Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowWANTING TO EXHALE

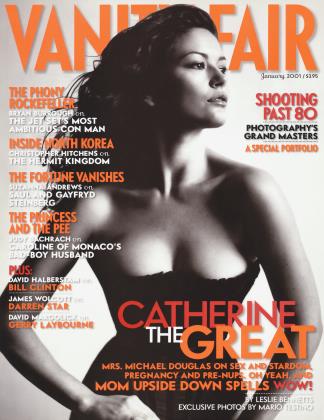

When legendary TV executive Geraldine Laybourne started Oxygen, a new cable and on-line network for women, it seemed she was bringing every asset to the table: the creative halo she’d earned at Nickelodeon, a partnership with Oprah Winfrey, and $300 million from backers. But, DAVID MARGOLICK reports, critics have panned such giggly Oxygen fare as Pajama Party, and cable operators may turn Laybourne’s programming revolution into “Can’t-See TV"

Geraldine Laybourne is surely the most successful ex-schoolteacher in the world. She turned Nickelodeon into one of the most valuable properties in television. Disney chairman Michael Eisner personally lobbied her to join his company. Twice, in 1998 and 1999, Fortune crowned her the 20th-most-powerful woman in American business. Solely on her reputation and the sheer force of her personality, she defied the naysayers and, two years ago, raised $300 million to start a new women’s cable television and on-line network, in part by recruiting two of television’s other most powerful women, Oprah Winfrey and television producer Marcy Carsey, to join her. And earlier this year, in February, she actually got that network—which she christened Oxygen—on the air.

But, for all Gerry Laybourne has accomplished in her 53 years, there remains one thing that even she still can’t do. She can’t get Oxygen in her own home, an apartment on Central Park West in Manhattan. Nor can most of her 700 employees, who live in and around New York City. Nor can most of America’s media elite. Nor, for that matter, can 9 of 10 Americans with television sets, and 6 of the 7 who have cable. Among those who still cannot watch Oxygen are many people who believe Laybourne is a gutsy visionary who has dedicated her entire career to making television better. And many others who think she’s a self-righteous self-promoter who has spent years cultivating a fawning press and then believing everything it has written about her. And some who predict that Oxygen will one day become a powerhouse. And still many others who consider it doomed, a victim of colossal hubris and chutzpah.

Suppose they put on a new network and nobody came? Or watched? More than two years after it was first bruited about as the antidote to traditional women’s television, more than a year after its much-heralded Web sites first went on-line, and nearly a year after its first telecast, Oxygen remains the stealth network, not only off most television screens but off most radar screens as well. Have you ever seen it? Have any of your friends? Though they claim it is now in roughly 12 million homes, these are largely in the “fly-over” states—those barren hills and desolate plains in Saul Steinberg’s famously distorted New Yorker map of the United States, all of those states that went G.O.P. red on the electoral-college map. Oxygen’s predicament is neatly encapsulated in the name of the venerable old game show it has resurrected: I’ve Got a Secret. To listen to industry insiders, its financial predicament could be called Beat the Clock. And whether it can surmount the enormous financial and programmatic hurdles before it is The $64,000 Question. Or, rather, the $450 million one.

Oxygen may be floating all around us, but getting Laybourne’s version of it on the air at a time when cable systems are saturated and shelf space scarce is, by any measure, astonishing. So are its offices, on four floors of a converted Nabisco factory in the Chelsea section of Manhattan. But keeping it all going—devising must-see television in a marketplace that still hasn’t shown that it wants it, then finding enough advertisers and investors to bankroll it—may prove the neatest trick of all. Laybourne, who built Nickelodeon, the cable network for children, in the 1980s, when expectations were low and no one was watching, is now in the center of the big top, and on the highest high-wire act of her career. Always, she has assumed that no deathdefying stunt was beyond her. But to many in the tent, friends and foes alike, she’s wobbling.

