Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now"I come from a country that no longer exists. You see, I come from Afghanistan."

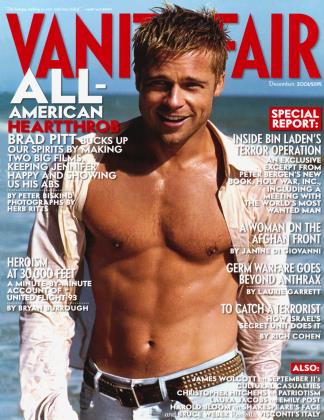

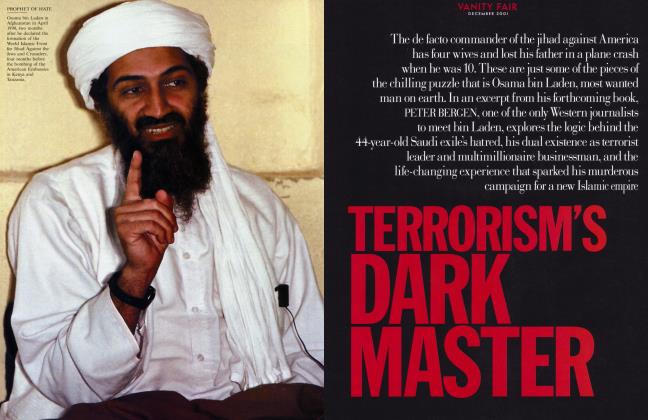

For longer than two decades, Afghanistan has known nothing but war and treachery: invaded by the Soviet Union in the last great battle of the Cold War, controlled by the militia of young Koranic students known as the Taliban, and now caught in the conflict between the United States and Osama bin Laden. From the ravaged countryside, where the Northern Alliance fights the Taliban and where a handful of women struggle for human rights, JANINE DI GIOVANNI reports on the fear, tragedy, and enduring spirit of a nation that is barely a nation

December 2001"I come from a country that no longer exists. You see, I come from Afghanistan."

For longer than two decades, Afghanistan has known nothing but war and treachery: invaded by the Soviet Union in the last great battle of the Cold War, controlled by the militia of young Koranic students known as the Taliban, and now caught in the conflict between the United States and Osama bin Laden. From the ravaged countryside, where the Northern Alliance fights the Taliban and where a handful of women struggle for human rights, JANINE DI GIOVANNI reports on the fear, tragedy, and enduring spirit of a nation that is barely a nation

December 2001THE AFGHAN FRONTIER, October 6, 2001.

The flat barge that carries passengers across the Amu Dar’ya, the river that separates Tajikistan from Afghanistan, takes less than 10 minutes, but the journey is into another world. The Amu Dar’ya, also called the Oxus, was the former boundary between the Russian and the British Empires, and even now, 82 years after Afghanistan’s independence from Britain was established, the land around the river has a feeling of being on the edge of the world. In the darkness, the only light comes from the full moon and from fires burning on the banks of the Afghan side. Soldiers huddle around them, casting strange, distorted shadows.

It is three weeks since the attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon. American forces have been massing in this part of the world, some kind of action is expected soon, and the Russian soldiers who patrol the Tajik border and check passports by flashlight at the barge dock are jittery. On the other side of the river, the passport control is a shack in which three Afghans sit cross-legged around a petrol lantern, their automatic rifles resting on their laps. The man checking passports leans forward, points to my hair, and shakes his own head violently. This is northern Afghanistan, not under Taliban control, but I am still supposed to wear a headscarf, and I forgot.

It takes two hours by ancient Soviet jeep to reach Khoje Bahauddin, an outback town in the province of Takhar that has become the provincial seat of the Northern Alliance since Taloqan, the Takhar capital, fell to Taliban troops last year. There is no road to Khoje Bahauddin, only tracks in hardened dust. The jeep shivers, sputters, and finally grinds to a halt after an hour, in the middle of the desert. As the driver argues with a companion about how to fix it, I fall asleep, huddled against the cold metal of the jeep.

When I awake an hour later, back on the “road,” I recall a conversation I had two decades ago in a post office in Parioli, an affluent Roman neighborhood. I had met an elderly man. We were both waiting to use the public telephones. His clothes were shabby and foreign, and he had the troubled eyes of someone who was far from home. I asked him where that was. His long face sagged.

