Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowIN THE DOT-COM DOLDRUMS

THE NEW ECONOMY

With the NASDAQ meltdown, the brash young C.E.O.'s who strutted the business-world stage like rock stars have turned into walking punch lines. And a generation wonders what happened to its American Dream of retiring young as options millionaires

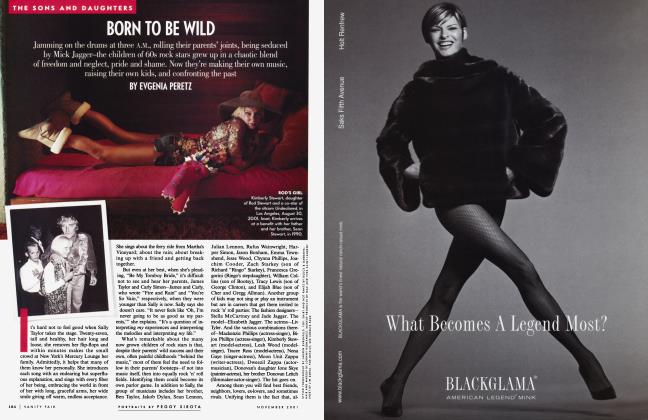

EVGENIA PERETZ

For anyone interested in Josh Harris’s new sweater, you can log on to www.WeLiveInPublic.com and look at it. You can also look at him reading on the toilet, and look at his girlfriend, Tanya Corrin, eating peanuts. That’s because there are 32 cameras recording everything that Corrin and Harris—founder of Silicon Alley’s flashiest dot-com, the now defunct Pseudo—are doing, saying, wearing, watching, and consuming, in every corner of their 4,000-square-foot Lower Manhattan loft, 24-7. It’s an art project, explains Harris, a feverish man-boy of 39. It’s “the last leg of the celebrity paradigm,” and it represents “the juncture of human existence.”

Maybe so. But it’s a far cry from what Harris had in mind on February 15, 2000, the night he appeared on 60 Minutes II. Trumpeting his brainchild, Pseudo, which offered 200 channels of superedgy streaming video delivered free to your desktop, Harris warned correspondent Bob Simon, “I’m in a race to take CBS out of business.” Now, with the programming options down to Josh emptying dishwasher, Josh taking nap, and Josh clipping toenails, Simon and his colleagues at CBS can sleep soundly.

Like thousands of others who once counted on making it big on the Internet, Harris is taking a crash course in how to live in an age of severely diminished expectations. At one point worth $80 million on paper, Harris now says, “I’ve thought about going broke_It’s a constant thing.” He admits that soon he’ll have to start charging his viewers. Presumably, he is talking about the roughly 100 people logged on tonight, many from Sweden.

Setting up WeLivelnPublic has cost Harris upwards of $1 million, and because he and his girlfriend literally live on-line, the Internet-access bills run about $200,000 a month. And for what? Corrin usually waits until yoga class to go to the bathroom, and she says she hasn’t had sex with Harris since an aborted attempt last summer, when they gave WeLivelnPublic a test run.

Can anyone forget what life was like in 1999? Not only could I a manifesto such as Harris’s “We’re in the business of programming people’s lives” fly as a business plan, it could also get venture capitalists worked into a big lather and ready to part with $16 million. At the same time, kids such as Jeff Dachis and his Hebrew-school buddy Craig Kanarick, who created the Internet consulting-and-design firm Razorfish (whose mission is to “recontextualize” businesses), suddenly found themselves with hundreds of millions in stock and the opportunity for majorleague makeovers. Kanarick cut the stringy long hair, threw out the Coke-bottle glasses, and started wearing lots of grape, while Dachis, a onetime gypsy dancer, bought two motorcycles and started saying things like, “There are sheep and there are shepherds, and I fancy myself to be the latter.”

As it turned out, a lot of sheep thought they were shepherds. Harvard Business School students scoffed at the chump change to be made at Morgan Stanley and decided the real money was in, say, pencils.com. Some even dropped out of college to follow the parade. An entire generation got in on the act, hoping that they could parlay youths spent in front of the computer screen into a BMW, a big house—who knows, maybe even early retirement. Who could blame them? This was the biggest thing since television—no, since electricity. Suddenly, going dot-com became what writing a screenplay had been in the early 90s, and the Great American Novel before that.

