Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

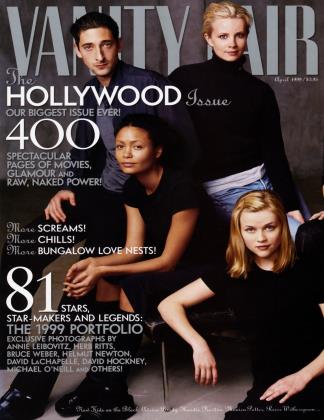

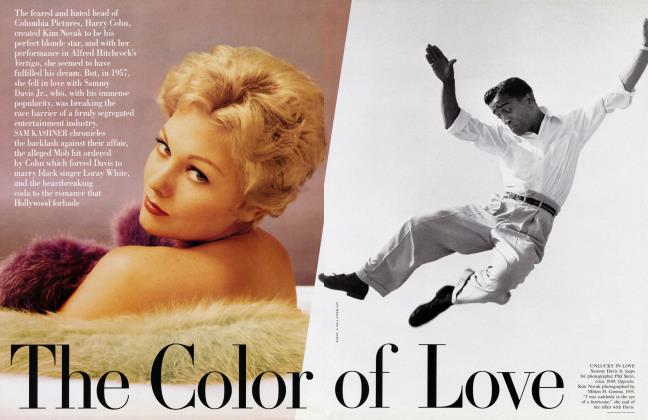

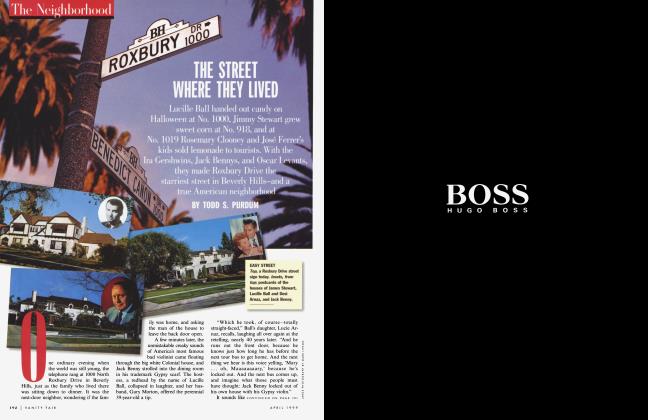

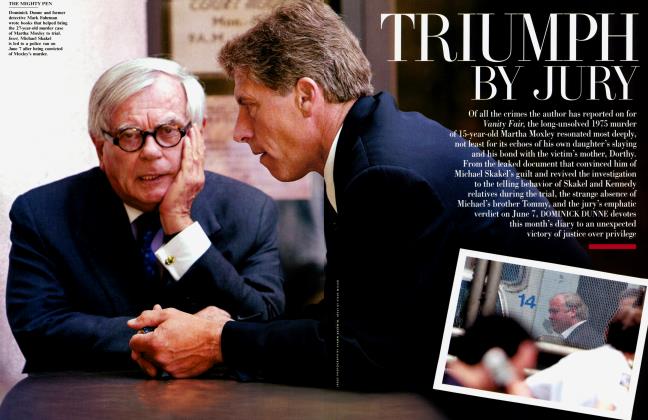

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowMike Romanoff claimed he was a Russian prince, educated at Eton and Oxford, and a former commander of a Cossack regiment. In reality, he was a tailor's son from Vilna who spent miserable years as a deportee, con man, and thief. But his ultimate identity was forged by Romanoff’s, the legendary Beverly Hills restaurant he opened in 1939 with the backing of Jock Whitney, Alfred Vanderbilt, and Laurance Rockefeller. DOMINICK DUNNE recalls a man whose audacious style won him the hand of the elegant Gloria Lister, the friendship of Clark Gable, Sam Goldwyn, and Humphrey Bogart, and the status of Hollywood royalty

