Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowRich, Jaded, and Lost in L.A.

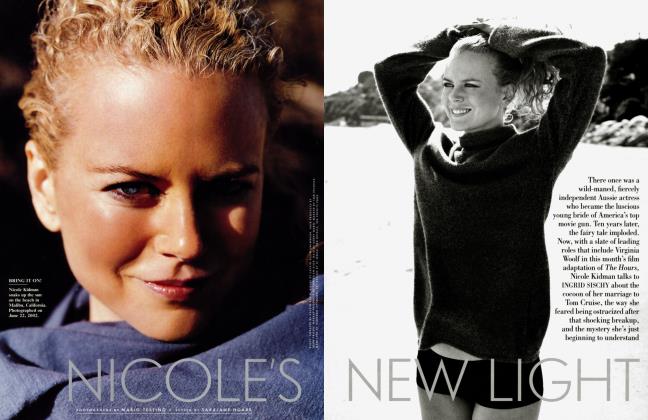

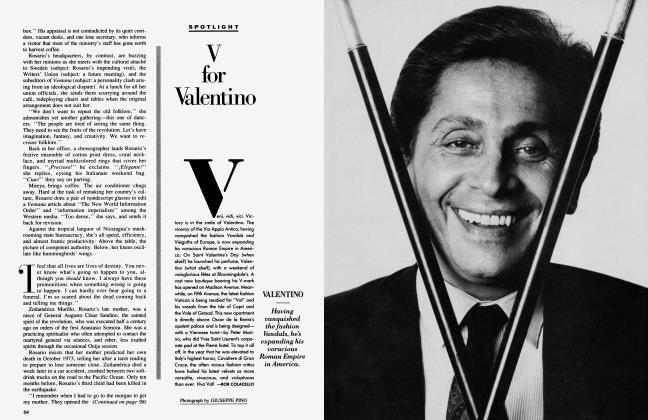

Raised in the golden playground of Beverly Hills, Matt and Mare and Kelly are home from college for vacation, flush with their parents' cash, and exploring the big questions: Should Marc aim for producer or executive producer? Should Kelly do a bikini spread for a men's magazine? Will Matt go to law school or find an agent? And what about 9/11, war, and poverty? Riding shotgun as the trio cruises L.A. (Mr. Chow's, Fred Segal, the Mondrian, etc.), NANCY JO SALES watches them test the limits of love, friendship, and getting into the latest club

NANCY JO SALES

FOR DETAILS, SEE CREDITS PAGE

"Living your life like youre trapped in a bad rap video is just not that appealing'

He was a good-looking boy in a town full of stars, where somebody was always trying to tell him he "looked like someone." He had gone away to college and dropped a few pounds, taken up yoga, was getting tips from the hairstylist for the pop singer Shakira. His previous weight and his seriousness—a tendency to talk philosophy in a place where the favorite subjects were spa treatments, success, and shopping—had earned him the nickname Baloney in high school. His name was Matt Bilinsky. But now that he'd come home for the summer looking so favorably transformed, his friends had changed his name to Ballonius, which didn't make him any too happy.

He was standing outside a new nightclub on Wilcox called Nacional when the limo pulled up, carrying his two buddies and their dates for the evening. They all tumbled out, looking sated after having dined on heaping plates of Asian fusion at Mr. Chow's, where Jon Lovitz, David Spade, Michelle Phillips— "Bijou's mom"—and "the girl with the whipped-cream bikini in American Pie" had been sitting at nearby tables.

"Spade," said Marc Protzel, one of the boys. "Stay in L.A. for a week and you'll run into Spade. Him or Coolio."

"I talked to Jon Lovitz outside smoking a cigarette," said Evan Glucoff, the other boy. "He has a funny voice. We needed a lighter."

They filed up to the door of the club—a new place popular with a young Hollywood crowd—behind Kelly Terry, Marc's still-platonic summer romance. She was 19 years old, that very day, and a blonde to make a Beach Boy bust a surfboard in two, as light and bubbly as the froth on a wave.

"O.K., I'm gonna let you in," said the bouncer, glancing from her face to her ID to the little white Prada shoes she had bought that day, "but I just want you to know I know this is a fake."

"Oh," said Kelly, passably sheepish, "O.K." She'd been going out clubbing since she was 14 and had never been denied access anywhere.

"It's her birthday, man," Marc said after they'd all settled into a booth in the dark, booming lounge upstairs. The place was filled with blondes dressed like Britney Spears, and had a large, unisex bathroom with a lot of people leaning over little white lines of high-spiritedness.

"Happy birthday," said Matt in a voice that lent an air of tragedy to the simplest phrases, staring a little too long at the girl.

Someone commented on all the "faux-hawks"—that summer's hairdo for young men, a mini-Mohawk fashioned with "products."

"It's not anarchistic Mohawk, it's runway Mohawk," Kelly complained.

"It's a conformist Mohawk," said Matt.

Kelly laughed.

They ordered an expensive bottle of champagne and attempted to have a good time, as all indications said they should. But although the club was packed, there was a curiously dead feeling in the air—like a party that was over but someone had forgotten to turn the lights on to inform the guests.

Matt got up and went over to the bar. "There are 300,000 rice farmers in China who couldn't give a rat's ass who's in this club right now," he said, "and you got two dudes downstairs whose worlds are ruined because they didn't get in."

