Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

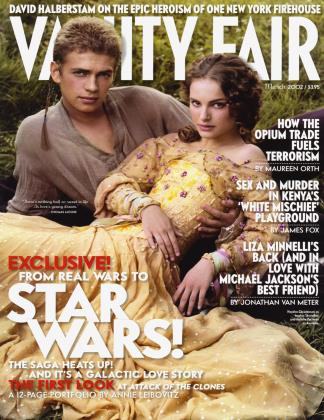

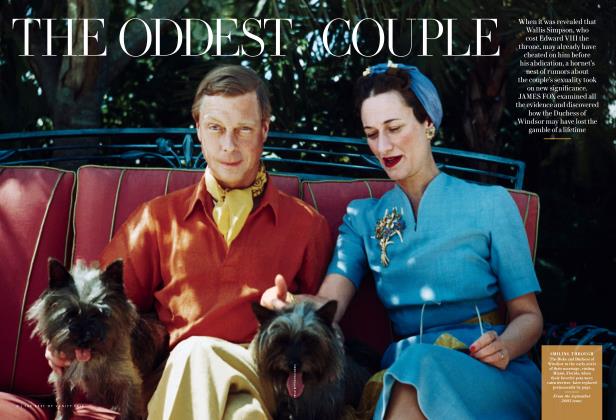

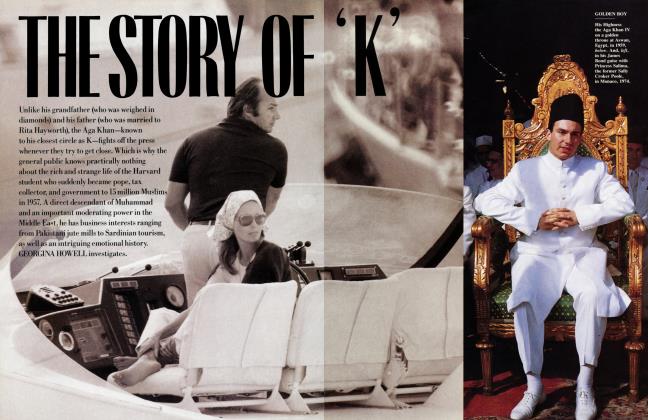

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowTonio Trzebinski’s murder last October in the gorgeous Nairobi suburb of Karen (named for Baroness Blixen) led the British press to make feverish comparisons to the 1941 slaying of Lord Erroll. After all, Trzebinski had been the charismatic and seemingly indestructible center of a hedonistic circle of writers and artists whose periodic descents on London were notable for their wildness. Returning to Kenya, JAMES FOX, author of White Mischief, the best-selling book on Erroll’s scandalous Happy Valley life and mysterious death, explores an explosive relationship, the police investigation, and Trzebinski’s dangerous playground. JONATHAN BECKER photographs the cast

March 2002 James FoxTonio Trzebinski’s murder last October in the gorgeous Nairobi suburb of Karen (named for Baroness Blixen) led the British press to make feverish comparisons to the 1941 slaying of Lord Erroll. After all, Trzebinski had been the charismatic and seemingly indestructible center of a hedonistic circle of writers and artists whose periodic descents on London were notable for their wildness. Returning to Kenya, JAMES FOX, author of White Mischief, the best-selling book on Erroll’s scandalous Happy Valley life and mysterious death, explores an explosive relationship, the police investigation, and Trzebinski’s dangerous playground. JONATHAN BECKER photographs the cast

March 2002 James FoxI remember Tonio Trzebinski as a six-year-old boy in 1966. I used to take him on my shoulder for walks in the Langata forest, with his brother and sister and his parents, who are still friends of mine. They lived in a dacha-like house in the woods in Karen, a suburb of Nairobi. We would go to the bleakly beautiful soda lake of Magadi, southwest of Nairobi, which was too hot after nine A.M. but magical at night, when you slithered between warm shallow pools under the stars. Magadi became one of Tonio’s treasured places in an African landscape he knew intimately. Not long before he was murdered, he had a family picnic there, shooting guinea fowl with his Masai companions.