The soldiers are immune to living in a state of war. When a round of gunfire bursts, they run toward it, laughing, howling, raising their guns.

“I come from a country that no longer exists,” he said after a pause. “You see, I come from Afghanistan.”

I understand the impact of his words only now that I am here, in a country of many sorrows, a country that has been buried alive by outside invaders, by war, by famine, by history.

Afghanistan, peopled by dozens of frequently antagonistic ethnic groups, is one of the poorest nations on earth. Its modern history begins with the invasion of India by Nader Shah of Persia, after which the Mughals lost control of all their territories west of the river Indus. In 1747, after Nader Shah was assassinated, a 23-year-old member of the Durrani Pashtun tribe, the country’s largest, fought his way back to his homeland and founded a kingdom in the territory that would become Afghanistan, establishing himself as King Ahmad Shah Durrani. The Russian czars had designs on Afghanistan but were thwarted by Great Britain, which took precarious control of the region in the early 1840s and then again in 1879. It was the British who in 1893 first drew the modern border between Afghanistan and Pakistan (which was then part of India), in the process sundering the homelands of some Afghan tribes. But the British never had much of a handle on Afghanistan, and after a third attempt at taking control in 1919, they finally gave up.

Afghans are proud of the independence they won that year, but strategically they remain highly vulnerable, surrounded as they are by Iran, Pakistan, and China, with Russia and India on the near horizon. The country’s recent history has been one of conflict and treachery, beginning with the peaceful Soviet-assisted overthrow of King Zahir Shah in 1973 by a cousin of his, former prime minister Mohammad Daoud. A subsequent Marxist coup and increasing unrest among Islamic nationalists provided the pretext for the 1979 Soviet invasion. On Christmas Eve that year the Red Army seized Kabul’s airport, and four Soviet motorized divisions rolled over the border. The country soon descended into a savage war, one in which teenage Russian soldiers fought against mujahideen fighters—Afghanistan’s anti-Soviet, U.S.-backed shock troops. This was to be the last great stand of the Cold War, and the scars of this 10-year conflict still cut deep into the Russian soul, that nation’s version of Vietnam. As the late Russian journalist Artyom Borovik wrote, “Afghanistan became part of each person who fought there. And each of the half-million soldiers who went through this war became part of Afghanistan—part of the land that could never absorb all the blood that spilled on it.”

By the time the last Soviet tank rolled back over the bridge separating Afghanistan from Uzbekistan in 1989, the country had been devastated, and was ripe for a series of new battles in which rival warlords and the country’s nominal government fought over the last remnants of Afghan nationhood. By October 1994, vulnerable to anyone who would promise its residents a better life, the southern city of Kandahar fell to an obscure militia of religious students, or Taliban, led by Mullah Muhammad Omar, who called for 4,000 volunteers from Pakistan. Some of the Taliban (the plural form of the singular, Talib) were former mujahideen, but the majority were young Koranic students drawn from the hundreds of madaris (Islamic theology schools) that had been set up in Afghan refugee camps in Pakistan.

By 1996, 1.5 million people had been killed since the 1979 Soviet invasion. Weariness, fear, and desperation opened the doors to the Taliban. In September 1996, when Kabul fell, they were first welcomed as liberators. But the world watched in horror as Najibullah, the Communist ex-president, was tortured and killed. (Like many Afghans, he used only one name.) Slowly and methodically, the Taliban plunged the country into their vision of seventh-century Arabia, of life in the immediate wake of the prophet Muhammad. This was a new agenda for Islamic radicalism. Afghanistan was declared “a completely Islamic state,” and the door to the West, to progress, to any kind of advancement, was abruptly slammed shut. Life under the Taliban became life behind a shroud. Girls were banned from schools. Women were forced to wear burkas—head-to-toe garments even more extreme than the traditional Muslim veil—in which they could barely see or hear, and were more or less ordered to stay at home. Men were commanded to grow beards long enough to grasp in one’s hand, or else be imprisoned. Television, playing cards, music, and photography were banned. If a woman’s shoes made too much noise, she would be beaten, because this was said to incite lust in men. Intellectuals were repressed and jailed. Public executions, stealings, and lashings took place to the glee of the Taliban soldiers, who provided security with their Datsun jeeps and Kalashnikov assault rifles. Money poured in from Arab benefactors.