Apparently, he had something on his mind.

"Look around you, look at all these nice, good-looking young wealthy people," he said. "Look at this fucking town. Look at the cars these people drive, man. Everyone's putting on a front. Everyone's got such a fucking agenda. It's hard to find just, believe it or not, normal people—"

A couple of studio-executive types were rapping along loudly to Eminem.

"Here's something I feel pretty sad saying about myself," Matt said. "I have a little trouble being in New York, you know why? 'Cause real people are forced upon you there, and you know what real people do to me? They depress me." He looked a little stricken by that.

CONTINUED ON PAGE 356

CONTINUED FROM PAGE 341

He said something had happened to him since he'd come back from school—Comelisomething he was trying to figure out.

"The first night I got in," he said, "I got a call from my friend, and he was like, 'Yo, this other dude just got his rims on his new Mercedes,' and we rush over to go see his rims. And then my two friends were looking at this car going, 'Oh, yeah, your rims are so tight,' 'Oh, I'm so happy.' And I'm going, What the fuck is going on here?—like I don't understand. And it wasn't even like I could say, What's the big deal?, 'cause I couldn't even understand what the hell was going on. "

Kelly popped up, looking curious and amused. "Isn't Matt great? Isn't he a funny kid?" she said.

He put his arm around her, staring off dramatically, as if for a photograph.

It was Marc who'd found Kelly at the University of Colorado at Boulder, where he was a junior and she'd just finished her freshman year. She'd already determined she was not going back. "The people were really country," she said.

She had the L.A. accent, perpetually casual and bored. "They were all, like, crashing beer cans against their foreheads. And it was like, Where the fuck did I drop myself off?" she said. "My roommate was from Oregon. Her past included basically, like, going out in a little dinghy with a six-pack."

Kelly had grown up in Beverly Hills, which she seemed to see as a kind of beautiful disease. "You're surrounded by people with just extraordinary wealth, and everybody has the same background," she said, "and so your experience is very narrow. Importance is placed on things that are not terribly important, such as money."

She comes from an old L.A. family. She said her first words were "Bullshit, Daddy."

"People who have money really like to demonstrate their wealth. There's no discretion here," she said. "It's really hard to form your own identity when your identity is made up of what clothes you wear and where you like to go."

In high school she had partied at the Playboy Mansion and with P. Diddy in the Hamptons and Miami. "Puffy really knows how to throw a party, he's the showiest," she said, then laughed. "I'm dissing Puffy, I'm gonna get shot."

She had graduated from Crossroads, an L.A. private school, and says Meg Ryan and Dennis Quaid's son and Maria Shriver and Arnold Schwarzenegger's kids went there. The boys wore Armani and Gucci to the prom; Kelly had worn a Roberto Cavalli gown. "It's, like, glamorous," she said.

"Girls check out girls' clothes," she said, "girls know how much your outfit is, because we all shop at Ron Herman's"—the emporium of cool better known as Fred Segal.

When the limo had passed by the store on the way to the nightclub earlier that night, she cheered.

"But, I mean, I love L.A.," Kelly said.

And she found she couldn't leave.

Now they were on their way to the next party, a "random house party up in the hills."

It was Matt, Kelly, Marc, Evan, and Daniella Segal, a pretty, dark-haired girl from New York who was visiting for the weekend.

They started talking about the world.

"Everybody hates us," Kelly said.

"I think we come across like overindulgent idiots," Daniella said. "Americans aren't respected anywhere, really. Like, other countries have things that they're known for and are great—like Russia and space?"

The limo driver and Evan, who knew the address, started muddling through the interminable directions that characterize a typical outing in L.A.

"Would someone please explain Mulholland Drive to me?" Matt said.

"Saturday night's all about spontanooity," said Marc.

"Spontaneity," Kelly corrected him, with a laugh.

Marc—who looked like Adam Sandler doing Dustin Hoffman in The Graduate—appeared to kick himself mentally, then throw himself down a flight of stairs. He'd been wooing Kelly all summer, and said his friends had "ripped him a new asshole for not sleeping with this girl."

The summer night was cool and the windows were down; the winding roads were dark and the mansions were still. Jay-Z was rapping softly about how he'd come from the ghetto and hustled coke and become a rap star and now owned a Bentley.

"Things are not what they seem in L.A.," Kelly said confidentially, off to one side. "It's a very reputation-conscious city. That's the reason why people in private schools learn self-preservation, because people love to run their mouth about you. Like, I can't tell you the shit that's been said about me. Like, people said I was a coke whore. I had never done any of that stuff—I hadn't, well, at that point.

"That's why you have to go to, like, Europe," she said. "Like, I saw there real people who have noble professions. People who don't have a lot of money but are completely content with the way they look."

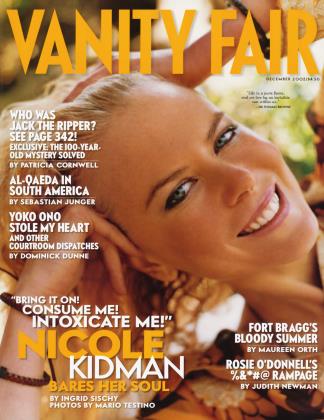

She looked like a fallen angel in designer wings. She had recently been asked to do a bikini shoot for Maxim magazine, which she'd agreed to, although she said she knew it was "really skeevy."

