Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThis recently discovered portrait, painted four centuries ago—and soon the subject of a forthcoming book and exhibition—may reveal the true likeness of our most legendary poet and playwright. Pre-eminent literary critic and Shakespeare scholar HAROLD BLOOM is moved to ask: Why the urge to put a face to such genius?

December 2001This recently discovered portrait, painted four centuries ago—and soon the subject of a forthcoming book and exhibition—may reveal the true likeness of our most legendary poet and playwright. Pre-eminent literary critic and Shakespeare scholar HAROLD BLOOM is moved to ask: Why the urge to put a face to such genius?

December 2001When we visualize Shakespeare, we tend to remember the print by Martin Droeshout used for the frontispiece of the First Folio of the plays (1623), seven years after the dramatist’s death, presumably taken from a sketch now lost. This Shakespeare is high-foreheaded, long-nosed, and commonplace, if not plain. There is also the bust on his church tomb in Stratford-upon-Avon, rather bland, and the disputed Chandos portrait in the National Portrait Gallery, London, which scarcely resembles the Folio engraving or the tomb sculpture, since its subject appears to be more Italian or Spanish than English.

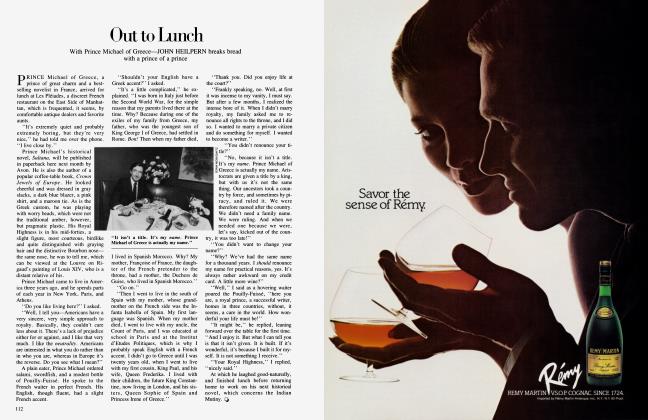

Now comes the so-called Sanders portrait, reproduced here on the magazine page for the first time in its original splendor. (The painting is the centerpiece of a traveling exhibition and a book, Shakespeare’s Face—both appearing next year—on the Bard’s elusive image.) This rendering came to light only this May, brought forth by a Canadian engineer who asserts that this purported likeness of Shakespeare, possibly the only portrait of the playwright created during his lifetime, has been in his family these 400 years, having been painted in 1603 by John Sanders, thought to have been a minor actor in Shakespeare’s company. Shakespeare would then have been 39, but there is no clear record of such an actor. That in itself proves little, and the recent authentication of the Sanders portrait establishes only that it is indeed some four centuries old. The sitter seems youngish for a man of 39, but all we can know with certainty is that it is either Shakespeare’s face or one of his contemporaries’.

I do not suppose that we ever will know whether this “new” portrait actually is a representation of William Shakespeare, 1564-1616, poet-playwright and actor-manager, who was born in Stratford, pursued his extraordinary career in London, and then went home again, to retire and to die.

Why do we care what Shakespeare looked like? The traditional portraits of him have no particular authority, and I prefer this new one, since it is livelier. There seem to me two particular reasons why we care: Shakespeare’s unique eminence, and our total lack of authentic knowledge as to his personality and character. We simply do not know anything about the inwardness of this inventor of our inwardness. His only son died young, and his two daughters survived him, as did his wife, Anne Hathaway, with whom his relationship seems not to have been particularly close. Though it is fashionable these days to discuss his supposed bisexuality, there is no evidence for that beyond the highly equivocal sonnets, a superb poetic sequence but profoundly detached in regard to its speaker. In any case, the destructive passion expressed for the mysterious Dark Lady of the sonnets is far more intense than the affection for the fair young nobleman who may have been Shakespeare’s patron, the narcissistic Earl of Southampton.

Since we know nothing but the public facts about Shakespeare, we are ever vulnerable to fresh “discoveries” that are not invariably reliable. A perpetual barrage is maintained by the Oxfordians, for instance, a fierce coven who insist that the Earl of Oxford wrote all the plays attributed to the actor they dismiss as the “man from Stratford.”

It is reasonable to suppose that Shakespeare wrote Shakespeare, which brings me to his merited standing as the greatest of the world’s writers. We know how Tolstoy and Walt Whitman, George Eliot and Virginia Woolf (a great beauty) looked, and the image of them in our heads sometimes helps inform our reading of their work. But Shakespeare, as Jorge Luis Borges wrote, seems at once to be everyone and no one, and perhaps no image of him could be adequate to his universal relevance. He was a successful actor but not the hero or hero-villain, or the clown: evidently he was what we now call a “character actor.” He played many roles, but the ones we definitely assign to him are the Ghost in Hamlet and old Adam the servingman in As You Like It. Even more than an authentic portrait, I wish desperately we had a recording of his voice reading or acting. Was it high or low, strong or secondary? How did the Ghost sound, opening night at the Globe Theatre, when Shakespeare cried out “List, list, O list!” to Richard Burbage, playing the part of Hamlet?

We can surmise that Shakespeare invested himself more heavily in Hamlet than in any of his other characters, but not in the mode of self-portraiture. The evasive, true Shakespeare, for me, is the thin fellow inside my hero and double, Sir John Falstaff, who on the battlefield utters his great motto: “Give me life.”

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now