Gradually, the Taliban, most of whose members are Pashtun, took more than 90 percent of the country. The intellectuals who could flee did so; the ones who could not chose to live underground and draw as little attention to themselves as possible. The remnants of the government that had been pushed out of Kabul by the Taliban in 1996 began to form a loose opposition under the command of Ahmed Shah Massoud, the son of an officer in the old royal army. Massoud’s troops, the Shura-eNazar, had been the strongest force during the war against the Russians. Now, he re-formed his largely Tajik and Uzbek army, dubbed the Northern Alliance or the United Front, along with the men of other commanders who were intent on laying aside their rivalries and banishing the common enemy—the Taliban.

For six years, the Northern Alliance worked alone, with some assistance from Russia and Iran, but it was largely ignored by the West. Massoud tried to rally support, but aside from France, where he was a popular, romanticized Resistance figure, no one in Europe or America took much notice of the Afghan opposition. On September 9, 2001, two days before the attacks on America, Commander Massoud met with two “Belgian journalists” in Khoje Bahauddin at the alliance’s headquarters. One of the journalists—they were, in fact, North Africans and are suspected to have been members of Osama bin Laden’s al-Qaeda terrorist network—carried a video camera, inside of which was hidden a bomb. Leaning forward, one man posed a question to Massoud: “And what will you do with Osama when you get him?” Massoud moved to answer, and the cameraman detonated his device. Massoud, who was called “the Lion of Panjshir,” was dead, and with him went the West’s great hope of a charismatic leader who could stand up to the Taliban.

In Khoje Bahauddin, when I finally arrive at headquarters late at night, one of Massoud’s former bodyguards, Nasir, a young soldier from the Panjshir Valley, leads me with a lantern to find a space on the floor to sleep. In the morning, he smiles and shows me where to find water that a donkey had carried up from the river below the village. He sits quietly with me, staring at the blackened room, a bombed-out shell, where Massoud was killed. The blood of Massoud and the suicide bombers is still splattered on the wall.

In the next room, I eat breakfast with the soldiers who guarded Massoud. We sit on the floor, and they share their bread and tea, motioning for me to take more, and to dip the bread into Russian cream that they pour from a carton. “Eat, eat,” says one. “Before the ...” With his hand, he playacts firing a gun. “Before the fighting.”

When I point to the blackened room, the soldiers grow silent. “They killed our leader,” Nasir says, the gentleness of his face suddenly turning to something hard, something vengeful. “Now we will fight them until we die.”

FRONT LINE, THE KALAKATA HILLS, NORTHERN AFGHANISTAN, October 7.

It’s some 20 kilometers from Khoje Bahauddin to where Northern Alliance forces are massing for an expected offensive against the Taliban. The front runs along a 30kilometer line, trenches dug into dusty hills. But before you get there you pass a cemetery. Mounds of earth, dried to dust, are neatly lined up, covering a large field. There are no markers, but under each one is a body, a reminder that war is hardly a new phenomenon here.

In Afghanistan, the average life span for a male is 46 years, and the soldiers here are so immune to living in a state of war, so immune to seeing death and mutilation, that when a round of automatic gunfire bursts over this frontline position no one cowers inside the trench. Instead, they run toward it, laughing, howling, raising their guns over the trench. A tank shell is fired from a nearby hill, and the thud silences them for a moment. But they seem totally untouched by fear. The ability to value their own lives seems to have disappeared.

The shooting stops around midday and the men begin to pray. They are largely uneducated. Many are refugees who fled the Taliban as their troops gradually moved northward from Kabul, taking more and more Afghan territory. The alliance has held onto roughly 10 percent of the country, in the northern provinces, and fights with what little equipment it has—a few helicopters, old Soviet weapons, hunting rifles. And yet, according to military observers, its men are some of the bravest fighters in the world. Russian soldiers feared them and called them dukhi, or spirits, because of their ability to ambush and run away, hide, disappear.

Some are old enough to have fought in the former king’s army. Some of them fought with the mujahideen. Some of them fought with the forces of former president Najibullah. All of them fought, sometimes against one another. Now they are united against a common enemy. “It was a mistake that we made, fighting each other,” says one commander, Isak. “Now people must agree with us—we have to make a strong government.” Like a lot of the commanders, he is grateful for but slightly suspicious of the attention that is now being paid to his country. “Before the bombing in New York, we fought the Taliban, and no one knew us, no one cared, no one gave us help,” he says. “Now there is an attack on America, and people want to know who we are.”