“My whole entire career, people have told me, ‘It’s impossible,”’ she says. “They told me Nickelodeon was impossible, they told me building Nick Studios was impossible, they told me building Nick Films was impossible—they told me everything was impossible. And you know what? I never paid attention to that. I paid attention to the drive that I have to do something great and to do something different and to make a difference in the world.” How, I ask her, has she always managed to defy the odds? “I’m just an ornery cuss,” she replies.

She sits, wearing her trademark black leather tailored jacket and green wire-rimmed glasses, in her modest office, in a space where Oreos and Lorna Doones were once made. To her, life in a renovated cookie plant is apt, and not because junk food is forever popping up in Oxygen, whether in advertisements or conversations or on the sets, where glazed doughnuts seem as common as bouquets, ever tempting diet-crazed hosts and guests. “It says to me that we’re builders and makers and that we’re going to grow stuff and we’re out in the open and that what we do is for everybody to share,” she says. “It’s energizing to be in this space. It’s a bakery. This is not an office building where we’re shuffling papers. This is a factory.”

Two years ago she spotted what she considered a hole in television programming every bit as gaping as the one she’d seen 20 years ago for children. To her, the women’s offerings already out there—a smorgasbord of soap operas, sob stories, victimization, rapists, and diseases of the moment—catered to outdated, condescending notions of feminine wants and needs. So Laybourne, whose personal Decalogue—she calls it Mother’s Little Management Manifesto—includes “Think Big” (her Sixth Commandment) and “Take Risks” (her Seventh), set out to create something different. It would serve younger, hipper, busier, more assertive, and more confident women—“women who are leaning into their lives, who are independent and eager to take charge.” It would feature large chunks of original programming, not the tired reruns with which other new cable ventures had gotten their starts. And, employing the much-hyped concept of “convergence,” which meant availing itself of the new, interactive technology of the Internet, it would listen to its viewers and “co-create” with them. She called her new venture Oxygen, a name that came to her at her ski house in Telluride, Colorado, where the bed is on wheels so she can sleep on the balcony, under the stars. She awakened one morning gasping for oxygen in the thin alpine air and realized that, in our frenetic society, every woman needed to take a deep breath.

ABC s then president, Robert Iger, came to write Laybourne off as a "loon” and a "pain in the ass’ according to two other executives.

Legendarily persuasive and well connected, Laybourne sold her idea to the principals of CarseyWerner-Mandabach, makers of mega-hits such as The Cosby Show, Roseanne, and 3rd Rock from the Sun, who would put together Oxygen’s programming. Then she and her new partners— Carsey, 56, Tom Werner, 50, and Caryn Mandabach, 50—flew to Chicago and sold the idea to Oprah Winfrey. “I think some angels showed up today,” Oprah wrote that night in her journal. Then Laybourne sold it to such investors as Microsoft co-founder and billionaire Paul Allen and LVMH chairman Bernard Arnault, who together ponied up half of the $450 million she figured she’d need to run Oxygen for its first five years. Then she sold it to some cable operators. And then to the media, which bought it Big Time. Forbes put the triumvirate of Laybourne, Winfrey, and Carsey—a female DreamWorkson its cover. Before beaming a single image, Oxygen was said to be worth more than $ 1 billion.

Then came the reality. With few or no analog slots available and digital television perpetually off somewhere in the future, crucial cable operators such as Time Warner (which has a stranglehold in New York City), Cablevision, and Comcast declined to pick up Oxygen. Their resistance stiffened because rather than paying for “carriage,” as most new cable networks do, Laybourne was actually charging operators 19 cents a subscriber. Moreover, the operators felt that women were already well served. For one thing, they had Lifetime; while Laybourne may have considered it “mindless” and “a drug,” as she told associates, it was wildly popular—in almost 78 million homes—and had improved since Oxygen began yapping at its heels. Women also had cable channels for romance and food and gardening, as well as the traditional broadcast networks, which have never been exactly indifferent to women viewers. In this instance, Laybourne’s First and Fifth Commandments—“Know the Audience” and “Challenge Conventional Wisdom”—may actually conflict; women may already be getting what they want. “If it ain’t broke, fix it an> way” is one of Layboume’s favorite aphorisms, but it could also be her epitaph.