"You know, I mean, circumstances of birth ..." She let the phrase hover like neon. "I don't know, I think it's terrible to judge somebody by a circumstance, and that's what people do here. Like, when you're bom into a wealthy family, or when you're bom attractive, or, like, you have social skills, people will rip you a new one, because they don't want you to get ahead of them."

The party was eerie—a few college boys smoking joints and drinking beer by the pool at a high, glass house that was all Mondrian angles and colors, lighted low.

"It's my house. It's worth three million. I came into some money," said an intense boy who, Daniella later said, "had the eyes of a rapist." "Don't take anything from the refrigerator," he told them.

"Nice house," "Nice house," they all said, padding slowly up and down the levels. There didn't seem to be any personal effects anywhere.

"That was not his house," "No way that was his house," they all said outside, as they were leaving.

"Everything is fake here," Matt said, by way of explanation. "Accounting courtesy of Arthur Andersen."

Back in the limo, Evan—a slick boy with skin so smooth it looked like the work of a facialist—said, "Breast implants are considered trashy now."

"Everyone gets nose jobs," said Daniella.

"Nose jobs are different, but I know a girl who got breast implants and she got clowned," said Evan.

"\bu're at a party and you're in the Jacuzzi and somebody's breasts will float," said Kelly with a little shudder.

In the driveway of Evan's house—it was now around two a.m.—Kelly jumped on Matt's back. He carried her around. They looked like a pair of lovers in a perfume commercial.

Marc frowned.

He said he didn't know exactly how he felt about her, but it was becoming an uncomfortable thing: what was happening between him and Kelly. They'd been inseparable all summer, ever since they'd come back from Boulder. He said he'd been falling for her ever since they met, on the way to a Roots concert with a bunch of other L.A. kids at the University of Colorado. "But she knows I'm not one of those guys who's gonna be like, 'Hey, Kelly, let's get freaky.'"

He said she called him 8, 10 times a day. "It's a very odd relationship because we really do function at times as a couple. But we're not," he said. "At some point I'm gonna have to decide what I'm gonna do, if I'm gonna go in really hard for her."

Kelly squealed. Matt was swinging her around.

Upstairs in Evan's house, The Crocodile Hunter, a nature show, was playing. James Bond (Sean Connery) was cocking an eyebrow on the wall. Evan lived in the guest cottage; his parents lived in the main house, a lovely, tiled Spanish thing with a backyard the size of a small theme park.

Matt and Kelly had disappeared somewhere. Evan and Marc were sitting on Evan's terrace, smoking, with Daniella.

"You're in such a gray area when you're 20," Marc was saying. "All my girlfriends from L.A. are into older guys."

He lowered his voice. "Kelly, for instance. Kelly loves me. She thinks I'm the fuckin' man. But the problem is, I'm too young for her."

"Shhh, shhh," said Evan.

Kelly came out, looking buoyant, blue eyes round.

"We're talking about girls' dating older guys. She's a fan," Marc said flatly.

"Oooh, yeah, I'm a fan," Kelly said, coolly sarcastic. She didn't seem to like him talking about her. "No," she said smoothly, "the thing about an older guy is that they, like, have seen more and there's a little bit of a learning curve."

"We're 20 years old, we're mature guys," said Marc.

"I know you are," she said, "but there's something about guys that have gone through college and that have jobs and have a little life experience."

She'd been dating an entertainment lawyer who was 27.

"Why do you want that right now? You're not going to marry him!" Marc said.

Evan laughed.

"I think it's an instinctive thing," Kelly said. "Because, well, I'm a little too practical to just fall in love with somebody because— uhhhh—I'm in love with him." Now she was torturing Marc. "Like, to marry somebody because I'm in love with him? Like, I'd never marry someone who I thought couldn't take care of me in the way that I—you knowhave been brought up. Do you know what I mean?" She sniffed.

There was a silence.

Marc tried to stay respectful. "That's a big struggle," he said.

"You know what it is?" Evan said. "It's basic anthropology. Girls want men who can take care of the family."

"They say guys are 10 years behind girls," said Kelly.

Matt appeared on the terrace, glowering. "Yeah, right."

"I don't believe it, necessarily," Kelly said, venturing, "this is exactly how I feel about guys your age and stuff—"

Marc scoffed. "Your age?"

"Well, guys my age," she said, "are playing adult with their parents' money. Well, that's what my friends do."

Another little silence. Something hitting home.

"I don't like the feeling," Matt said finally.

"They totally play like grown-ups with money that's not theirs," Kelly said.

"I've made money in my life!" said Marc.

"I make, like, 200 bucks a week," Evan said—he was a U.C.L.A. student, interning at MGM Studios and a law firm that summer—"but I live like I make a lot more."

"Guilt, guilt, it's so worthless," said Matt.

"I have a really hard time reconciling Gucci and poverty," Kelly said. "It's, like, white woman's burden."