But in the aftermath of the NASDAQ crash of technology stocks last April, with investors some $3 trillion poorer, “dot-com” is starting to take on the distinct ring of a punch line. In the past year, nearly one in five dot-coms has closed up shop, and more than 40,000 employees nationwide have been laid off. As a result, many seemingly visionary C.E.O.’s have found themselves shutting their overworked pie holes. Dachis, for once, declined to be interviewed— perhaps because the Razorfish stock has taken a dive, and the company is also joining the growing legions facing class-action lawsuits from shareholders. Out of the ashes, a depressing cottage industry has arisen, chronicling the dot-com flameout. The New York Post has a new section that tracks dot-com casualties, numerous new Web sites exist to keep us apprised daily of the unhappiness, and a monthly Pink Slip party has started in Manhattan, in which recently axed kids get to commiserate over Jamaican beer.

The requiems run the gamut from dreary to agonizing. Marisa Bowe, one of Silicon Alley’s rock ’n’ roll pioneers and founder of the artsy culture site Word.com, describes the atmosphere as one of “rudderless dread.” Meg Weber, a woman in her mid20s who was laid off from Pseudo and iCast, another streamingmedia site, compares the downfall to “telling a little kid that Christmas is all a fraud.” And here’s 34-year-old Bill Lessard, whose busy track record—seven jobs in seven years—has inspired him to co-write the new book NetSlaves and to go into the following bit of free-form drama therapy: “You ever see On the Waterfront? That’s how I feel-‘You take away your Palm pilots and your venture capital, and you’re nothing. You think you’re God Almighty, but you know what you are? You’re a dirty, stinking bum, and I’m glad what I done to you.’”

"I've thought about going broke.... It's a constant thing."

"If I had a prospective client coming in... I don't want to have him see the graffiti and people peeing in the elevator."

Is there anyone truly surprised by the mass disillusion? After all, this was an industry founded on the principle of: If you hype it, they will come. The valuations were absurd, the money was only “on paper,” and, with the exception of a few, the dot-coms themselves were fueled by a lot of hot air. Confetti delivered in under an hour? Brilliant! One-click Kibbles ’n Bits? Go for it! Harris’s Pseudo wasn’t much more inspired. Its 200 programs included a wrestling show called And Justice for Brawl, Star Freaky, in which B-list celebrities were accosted at premieres by a bothersome young girl, and another program called Bugg Out, which, as one Pseudo employee described it, was, “for three hours, ‘Yo! Yo! \b!’” Not surprisingly, one show got only 29 viewers.

But if you were a potential investor, the fact that Pseudo was little more than cable access on a computer screen didn’t really matter. u invested in the mad vision of the young impresario. As Pseudo’s Jonas Goldstein puts it, “[Josh] is the product.” From the time he started Pseudo in 1994 to its end last September, Harris became famous for many things: there was his alter ego, “Luwy,” a greasy clown he liked to dress up as; his obsession with his lizard, Maurice; the phase he went through in which he wore a tie around his head. And then there were his downtown bacchanalia, which featured, in addition to drugs, everything from monkeys to gladiator battles. All of which made employees and investors feel that Warhol’s Factory had come again (this time with stock options). Harris’s most recent party lasted four weeks, took up three floors of a space he’d rented, and cost $ 1.1 million. It involved people wearing industrial-orange suits, public showering, group feasting, and live sex acts in which, as Marne McCutchin, Pseudo’s 31-year-old director of business development, remembers, “none of the guys could get it up.”

It sure was fun. But former Pseudo employees, even ones such as McCutchin who still kind of love Harris, admit that the aura of genius unbridled started to seem ridiculous. “If I had a prospective client coming in ... I don’t want to bring him up the stairs and to have him see the graffiti and garbage and people peeing in the elevator.” Meg Weber, an idealistic and bubbly feminist dressed in black, had her faith shaken, too. “I think [Josh] was starting to lose his appeal when that coolness factor was acknowledged,” says Weber, who interned at Ms. before joining Pseudo. “Once it was acknowledged, we were suddenly conscious. It was like being in the Garden of Eden and Finally noticing that we were naked. Everybody looked down, and I was like, ‘Ew.’” What happened next was a pattern repeated at dozens of other dot-coms. After burning through a reported $6 million a month, Harris stepped aside as C.E.O.; he was eventually replaced by David Bohrman from CNNfn, who couldn’t save it, and Pseudo ended up in bankruptcy court.