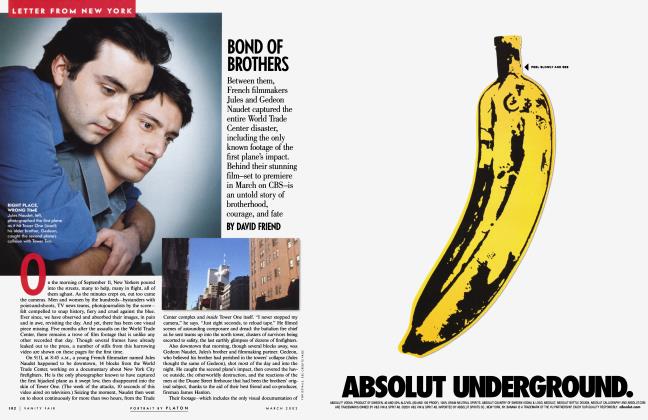

He was a reserved child when I knew him. Thirty years later he had grown into a man of powerful physique with an imposing personality and a public style that preceded him like a bow wave. Nobody could fail to notice his entrances into the bars he liked, such as the Groucho Club in London—with his booming voice, members of his fun squad in tow, his loud and roaring entertainments, and his spectacular consumption of vodka and the disco substances of the moment. He had become a successful artist. He had had a one-man show at the Lefevre Gallery in London in 1999; his paintings were selling for up to $25,000. In Nairobi in the 1990s, his close friends included a group of war correspondents who covered Somalia and Rwanda. Tonio was always the leader, the Capitano, as they called him. He and his wife, Anna, were fashionable to visit from New York or London, as, in earlier days, was their friend the photographer Peter Beard, whose tented roof could be seen from their garden. Francesca Marciano, a group member, wrote a novel loosely based on these self-mythologizing characters called Rules of the Wild. “Tonio was a kind of superstar in that world,” she said. “Physically he was like a Greek hero. He knew the bush, he knew the ocean; a superb fisherman and surfer. We used to spend Christmas together, go on safaris. He could fix a car, rebuild a road—nothing would ever stop him.”

In the mid-60s, when Tonio was growing up, Karen was not much changed from when its namesake, Karen Blixen, lived there in the 20s—her house had not yet been turned into a dire museum and a parking lot. It was the time of Jomo Kenyatta, the first president of Kenya; of the brief euphoria after independence. The houses had large gardens or acres of meadows enclosed with jacaranda and eucalyptus. Today, the residents of the KarenLangata area, black and white, fear the exposure of these same spaces and live in what one of Tonio’s bereaved friends called “perpetual fear”—in houses with iron gates, electric fences, dogs and guards, and panic buttons to summon the security firms that have replaced the police as the local guardians of law and order.

Tonio had built his wooden house and studio in Langata—a beautiful construction with verandas and pillars set on the edge of 150 acres of giraffe sanctuary below the Ngong Hills. There, on October 16 of last year, sometime after 8:30 P.M., he put his two children, Stas, aged nine, and Lana, eight, to bed and then drove his white Alfa Romeo to the house of Natasha Ilium Berg, a Danish huntress, writer, and model, a mile and a half away, at the end of a long dirt track leading off Bogoni Road.

His wife was at that moment at the Sierra Tucson in Arizona, taking a course in codependency. She had made this decision after the couple had had a spectacular—what seemed like a terminal—physical fight three weeks earlier, triggered by Tonio’s recent and secretive relationship with Berg.

Tonio’s visits to Natasha had become something of a routine, and when the watchman heard his car at about 9:10, he opened the large steel gates, but closed them again when the car stopped outside. There was a single gunshot, and a scream. Within four minutes a security van arrived with armed police inside it. They found Tonio lying a few feet behind his car, which was facing back toward the main road with the door open. He had been shot through the chest with a 9mm. pistol and had died instantly. A substantial amount of cash was still in his pocket, but his mobile phone was missing. The watchman had heard the grinding of gears and the revving of an engine—a failed attempt, it was presumed, to steal Tonio’s temperamental car. Tracks were found of another car speeding off. Tonio appeared to have turned his car around in a virtual cul-de-sac to escape his chasers.

Tonio and I exuded this energy’’ said Anna. It was a wild, fantastic time, no gray, the highest highs.”

"He could be impossible-a bully. Kenya does that to people."

Within the next 24 hours, as the news broke on Tonio’s family and friends, it also rippled through the white community. Nick Rabb, one of Tonio’s surfing companions, said, “It had such a huge effect on people’s lives because he was, as much as a human can be, indestructible. A bit like the Master of the Universe in The Bonfire of the Vanities.” Anna Trzebinski began the ordeal of a 24-hour journey back to Nairobi, asking that her children not be told until she arrived.

It was clearly not Tonio’s reputation as an artist that in the next two days attracted huge attention in Fleet Street. Rather, his murder had struck an old chord. BRITISH ARTIST IS SHOT DEAD IN KENYA—MURDER HASECHOES OF HAPPY VALLEY KILLING IN 1941, ran one headline, and another, KAREN MURDER RECALLS WHITE MISCHIEF DAYS.The Mail on Sunday went further: A BRUTAL SLAYING IN THE AFRICAN NIGHT, A LOVE AFFAIR WITH A WHITE HUNTRESS AND A FURIOUS ARISTOCRATIC WIFE. WELCOME TO HAPPYVALLEY ... 2001. White Mischief is a book of mine, published in 1982, about the murder of Lord Erroll, the assistant military secretary of Kenya, in 1941. It was later made into a film starring Greta Scacchi and Charles Dance. The links to Tonio Trzebinski were tenuous, even bizarre, but they were irresistible to London editors. Lord Erroll, the 22nd earl and a notorious womanizer, was killed in his car with a single bullet early one morning on the comer of the Karen and Ngong Roads, a mile or so from where Tonio met his death. I passed the spot almost every day on my recent visit there. Tonio’s mother, whose name by a confusing coincidence is Errol Trzebinski, had published her own book on the murder of Lord Erroll the previous year.