"Guilt is a worthless thing, and the burden is a metaphysical fuckin' nightmare," Matt exploded, in full Ballonius mode. "You have so many goddamn people you can look at and feel guilty for. I can feel guilty that that dude's driving the car tonight—"

The limo driver—a jolly, pear-shaped man with a scruffy goatee—was relaxing down in the street, listening to classic rock.

"I can feel guilty that there's some bum out in the park," said Matt. "I can feel guilty that there's a Guatemalan kid waking up at five in the morning to make hats 15 hours a day. There's so many fuckin' people, it's a never-ending cycle."

Kelly was nodding. "You know what actually helped me through the white woman's burden," she said, "was Ayn Rand's Atlas Shrugged."

"You like Ayn Rand?" Marc said, aghast.

"The virtues of selfishness, man." Matt smiled acidly.

"I love Ayn Rand," Kelly said. "Well, I mean, you need certain people to keep the economy going."

Fred Segal, which has two locations, one on Melrose and one in Santa Monica, is not only a store but a quasi-religious institution. Kelly said that, no matter how blue she felt, a trip there was sure to raise her spirits, "no matter how fucking shallow that sounds."

The parking lot of Fred Segal is always full of Porsches, Jaguars, and shiny S.U.V.'s. Inside, you can buy a child's T-shirt by Roberto Cavalli for $144. A JESUS IS MY HOMEBOY T-shirt is only $40. In addition to the usual Prada and Gucci, the store carries a preponderance of young designers close to Kelly, Marc, and Matt's age and social disposition, which Kelly said she thought was "really supportive."

"You know Fred Segal," explained a boy I met in L.A., "the place where the rich girls buy their clothes from the rich girls." Marc's sister, Pam, has a clothing line there called Ella Moss. (Marc said, "She never returns my calls.")

A clerk there said that, after al-Qaeda brought the World Trade Center down and

George W. Bush urged Americans to shop, a frequent customer said she "felt like Rosie the Riveter," and was going on from there to give blood.

On a Sunday evening in Beverly Hills, met a friend named Jonathan Caren at the Backstage Cafe, a little sidewalk bar. Matt had been seeking out Jonathan a lot lately for advice. He, too, had come back from school (he went to Vassar) that summer feeling changed, along with the world.

"Our lives are a parody and we know it," Jonathan said. "Some kids don't reconcile it and they buy into it and they live it. It's addictive and they're stuck in it and there's no way out—going out every night, drugs, girls."

"Here's the sad part," Matt grumbled. "It's not that fun."

"My theory is kids reflect what they see from adults and parents," Jonathan said. "It's amazing how far you can get, deep into it, and how much you can hurt yourself—ruin yourself—and not even recognize that that's what you are doing."

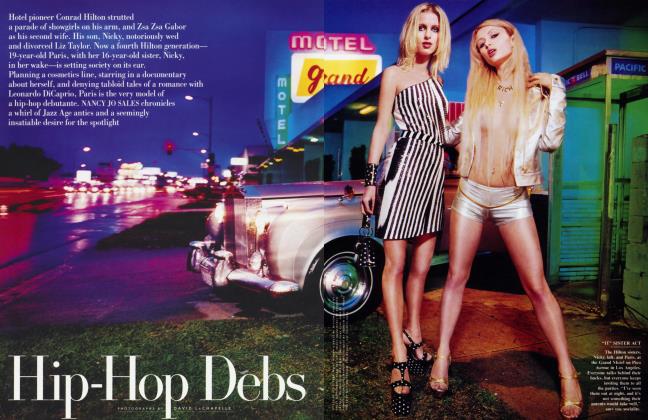

They started talking about Paris Hilton.

Matt said he had been sitting with his family eating seared salmon at Wolfgang Puck recently, "and I thought, What if some guy in a Palestinian refugee camp could see us now? But then I thought, What the fuck can I do about it?"

"You have to take care of yourself first," Jonathan said earnestly.

That summer he had become Dr. Phil to his friends. In high school he'd done the club scene, too, was even captain of the football team. "Jonathan was Mr. Beverly Hills High School," Marc had said earlier. "He was always Mr. Fashionable on a Saturday night."

"I couldn't be that thing anymore," Jonathan said. "I can't go back. I chose a different path"—to be a playwright—"which may mean that I never achieve the kind of financial success that has surrounded me growing up, and that scares me, but I know this is what I want."

He was wearing a T-shirt that said, THANK GOD I'M NORWEGIAN. He'd let his hair grow out wild, so that his friends said he "looked like Barry Gibb."

He was staging a play in L.A. that summer—an indictment of Starbucks based on the Oedipus myth—entitled Brew Bucks. It featured a character in a rat costume, which Jonathan sometimes wore outside of rehearsals.

"But you don't even know where to take a stand," he said. "Kids mock themselves by becoming political—it turns trendy."

"Is our whole American thing just over?" asked Matt.

It was too much to contemplate. They started talking about Marc and Kelly.

"Is he into her, or the image?" Jonathan asked.

"Half of him wants to stay Marc," Matt said, "and half of him wants to be a big Hollywood mogul like Don Simpson and bang lots of women."

A sunny day in L.A., as usual. Marc was spinning along Sunset in the new "graphite pearl" Lexus IS300 he'd gotten for his 20th birthday. It was outfitted with Global Positioning System, where you punch in a destination and a computerized voice tells you where to turn.