April 1999 Dominick DunneMike Romanoff claimed he was a Russian prince, educated at Eton and Oxford, and a former commander of a Cossack regiment. In reality, he was a tailor's son from Vilna who spent miserable years as a deportee, con man, and thief. But his ultimate identity was forged by Romanoff’s, the legendary Beverly Hills restaurant he opened in 1939 with the backing of Jock Whitney, Alfred Vanderbilt, and Laurance Rockefeller. DOMINICK DUNNE recalls a man whose audacious style won him the hand of the elegant Gloria Lister, the friendship of Clark Gable, Sam Goldwyn, and Humphrey Bogart, and the status of Hollywood royalty

April 1999 Dominick Dunne'My mother was a Romanoff and my father an Obolenski. Yes, I trained at Eton and Oxford and served as an officer in both the British and Russian armies. I was still at Oxford when the war broke out. My schoolmates were all going down, so I asked my emperor’s permission to fight with them. I was in the Tenth Hussars for two years, when my emperor called me home to command a regiment of Cossacks.”

There is not a single word of truth in that statement, part of an interview which appeared in the St. Louis Star on March 15, 1923. Fabrication and impersonation are part of this story, and the hero might best be described as an impostor. Prince Michael Romanoff, the renowned Beverly Hills restaurateur with the imperial manner and such best friends as Spencer Tracy, Clark Gable, Humphrey Bogart, and Frank Sinatra, was born Hershel Geguzin, the sixth child of Yiddish-speaking parents, in Mina, a Russian territory which subsequently became part of Poland and then Lithuania. His birth occurred several months after the death of his father, a tailor, who had intervened as peacemaker in a street fight during a visit to Warsaw. His mother, Hinde, took over her husband’s business, which consisted primarily of making uniforms for the local police, and left the bringing up of Hershel to her oldest daughter, Olga. From the beginning the boy was a truant and a runaway, a cause for concern to his already overburdened mother. In 1900, when Joseph Bloomberg, a cousin or uncle—depending on which version you come across—decided to immigrate to America with his family, Hinde prevailed upon him to take Hershel along. He was 6 or 8 or 10 years old—as with everything else in his life, versions vary. But one thing was certain: he would never return to Vilna.

The first time I went to dinner at Romanoff’s, Beverly Hills’ fabled bastion of the rich, powerful, and famous of the film industry, it was everything I had ever heard it was going to be. Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall, looking gorgeous, were seated to the left as I entered the main room. Nearby was the flame-haired MGM star Greer Garson with her oil-rich Texas husband, Buddy Fogelson, and at another table was the glamorous Mrs. Billy Wilder, the wife of the famous director, in a party that included the actor Charles Laughton and Randolph Churchill, the son of the former prime minister of England. Back then, from the mid-50s to the early 60s, when the restaurant closed, it was always like that. “Star-studded” was the term the gossip columns invariably used to describe Romanoff’s.

Equal in stature to the stars, though, was the ringmaster of the enterprise, Prince Michael Romanoff, a bona fide celebrity himself, whose feats of bravura and derring-do from immigrant child to Russian prince had entertained the public for a quarter of a century and been documented by Alva Johnston in a five-part profile in The New Yorker in 1932. Unhandsome and small of stature, he was nevertheless a great favorite with the ladies, right up to his past-middle-age marriage. It was Mike who arranged for Marilyn Monroe to meet Johnny Hyde, the William Morris agent, one day at lunch in the restaurant, and it was Johnny Hyde who turned Marilyn into a star. Mike’s perfect grace and style immediately drew attention away from his physical shortcomings. There he stood in the center of things, greeting his patrons in a deep-baritone, English-accented aristocratic voice, addressing his pals as “old boy,” kissing the hands of favored ladies, enjoying himself immensely, as if it were a wonderful party he was perpetually giving, and the famous never tired of wanting to be where he was. He was one of them. He belonged. He was part of the social world of the people he seated at the best tables. A lot of private shenanigans took place at Romanoff’s, in both business and romantic areas, but Mike never leaked a word to Hedda Hopper or Louella Parsons, the rival gossipists of the period, who lunched and dined there themselves.