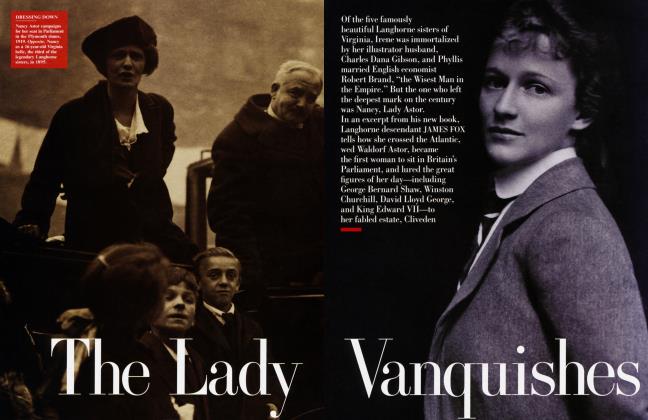

Lord Erroll had started an affair with Diana Broughton, the young wife of Sir Jock Delves Broughton, apparently with the resigned complicity of Broughton, who had only recently brought his new bride to Kenya. Broughton was tried and acquitted of Erroll’s murder, but the trial—with its parade of tropical selfindulgence—caused a scandal in England at the height of the Blitz. My book was a quest for the killer, and I felt certain that I had nailed the acquitted Broughton. But it also looked back on the world of the Wanjohi Valley in the Aberdares, the world of Happy Valley, which had scandalized settlers and metropolitans in the mid-1920s and seemed to do so again during the trial. Happy Valley originated with Erroll and Lady Idina Gordon, who later became his wife. I wrote:

Friends from England brought home tales of glorious entertainment in an exhilarating landscape surrounded by titled guests and many, many servants. In New rk and London a legend grew up [in the 1920s] of a set of socialites in the Aberdares whose existence was a permanent feast of dissipation and sensuous pleasure. Happy Valley was the byword for this way of life. Rumours circulated about endless orgies, of wife swapping, drinking, and stripping, often embellished in the heat of gossip. The Wanjohi river was said to run with cocktails and there was that joke, quickly worn to death by its own success: are you married or do you live in Kenya?

There was another coincidence. Anna Trzebinski’s stepfather, Michael CunninghamReid, was the stepson of Diana Broughton, the femme fatale in the White Mischief story, who later became Lady Delamere.

Along with Happy Valley, “White MischieF’ had become fixed in Fleet Street as the generic term for white misbehavior out of bounds in Africa. And now, exultantly, these factors could be banged together. Certainly the current group was living the life—culling zebras, surfing, catching marlin, partying all night, going on safaris at three hours’ notice. That one of them would come a cropper was surely inevitable, and a secret relief for readers in the gray London winter. The old “hideously hedonistic days,” wrote one columnist, “often ended in bloody tears. And it just has again.” The attitude was summarized in a satirical headline in The Spectator:MISCHIEVOUS WHITE TOFF MURDER IN AFRICAN PARADISE GROUP SEX. A photograph of Natasha Ilium Beig, the new scarlet woman, dressed in a revealing ball gown and posing between the tusks of a huge elephant, took up almost half of the front page of a section of The Sunday Times of London. Tonio, to match him with Lord Erroll, was portrayed elsewhere as a philanderer, which he wasn’t. Nor were any of the players aristocrats.

Among Tonio’s close friends were Aidan Hartley, who had worked for Reuters, and Julian Ozanne, former correspondent for the Financial Times in Nairobi Both professed outrage at the predictable reaction of Fleet Street to the murder, and then set about generating their own coverage. Hartley, while “trying to keep the press away from cruelly invading everybody’s lives,” wrote no fewer than four articles on Trzebinski for The Spectator, including one that began, “My mother and I drove by Happy Valley yesterday.... It is here that members of the 1930s White Mischief set are supposed to have held their orgies.” Anna Trzebinski gave at least three lengthy, biographical interviews, including my own, all arranged by Ozanne, to put the record straight and to downplay the “irrelevant” friendship with Natasha.

Much of the melodrama hardly needed embellishing. For the obsequies, a precedent had been set, almost a Kenyan version of a Viking burial. Three years earlier another wild and charismatic figure, Giles Thornton, a friend of the Trzebinskis’, had been shot in a house on the coast, protecting the servant from armed robbers. Thornton had been cremated with elaborate ritual on a funeral pyre near Mount Kenya.

Tonio Trzebinski’s body, adorned with mosquito netting, lay in state for three days in a tent at the bottom of the garden. His wife held his hand for hours, his daughter, Lana, stroked his hair, and a Buddhist monk chanted mantras. Anna said,

“Everyone felt the same: that he was so happy; that he’d plugged into the biggest nine[-point wave] he’d ever done and got that high he’d been looking for all his life.” He was then stitched by women into a shroud of Ugandan bark cloth. A funeral pyre of cedar posts was constructed above one of his favorite places in the Ngong Hills, with a view dropping down to the Great Rift Valley. Propped up on this pyramid were a surfboard, a crash helmet, and one of his paintings. Beneath it was his favorite meal, prepared by his cook—guinea fowl in Madagascar green-pepper sauce, mashed potatoes, a Mars bar, and a bottle of good Bordeaux.

In the eulogies, one friend spoke of Tonio’s love of quoting a line of the painter Francis Bacon: “It is all so meaningless we might as well be extraordinary.” Anna Trzebinski wrote in her valedictory,

“Had I known what was to come I would have been able to let you fly. But for selfish reasons I hung onto you out of love. Please forgive me.” Tonio’s son, Stas, put the first torch to the kerosene-soaked pile, which went up like a rocket into the blue sky. “We did it in the spirit of who we are,” said Anna. “There was such integrity.”