"It's the same stuff they drop the bombs with," Marc said cheerfully.

"Left turn ahead," said his car.

He turned.

Up the road, Austin Powers was cavorting happily on a 30-foot billboard.

Marc started talking about how he wanted to be a movie producer.

"My big transitional phase is, should I be a producer or should I be an executive producer?" He laughed.

"A lot of people around here want to be in the business," he said offhandedly. "It's what you see on a daily basis. I grew up with the notion that, if I want to make a lot of money when I get older, I gotta be in Hollywood, and so that's sort of the direction I put myself in."

"Thank you," said his car.

"You can do some really cool stuff, making a good movie. That's cool, that's fun, I wouldn't mind doing that. But it's a paranoid industry."

In high school, he'd been an intern at George Clooney's production company, Section Eight. "George's whole thing is, like, 'I'm the cool celebrity, I'm nice to everybody, I'll talk to the third set painter.' I would always joke with him, 'We're gonna play golf, George.' "

Marc's cell phone rang. It was Kelly.

"O.K., so get the poncho," he told her.

He clicked off. "She's dependent on me."

He zoomed along, thinking. "If I don't make it," he said, "it's gonna be a miserable life."

Julia Roberts appeared on a billboard, hands in prayer.

He stopped for a steak sandwich at Jones's, a lunch place favored by movie producers, and started talking about how "girls out here don't know how to eat—like, breakfast, lunch, dinner, they don't know what that is. Like, a girl I know, she'll go all day without eating, and then she'll just stuff herself and that'll be it. I don't think she's bulimic. It wouldn't surprise me. She has a bony ass ... "

He started talking about Kelly again. She called him several more times as he had lunch. "Every night she asks me so many times, How do I look, how do I look?" He shook his head at the inconceivable.

"Kelly needs to know that she's so much better than she perceives herself to be. I don't think she's shallow at all," he said. "Like when people tell her she's gorgeous or good-looking, she just, like, gets so down on herself. It's so sad. She has a really tough time handling adulation.

"Like, she's gonna go do that magazine"— Maxim—"and do a whole bikini spread and she's ... I wouldn't say terrified, but she thinks it's the worst thing ever. She thinks it's horrible. Of course she'll do it, but she said to me, 'I hate everything that stands for.' I couldn't even comprehend what she was trying to say.

"I want to help Kelly," Marc said.

His cell phone rang; Kelly again.

She wanted him to go test-drive BMWs with her.

The woman known only as Jennifer eyed the kids collected outside Joseph's Cafe, a lounge on Ivar, like the Great Santini inspecting a sorry shipment of recruits. A woman in her 30s, she worked the door for Brent Bolthouse Productions, the reigning party promoters in L.A. She was never very friendly to civilians.

"She was definitely unpopular in high school," Marc said as he, Matt, Evan, and Evan's steady girlfriend, Andrea, finally made it inside.

"This is just a restaurant, " Evan pointed out.

The space was crammed with Reagan-era babies in Gucci fishing hats and strategically ripped vintage T-shirts. A couple of girls from Marc and Matt's high school came up to the boys and pinched their asses.

"That's how girls act now," Marc said, aside. "They, like, beg you to have sex with them—it's so weird."

A couple of other boys nearby were deep in conversation. "Dude, my face is so dry," one said, patting his cheek.

"Dude, it might be the micro-beads in your facial wash. It's too exfoliating," said his friend.

"It's just a bunch of pretentious whores and bastards gathered together to talk to other pretentious whores and bastards," said a wiry boy named Dave Eitches.

He was a friend of Marc and Matt's from Beverly Hills High. He said he'd come there that night in a chauffeured car so "we don't have to worry about the D.U.I." He said he was worried and peeved about President Bush's talk of invading Iraq, which had just started heating up that summer.

"He's brainwashing everyone's brains to think that we're the shit when—O.K., we might be the shit, but we're too cocky and we're too naive to realize that there's a whole world out there and the world doesn't revolve around America," he said.

He said he wanted to be an international film distributor.

"I'm into the money," he said, shrugging. "I understand what I stand for and I understand that it's a good thing ... but I can't make money off it."

Twenty songs later, Marc wanted to go, but Matt was hitting on a U.C.L.A. med student with a little black purse. "Aw, look, he's got the Perma-Flex," Marc said.

Matt had his arms folded and mashed up against his chest, making his newly developed biceps highly apparent.

"The sad thing is, girls, they want the guy in black. Look," Marc said, nodding to a table across the room where a large, balding man in a black-on-black suit was surrounded by a banquette full of accommodatinglooking young things.

"He's a music producer," Marc said wryly. "He does Korn. But, really, these girls want me, Evan, and Matt—they just don't know it yet. They'll learn the hard way."

Matt and Evan watched as Pamela Anderson pranced up and down the long, marble sushi bar in the lobby of the Mondrian Hotel, singing breathily, "It's been a hard day's night, and I been working like a daw-aw-awg."

She was a mini Jayne Mansfield in lowslung jeans; her bubble breasts jiggled as she shimmied and bumped against a tall, modelly girlfriend dancing next to her. Some tourists appeared instantly and took pictures.

"What is she doing?" Evan murmured.

"Whatever she can get away with," Matt said.