"Before the bombing in New York, no one knew us. Now people want to know who we are’

Mazar-e-Sharif is a strategically crucial city in the North, the capital of the Northern Alliance before it fell into the hands of the Taliban in 1998; it is about 100 miles from here and the ultimate goal of the coming offensive. For the time being, the front lines are only being reinforced. Hanging on the backs of old Soviet trucks, more soldiers arrive, some in battered American-made fatigues, others wearing traditional Afghan dress— knee-length shirts over baggy trousers—along with padded gray parkas and slip-on black shoes caked in dust. Over their shoulders they carry old Kalashnikovs, around their waists ammunition. These are hardened fighters, and yet there is a strange innocence to them. Unaccustomed to seeing a woman without a burka, which is traditional in the North though not mandatory, they stare at me as if I were a television set, and gather in groups, whispering and holding one another’s hands—a common sight among men in Muslim countries. They make me eat lunch with them, “a soldier’s lunch” of rice, beans, grapes, and nan, the flatbread that is a staple in the Afghan diet. During the meal they talk, and the talk is always about war.

The “ dushman”—the enemy, the Taliban—have reinforced their own front lines with Chechens, Pakistanis, and other recruits who have come to fight the jihad. “Foreigners,” the Northern Alliance soldiers snort with disgust. “We are fighting foreign forces, Osama’s forces,” they tell me, quick to point out that bin Laden is not an Afghan but an Arab. To compensate for the Taliban’s strength, the Northern Alliance now claims its ranks have swelled to 12,000, and its spokesmen claim that the enemy troops are defecting, every day more of them crossing the lines.

I leave the front to visit Commander Dagarvol Shirendel Sohil, who oversees a Northern Alliance defensive position on top of a hill in an area known as Ai' Khanum. Below this position is an abandoned mud-hut village. The people there, fearing the sound of outgoing tank shells, fled when fighting began in the area earlier this year.

“Our soldiers are stronger,” says Commander Sohil. “Up until now, the Taliban were supported by foreign money. Now they have a choice. Join us, or die.” At the foot of his camp, which is littered with empty 100-mm. tank shells, are Greek ruins dating back to the time of Alexander the Great, yet another foreign invader. It is a surreal sight to see an old Soviet T-55 tank near an ancient Greek urn.

"We are fighting foreign forces, Osama's forces” the soldiers say, quick to point out that bin Laden is not an Afghan but an Arab.

“You forget, this was a beautiful country,” says my translator, Ahmad, a 24-year-old Afghan whose father was an important mujahideen commander. He was killed fighting the Russians when Ahmad was 2 years old. Ahmad’s 12-year-old sister was killed during the war against the Taliban. He swallows these tragedies with a shrug of his shoulders. “Yes, it is sad,” he says, “but I am used to it by now.”

Ahmad lost his childhood. Like many sons of the Afghan elite when the country was under Communist rule, he went to Russia to study when he was eight, along with his two younger brothers. They were meant to go for one month, to absorb Soviet culture, But one month became four, four months became a year, 5 years, 10 years; the boys were housed in an orphanage. “After President Najibullah fell, they forgot we were there,” Ahmad says casually. His mother had no idea how to get her sons back; they had no idea how to return to their country. “At first, we were too small, then we forgot what it was like to be Afghan,” he says. He was 22 when he finally saw his mother again last year. At first, she did not recognize her eldest son; then, when it was clear who the stranger standing in front of her was, she burst into tears. He had to relearn Dari, the language spoken by most Afghans. Two months after his return, Taloqan, his city, fell to the Taliban. He fled; his mother stayed. There are no telephones, no communications, so he has no idea how or where his mother is now.

Ahmad takes my map, bought in London, and points out our location at Ai' Khanum. Underneath, written in red, is “Excavation of Greek ruins.”

It is odd to think of this country as having had Hellenic life, having had civilization. But farther south on the map there are markers for more former tourist attractions: near the city of Charikar, “Picturesque Bazaar, Ceramics,” and closer to Kabul, “Climatic Health resort.” Through the Paghman mountain range, near Bamian, there are two sites of interest. One offers “Scenic Beauty, differently coloured lakes.” To the east, marked with a star: “Giant Buddha sculptures.” But a word has been added underneath: “destroyed.”