I never saw him when he wasn’t wonderfully dressed, even for playing croquet on weekends at Samuel Goldwyn’s estate, where he was a regular. There seemed to be no occasion for which he didn’t have the perfect outfit. It was Mike Romanoff who taught Clark Gable how to dress the way a dashing movie star should. When Mike smoked, he made a minor ritual of the process, in the way he took a cigarette from his gold case, tapped it, lit it with a gold lighter, and then curved his finger around it in a unique manner as he inhaled with the utmost satisfaction. His presence and personality were so compelling that the restaurant lost its luster on the rare nights he was not there.

By the time the Bloomberg family settled in New York, Joseph Bloomberg was out of patience with his mischievous, willful relative. As for Hershel, the feeling was mutual. He was placed in a Hebrew orphanage, the first of six institutions, of various denominations and in various locales, that he would run away from. He was branded as incorrigible. Somewhere along the way, one of the institutions renamed him Harry Gerguson, a name he despised, but it stayed with him throughout his youth, until he emerged under a number of aliases suggesting far grander pedigree—Arthur Wellesley, Willoughby de Burke, Count Gladstone.

He endured years of miserable living as a runaway, a stowaway, a jailbird, a check bouncer, a deportee, an escapee from Ellis Island, a fraud, a confidence man, and even a thief. He often slept on floors, in doorways, on park benches, and in barns. Early on he felt an attraction to people of quality, and he had an ability to make himself agreeable to them. Little and likable, he was the kind of bad boy people wanted to help. Social ladies who did charity work in orphanages took him under their wing, having him for weekends at their houses in the country. A gifted mimic, he could entertain his betters with astonishing stories. An early benefactor said about him, “He was one of the most convincing liars you ever met.” In these situations, the orphan who would become a prince saw the kind of life he wanted to live. The problem was getting there.

Later, Mike would claim that he had attended Eton, Oxford, Heidelberg, Harvard, Yale, and Princeton, although Oxford figured most importantly in his tales. It is possible that he may have been employed for a time as the valet of a rich American who attended the English university. He also claimed at different times that he had killed a German nobleman in a duel, that he had spent World War I on the Eastern front as a Cossack colonel, that he had been in the Foreign Legion and with Field Marshal Edmund Allenby in Palestine. Along the way, he became a great reader of Russian history and developed a special fascination with the fate of Russia’s royal family. As the Russian aristocracy and nobility scattered and fell into total disarray, Harry Gerguson’s chances of detection were lessened. On an ocean liner crossing the Atlantic, his impersonation of a nephew of the late czar Nicholas of Russia endeared him to the firstclass passengers until he was unmasked as a stowaway by the ship’s captain and led off by the police when the ship docked in New York. Journalists noted that he was never more princely than when he was being exposed as a fraud. He was taken to Ellis Island, from which he made a highly publicized escape that marked the beginning of his celebrity.

Another time he passed himself off as the American artist Rockwell Kent, who had befriended him during one of his frequent down-and-out periods by giving him lodging and employment. British tailors, boot-makers, jewelers, and tobacconists had him arrested and jailed four times on charges of fraud, ignoring his protestations that Russian nobles settled their accounts with tradespeople only once a year. My favorite story about him is that, during one of his longer incarcerations, he would carry a smart walking stick during the exercise period. Once, he swiped gold-backed military brushes from Paul Mellon, of the Pittsburgh Mellons, and later insisted that the monogrammed initials “PM.” on them stood for Prince Michael.

Hollywood was where the prince belonged, although 1927 foray there as a technical adviser on a film about pre-revolution Russia had proved mortifying when a former Russian general also working on the film exposed him as a fraud: Mike had consistently refused to speak to him in Russian, a language he had never mastered. Now, in 1936, having become the impostor prince for good, he was ready to return. On his way west, he passed through New Orleans and dined at Antoine’s, the city’s best restaurant. Although he was disappointed with his meal, the experience gave him an idea for his future life. He thought, A restaurant is something I could do. He understood that friendships develop over food and wine, and by then he knew enough people to get things organized.