Had Oxygen’s first crop of programs created buzz or demand, all doubts might have disappeared. But carving out a programming niche, like winning a slot on the cable box, is rough going; Oxygen finds itself faulted simultaneously for being too , girlie-giggly and too angrily male-bashing, too highbrow (television for people who don’t watch television), too lowbrow (unworthy of its revolutionary, uplifting mission), and too middlebrow (too much like everything else already out there).

A n animation series, A X'-Chromosome, is / hip, edgy, stimula/ ^k ting, original. Can/-^k dice Bergen’s talk / ^k show, which Oxy_Z_ gen may soon share with PBS, is charming and entertaining, but hardly trailblazing. (Question to Melissa Etheridge: “Of all the sperm in the world, why David Crosby’s?”) Trackers, a concert/talk show/ confession-fest for teenage girls just home from school, is fun but not always elevating; staffers nearly revolted early on when the misogynist rapper Snoop Dogg, surrounded by pot smoke and an entourage of scantily attired women, appeared on the show. (Such “candy” was needed to build an audience, they were told.) The day I stopped by, panelists named Shannon, Adrianne, and Tara competed to see who could make herself look the most “cheap and tarty” in 20 seconds, and—in an odd nod to convergence—pondered the following question: “Would a majority of your cyberfriends rather have one million zits or one million moles?”

As She Sees It features impressive documentaries primarily by or about women. But Pajama Party can border on moronic. The episode I saw, part of the care package of cassettes Oxygen sends to anyone wanting a whiff of its programming, featured a segment called “Surgery Showcase,” in which, as they sipped frothy, fruity drinks, hosts Katie Puckrik and Lisa Kushell compared the scars left behind from their spinal operation and nose job, respectively. Both inside and outside Oxygen, people fault Laybourne for yielding too much authority over programming to Carsey-Wemer-Mandabach, and particularly to Mandabach, who has been the most involved of its three California principals. “Would Gerry Laybourne want to watch a pajama party?” one woman in television asked incredulously. They say that Oxygen reflects the cultural chasm between the coasts, with Mandabach’s Hollywood vision— “a little bit more glitz, glamour, and yoga and baby-massagetype things,” as one Oxygen alumna put it—prevailing over more East Coast, socially conscious, feminist fare. Laybourne insists that all partners are on the same page.

Carsey said even her grown daughter is reserving judgment on Oxygen; she still hasn’t seen enough of it. The press has not been so reticent. In The New York Times Magazine, Francine Prose lumped Oxygen in with the very programming Laybourne had repudiated: “brainless, narcotizing amusement.” In Salon, Joyce Millman called Oxygen “a depressing jumble of retro stereotypes and empty ‘u go, girl!’ solidarity” (and added that it was “absolutely obsessed with body image”). Jesse Oxfeld of Brill’s Content chastised most of what he saw on Oxygen, but only after reconstructing his Odysseus-style voyage in search of a television set, any television set, on which the channel was available.

if she’s a total bust? So what? She tried. I think she’s going to be wildly successful, but even if she’s not, she tried with quality and honor and passion.’

“Branding” is everything these days, and the new network’s catchy name lent a pleasing leitmotif to its schedule. There are, for instance, Inhale (its morning yoga program), Pure Oxygen (its midday talk show), and Exhale (Bergen’s evening talk show). But the neat name cuts both ways. “Gasping for Oxygen,” the New York Post declared above a story about Laybourne’s efforts to penetrate New rk. After the network closed two of its Web sites and placed Trackers and Pure Oxygen on hiatus for the summer, The Wall Street Journal said that Oxygen was “coming up for air.” And when Fortune dropped Laybourne from its list of the 50 most powerful women, in October, it said that Oxygen was “gasping for viewers.” It seems only a matter of time before someone asks if Oxygen is suffocating. One former colleague of Laybourne’s has gleefully taken to calling Oxygen “Carbon Dioxide.”