The map does not say when or by whom. It was, of course, the Taliban, who last March dynamited the ancient and monumental stone Buddhas, remnants of the country’s layered history, in pursuit of their completely Islamic state.

From the top of the hill, the Kokcha River winds down through flat rice marshes and past a series of Northern Alliance positions. Crossing the river, I return to the line, to a position near the village of Jilin Hur. Here, the soldiers move on horseback, and the biblical landscape swirls with dust. The Taliban are about a mile over a hill, and you can see the Northern Alliance’s mortars land on the Taliban positions, sending up plumes of smoke. Their trenches, dug into a hill, look like a seam on a dress; around the seam are buttonholes where Northern Alliance shells have landed. When return fire rips past, I crouch in the trench, then lift my head to see shadowy stick figures—the Taliban, the soldiers tell me—manning their distant position.

Night falls. I am returning to Khoje Bahauddin with soldiers and some other journalists. We cross the Kokcha by military truck, which wades through the river, the water rushing up to the bottom of the door. The sky for the first time seems clear. The dust storms, which were preventing helicopters from bringing supplies, have quieted. There is a stillness to the air. It is perfect bombing weather.

After a one-hour drive over yet another series of ruts that passes for a road, bumping over holes gouged into the dry earth, I am back in the alliance headquarters. The soldiers and the officials are gathered around a television intermittently powered by a generator and tuned to CNN. On the screen, there are snowy images of white lights blinking over Kabul.

“Bombs,” says one soldier, and the others lean forward. It is the first night of the U.S. and British attacks. We watch in silence. Though the allies are attacking the Taliban, there is no jubilation here among the Northern Alliance troops. Someone asks the soldiers if they are happy. “They’re bombing the Taliban,” someone says. “But they are also bombing our country.”

DASHT-E-QALA, NORTHERN AFGHANISTAN, October 8.

This grim village was once surrounded by farmland, but there has been no rain here in the North for three years, and so there is no harvest. Fields that were once full of wheat are now pale dust beds, caravan routes for donkeys and camels. There is hardly any fresh food for sale in the area’s markets; beggars and children covered in scabs and dust pick the remains from rice bowls and beg for nan. An orange is a strange and foreign thing.

Entire towns are emptied, most of the inhabitants having fled the fighting, the famine, the disease. Tuberculosis, cholera, and malaria are on the rise, and with the heavy snows expected in about six weeks’ time, the few aid organizations that are here are fearing the worst. If it were not for the Agency for Cooperation and Development (ACTED), a French nongovernmental organization that distributes wheat, no one would eat.

Most of the international charity organizations, except ACTED, left after September 11, but a team of German doctors have arrived. “It is an emergency,” says Rupert Neudeig, whose group is trying to establish a clinic here before winter closes the roads. “I say ‘clinic,’ but it will only be a shadow of what you think of as clinic,” he explains with resignation; the reality is that saving this country is a Sisyphean task.

In the bazaar at Dasht-e-Qala, men sit drinking green tea, and a lone child carries a bag in which she stuffs pieces of fat and rice that have fallen on the floor of a kabob cafe. Like clinic, “cafe” is too grand a word. It is a dusty room where the men sit crosslegged on the floor, and plates of meat, seared on iron sticks, are placed in the middle of the floor with a stack of nan. There are no women in the bazaar, let alone the restaurant.

There is a group from Kabul, refugees. One of them, Khaled, comes over to practice the English that he learned in secret—a very expensive course, he says, which cost $10. “Everyone wanted to learn English in Kabul,” he says, “so they could run away.” Khaled hated life under the Taliban, hated the fact that he could not listen to music, could not meet his friends, and had no hope for a different life. At 17, he could also not grow a full beard. When the religious police caught the barefaced teenager on the street one day, they threw him in jail for a week.

“I told them I wasn’t old enough to grow a beard, but they didn’t believe me,” he says. After that, he didn’t walk around the city so much.

Here in the North, people listen to Radio Mashhad, broadcast in Dari from Iran. That country, with its mostly Shiite Muslim population, is no friend of the Taliban, who are predominantly Sunnis. Radio Mashhad gives locations of the allied bombing raids: Kabul, Kandahar, Mazar-e-Sharif. With the bombing, however, there is no chance of aid being delivered from Pakistan.

