experimented with everything, very briefly," he admits. "I had friends who went, like, 'What are you doing, man?' And I just went, 'Yeah, you're right—it's not me.'"

Carrey moved on to a group of friends that included Francis Ford Coppola's son Roman, actor Cary Elwes, and Nicolas Cage. When their habit of handing out a jokey award to the highest-achieving member began to get tired (due to Cage's and Carrey's ascent to mega-stardom), Carrey suggested a change of pace. "Jim was always big on the idea of having a book club," says Cage, who acted opposite Carrey in 1986's Peggy Sue Got Married. "It's a sign of Jim's quest for knowledge. He is one of the smartest guys I know."

These days, Carrey tends to conduct his quest in private. "I'm not a shut-in, but I'm a bit of a loner," he says. "I disappear for long periods of time. I just go, 'I'm now Solitary Man, and I don't want to deal with anybody.'"

When he's between films, Carrey will occasionally slip out of his gates on his beloved Harley, helmet visor pulled down over that iconically malleable mug. Mostly, though, he's happy to stay home with his daughter, or maybe play tennis with a friend. Some days he'll let his dogs, George and Hazel (Great Dane and chocolate Lab), have the run of his 11,000-square-foot house while he quietly slips into his pool. "I call it the river Jordan," says Carrey. "Because that's where I swim and I float and I talk to God and I do whatever. And a lot of good things have happened there."

Adrift in ennui deluxe, Carrey sometimes feels like quitting the business altogether, just as he did during his impressionist days. "I think I could go away tomorrow," says the Funniest Multimillionaire. "I've already accomplished something. It would be a new phase of life, and something else would happen. It's such a selfish business that sometimes I get sick of myself. I'm going to have to, at some point, drop this stuff and do something that's more of a service—something hands-on, whatever it is. I'm talking about, like, painting in malls or something for a living."

This sublimely Kaufman-like thought hangs in the air. For a non-therapy patient who has "nothing to say," Carrey has done pretty well this morning, and has rarely fallen back on "Carrey-isms." But, as in therapy, the session must end before the final breakthrough comes. Only this time, the person calling time is his personal publicist.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now