The Schadenfreude might be surprising, given that Laybourne has received years of adulatory press, often written by younger women who have portrayed her as both shrewd and Earth Motherly. Detractors and admirers alike say that she is a kind of cult figure, worshiped by female acolytes. But at both Nickelodeon and Disney, Laybourne left a considerable residue of resentment. People at both places speculate that her outsize ego led her to think she had spotted a hole in television that everyone else was too blind or too primitive or too sexist or too timid to see. These people believe that Laybourne’s clairvoyance is a bit of a myth— “She has yet to prove herself with an audience half of whom don’t believe in Santa Claus,” one sneered—and that with Oxygen she may finally get her comeuppance.

But Laybourne’s fans think she will pull it all off. “Starting a new cable network is a tough game no matter who’s doing it, but I would never count Gerry out,” said Tom Freston of MTV, Laybourne’s boss during her days at Nickelodeon. Leo Hindery, whose cable company, Tele-Communications, Inc., was the first to sign up Oxygen, and who hawked Oxygen tirelessly to other cable operators, calls Laybourne “messianic” and says she “walks on water.” Bob Pittman, who promoted Laybourne to the top job at Nickelodeon, agrees. “Gerry has whipped together a great team,” said Pittman, who as president of America Online received a small stake in Oxygen in exchange for three women’s Web sites. “There’s a name out there, the product is up and running, they’ve got a buzz going.” He predicts that she’ll find additional funding—“Someone with Gerry’s reputation and skills set will always get money”—and says Oxygen’s 12 million subscribers are nothing to scoff at. “After a year on MTV [where Pittman was president] we had 500,000, so it sounds pretty good to me.”

At least theoretically, Pittman could get Oxygen onto New rk’s television sets virtually overnight when the AOL-Time Warner merger goes through. But when asked about giving Laybourne a coveted slot on Time Warner Cable, Pittman suddenly grows more cagey. “I don’t run the cable company,” he says. Those who do— Joe Collins and Fred Dresler—aren’t talking. But one Time Warner executive who did talk says that Oxygen has yet to earn its spurs. “We like Gerry, but at the end of the day, the law of business has not been suspended,” he says. “You have to have a product and you have to price it right.” In this respect, the Time Warner brass has been entirely consistent; a prominent cable executive recalls watching Caryn Mandabach approach Time Warner chairman Gerald Levin at a cable convention not long ago. “Let me talk to the most important person in the cable business and our future,” she cooed. “Not me,” he replied. “Talk to my people.”

Manhattan’s Chelsea Market is the only place in the world where the Oxygen gets thicker as one climbs higher. Walk through the ground floor, with its smells of fresh flowers and cookies and soups and breads, take the industrial-strength elevator to the seventh floor, and you trade a world starved for Oxygen for one suffused with it. On one monitor, Oprah’s best friend, Gayle King, and Ellen DeGeneres’s mother were discussing gay children. On another, the topic was children’s cold medicines. On a third, some new Oxygen promotions were flashing by.

“Think like a mom,” one declared. “Candy striper. Starlet. Friend. Think like a rocket scientist. Teacher. Single mom. Superstar_Think like a goddess. Matron. Den mother. Beauty queen. Think like a lover. Bunny. Soccer mom. Hostess with the mostest. Oxygen. Think like yourself.” Another stated, “Oxygen: Enjoyed by bad girls everywhere.” Cut to a woman, bundled up for winter. “To snow tire or not to snow tire, that’s a question,” she said brightly. Cut to three voices. “It’s all chicks?” one asked. “Yeah, nothing but,” said another. “Play like a girl with Oxygen Sports,” said the third. Cut to a woman, alone, in a wedding dress. “We were supposed to get married, but he blew me off,” she said. Cut to a mother meeting her newborn baby. “Happy Labor Day from Oxygen.”