The reporters did get some things right. Two former girlfriends stood on a nearby hill waving silk banners. And Natasha Ilium Berg did—despite family denials—fly over the funeral in a small plane, but she flew high. One of her friends told me she had “begged her” not to buzz the site.

I hadn’t been to Kenya in 12 years, and I was shocked by the state of the nation, the hellishness of Nairobi, the explosion of its slums, the streets where I used to stroll in the early morning smelling incense now unwalkable. The city mortuary was built in 1949, in the colonial bungalow style. Nothing has been changed except for the addition of a kiosk selling soft drinks. Even the refrigerators are original, crammed now with bodies. It was designed to hold 145 and today stores between 700 and 800. As I walked in, a stench that I hadn’t encountered since Vietnam hit me, but Dr. Alex Kirasi Olumbe, the chief government pathologist, seemed to be immune to it. Covered bodies lay on tables, swarming with flies. There was no air-conditioning. Dr. Olumbe, who is paid around $3,000 a year, told me he is considering moving to Australia, where he was trained. This is where Tonio’s body, lying on the floor, his shoes stolen, was collected by Aidan Hartley and Martin Dunford, his surfing buddy. The security firm had been instructed to take him to Lee Funeral Services, but it had misunderstood. It was there that he was finally transported, and where Dr. Olumbe performed the postmortem.

I filed in with other supplicants to see Geoffrey Muathe, Nairobi’s police chief. When Muathe, who is an imposing man, suddenly snapped, “Fox!,” I jumped. “It’s Tonio?” he asked. Why else, he assumed, would a journalist from London be in his office? “Love triangle, love triangle,” he continued. “That’s all you people write about. But this is murder.” It had, in fact, been the police who first revealed the story of marital problems between the Trzebinskis. Angry E-mails between Anna and Natasha Blum Berg had been described as “threatening and nasty,” and, according to the police, Anna had finally said that her rival “could have him.” But the police also revealed that they had found Tonio’s SIM card from his mobile phone—the removable memory chip—in the possession of Raphael Nyagah Mutira, a car mechanic who worked barely half a mile from the scene of the shooting.

when you were with Tonio, it was like magic dust was falling all around’ said his friend Julian Ozanne.

Muathe told me to call the following day, when he revealed that the card had been used to make calls immediately after the shooting and again within 24 hours, calls traced back to Mutira and two other men through phone-company records and interrogations. In these conversations, said Muathe, “there was mention of the incidents of the murder.... We are fairly certain that it is them. But I can’t say they’re the only people involved.” In the meantime, the accused, charged with a capital offense and unable under the law to enter a plea, had been sent to the fearsome Kamiti Maximum Security prison while evidence was gathered, on the basis of which the High Court would judge whether to put them on trial. The process takes months. Dr. Olumbe predicted that after their stay in prison they would most likely turn up in his mortuary dead from tuberculosis or AIDS.

It was almost certainly a caijacking. But the early lack of evidence led to wild speculation and conspiracy theories, at which the white community of Kenya has always excelled: Why didn’t they take the money? (Probably because they had less than two minutes after the alarm to avoid meeting armed police head-on on a narrow road.) No one steals Alfas—they can’t sell the parts. It was a contract hit. Tonio was invoked in importing cocaine from Mombasa. A jealous rival for Natasha had lain in wait. (Natasha’s fiance, a former British Army officer named Sebastian Willis-Fleming, had been away in Nigeria for three months on a U.N. peacekeeping mission.) The speculation moved between soap opera and black farce: One woman in Karen actually said to me, “It was her,” referring to Anna Trzebinski. “She’s so clever.” Natasha, who came in for some serious vitriol, went into seclusion. When I left Kenya, several weeks after the murder, she was still being questioned by the police. A friend of Tonio’s described Natasha as beautiful in a kind of “severe Danish way.” A woman friend said, “She was a muse of a kind for Tonio. She is what people call her, ‘the ice maiden,’ but she’s got more character than that. She’s quietly elegant. She has poise, model looks. Reports of her predatory nature are highly exaggerated probably.”

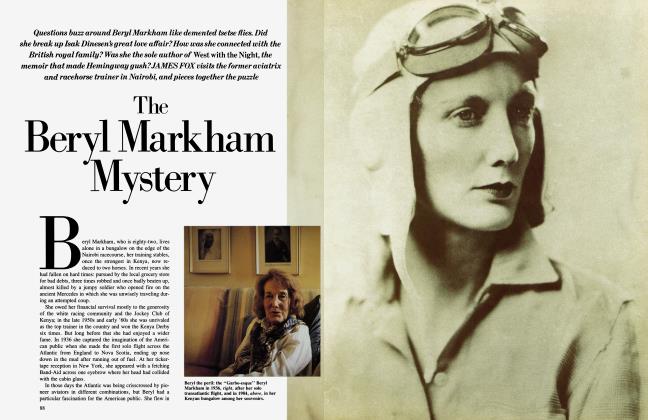

The strangest theory was put forward by Tonio’s mother, Errol Trzebinski, who has written several books, including a biography of the aviatrix Beryl Markham. In The Life and Death of Lord Erroll, which was published in 2000, she claimed that British intelligence killed the earl, who had once been a member of Oswald Mosley’s Fascist Party in England, because he knew too much about secret dealings between the British government and the Germans at the start of World War II. She based this on one document she had obtained, called the Sallyport Papers. The problem was that neither the document nor Errol Trzebinski could produce corroboration or proof for the theory, or even, in her 300 pages, tell what information Erroll had that was so threatening. To most critics, the document was clearly an invention of the Papers’ author, and the book received predictably devastating reviews. Phillip Knightley, distinguished for his unparalleled knowledge of the British intelligence services, concluded, “If Lord Erroll was really killed by any section of British intelligence for the reasons set out in this book, then I will eat this review word by word.”

