Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowEditor's Letter

Against All Odds

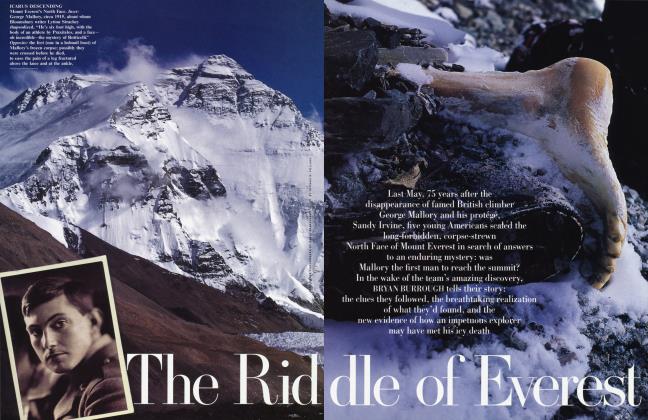

The upper reaches of Mount Everest may be littered with the bodies of its victims, but its challenge to climbers remains irresistible. The noted British mountaineer George Mallory is believed to have been the man who, when asked why he wanted to climb Everest, gave the glib answer "Because it is there."

Mallory had already tried to conquer Everest twice when he and his protege, Sandy Irvine, disappeared, during a third attempt, on June 8, 1924. Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay reached the top in 1953, but in mountaineering circles the question still remained: Had Mallory been the first to scale the world's highest peak?

Seventy-five years after Mallory and Irvine vanished on the North Face of Everest, five Americans led by a veteran guide named Eric Simonson set out to retrace the Englishmen's climb. The reason they might have given for their expedition was "Because Mallory is there." While increasing numbers of climbers had been scaling the mountain's southern, Nepalese side (including those who perished in the 1996 blizzard so memorably described in Jon Krakauer's bestselling book Into Thin Air), the North Face had been closed to foreigners by the Chinese government for three decades. But a corpse, thought to be that of Sandy Irvine, had been spotted by a Chinese climber in 1975. If the team could find that body, perhaps they could answer the riddle of Everest. On page 284, Vanity Fair special correspondent Bryan Burrough skillfully weaves together two stories, alternating the heartbreaking tale of the handsome, impetuous Mallory with the American team's gripping account of its seemingly quixotic search and stunning discovery. What Simonson and his colleagues found may at some point tell us once and for all what happened to Mallory and Irvine, who lost their lives in pursuit of a dream that mountaineers the world over continue to hold.

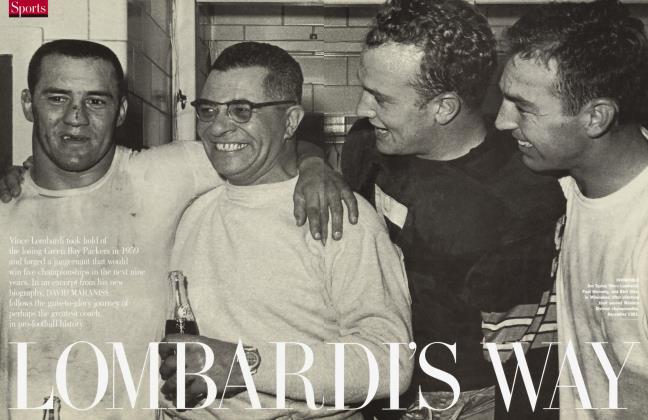

In 1959, 45-year-old Vince Lombardi set out on his own journey. Leaving his job as an assistant coach of the New York Giants, he got into his battered Chevy and drove halfway across the country to the snow-swept plains of Wisconsin. His goal: to take the struggling Green Bay Packers, who'd become the joke of American football, and turn them into a winning team. As Pulitzer Prize-winning writer David Maraniss recounts in his forthcoming biography, When Pride Mattered: A Life of Vince Lombardi, excerpted on page 206, Green Bay's new coach succeeded beyond all imagination. Relentlessly applying his uncompromising standards, his Jesuit-inspired coaching methods, and the bizarre philosophy of worthwhile pain learned from his parents, he drove the Packers to a decade of almost unprecedented glory, with five championships in nine years. But the ultimate expression of Lombardi's achievement may have been the now legendary "Ice Bowl" game, on New Year's Eve 1967, in which the aging Packers faced apparently insurmountable odds (not to mention 16-degrees-below-zero weather) against Tom Landry's increasingly dominant Dallas Cowboys. CBS's Ray Scott said the Packers' final drive "was the greatest triumph of will over adversity I've ever seen." On the gridiron, as on the mountain, it's those who pit their own will and endurance against epic adversity who make the dreams come true.

GRAYDON CARTER

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now