He lived in Hollywood over a shop bearing a sign saying, ROOMS FOR RENT $2.50 A WEEK. He shared his room with Prince Youka Troubetzkoy, who had no money but wore great clothes. In years to come, Troubetzkoy went on to marry Marcia Stranahan, the Champion-spark-plug heiress, while his brother Prince Igor Troubetzkoy went on to become one of the many husbands of Barbara Hutton, the Woolworth Fiveand-Dime heiress. Mike subsequently shared better apartments with such early Hollywood figures as Pat DeCicco, an actors’ agent, who became the first husband of the 17-year-old heiress Gloria Vanderbilt, and then with DeCicco’s cousin Cubby Broccoli, who became rich and famous as the producer of the James Bond films.

“I did not hit Randolph Churchill in the face with a fish that night at Romanoff's, said Audrey Wilder."

The thing that cinched the career for which Mike had been born was a still-remembered social event of 1944 called the Cads Ball. In those days stars were really stars, groomed by their studios. They dressed up. They went out to dinner. They gave parties, and other stars came. A quartet of the town’s best-known bachelors—Cary Grant, James Stewart, Eddie Duchin, and the social figure John McLean, whose mother, Evalyn Walsh McLean, owned the Hope diamond—decided to give a ball to pay back all their hostesses. Mike Romanoff masterminded the whole thing. What he understood better than anyone else was how to give a party. He took over the Clover Club. Eddie Duchin provided the two bands. Hoagy Carmichael played the piano. The party went on until dawn. Dinner and breakfast were served, and— most important of all—every beautiful girl in town was invited. I recently asked my friends Mrs. Billy Wilder and Mrs. Fred DeCordova to share their reminiscences of that evening with me. They were then Audrey Young, a band singer, and Janet Thomas, a starlet, and all these years later they remember the night in detail.

“Jimmy Stewart brought Rita Hayworth,” said Janet DeCordova.

“Jane Greer, Myrna Dell, and I saw Annabella break up with Ty Power that night,” said Audrey Wilder.

“Lila Lee came in with Howard Hughes,” Janet DeCordova said, “and Lila and I were both wearing red, and Howard Hughes said you can’t both wear red dresses, and he called Howard Greer, the designer, and Howard opened up his shop and sent over a blue dress for Lila.”

“Oh, listen,” said Audrey Wider. “While we’re on the subject of Romanoff’s, I want to straighten something out. I did not hit Randolph Churchill in the face with a fish that night, the way the papers said I did. He said, ‘Oh, shut up, you ridiculous woman,’ and then said it again, so I just slapped him with my napkin across his face. He was impossible. He was so rude.”

As my conversations with them ended, each woman said, “I loved Mike.”

Everyone says that. Carol Marcus Saroyan Saroyan Matthau, one of the debutante triumvirate that included Gloria Vanderbilt and Oona O’Neill, told me over the phone in L.A., “Mike was the sweetest, nicest man who ever lived. Oona and I were out here alone when we were about 16 or 17. We wanted to go to Romanoff’s to see all the stars. We often went there for lunch. We never got a bill. Mike would say, ‘You’re two little babies. You can have anything you want here.’ He’d sit down with us and ask where we were going. When we told him, he’d sometimes say, ‘Oh, no, don’t go there,’ or, ‘You mustn’t see so-and-so.’ He really cared.”

"Michael went to work for Dick Zanuck," said Gloria Romanoff. His real job was to keep Sinatra in line."

Robert Wagner, the movie and television star who was married to the late Natalie Wood and whose friends all call him R.J., also remembers Mike with affection. “Mike was a true prince, far more so than some of the princes I’ve met,” he said. We were having lunch at Chez Mimi in Santa Monica. Like me, he enjoys talking about old times. He remembered some of the great nights at Romanoff’s. “Natalie had her 21st-birthday party there, and Sinatra gave it for her.... I was there the night Jayne Mansfield made up her nipples when she was sitting next to Sophia Loren at the Boy on a Dolphin premiere.... The studio wanted me to wear my Prince Valiant costume to the premiere party at Romanoff’s, but I only wore the wig, and someone from the studio took me over to meet Joan Crawford, who was sitting in a booth, and I knelt down to speak to her, and she said, ‘Get up!’ She didn’t like the way her neck looked in photographs when she was looking down.” Then he added, “God, I miss Mike. Every year he’d send me a present, like a silk scarf. ‘For you, my boy,’ he’d say.”