Because there is nothing, people make things from nothing. In the corner of the bazaar, a metalworker named Ustaboba is fashioning shovels, hinges, and nails from the remnants of 100-mm. shells. He buys three shells for $1, sells a shovel for $3—a war profiteer. What he is doing does not seem so odd to him. Before him, his father did the same thing, using shells from the AfghanSoviet war. And besides, he cannot imagine a life without war.

KHOJE BAHAUDDIN, October 9.

To be a woman in Afghanistan can mean a life of constant struggle. Or it can mean that you simply don’t exist, that you are invisible, that you live through a burka.

The first thing I notice about Farahnaz, a refugee from Kabul, is the way she walks through the dusty courtyard of the relief agency where she works. She is proud and defiant, her head high, not dropped low like those of the other women—the very few women—I have seen since I arrived in Afghanistan. The second thing I notice is that she is not wearing a burka, only a headscarf. As we talk, the headscarf falls forward, and under it she has a shiny ponytail and a smooth, high forehead.

On March 8, International Women’s Day, Farahnaz founded the country’s first women’s center here in Khoje Bahauddin. If this were not Afghanistan, a land bound by tradition, that would not be extraordinary. But to have a women’s center in a country without women’s rights—the Northern Alliance is only slightly better than the Taliban on this score—is unthinkable. Still, she tries. She wrote to the provincial governor for help in teaching local women the Koran and basic health care. He responded by closing down her small women’s center. Now she conducts meetings in secret where women can study English and hygiene.

Her husband was threatened by the local government because of her work. “I went to the authorities and said, ‘If you have something to say, you say it to me. I am running the center, not my husband.’”

Her husband supported her in this, even though he did not support her when she refused to wear a burka. This was because she had spent years wearing Westernstyle clothes when she studied electrical engineering in the Ukraine. Even her husband’s fury could not convince her. “I couldn’t see, I couldn’t hear, I kept falling down!” she says of the burka. “And more important, I must set an example to other women.”

If you are a woman in Afghanistan, even in areas not held by the Taliban, you are lucky if you get to go to school. And even if you do, the resources are limited. There is only one university for women in the entire country, in the city of Feyzabad; it is so badly equipped that medical students who finish there are not skilled enough to operate even on corpses.

But before the wars ravaged this country, life was different, at least for the elite. When Kabul fell to the Taliban in 1996, Farahnaz, her husband, and their two children, a boy and a girl now aged 17 and 10, fled to Pakistan, where they stayed for nearly four years. Farahnaz learned English, studying alongside her children. The family returned to Talibancontrolled Afghanistan last year, but soon fled again, this time by donkey, to the North. For three months they were trapped in an obscure valley where they had only rainwater to drink. Farahnaz watched mothers feeding babies the dirty water, she watched the babies get sick, and she tried to do something to help, to teach them.

Finally, she arrived in Khoje Bahauddin, where she realized she was one of the few educated women. She told the local women that there was another world where women went to work outside the home, and that they could free themselves through education.

Talking to Farahnaz in her small, whitewashed home, I realize how lonely she must be, how she must feel like an alien, how out of sync her ideas are with those of the other women here, most of whom simply accept the miserable fate that life has dealt them. Farahnaz looks down at her lap. It is lonely, she says, but there are small satisfactions. There are now 100 women in her group. “I can’t help these women economically, but I can help by opening their eyes, giving a different vision of the world.”

Down the road, at a small women’s workplace run by ACTED, a group of women, most of whom are war widows or married to men unable to work, have formed a collective that sews clothes and quilts. For each article of clothing, they get five kilos of wheat.

They all sit cross-legged in front of ancient Chinese Butterfly sewing machines, and when I enter the room, they stare and giggle. One of them grabs my hand. “Taliban! Taliban!” she says, squeezing it so hard it hurts. She pantomimes holding a gun at her head. “Her husband was killed by the Taliban,” explains the director, Fahima Murodi, who is the mother of seven, four of whom are girls, and has a master’s degree in economics from a Russian university. Despite her education, and the fact that she says the most important thing she can do for her daughters is to fight for their education, she still wears a burka.

“But we want change. We want things to be different,” she says. “We want to be free! We want to develop ourselves. But it is hard in a place where there are no opportunities for girls to be educated after the age of 14.” Then she takes me outside to meet another girl working there, who has a plastic leg because she stepped on a land mine. Both her parents were killed in fighting. She has no brothers and sisters, so the village helps look after her. The girl, Asyla, rolls up her long dress to show me her leg. She speaks a few words of English. One of them is “war.”