I gave Errol Trzebinski help on her book, though she kept its premise secret. She felt certain she had information that would rattle the British establishment and possibly bring down the British government. The plot, she still says, had to do with Churchill and the royal family, and she persists in the view that British intelligence is actually after her 60 years later, tapping phones and stealing computers, even burning down her weekend house. (Her husband, Sbish, said the house was burned down because he hadn’t paid the staff.) Errol now provided headlines with an interview in The Daily Telegraph, four weeks after the murder, drawing attention to her book and linking Tonio’s death to the same secret forces. She and I have, as it were, agreed to differ. “I know how it works,” she told me. “I’ve been studying it for five years [and] I’m not giving up on it.” As if to confirm her fears, their other house, at Shanzu, was ransacked in their absence on December 28; their youngest servant was hacked and left for dead. Their daughter, Gabriela, was due there that night, but she had changed her plans. Errol has decided to leave Africa for good. “How much more can one reasonably take of this kind of thuggery?” she wrote me.

Anna Trzebinski picked me up at my hotel in a battered jeep, looking extraordinarily calm for someone who had barely slept since her husband’s death less than three weeks earlier. Her children, Stas and Lana, were digging a mud bath for the family of warthogs that often emerge from the forest that rises up near the house. In this place of grief, I was struck again by the politeness and friendliness of Kenyans; the servants moved about quietly, making a fire, bringing food, asking if I wanted anything. Sitting at the dining table was a large group of silent women stitching ostrich feathers and beads onto pashminas and coats of ostrich leather, the products of Anna Trzebinski’s business, destined for Donna Karan’s company in New York.

“Tonio had two desires,” said a friend, “to go surfing whenever there were waves and to become a successful painter.” The walls are lined with his paintings—frenzied, intense, the paint thickly applied. His catalogues show him attacking his canvases almost physically, bared to the waist. They are clearly derivative of Bacon, Georg Baselitz, de Kooning, the drawings of Giacometti. It’s rare for a painter as young as he was to break new ground, and there was no breakthrough, nor yet any marked originality. But he was a competent painter, well instructed. Alex Corcoran, a director of the Lefevre Gallery in London, gave him his first oneman show in England. “When you take on an artist, you’ve got to try to think what the work will be like in 10 to 15 years,” he said. “I saw something in Tonio. I knew he had the ability to do it. The tragedy is that he was very nearly there.”

Tonio’s parents, Sbish and Errol, had moved to Shanzu, near Mombasa, when Tonio was 10. Sbish worked as an architect, mostly designing hotels for the booming tourism. Tonio grew up a “coastal boy” until he was 13, when he was sent to the grim, third-rate boarding school in England where Sbish had gone before. “It really hurt him,” said Sbish, “and he never forgave me. He hated England.” Tonio took himself out of boarding school at the age of 16 and enrolled in a “crammer” school. From there he proceeded on grants and prizes to the Byam Shaw School of Art, the Chelsea School of Art, and the Slade School of Fine Art.

The epic of Tonio’s flamboyant life began when he returned to Kenya in 1988. He started a relationship with Sally Dudmesh, an English-born beauty, who now lives in Karen, in an old colonial house owned by the Kenyatta family, which was used for Karen Blixen’s house in the film Out of Africa. “He was drop-dead handsome, very possessive, intense, unforgiving, a fiery personality. If I talked to another man he was extremely jealous. He was a free spirit. He didn’t seem to have material needs; he seemed completely uninterested in money,” Dudmesh told me. “When he fell in love with me, he gave everything of himself completely and utterly, and he demanded 100 percent of me. Any man who pays that sort of attention to you becomes an irresistible force.” They lived together on a farm in Ulu on the Mombasa Road, and then in Kilifi, on the coast.

Tonio, she said, was driven by adventure and danger. They went off to India on a motorbike, then to Sumatra. Trapped in a forest by a gang of men with knives, Tonio did a skidding turn and escaped. “It was extraordinary,” she recalled. “His body, as I held it on the bike, was doubled in size, blown up like a puffer fish.” For two years, she said, Tonio begged her to marry him, but she resisted. Finally she agreed. Sally went to London to see her parents and to buy a wedding dress. “He wrote to me every day, up to the New Year.” Then Sally got a call, not from Tonio but from Anna. In Sally’s absence, Anna, who had known Tonio as a child and who three months previously had married her boyfriend of many years, met Tonio again for lunch. “And,” she said, “I literally had to leave halfway through. I went home and I threw up. I thought, I’ve just met the man I want to spend the rest of my life with.”