But perhaps no one felt the train wreck of dot-com fabulousness more than Seddu Namakajo. An excitable 27-year-old college dropout from Harlem, Namakajo was a business-development executive at two of the splashiest dot-bombs ever, the black entertainment site Urban Box Office Network (UBO.net) and Boo.com, an electronic fashion catalogue whose go-go 80s trappings are now legend: the Swedish former model Kajsa Leander and the Dieteresque Ernst Malmsten, who were co-founders; job titles such as “cool hunters”; a full-time concierge/chef; frequent dinners at Nobu; routine trips on the Concorde; and more than $ 125 million in financing from investors such as J. P. Morgan and LVMH. Naturally, Boo was featured in some 20 magazine articles during its first seven months in business. As Namakajo well understood, “the money follows the press, follows the hype, follows the party.” The trouble was, the Boo people, whom Namakajo refers to as “so Euro-elitist,” started to believe their own hype, privately claiming, it is alleged, “We’re going to be bigger than AOL.” But not everything worked out quite as planned. “The Web site opened a couple of days after Christmas. There were 30 orders, because the Web site didn’t work,” Namakajo recalls. “[Boo] had anticipated for that month 30,000 orders.”

While Namakajo had a gnawing fear that Boo was kind of a joke, he, like everyone else, couldn’t resist going along for the ride. “I’m the biggest consumer of all that shit. More than anybody,” says Namakajo, who enjoyed the company policy that allowed employees traveling abroad to fly a family member or partner over on Boo’s dime. “I flew my best friend out to London. I flew my best friend out who’s a janitor. An allexpense trip, all meals, to spend two weeks with me in London.” Hoping that one day he could parlay the options he received into $ 1 million, he purchased a Samsung entertainment system that’s not yet available in the United States, spent $15,000 on Christmas presents, and got some “really expensive Italian carpeting.” He also bought a house for his mother, and he started putting his brother through Wesleyan University. Namakajo, it appeared, had arrived. “I was the kid in the neighborhood that made it,” he says.

The dot-com boom was a chance for everyone to make it—and fast. Half the ’98 graduating classes from the Harvard, Stanford, and Wharton business schools went into the Internet industry, while tens of thousands of young workers brazenly left their jobs fetching lattes and staring at spreadsheets in their dust. “They had a conquer-the-world mentality,” says 25-year-old Andy Wang, founder of Ironminds, a general-interest Web magazine, which is now operating on no money. “Because they were smart enough to know that they didn’t have to climb the ladder. Somebody had built them an elevator.” Not only could a 25-year-old instantly become something cool, such as a “creative director,” he got stock options. “People were taking three and four and five dot-com offers, to see which one had the most stock options, and which had the quickest return. Everybody did the math,” says Andrew Goldberg, a 32-year-old Harvard Business School grad who started Eziaz, a provider of broadband access, which raised $50 million in venture capital. “There were people who joined us who used Eziaz stock for the money they were going to use to retire.”

Some others, among them 23-year-old New Jersey native Bill Martin, also got into the idea of being a junior-varsity titan. Last February he sold Raging Bull, the financial Web site he’d started in his parents’ basement, to Alta Vista for $167.5 million, mostly in stock, which he and his partners could cash in if and when Alta Vista went public. Since Alta Vista was already preparing to file for an I.P.O., it looked like a slam dunk. Martin was poised to become one of the richest dot-commers his age. He was featured on Oprah and was followed around for two entire days by 48 Hours, which he admits “was pretty awesome.” He also got itchy fingers. “For a little while, it was like Christmas morning was getting a lot closer and you’re getting a little giddier—‘I’m goin’ out and buyin’ a new car!”’ says Martin, recalling the excitement that led him to a new BMW.

Now, alas, an I.RO. for Alta Vista is unlikely, and while Martin still gets to talk to colleges about his entrepreneurial experiences, he also has to cope with, well, being a regular guy. “The difficult thing is people reading the paper: ‘Oh, your company was bought for $168 million!’” Not surprisingly, Martin is now thinking of going to Harvard Business School. “There’s a professor up there who invited me to go next fall,” he says, rather unenthusiastically.