CONTINUED ON PAGE 159

CONTINUED FROM PAGE 105

The clips were a reminder that Oxygen’s target audience is younger and sassier than Lifetime’s. But demographics matter less to Laybourne than what she calls “psychographics.” Famously addicted to socialscience research and focus groups, she says women fall into five distinct categories. There are “the disaffected,” for whom television is a narcotic, like tobacco—“They will never watch Oxygen,” she says. There are “the contented,” some of whom might occasionally tune in. Oxygen is aiming for the rest: “the achievers,” “the changers,” and “the adventurers.” “Women today don’t feel like they’re victims, they don’t feel ‘Woe is me,’ ” she explains. And they are sophisticated: No longer can women’s programming be “just about 59 ways to thinner thighs.”

So far, Laybourne feels her vision has been fulfilled. “We’ve hit all of our targets, in terms of revenues, in terms of subscribers, in terms of page views,” Laybourne claims. Her script calls for Oxygen to be in 50 million homes by 2004; by the end of 2002, she says, it will be two-thirds there. (That’s crucial because, while Oxygen has struck special deals with Johnson & Johnson, Hewlett-Packard, and Procter & Gamble, advertisers generally do not pay much attention before a network can claim 20 to 30 million subscribers.) Oxygen executives say that the network is available in some parts of Los Angeles, and will soon be available in more. As for programming, “we’ve created 15 completely different new series, right out of the box. That’s unheard of. There is no new network with that much original content that looks as good as Oxygen. Nowhere. Not in any country of the world. It’s so great. The only thing it isn’t is the Second Coming, and we never thought that.” So eager was she to push convergence, she admits, that Oxygen passed on more expensive, labor-intensive programs—dramas and comedies. But CarseyWemer-Mandabach will soon rectify that with a multigenerational sitcom and other projects.

Laybourne ridicules the notion that had Oxygen not been so hyped at the outset it would not be so scrutinized now. “And that would really have been possible with Oprah Winfrey, Marcy Carsey, and me,” she says sarcastically. “That’s a great piece of advice. That’s brilliant. I wish I thought of that myself.” Nor, she says, was getting on in New York right away or having a smash hit at the start ever realistic. “People say, ‘Well, why didn’t you have a hit out of the box?’ I don’t know, because that was on our business plan: Have a hit, right out of the box,” she declares. Her disdain for such fatuous thinking is obvious, but she is taking no chances. “If you’re going to quote me, you better put that there was a smirk on my face,” she says. No one remembers, she points out, that it took Five years for Nickelodeon to make a hit out of Rugrats.

Oprah has seemed scarce around Oxygen, apart from a 12-part series in which she and Gayle King learned how to surf the Internet; her promised talk show, Oprah & , has yet to happen. Around the office, staffers have seldom seen her, and were told to steer clear of her when they did. Nor has she done much on her syndicated show or in her wildly popular new magazine to push Oxygen, stoking rumors that she is unhappy with how it has evolved and is distancing herself from it.

Carsey concedes that she and her partners have trod lightly with Oprah, fearing she is stretched too thin. But Winfrey, she says, recently asked to become more involved; during a visit to New York in October, she gave a pep talk to the staff at Pure Oxygen, pledged to call the control room periodically to kibitz on-air, and offered to film an upcoming trip to Africa for Oxygen. Winfrey’s level of participation evidently satisfies Laybourne. “This isn’t called Oprah," she says. But it’s clear that even she proceeds gingerly with Winfrey; she could not deliver her for an interview, forcing me to settle for a pallid written statement instead. (In it, Winfrey reiterated her faith in Oxygen and pledged to give it her continued “creative energies.”) The folks at Oxygen made me feel that both I and they were lucky to get even that.