To celebrate New Year’s, a group of people, including Anna’s family, assembled on Funzi Island. Anna was expecting Tonio, who had gone surfing in Mombasa, but he was not on the last ferry. “I thought, I know he’s coming, and out of the moonlight appeared Tonio. He’d got a guy to paddle him for a couple of hours in a dugout canoe.” Anna’s husband had been bitten by a centipede, and had had to take so much antihistamine that he fell into a deep sleep. “At four A.M.,” Anna said, “Tonio got up in front of the entire congregation and said, ‘I know exactly what this woman needs.’ He took me by the hand, ... took me into the bushes, and made love to me, and then he disappeared in the same dugout at dawn, because he didn’t want to face everybody.” Anna laughed at the memory, and excused her behavior by saying that her parents had forced her into her marriage and it had been a mistake. “I called Tonio’s girlfriend in London,” she said, “because I didn’t feel that what I had done was right.” Anna told Sally that she was with Tonio and that she was getting a divorce.

“I didn’t believe it,” said Sally. “I thought it was a joke, and that he’d come back to me.” In fact, he did go back three times during the next six months, but finally he and Anna were married on a trip to California. “All Sally’s friends thought that was pretty caddish,” said Willy Knocker, an old friend of Tonio’s who is an environmentalist.

The first three years were like a rocket— J. incredible, unbelievable,” said Anna. “I promise you, we’d walk into a room and people would think ... we weren’t anybody, but they must have thought we were like Nicole Kidman and Tom Cruise: Who the hell are those two? Wow, who are they? And the energy between us! There was something that made people think, Jesus Christ, this is unbelievable that this exists.” Their heyday was the early and mid-90s, when the fun squad assembled: Julian Ozanne, Aidan Hartley, and former London Times reporter Sam Kiley, who made up the hard core, were reporting on the conflicts in Somalia, Rwanda, and Sudan and returning to base for R&R, mostly at the Trzebinskis’.

“We just lived this fantastic life,” Anna recalled. “I had some money—not much, but I had a little. Suddenly Tonio could afford the surf trips, and we had a real blast. We were wild with a capital W. Ecstasy had been invented. We also did a lot of coke, and stayed out very late. Julian and Aidan and Sam would fly in from the war zone on weekends, and Friday night we’d meet at the Tamarind in Mombasa and party till five in the morning. They just loved us, because Tonio and I exuded this energy that you can’t believe. And we were just such a beautiful couple, and I loved him so much, and he loved me so much, and I bore him beautiful children. It was a wild, fantastic time, totally sublime, no gray, the highest highs. If we moved in anywhere as a group, there was no space for anybody else.”

“They were the most magical times I’ve spent in my life,” said Julian Ozanne. Lars Korschen, another friend, remembered a dinner at Alan Bobbe’s Bistro in Nairobi where they cleaned out the restaurant’s entire supply of caviar and vodka, with Tonio, as ever, waving off the others’ attempts to pay.

Part of the devastation for Tonio’s closest friends when he died was that they had become dependent on him as their driving force. “You gave me an identity that is impossible to think can exist without your energy, passion, stubborn determination, your irritating sixth, seventh, or eighth sense for land, sea, the earth,” said Julian Ozanne at his funeral. Ozanne told me, “When you were with Tonio, it was like magic dust was falling all around. He made you feel that life was precious and exciting and that with him you had a front-row seat looking onto the greatest show on earth.”

One New Year’s Eve, they went to Lake Paradise on the top of Mount Marsabit. “Francesca and Aidan and Tonio were all there,” said Anna. “Elephant herds were coming to the lake and swimming, and because of the acoustics you could hear every chomp of grass, their tusks hitting together. It was so idyllic, and we all loved each other so much.”

Tonio divided his friends into compartments. For surfing, it was Martin Dunford, the chairman of the Tamarind hotel group, and Bruce Hobson, a prominent gardener. Tonio would travel with them to Mauritius, Reunion, Timor, Hawaii, and Mozambique, on trips that excluded girlfriends and wives. They became “the fun bandits,” “the Mombasa marauders.” “We sucked in all the fun available in any situation,” said Dunford. Nick Rabb added, “Tonio was a huge presence in the ocean. He was a huge presence in life, but get in the ocean and he was the fittest, the youngest, and probably the most active of us all, and the most passionate.” One day Hobson watched across Mombasa Harbor as Tonio rescued a dolphin caught by the tide in shallow water inside the reef. “He put his arm around the dolphin and had his leash tied around it, and he was paddling with one arm against this fierce incoming tide, the other tugging the dolphin, and he tugged it out to sea. It was a wonderful image.”

His Swahili nickname among the fishermen from Malindi to Lamu was Chonjo— roughly “ever ready.” His fishing buddy was Lars Korschen, who owns the Peponi Hotel in Lamu, and the bar there was Tonio’s favorite in Africa. The bartender, Charles, created a drink called the Tonio, which is simply a quadruple vodka-and-tonic in a huge glass. “Tonio was a very competitive guy,” said Nick Rabb. “He wanted to win; he wanted to be the best, get the biggest fish, get the most fish, get the first fish. It was a real driving force in his life, and he used to have sulks.” Bruce Hobson remembered one sulk, on a boat, that lasted a whole day. “He actually read a novel. Which he’d never done before. So we knew he was sulking.”

Tonio predicted to Korschen that he would die before he was 45. “The way he lived his life, it would never have been surprising,” said Korschen. “It’s the real James Dean story. He died wild, fast, and young.” Tonio repeatedly took the risk—unheard of in deep-sea lore—of fishing for the sharpbilled marlin 10 miles off the coast in a rubber boat with a 25-horsepower motor and no radio. Two years ago, more mundanely, when a deranged man held a gun to Tonio’s head for many minutes on the causeway at English Point, in Mombasa, as he was going out to surf, Tonio talked him down.