The promised land has vanished, and what’s replacing it is not pretty. For most people the notion of trying another start-up is out of the question. “Oh, I’m going to become a product manager at some e-commerce Web site so I can sell shoes on-line?” says Lessard. “I could be the A1 Bundy of cyberspace—oh, boy!” And going “B to B” (“Back to Business”) feels kind of pathetic. “The prospect of starting over, of working for people who are probably younger than you, and having to go prove yourself working for 3 or 5 or 10 levels of management—I haven’t seen a whole lot of friends do that yet,” says another Internet casualty who is now at a crossroads.

The only viable option, it seems, is to drift. Indeed, the dot-com free fall has created a new lost generation of goal-oriented masters of detail who are now without a blueprint. Former William Morris agent Michael Dowling, 33, who started iFuse, a defunct Generation Y content venture, now spends much of his day hanging out at Starbucks. “I go there almost every day,” he says. “I do my thinking, I do my reading, I do my writing.” Kaleil Isaza Tuzman, 29, a Harvard grad who “always wanted to be better than the next one,” started Gov Works Inc., banking on the idea that people would want to pay their parking tickets and utility bills on-line. But when the value of his company tanked in the fall, so did his self-esteem. “I couldn’t go for a very long period of time without spontaneously bursting into tears,” says Tuzman, who also had the surreal experience of laying off his own father. “It’s totally decimated my ego.” And Meg Weber, who was recently awarded the title of “Dot-Goner Princess” at the Pink Slip holiday party, has been spending a lot of time wondering just what happened. “It was the ultimate lottery ticket,” says Weber. “Everybody wanted to believe. That is why it was so disillusioning and hurtful. Because it was more than just a job. It was people’s American Dream.”

"The people left holding the bag are all the young employees."

"It was the ultimate lottery ticket.... That is why it was so disillusioning and hurtful."

In addition to the paralyzing disappointment, there are the more practical problems: capital-gains taxes to be paid, bank loans coming due, houses and jets to be returned. Michael Donahue, 36, seems to be facing it all. When he took his e-commerce company, InterWorld, public in August 1999, he saw his stake rise to $448 million. He then reportedly borrowed $14 million, rented a private jet, and bought a $9.6 million second home in Palm Beach. Now his personal stake has fallen to $12 million, and the house is back on the market. Others, such as Dave Kansas, editor of TheStreet.com, the financial Web site whose stock has plummeted from $70 to $2.50, simply can’t maintain their purchases in the way they’d hoped. “I made spending decisions, a few that were based on a $10 stock,” says Kansas, a low-key, self-effacing 31-year-old who left his job as a reporter for The Wall Street Journal to join TheStreet, “and when you’re a $2 stock, you pay a price for that.” He is referring to the loft he bought for more than $1 million in Tribeca when his net worth stood at $ 12 or $ 13 million. Now, with a personal wealth down to a few hundred thousand, Kansas describes the whole new apartment thing as “a challenge. I have no furniture. I’ve become a big fan of minimalism.”

The shock waves have reached those at the very top, too, such as Michael Saylor, 35, of MicroStrategy, which makes “data mining” software for businesses. Last March, after MicroStrategy allegedly overstated its revenue, the stock fell from $333 per share to about $13. For the company’s top executives, that meant—in addition to a civil fine of $350,000 and $10 million paid to settle federal regulators’ allegations of civil accounting fraudsome heavy “soul-searching,” says Saylor. He decided to focus on “what we can do better than anybody else,” which Saylor calls “the business-intelligence business,” and jettison everything else, including the company-wide cruise, which in 1999 cost $3 million. And for Saylor himself, whose personal wealth dropped by $6 billion in one day, that meant putting his dream house “on hold.” Saylor had wanted it to look like the one in the movie version of The Great Gatsby. He had already purchased the 50-acre lot overlooking the Potomac River.