They headed toward the hotel restaurant, Asia de Cuba. It was another night on the town. They were meeting Marc and Kelly for dinner.

"My acting coach is hot," Kelly said, smiling brightly in the candlelight of a white leather booth. She'd had an acting class that day at the Joanne Baron/D. W. Brown Studio, where, "like, Benicio del Toro was there talking to kids. She coaches, like, Halle Berry."

"I just don't want you to wind up like Dorothy Stratten," Matt said.

"Like, dead?" Kelly giggled. Nothing could destroy her gaiety.

"We did repetitions yesterday," she said of her class. "It's three times a week. It's kind of intense, but I need something to be regimented and structured in my life. I'm always so exhausted, 'cause I'm always going out."

She looked as fresh as California produce.

"She looks like the Noxzema girl. It makes me feel clean just looking at her," Ballonius blurted out.

"Shut up, Matt," Marc said.

Kelly laughed.

They ordered plates and plates of AsianCuban and a whole lot of mojitos. The restaurant reached a thundering pitch.

Kelly returned to a favorite theme, how she preferred hanging out with older men. "But I wonder if, when I'm 27, I'll want to hang out with someone who's 19," she mused.

I asked her why she hung out with Marc.

"I pay her," Marc said.

"He pays me," Kelly repeated. "Um, he's just a really nice guy, and I was saying to him today, he can't come to terms with the fact that he's just really nice. And it's kind of endearing because he wants to be this idiot Hollywood asshole—"

"No, that's not true," Marc said.

"He wants to know that he can go and inspire fear in people," Kelly teased. "That's a big Hollywood thing. He always uses the term 'Hollywood sleazebag.'"

"Like Ovitz," Matt said.

Kelly wrinkled her nose. "Oh, don't say that." Mike Ovitz's daughter was her best friend.

"I don't want to be a sleazebag," said Marc. "But the bottom line is I'm not the nicest guy in the world—"

"Yes, you are," Kelly said sweetly, although it didn't sound exactly like a compliment.

Marc insisted, "I've done some pretty shitty, stupid things in my day. But when it comes down to it, I am a nice guy and I might have some trouble dealing with that because I live in a world and I live in a town, especially, where—"

"You get ahead by being an asshole," said Kelly.

"I mean, I think I have the ability to go both ways on that," Marc said. "There's a saying, 'Nice guys finish last,' and I don't want to finish last."

"He can have a good time doing anything," Kelly said, sounding almost like a girlfriend. "I think it's fun to go out and stuff, but when your life starts to resemble a bad rap video—you know what I mean? Living your life like you're trapped in a bad rap video is just not that appealing. So, like, Marc, he's the kind of guy you can go out with, or you can just chill with."

She smiled at him.

He smiled at her.

"Are you guys together or no?" asked Andrea, Evan's girlfriend; she had joined the table.

Kelly made a face. "No, no, no, no," she said.

Andrea apologized. "I'm an outsider, I'm meeting all these people for the first time—"

"We get along," Marc said.

Kelly winced. "It's weird to talk about your friendship with somebody, but I will give it to him—I tell him a lot of stuff I wouldn't tell a lot of my guy friends, and I feel bad because he is so nice and he is so easy to talk to because it's almost like I almost feel bad like I'll tell him stuff—"

Marc purred at her, "You're all over the place."

"I'm a little nuts," she said, "and he's, just, very nice, and he's, you know, if I ever want an honest opinion about something, I know I can go to him and he'll give it to me straight, but I'm sure he'd like me to spare him—"

"Spare me?" said Marc gently. "Why? You're saying good stuff."

"I mean spare you the details," Kelly said. She meant about her love life.

"I like Kelly 'cause she's different," Marc said. "She's cool, she's like the first girl I can go out and get drunk with. We kind of caught each other in the middle of a nasty winter in Colorado—"

"It really makes you appreciate growing up here," Kelly said. "In L.A., I was so live-for-the-moment. I was so party-girl. I couldn't see beyond what I was doing on any given weekend."

They started talking about America.

"Here's my thing," Kelly said, charged. "There's no time to be an idiot teenager anymore. I think all this has helped a lot of people to grow up really quick. There's a time for partying and there's a time for being real, and it's time to wise up and realize that. Like, there's no time to focus on the new, like, Balenciaga bag when—I mean, obviously, I like that stuff—"

"It's time to start doing something!" Marc said.

"You know what?" she said. "There's no glory, there's no honor, in being a kid that gets into clubs."

Marc looked at her with love and wailed, "I'm tired of this!"

"If I can just change my thinking," she said, "and realize that there's more to life than maybe what I thought there was, like going out to clubs, like the end-all-be-all of life was getting hit on by Mark Wahlberg, being seen at this place or that place ..."

After dinner nearly everybody else went to the Kibbitz Room, a deli by day, bar by night, in the Jewish section of town.

Kelly refused to go.

"Kibbitz is way too low-maintenance," she said.

A few days later, at a bright, fancy gym ilon Wilshire, Matt was laying out his mat. He was preparing for his yoga class.

"Power, and control," he said.

He was practicing his breathing.

"It makes me feel powerful, like I have control," he said.

He took his shirt off. His body was cut.

"I feel so powerful. It comes from here"— he pointed to his six-pack abs—"not from here"—his head.