Oxygen is a private company—in today’s bear market, going public is no longer an option—and Laybourne will not say how much of her original $300 million stake she’s already burned through, nor what her profits and losses have been. She is now looking for an additional $ 150 million, offering stock warrants and chunks of the company—though not, she says, all or even half of it, as The Wall Street Journal reported in October—in return. It’s not a fire sale, she insists, but something that was planned all along. With dollars so much scarcer now, her task is not easy, particularly since many consider Oxygen’s revised, reduced valuation—$700 to $900 million—still way too high. Paul Allen, who has already put up $100 million, is said to be ready with more. Viacom chief Mel Karmazin was recently seen around Oxygen, but he can’t invest in it without winning over Viacom chairman Sumner Redstone, and Redstone, who owns Nickelodeon, says he’s not interested.

Once, Laybourne predicted that the cable and Web sides of Oxygen would be equally valuable; given the collapse of Internet stocks, the ratio is probably more like 15 or 20 to 1. But her insistence, contrary to the advice of her investment bankers, that Oxygen be a joint cable and on-line property has been vindicated. “If we were just a dot-com company, you would be writing our obituary,” she says.

Does Laybourne think people are waiting for her to fail? “Oh, I hope not,” she replies wearily. “Not with the goodwill I have towards them. I hope not, for the state of manand womankind today. I’ve been so incredibly generous in my life to make opportunities for people.” But, for Gerry Laybourne, it’s always been “us” against “them”; it was Nickelodeon against Disney, and kids against their parents. I feel adversarial vibes from across the table; I am “them,” at least whenever my questions appear too pointed. But there is one question she actually wants me to pose. “You didn’t ask me if I was having fun,” she observes. She says she is.

Laybourne grew up in Martinsville, New Jersey. Her father, a stockbroker named Paterson Bond, gave his middle daughter his business savvy; from her mother, Gwen, who wrote radio soap operas and turned off the TV mid-program to make her children come up with their own endings, Laybourne got her dramatic flair. Shortly after graduating from Vassar in 1969, she married a free-spirited filmmaker named Kit Laybourne, now Oxygen’s head of Animation and Special Projects; two children quickly followed. One of them, 29-year-old Emmy, is appearing on the NBC sitcom DAG; the other, 26-year-old Sam, teaches in the New York City public schools.

Laybourne got a graduate degree in elementary education at the University of Pennsylvania, and taught prep school for a time. She also collaborated with her husband on children’s-television projects. It was through her filmmaking that Laybourne joined the new, struggling Nickelodeon in 1979. By 1984—when Nickelodeon had become part of MTV Networks—she’d taken over the place. She dressed up cheap old shows and, once the money started flowing, began creating her own, replacing eat-your-spinach fare with stuff kids loved: offbeat, irreverent, sometimes gross. Aided by public-relations guru Kenneth Lerer, Laybourne became one of Nickelodeon’s prime public assets; wholesome and soft-spoken, the antithesis of the fast-talking, ball-busting female executive, she was everyone’s favorite schoolteacher.

But not everyone at Nickelodeon shared in the glory. Though Laybourne was famously generous with praise inside the building, many felt she was stingy with it outside. Laybourne, too, grew unhappy. She resented MTV chief Freston, wanting to report only to Redstone after Viacom bought MTV Networks in 1986. She disliked Viacom’s then president, Frank Biondi, who she felt thwarted her work. That arch-rival Disney, whose programs she had long ridiculed, started courting her did not come as a surprise; a call to her from Michael Ovitz, then Disney’s number two, was mistakenly put on the speakerphone during a Nickelodeon meeting. Eisner and Robert Iger, then head of Disney-owned Capital Cities/ABC, also wooed her, and around Christmas 1995 they won her hand, in a deal said to be worth some $3 million a year. “I’m not a psychiatrist, but you might say it was a way to express her disdain for the way she was treated: ‘I’m not only leaving but going to the arch-enemy, so fuck you too,’” one eyewitness recalls. The executives she left behind seem to relish telling you that Nickelodeon has nearly tripled in size since she departed.