When Romanoff’s opened in 1939, it was located on North Rodeo Drive, in the building that several decades later would house the Daisy, Hollywood’s famous private discotheque. Mike sold $50 shares to such people as Harry Crocker of the San Francisco Crockers, the movie-star sisters Constance and Joan Bennett, and many of the studio heads. Jock Whitney, Alfred Vanderbilt, and Laurance Rockefeller put up the big money in $5,000 shares. On opening night, all the investors were invited, but Romanoff had overlooked one thing: there was no cash in the cash register. Mike told Cary Grant of his plight, and Grant, although notoriously tightfisted, had his butler bring boxes of cash from his house, and saved the night. From the beginning the restaurant was a success. Mike understood the importance of mixing groups. Even the Los Angeles establishment—the old families such as the Dohenys and Chandlers, who generally gave Hollywood people a wide berth— became regulars. The word spread. It was wartime, and traveling Washington dignitaries always dropped by. The only restaurant of consequence that rivaled Romanoff’s for the A-group was Chasen’s.

Beverly Hills was a village in those days, and Rodeo Drive bore no resemblance to the Rodeo Drive of today. Mike would stroll up and down it and check in with the shopkeepers. The actress Gail Patrick, who played Carole Lombard’s mean sister in the film classic My Man Godfrey, had a shop called Gail Patrick’s Enchanted Cottage, which sold rich-kid baby clothes. There was a wonderful, old-fashioned bookstore called Marion Hunters and—shortly after Mike moved to his second location— a South Seas hangout called the Luau, which was owned by Stephen Crane, the father of Cheryl Crane, who knifed Johnny Stompanato, the gangster lover of her mother, Lana Turner, to death. Everyone knew everyone else.

One day a young German named Kurt Niklas walked into the old Romanoff’s and asked for a job as a waiter. It was shortly after World War II, and men with German accents were not warmly regarded. He was tall and slender, with an attitude that could be interpreted as arrogant. The captain took an instant dislike to him and told him to get lost. From the sidelines, Mike, who had been watching the exchange, called the young man over. He had seen something in him. Niklas went on to work for him as a waiter, and soon became a favorite of customers such as Charlie Chaplin. Then Mike made him a captain. When the restaurant moved to a larger location, on South Rodeo Drive, Niklas went along and eventually became the maitre d’.

Soon after Romanoff’s closed for good on New Year’s Eve 1962, Niklas opened his own restaurant, the Bistro, in which I was an investor. It became the restaurant of choice for the smart set of Beverly Hills, including Mike Romanoff himself. Kurt then opened another place down the street, the Bistro Gardens, which is now the site of the new Spago. Recently, Kurt and I met up at the Bistro Garden on Ventura Boulevard in Studio City, in the San Fernando Valley, a beautiful restaurant that looks very much like the old Bistro. Kurt is now 72 years old and still has that attitude that could be interpreted as arrogant, but that’s just part of him. He told me that he had remarried his first wife, Mimi, and that she sent her love. Years ago, their kids and my kids went to Catholic Sunday school together at Good Shepherd Church in Beverly Hills. Kurt brought with him the manuscript of his unpublished autobiography. “Everything you want to know about Mike Romanoff is in this book,” he said, placing it on the table. He said he couldn’t get a publisher, because he wasn’t a celebrity like Mike. I read his book, enjoyed it, and learned a lot that I hadn’t known. He describes Mike the first day he saw him: “He was dapper in riding breeches, leather boots, a tailored tweed jacket, and a silk ascot. He had a brush haircut, jug ears, a military mustache, and a bulldog named Confucius.”

Kurt told me one anecdote that is in the book: “Elizabeth Taylor came in one night and dropped her sable coat on the floor, and then Mike Todd dropped his coat on the floor, and I wouldn’t pick the coats up. And Mr. Romanoff said, ‘Leave them there, Kurt.’” He spoke in an amazingly accurate imitation of Mike’s high-class voice.