Saylor can handle the house part. What’s harder is swallowing the humble pie. Featured relentlessly in the media when MicroStrategy was on top of the world, Saylor had all the accoutrements of a mogul: he talked about running for president, he is said to have dated Queen Noor, and he rented out FedEx Stadium in Washington, D.C., for a Super Bowl party. He was also prone to bold, evangelical pronouncements, such as: “I’m on a mission from God, and if you don’t buy from me, we’re all going to hell. I mean that literally.” Now, not to put too fine a point on it, those words are coming back to haunt him. “What’s pretty clear right now is that during 1999,1, along with a lot of people in the tech business, sort of lost control of our media identities, or lost control of our identities,” Saylor says. “The result is, when things are good, the market is just in love with ‘What’s the new sweater you bought?’ and ‘What kind of bicycle are you going to ride?’ and that becomes a big thing, and, of course, then all those photos and all those images, they stick with you. And when the market turns down, those are fairly easy sources of ridicule.” He can’t help but think of James Carter, the young hurdler in the 2000 Olympics who, when he realized he was creaming his opponents, turned around and waved— “a sort of youthful, exuberant thing,” remembers Saylor. “And I thought to myself—actually I cringed, because I realized: he had lost control of his media image at that point, because no matter what he does for the rest of his life, if he loses in the semifinals or the finals, they’ll play that image.... In my particular case, a year before, I would not have recognized why that was a mistake.”

It’s difficult to start getting misty-eyed for Saylor, who may only get to play around with a piddling nest egg of around $1 billion. After all, does anyone actually believe that MicroStrategy was worth what the market once said it was worth? Certainly, the ones who have the least sympathy to offer the Mike Saylors of this world are the young people whose options are worthless. Scratch the surface of their disillusion and you’ll get to the rage. To observe the vitriol uncensored, one need look no further than fuckedcompany.com, an unsettling forum for anonymous disgruntled dot-commers, in which “These fucks accomplished their goal—an I.PO. and dumping their fraudulent shares” is a typical example of sharing.

“The people left holding the bag are all the young employees,” says Namakajo, who believes the worker bees were flat out sacrificed. In many cases, he claims, the top executives knew all along that their companies were failing and did whatever they needed to do to line their own pockets, while keeping the truth from their employees. First, there is the socalled “Friends and Family” catch. This allows a C.E.O. whose options are tied up for a certain period to have his inner circle cash in and out immediately, helping to steer what one calls “the great I.P.O. swindle.” Second, Namakajo explains, are the bountiful stipulations written into the executive contracts, which he himself was responsible for putting together. “I’m the guy who writes the deals that protect the C.E.O.,” says Namakajo. “When a company goes under, you can’t sue him.... You can’t take his assets; he gets to leave with his laptop, he gets to leave with his car that the company bought.” Referring to a senior executive at the now bankrupt U.B.O., Namakajo says, “She basically left the company because it was shit on a stick, right? Awful place to work. I put in her contract that she gets paid for a year after she’s gone. So it’s, like, the company may be going out of business, it may be laying people off, but she got a check. There’s people at U.B.O. now that are still getting paid. I’m not lying to you. They’re still getting paid.”

Companies that once eagerly courted the press are now I ducking reporters’ phone calls. A spokesman for Priceline said no to an interview, explaining, “We don’t have anything to say. We’re just down here working hard, moving forward.” This, despite the fact that Priceline’s stock has fallen from $162 a share to around $3; that the company is facing 21 classaction lawsuits; and that even spokesman William Shatner has beamed out, owing to his drastically devalued options.

A few former prospectors even admit they’re relieved. “It ended the whole nightmare, in this fake world, creating this fake media thing,” says Andy Wang. “It’s sort of like a grandmother on life support. You’ve already made peace with the fact that this isn’t going to last.” For Mike Saylor, it’s almost a welcome slap in the face. “The market is sending us a message,” he says. “It wants us to put our heads down and get back to work, and take a much more humble approach to our business, and take a much more humble approach to our personal lives.” Strangely enough, that rationalization may have even permeated the parallel universe of wild man Josh Harris. When asked about the last days at Pseudo, Harris says, after some thought, “I’ve had to wonder to myself fairly recently whether I’ve been in denial.” Living in front of 32 cameras might have little to offer the rest of us. For Harris, it may be bringing him closer to reality.

Whafs pretty clear right now is that during 1999, I, along with a lot of people in the tech usiness,.... lost control of our identities."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now