Back at her home, Farahnaz insists to me that she is not going to give up. She says this when her daughter, Vida, a miniature replica of her mother, enters the room. The child speaks perfect English and tells me she wants to be a doctor when she grows up because she wants to help her country. Then she recounts a long story about the Taliban’s beating women, growing more excited with the injustice of it all, and I look at her and wonder what she will be like in 10 years, and how different the country could be if more mothers produced children like this.

As I leave, I ask Farahnaz what it feels like not wearing a burka. She got stares at first, she says, when she went out without one. Now she gets few looks, because the people in the village know how much she does to help people. “I think they respect me,” she says. “Some of them call me Mother.”

FRONT LINE, QUR‘UGH, October 10.

It is a hot autumn day, and the news is that Northern Alliance fighters have taken two strategic villages close to Mazar-eSharif and are now six kilometers from the city. The allied bombings are moving closer to the Taliban front line and its infantry. Dr. Abdullah Abdullah, the Northern Alliance’s foreign minister, says this is a new phase of the war. Something is turning.

Yesterday, to get to the front here in Takhar, I crossed the Kokcha River on a frightened, shell-shocked horse with rope for reins, led by a teenage horseman. Today a military truck arrives, and I catch a ride in somewhat more comfort. I sit in the front, between two soldiers who sing quietly under their breaths—religious songs, for Allah, they say. We take a dirt road that leads to a different front line. From there we get out next to a bridge by a turn in the river and walk. A commander, not pleased by my presence, says, “We are close to the enemy. If you get injured, what happens then?” An outgoing tank shell explodes somewhere, and I say nothing. The walk continues through rice fields and a field of bursting cotton plants, and someone says not to stray off the path.

“Mines.”

The lush cotton fields look surreal in this otherwise wasted landscape. A soldier bends down and picks up one of the soft, fuzzy plants. When he gives it to me, he laughs and rubs it against my cheek. The soldier in front of me is barefoot and carries a light machine gun. He is 17, shy, does not look in my eyes, but he is singing in Dari as we march single file.

At the front, the dushman are close, so close that one of the soldiers points to a moving object and says in an excited voice, “Taliban! Datsun!” We crouch and watch the dushman, and the commander tells us to go quickly now, because they have spotted our position. So we walk back from the trenches, through a field of rice, another of cotton, past donkeys and soldiers on horseback and blooming trees. We pass a lone grave next to the river, a commander’s. Women have come and wrapped tattered, colored cloth around a tree. “So we don’t forget him,” one tells me.

We arrive at a command post. The soldiers there make us drink green, sugared tea and eat coconut biscuits from Iran. Outside is a small oasis of flowers: pink gerberas, what look like red dahlias. One of the soldiers has a tame blackbird, a pet, on his shoulder. On the wall, in charcoal, they have sketched a beautiful woman inside a heart. She has long eyelashes and does not wear a burka or veil.

The colors of the day darken. Across the river, the hills where the lines are seem to fade in the dying light, and the sky shakes slightly with a shell falling somewhere. I think of a group of young soldiers I saw earlier in the week, who had scrawled something on a wall. Ahmad had translated it for me:

We wait for tomorrow

For the victory against the Taliban

Our brother Talib

Sold our country to the foreigners.

Next to the command post is a small triage hospital, two beds under a tarp. There is one blanket, and the medical supplies consist of a box of ancient field dressings and a bottle of Russian disinfectant. That’s it. When someone is injured, they have to carry him across the river, by donkey or horse, and then drive an hour to Khoje Bahauddin over the tracks that jar every bone in the body, even if you are not injured.

“All we can do is stop the bleeding,” says the triage nurse, a young boy of 18 or 19. “We just stop the bleeding.”

I’m driven back over the river to the front, into another night of bombing, this time near Taliban infantry lines. Some of the alliance soldiers are angry because they don’t know if their families in Mazar-eSharif and Kabul and Taloqan are dead or alive. I can’t keep the image of a bleeding soldier being carried by donkey over the Kokcha River out of my mind, and then I realize the bleeding soldier is really an analogy for this country. I have never been in a place so stained with its own blood. And all we are doing, all we can do, is stop the bleeding.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now