With Disney having anointed her, Laybourne was, in the words of the Los Angeles Times, “unquestionably the most powerful woman in television.” But it was probably predictable that she could never have traded the warm, familiar bath of Nickelodeon for the more treacherous waters of Disney without running aground. After a short love-in, the Disney brass tired of hearing her endlessly tout her successes at Nickelodeon and drop Eisner’s name with a loud thud at every opportunity. On the Disney plane, one former Disney executive recalled, others usually held back until Eisner chose his seatmate; Laybourne swooped right in. When Eisner invited her along on a bicycle trip through Mississippi, everyone soon knew about it. Peers considered Laybourne high-maintenance. They felt she overresearched everything instead of going with her gut. Some thought her excessively concerned with her image as a reformer and a player; it didn’t help when a fan told The New York Times in 1997 that “the name Gerry Laybourne is better than Disney, because Gerry Laybourne is current.” Fairly or otherwise, when stories popped up touting her chances in Disney’s perpetual wars of succession, fellow executives thought they saw her fingerprints, or those of her surrogates.

The disillusionment soon became mutual. Ostensibly in charge of all Disney cable operations, she was irked that ESPN was outside her jurisdiction. Shortly after she arrived, Iger scotched a proposed 24-hour news operation that would also have been in her bailiwick. That Lifetime had a man, Douglas McCormick, at its helm had long rankled her, but because Disney and Hearst owned it jointly, her efforts to have him fired were frustrated. Her pet project, an ambitious educational network called ABZ, got nowhere, largely because it promised huge losses for many years to come. Mostly, the can-do, quixotic Laybourne was out of place in cautious, bureaucratized Disney—and she let everyone know it. “She wore her frustration on her sleeve,” another executive remembers, even “with the guy who delivered the mail.” Iger, who had once said that Laybourne was “great to have around,” came to write her off as a “loon” and a “pain in the ass,” according to two executives who worked with him. (Iger declined comment.)

In May 1998, scarcely two and a half years into her five-year deal, Laybourne left. With an eye on damage control, Disney gave her some money—“well under $10 million,” according to one who knew—and called it an investment in Oxygen. Laybourne says her Disney years “were really fantastic for me in a lot of ways,” and points proudly to her successes: inspiring original programming at Lifetime; tripling the number of subscribers to the Disney Channel; fixing ABC’s Saturdaymorning lineup of children’s shows. As for ABZ, she said that it was “probably ahead of its time and too radical a concept.” And at Disney, which was still assimilating ABC and tom over questions of Eisner’s health and succession, says Laybourne, “There wasn’t much room for bravery.”

“There are people who clearly didn’t like the fact that I was brought in at the level I was brought in and that there was so much hoopla about it,” she adds. “I know there were people who didn’t want me there.” And, she says, “there was plenty of jealousy. If my goal was to work my way up the ladder at Disney, I would have done a million things differently. I didn’t go to Disney to climb a career ladder, but to create new stuff.”

Free at last, free at last, Laybourne launched Oxygen. Determined not to enmesh herself with another large corporation, she declined an offer to join forces with Time Warner’s proposed—and subsequently aborted— women’s channel. She began hiring hundreds of people in mid-1999; for the young, the hip, the idealistic, Oxygen became the place to be. An “Oxygen Tank”—really an Airstream trailer—traveled around the country evangelizing. “You felt that the world was so behind Oxygen that it was exhilarating,” says Sarah Bartlett, a former student of Laybourne’s who was a reporter for The New York Times and an assistant managing editor at Business Week before signing on to run Oxygen.com (a post she has since left). Sleep-deprived staffers cheered when Oxygen ran a $2 million ad during Super Bowl 2000 (a gesture seen as profligate, pointless, and vain by outsiders) and cheered again during the gala launch at Chelsea Market three days later, when Laybourne and Winfrey ticked off the seconds until Oxygen went on the air. The date was February 2— 02/02 to chemistry buffs.