"Once you know that ... " He let his voice trail off, as if the answer were selfevident to the initiated.

At the Cafe des Artistes, an airy French restaurant on McCadden, Kelly was sitting alone drinking tea one warm afternoon. She was wearing a pair of Gucci sunglasses she said her father called her "Fuck Off glasses." "My dad's like, Wanna take those off and have a conversation with me?" She removed them.

She said that she was having her doubts about posing for Maxim, but that she was resigned to the inevitable march of opportunities coming her way. "It's one thing to be like, 'I don't buy into that,' and yet I'm going to be in a bikini shoot," she said.

"It's the money," she admitted. "Not that I'm, like, motivated by money, but when you don't have financial independence, people talk to you about how it's not your money all the time, like I've had. Like, I don't usually pay for my dinners. That sounds like such a ho comment, but you're always indebted in some way, you know? It makes people feel like they've bought a piece of you."

She said she was dating several different guys, but on the whole she found L.A. men a bit hard to take. "A lot of guys in L.A. talk about their cars when they're trying to woo you. They're like, 'Yeah, I'm Jim Carrey's manager.'" She smirked.

I asked her if she thought Marc was in love with her.

She nodded. "But I don't even understand, going out with, like, Kelly platonic friend, you know what I mean? I'm like, Take a girl out who will do you. The thing you have to realize as a girl is, do guys really want to be friends?" She said that Marc had taken her to meet people and asked her to pose as his girlfriend. "He made me the fucking girlfriend."

But, she said, whatever happened that summer seemed to pale in comparison with what was going on in the world. "It's weird growing up at such an unparalleled time in history. September 11, it was like, did I just go see a really horrible Jerry Bruckheimer movie?" she said.

And she said she understood some things about Osama bin Laden.

"Marc's like, 'He's one of us, he's one of us.'" Meaning Osama was a spoiled rich kid. "He's completely unhinged—that's why people need to hug their children. It's funny what jealousy will drive people to do, don't you think? He was upset because he didn't get his piece of the pie," she said.

The most Hollywood of all L.A. restaurants is probably the Ivy, where the front porch is never lacking for people in "the industry."

One evening, Kelly, Marc, Matt, and Todd Rosen, an arch boy with a faux-hawk, were having dinner before going to Moomba. A woman seated at the next table came over and asked Matt to light her cigarette.

"I'm sitting with the writers from Friends," she let drop, eyeing him. She was about 30, tall, bosomy, and rather nice-looking, in jeans.

"What do you do?" she asked.

"He's a model," Marc said.

"Oh, really?" she said, interested. "Um, I'll be back, I'll bring my wine over ... I'm Lil, by the way."

Matt's friends started snickering.

Matt confessed to them that he hadn't been with a girl "since March 21," although lately he'd been flooded with chances. A woman in front of Sushi Roku the other night had told him he "had a Marlon Brando-James Dean quality" and said she "would like to represent him."

"Oh, don't tell him that," Marc said, laughing.

Matt was studying for his L.S.A.T.'s, but meanwhile had asked Marc whether the woman's agency was "legitimate."

And then at the Sunset Room, another night, a girl they knew named Candace had made out with him in a comer—but then left with another guy.

"Maybe she remembered what you looked like in high school, Matt," Marc said.

Matt acknowledged, "I had a mullet for years because I didn't know any better."

Todd laughed. "He looked like Tonto in 1875."

"I know who the fuck I am!" Matt said.

"He's really, really good-looking," Kelly said, quoting a line from Zoolander, the Ben Stiller male-model comedy.

Marc said, "He almost made it with Tiffany," the 80s pop star turned Playboy novelty. "Vegas, New Year's Eve. We're leaving the Hard Rock Hotel. Me, Matt, and Evan had a limo that night. We had a couple of random girls with us, it's three o'clock in the morning. We're getting into the limo, going back to our hotel, when all of a sudden two random chicks just walk into the car. O.K., whatever, two girls, no problem, there's more room. So we're driving around when all of a sudden one of the girls with us goes"—high girl voice—"'It's Tiffany!'"

"And I'm drunk and I go, 'Who the fuck is Tiffany?' I felt really bad," said Matt.

"She was in our limo," Marc said. "So one of our girls starts singing, 'I think I'm alone now,' and Tiffany, you gotta understand, is gone, and she's like"—out-of-it Tiffany voice— "'Heeeeey.' Then her little caretaker buddy friend is like"—stern—"'Be discreet, be discreet,' and we're like, 'Who the fuck is Tiffany?' So we start just messin' with her, like 'Tiffany, can you sing?,' just totally being assholes. So we get to our hotel and, by the way, Matt is trying to hook up with her—"

"This is a lie," Matt said.

"Oh, no, he's trying to hook up with her little caretaker!" Marc laughed, remembering.

"What do you mean trying?" said Matt. "I was. Tiffany was throwing up in the garbage can."

Now they were all laughing, except him.

(Tiffany's manager said that Tiffany had not been in Las Vegas on New Year's Eve.)

Matt got up and went to the bar, not quite in a huff.

"In high school we used him to drive us everywhere," Todd said, not unaffectionately.

"He was just happy to get out," said Marc.