If you were a swell in Hollywood in the late 50s, one of the swellest events to be invited to was Saturday-afternoon croquet at Sam Goldwyn’s. The Goldwyns lived in a beautiful white brick mansion with lovely grounds and a croquet court on a par with those at English castles. I went a few times just to watch, because I knew Sammy Goldwyn Jr. The ladies who came to look looked pretty, and all the players were gents. Herbert Bayard Swope Jr., a producer at Twentieth Century Fox, whose father, the editor of the New York World, had the best croquet court on Long Island, was a regular, as was the producer William Hawks, who sometimes brought his famous brother, Howard, the director. Louis Jourdan, the French film star who still lives in Beverly Hills, was always there. So was the movie star George Sanders, who was then married to Zsa Zsa Gabor. People like that. But the one you couldn’t take your eyes off was Prince Mike Romanoff.

Recently I phoned Sam Goldwyn Jr., who is no longer called Sammy. He lives in his parents’ old house. Even though we were talking on the telephone, I knew he was smiling when. I asked him about the bitter rivalry on the croquet court between his father and Mike Romanoff. Sam Goldwyn was a studio head and a very imposing figure, who used to scare me to death. “My father and Mike had these terrible fights, because my father would cheat,” said Sam. “They’d fight over the issue of starting over, or moving a ball, and they’d look to me for justice, and it was a lose-lose either way. My father was ready to disown me for disloyalty, and Mike would say, ‘Even though he’s your father, you have to be fair, Sammy.’ Sometimes their fights got so bad they were never going to speak to each other again, and then my mother and Gloria Romanoff had to step in and intercede so that they could all go in to dinner.”

I hadn’t seen Gloria Romanoff, Mike’s widow, for years. Sometime after Mike’s death, in 1971, Gloria moved away from Los Angeles, as did I. We lost touch. When I contacted her about this article, she said she would prefer to meet me in Beverly Hills, rather than in the town where she lives. On a Saturday morning in January of this year, I watched her walk into the lobby of the Beverly Hills Hotel. Nowadays, most of the women I know, and even some of the men, alter their features with plastic surgery after a certain age, and it takes a moment, sometimes longer, to adjust to the revised version. Not so with Gloria. She’s gone along with the natural process of time, and she looked great. Her hair is partially gray. “Classy” was the word that came to mind. She wore a dark-blue suit and a string of pearls. She said she had just driven by her old house on North Beverly Drive, not far from the hotel, where she and Mike—whom she always called Michael, and still does—lived for so long, next to her great friend Rosalind Russell. She could barely recognize the house, subsequent owners had changed it so much. It was a wonderful house, Spanish in style, at least back then. I reminded her of a long-ago dinner dance she and Mike gave in that house for the visiting Alfred Vanderbilt, who had a horse running at Santa Anita. It was when Cary Grant was courting Dyan Cannon, and they never stopped dancing the whole night, so in love they seemed to be, but the marriage that followed didn’t last long.

Gloria Lister came to Hollywood with her family from Rhode Island in 1943. She went to work for Paul Frankl, an avant-garde furniture designer who had a studio on Rodeo Drive. One day Mike came into the studio with Fanny Brice, the great comedienne, who dabbled on the side as a decorator for her friends. Romanoff had recently bought his first house, and Fanny was doing it up for him. After they left, Frankl said to Gloria, “He was certainly charmed by you.” Gloria told me, “I thought he was different and amusing and interesting. He was never a man who had an appetite for acquiring money. He wanted an interesting life.”

"Despite a 34-year age difference, they began to go out together socially. “I was never a kid kid,” said Gloria. “I always preferred the company of older people.” Mike’s close friends at the time were Robert Benchley, the humorist, the movie mogul Darryl Zanuck and his wife, Virginia, and Humphrey Bogart, who was then married to the famously hot-tempered Mayo Methot. Their public fights were legendary. “Mayo was a reasonably contained woman when she wasn’t drinking,” said Gloria. She left her job with Frankl and went to work for Mike at his restaurant. “He needed someone to organize his office.” Romanoff was very much the front-of-thehouse man, the greeter, the charmer. Gloria managed the rest.