Always, there were skeptics. “I’m with you, Gerry, but I have my doubts,” television newsman Ted Koppel wrote in a journal entry at the time, now included in his book, Off Camera: Private Thoughts Made Public. The television critics were unforgiving last January when Winfrey and Bergen, due to a scheduling snafu, stood them up at the Television Critics Association convention. And, throughout, convergence proved premature on the outside—computers and televisions remained different machines, often on at different times and in different rooms—and problematic inside.

Internet start-ups are always difficult, but normally they are in the hands of qualified techies. However, workers on Oxygen’s Web sites felt like stepchildren, paid less and forced to work on far tighter budgets than their television counterparts. Because they had come from print or television, many on the Internet side didn’t know the technology. And Oxygen’s technology was primitive. E-mail didn't work. When a hacker put some pornography on one Web page, it took forever to fix; when viruses disabled the system, it took too long to get things back up. Morale plummeted in the Internet division; by this past summer, the going-away parties were communal, and one couldn’t walk by a printer without seeing a resume emerging.

Nothing exemplified the perils of convergence more vividly, and sometimes comically, than the teen show Trackers. Its Web site, like several of Oxygen’s sites at the time, was “flat”—that is, with only limited use of animation, audio, and interactivity. “And we were supposed to be a converged company,” one Web worker lamented. Convergence became largely cosmetic: the Internet types were told to work alongside the cable people, with the prettiest women (Mandabach’s daughter among them) placed strategically within camera range. Web producers were thereby forced to do their ruminative, highly complicated work in the midst of live bands, screaming teenagers, and a game show, and in subarctic conditions, too (the heat wasn’t working during the seemingly perpetual construction)— all for a product that cyber-sophisticated teens knew was inferior. “Teenagers spend tons of time on TV and the computer; it was such an obvious place to throw money and experiment,” said one of the many employees who fled shortly after the launch. “It’s totally tragic that it didn’t work out.”

Laybourne takes me down to the third floor, where Oxygen is at its most daring. She and her husband introduce me to Michael Rosenblum, a veteran documentary producer who runs a “digital boot camp” for Oxygen staffers, teaching them how to handle the ingenious compact digital video cameras that are revolutionizing filmed reportage. And to Julina Tatlock, who has “The Ruth Truth,” a fabulously clever interactive cartoon created by Sheila Head and directed by Tatlock, on her screen. In another room, Laybourne points to a small, redheaded woman huddled over a computer. “That’s Breakup Girl,” she says proudly, referring to Lynn Harris, creator of breakupgirl.com, one of Oxygen’s most popular Web sites. “She helps people with their relationships through humor and dignity.”

Humor and dignity are traits that Laybourne herself might need in the days ahead. “Generally do I think she’s in a great position? No,” says an executive at one of the companies with which she’s seeking an alliance. “I don’t think people are coming out and saying, ‘Oh, my God, everything she’s done is spectacular.’ ... When Gerry went to Disney she could have gone anywhere; it was ‘Gerry the Indestructible.’ Now she’s sitting with what looks like damaged merchandise. If it were trading as a public company, you would assume that the stock would be way under what it was a year ago.” Leo Hindery also seems to acknowledge Layboume’s problems. “What if she’s a total bust? So what? She tried,” he says. “I think she’s going to be wildly successful, but even if she’s not, she tried with quality and honor and passion. Isn’t that enough?”

For Geraldine Laybourne, the answer is a resounding, defiant “No.” After I bid her good-bye and am about to leave, she walks back over to me—whether spontaneously or according to some script, I cannot tell—and looks me in the eyes. “Remember, this is a marathon, not a sprint,” she says. “I’m in this for the long run. We’re going to go all 26 miles.”

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now