When the fun squad traveled to London, the razzmatazz was turned up many degrees. I remember wondering whether this was compensating expatriate behavior. The combination of all this loud energy revved up on powder was almost overpowering for one woman who invited Tonio for dinner: “I thought, Just go and have one huge line instead of jumping up every 10 minutes.” Anna herself recalled, “He would be like a Damien Hirst and go into overdrive all the time we were in London. Last time we were there, I was at the end of my tether for three weeks solid. They’d come home at five in the morning. I was in bed by 11. . . . After these guys went on the razzle for three days, they walked in out of their heads at 7:30 in the morning, and I just said, ‘You better stay out of my way. Three days is beyond the limit.’”

Some people were allergic to Tonio’s arrogance and the loud and beautiful people. Francesca Marciano said, “Being Polish, he was haunted, tormented, extreme. He was destined to live in Africa; he couldn’t have lived anywhere else. He could also be impossible—a bully. He lived in a world where he ruled, because he knew the place inside out. Kenya does that to people.”

One man I lunched with in Nairobi said he was playing golf when he was asked if he was going to Tonio’s funeral. “I replied, ‘No, I’m not. I couldn’t stand the guy.’ He was worse than cocky. He enjoyed humiliating people.” He described watching Tonio at the Tamarind hotel in Mombasarun by Tonio’s surfing friend Martin Dunford and designed by Tonio’s father—when Tonio was refused a room because the hotel was full. “He started shouting, ‘I don’t give a fuck whether it’s full. You just throw someone out of their room.’” If that’s the case, I know where it comes from. His father, Sbish, has the same manner. There is justification in the descriptions of him at the Tamarind, where he has credit in return for designing the place, as “the customer from hell” or “the ranting gargoyle.” “I had a lot of enemies,” Sbish told me. “And a lot of people thought I was bloody wonderful.”

There is reason for Sbish’s enduring angst, his temper. His father, a commander in the Polish Navy, and his mother, both from eastern Poland, were split up after the Russian invasion of Poland. Sbish traveled with his mother in cattle wagons to Siberia, where they lived for three years on a collective farm, knowing nothing of his father’s whereabouts. Later, under Russian amnesty, they were released into another nightmare journey, during which his mother worked as a waitress in Tashkent, Uzbekistan. They ended up in Glasgow, Scotland, and were reunited with his father in 1944. Sbish immigrated to Kenya and brought his parents out in 1957. His mother, aged 90, still lives on his compound in Shanzu.

“Tonio was the kindest, most insecure person I’ve ever met in my life, which is where his aggression and arrogance came from,” said Anna Trzebinski. “He couldn’t just walk quietly into a bar and sit down in a corner. The only voice you’d end up hearing in the bar was Tonio’s. I remember looking at him and sometimes thinking, Oh my God, I’ve got to live up to this. If you didn’t know Tonio it was very easy to misunderstand him, find him arrogant, condescending, opinionated, and rude, and sometimes he was. Sometimes I am. Maybe sometimes you are ... Then you’d realize that there was much more to Tonio than that.”

There were tensions in the marriage, a clash of two powerful egos, with Anna relentlessly using social contacts to get Tonio’s work on the map, and Tonio developing a paranoia about being controlled. “He wanted to be a poete maudit,” said Francesca Marciano, “and he ended up in luxurious circumstances. He was a bird who wanted to fly away from it.” According to Anna, “Tonio started going out of control when I had the kids. We went different ways. And because of the children, and him coming home at five A.M., and a lot of wildness going on, I felt pretty lonely. So drugs became an issue in our relationship for a while, and when it became an issue it became secret, and with that came lies.”

The Trzebinskis’ circle agreed that Anna isolated Tonio from any women friends and became possessive and controlling. “She had a consuming jealousy of any other woman being near him, to the point of paranoia,” according to a friend. “Often at dinner with them,” said one woman, “we wouldn’t see them at the end of the evening. They were fighting upstairs.” In 1998, Tonio ran off with Saba Douglas-Hamilton, daughter of Iain Douglas-Hamilton, Kenya’s leading elephant expert. As far as his friends knew, it was the only time he had been unfaithful to his wife. Under family pressure, and for the sake of his children, they broke off the affair, but it was messy. In the summer of 1998, in a ceremony at Montauk, Long Island, near Peter Beard’s house, Tonio and Anna renewed their marriage vows. In Anna’s words, “Oysters, clams, Cristal champagne—he was down on his knees in tears, saying, ‘You’re the most incredible thing in my life, and you and the children are the only important thing until the day I die.’” But, Anna added, she realized a year and a half later that the trust had broken down between them.

Tonio took up with Natasha Ilium Berg some three months before he died. Whether it was a sexual affair or not—and it seems that it wasn’t—hardly mattered. It was a secret friendship and therefore, in Anna’s eyes, a betrayal. It’s clear from her friends that Natasha fell in love with Tonio, and it was serious enough for Tonio to say he needed, if he was to start a relationship, not to see her for a while in order to arrange his life and settle his affairs. Anna had met Natasha several times, and predictably didn’t like her. She had once, she told me, even insulted her to her face.