Romance soon entered the picture. “I was quite serious about Michael,” she told me. “This was the man I wanted to marry.” But Mike, who had never been married and liked the ladies, was not the marrying kind. Gloria decided to move on. She decamped to Palm Beach as secretary and companion to a famous socialite of the period named Dolly O’Brien, a Waterbury, Connecticut, beauty who had married well several times and was then in the midst of a highly publicized affair with Clark Gable.

Mike missed her. As luck would have it, Winthrop Rockefeller, the second-youngest son of John D. Rockefeller Jr., was marrying a showgirl-singer named Barbara Sears, known as Bobo—whom Mike had known in Hollywood—at the Palm Beach home of the socially distinguished Winston and C. Z. Guest. Mike went from Los Angeles for the wedding, and Dolly O’Brien gave him a dinner party with a guest list that included all the great Palm Beach names, as well as the Duke and Duchess of Windsor, who were on their annual winter sojourn at the resort. Several decades earlier, when the Duke was the Prince of Wales and Mike was still passing himself off as a nephew of Czar Nicholas’s and the son of the man who had killed Rasputin, he had often referred to the Duke in interviews as Cousin David. Like many who had figured in Mike’s stories, the Duke was charmed by him. Gloria remembers that Laurance and Nelson Rockefeller, the wary brothers of the groom, kept quizzing Mike right up until the wedding ceremony about the social acceptability of Bobo Sears. “Everyone knew Michael from his speakeasy days in New York,” said Gloria. After the wedding, Mike lingered for a few days. Finally he said, “I’d like us to be married.”

Gloria finished up the season with Dolly O’Brien and returned to the West Coast. They chartered a plane and were married in Las Vegas on the Fourth of July 1948, after attending a party that day in Los Angeles. Gloria was 24. Mike was 58. “I’m never going to be rich,” he told his bride, “but we’ll have an interesting life—an adventure.” They moved into the house on Chevy Chase Drive in Beverly Hills that Fanny Brice had decorated for him. “He was heaven to live with,” said Gloria. “He was terrified of getting married, but he loved it.”

Gloria spoke about Mike’s sense of fellowship. After the gentleman Film producer Walter Wanger Fired a gun pointed at the testicles of the Hollywood agent Jennings Lang, whom he suspected of having an affair with his movie-star wife, Joan Bennett, and was incarcerated in the Beverly Hills jail, Mike, who knew a thing or two about jails and gentlemen in jeopardy, had a waiter from Romanoff’s take him over dinner on a tray. Mike himself later took him silk pajamas, and a pipe and tobacco.

“After the restaurant closed,” Gloria told me, “I went on working for a while. I ran the Lily Pulitzer Shop next to the Bistro. Michael went over to Fox to work for Dick Zanuck, who was head of the studio after his father. His real job was to keep Sinatra in line. Frank had a deal with Fox for a couple of pictures. Did I tell you that Michael was Dick Zanuck’s godfather?”

It is said, and this story did not come from Gloria, that at the very end, in the hospital, Mike asked everyone to leave the room—the doctors, the nurses, whomever. Then he looked at Gloria and said, “Not you, my darling,” and he died.

The day after I saw Gloria I had lunch with Nancy Reagan at the Bel-Air Hotel. “How was Gloria Romanoff?” she asked. I told her. “I haven’t seen her in years,” said Nancy, thinking back. That night I had dinner with Lew and Edie Wasserman at Dan Tana’s. “How was Gloria Romanoff?” asked Edie. I told her. “I haven’t seen her in years,” she said. Like her late husband, Gloria Romanoff is remembered with great affection.

I recently called Prince Alexander Romanoff in New York. He is a genuine Romanoff, of the family, in line in the highly unlikely event of a restoration, who did not attend last year’s burial of Nicholas and Alexandra in St. Petersburg only because he was ill. “Oh, yes, I met him twice in my youth. He was full of invention,” said the prince. “I was taken to the restaurant, and all the stars were there. I thought he was exceedingly ugly. We just said a few words to each other. My hostess said about me to him, Alexander is a real Romanoff’ He replied, ‘But I’m the only Mike Romanoff.’”

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now