"He was happy to be out with the cool dudes—cooler than he was," Todd said. "Now he's ... I don't know what he is today, but"—Matt was on his way back to the table now—"his vocabulary is very extraordinary."

"He's ridiculously good-looking," said Kelly, drinking another gimlet.

Marc said, "He's the new-and-improved, pseudo-hipster, cool Matt."

"He's like"—deep Matt voice—"'I don't care what you say about me.' ... His butt is really nice," Todd said.

Matt snarled, "You wish."

"He's ridiculously good-looking," said Kelly in her Zoolander voice again.

Matt tried to change the subject. There'd been a lot of serious talk going on among his friends, and he tried to resume it, drawing a parallel between the U.S. and ancient Rome, using Gladiator as a metaphor.

"They asked him why did he fight for Rome," Matt said, in his deep, somber voice, "and he said, 'Because I've seen the rest of the world and that is the darkness and Rome is the light.' And I guess that's it—say what you want about us, but this is the light."

But nobody was in the mood, and they all started laughing at him again.

"Fuck 'em, whatever," Matt said. "I don't care about you two."

Kelly had gone to the ladies' room.

"We're pretty shallow people," Todd said.

Then Lil, the woman from the Friends table, came back.

"May I sit down?" she said.

She sat in Kelly's chair, crossing her legs, arranging her hair, and magically started talking about Matt's predominant obsession, the L.A. Lakers—or a Lakers party she had been to. "I didn't know anything about basketball," she said, "and I was like, This is the greatest party, who are these people?"

"Man, I'm so jealous," Matt said, smooth.

Marc and Todd sat back, watching, about to burst. The guy who used to drive them around town was now making time with a grown woman who had no idea that he went by Ballonius.

Then Kelly returned, and seeing someone in her chair, she wavered a moment, not knowing where to sit.

Eyeing Marc steadily, Matt slowly pulled Kelly to him and then onto his lap, as if it were the most natural thing, as if she were his girlfriend.

Matt stroked Kelly's hair as he continued talking casually to Lil. Marc stared. It seemed a payback for Marc taking shots at him.

Lil flushed, then made some excuse and got up and left, tripping over the iron chair.

Matt continued stroking Kelly's hair. If anything seemed to say he was different now, changed—more powerful and in control—it was this. He had Kelly on his lap.

Marc sat, fuming at him. "What are you doing?'1 he finally said.

Later, Marc and Kelly left. Matt said, "Whatever. I told him, from now on, when people ask, 'Are you dating her?,' just say, 'No, we're just friends.' Just decide. What do you want to be? Make a move."

I asked him if he minded losing Lil.

"I can only sleep with women who are extremely good-looking," he said.

On my God, Matt just hit on me so hard," Kelly said out on the street, by Marc's car.

"Matt is done!" Marc spat. "You don't understand—I created him! Two months ago he was calling me up saying, 'I have no life.' He's my Mr. Bigglesworth!"

He started his car.

"He's my Mr. Bigglesworth gone mad!"

"Gone crazy bad," said Kelly, enjoying it.

Marc turned up Eric Clapton singing "Cocaine" and sped off.

"I'm just gonna start calling him Baloney again," Marc said, furious. "That's all I'm gonna do."

Moomba, the patio bar on North Robertson, was filled with under-age rich kids they knew. And Andre Harrell, the former president of Bad Boy Entertainment, R Diddy's company, was there. Harrell was known for always being somewhere.

In the smoky room with the pool table downstairs—the "V.I.P. section"—Kelly looked around and grimaced. "Everyone I knew in high school is here," she said. "This place is Loserville. "

She went off, leaving Marc on a couch by himself.

"Oh my God, this is so weird for me, there's the guy I lost my virginity to," she whispered. "But this man can have anything he wants!" she suddenly shouted, wrapping her arms around a tall boy who'd gotten her attention by sticking her with a pool cue.

Evan and his girlfriend, Andrea, were in a comer, soulfully making out.

Two girls were offering to buy Matt a drink. He sauntered off between them, smiling.

"Come on, please, I can't take anymore of this," Marc begged Kelly. He wanted to take her away. It took an hour.

Out in the parking lot, there was a man selling long-stemmed roses.

Marc bought Kelly one and handed it to her, wordless.

She looked at him and tried to smile. But something in her smile said the rose embarrassed her, and he saw it.

At the end of the summer, Matt went back to Cornell. On his way there, he stopped in New York and we had dinner and he said he thought it had been a good summer. "I feel so powerful right now, I'm scared of it," he said. "It's almost like I have all the keys to life. The synapses are working."

Marc went back to the University of Colorado without Kelly, and for the first few days he missed her terribly. "She's smart," he said on the phone, "and she knows if we were to take it to another level and get even closer, she'll hurt me."

And then came the day Kelly was supposed to do Maxim.

She drove to Zuma Beach on the day of the shoot in her black Ford Explorer. She parked in the parking lot. She looked out at the sand, where the photographer and the stylists with the bathing suits were waiting. But then she left.

"I felt so wrong about it," she said on the phone. "I felt so horrible, pulling out, to show up and be like, Uhhhhhh. It was so badly timed. But when it came down to it, I asked myself, What do you want to be? And I realized what we choose and what we don't choose to do kind of helps define us."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now