On September 26, Anna’s lurking instinct about Tonio’s changed behavior came to a head when, exceptionally, she asked a servant to pick up her children from school in the Alfa Romeo that afternoon. “I thought to myself, If I know Tonio, he’s going to hear my car go, and wait 15 minutes; then he is going to leave on his motorbike, and if he does, I’ll know there’s something up.”

When Tonio got on his bike, he unleashed a cataclysmic train of events. He actually went to the local shopping center to buy turpentine. Tonio kept his studio locked at all times; even Anna entered only at his request. Anna called the gardener to get a ladder and climbed 30 feet to his studio window. She said, “I was praying every step along the way that I was wrong. I picked up the telephone and hit the re-dial button, and I get a woman’s voice. I’m praying it’s the mechanic’s wife, and I say, ‘Who is this?’ She’s aggressive. She says, ‘Who am I talking to?’ She has a Danish accent, so I knew it was her. My heart sank. My whole universe collapsed. Then he walked in and was furious. He said, ‘I will not have you intrude like this.’ I said, ‘Tonio, I’ve just spoken to Natasha,’ and his face went white. And the reason I then really lost my cool with him was that he started attacking me: ‘You’re so possessive, you will never let me have a girlfriend.’”

Tonio’s huge studio, the size of a small riding school, still has the marks of the fight that followed—an overturned turpentine bucket by the wall, stains all over the floor. “I said to him, ‘I want you to feel the pain that I’m feeling right now,’” said Anna. “I didn’t recognize the voice that came out of my mouth. I was screaming.” She picked up a Stanley knife and slashed at a painting whose face was to the wall until the blade broke. “He picked up a pair of scissors and said, ‘Why don’t you just hurt me? I was completely somewhere else. Tonio had to whack me one. He slapped me in the face, and that really worked. Actually he gave me a black eye. Then I was quite calm. I said, ‘You’ve got to leave. I’m not going to accept this. I don’t care if you are or aren’t having an affair. You can’t have a secret friendship with another woman. Take your stuff and leave.’ And that’s what happened. That’s the last time I ever saw him.”

Anna sent an angry E-mail to Natasha, saying she was getting divorced and would name her as the cause, “and that I hoped she enjoyed him and fuck off.” She soon regretted this and retracted it, but it was their exchange of E-mails that sent the police down the road of the love triangle.

I went to lunch with Michael CunninghamReid, Anna’s stepfather, in his grand stone house, with its vast trimmed garden, almost a mowed park with stands of trees, on the Ndege Road in Karen. The road that runs alongside the estate was once the landing strip for the biplane of Denys Finch Hatton, Karen Blixen’s lover. Down this road, Cunningham-Reid’s German wife, Dodo, Anna’s mother, a major social figure in Nairobi, was chased twice by car gangs armed with AK-47s in recent months, before she escaped into the estate. Cunningham-Reid has that self-effacing, patrician confidence of some of the old settlers—and the same kind of frank humor and pronouncement bred in the Aberdares which provided White Mischief with its best archaeological findings and many of its best jokes. He and Dodo live six months of the year in Newmarket, England, and the rest in Kenya, much of it spent billfishing on the coast. The large drawing room, with its polished floor, outsize sofas, silver cigarette boxes, and game books, has that unreal English country-house grandeur that seems so odd in Africa, but that in Kenya was still a commonplace 30 years ago. On the mantelpiece is a picture of Broadlands, the house of his uncle, the late Earl Mountbatten.

When I asked how he had gotten on with Tonio, he said, “I adored him—I’m not queer—because he liked me so much. There’s an honest answer.” Tonio, he said, would come to him to pour out his problems about his marriage with Anna. “Tonio was completely egotistical. I frightened him when we were out on the boat, because I can be very nasty. But he had enormous staying power. He would sit on the boat for hours looking for deep blue water, looking for dolphins, seagulls. Tonio was always looking for a piece of bush where no one had been, or always trying to get away from people. But he was an intensely loyal man, sometimes against his better inclinations. With women, it’s give-and-take. You give and she takes. Anyone knows that. Tonio never accepted that, and so he never had any peace.” I asked if he thought their marriage would have survived. “No,” said Michael Cunningham-Reid.

Our lunch of roast chicken and apple pie was served by a tall, beautiful Kikuyu butleress, who spoke perfect English. At one point, however, when it seemed she hadn’t heard some request of his, Cunningham-Reid said, “Amuka,” meaning “wake up.” He went on to say that the staff tended to slack, because he and his wife were away much of the time. The woman didn’t seem to mind; she was clearly quite used to this old-style communication of the English proprietor.

Cunningham-Reid had come out to Kenya in 1948. “My stepfather [Tom Delamere, son of the leader of the Kenya settlers] said, ‘You can scarcely put pen to paper, you’re practically illiterate. No one in the City’s going to take you—you’d better come out to Kenya with me.’” I asked him if he kept in touch with any of the older settlers. “We didn’t really have much to do with them. We were far too grand. We were Delameres, Happy Valley, Lady Idina!” He got on well with Diana Broughton, who married Tom Delamere in 1955—her fourth marriage— thereby turning herself from the scarlet woman of the Erroll scandal into a kind of white royalty. Then he told me something I wish I had known all those years ago, which clinches my conclusion that Diana’s then husband, Jock Delves Broughton, was indeed the murderer. “Diana always used to say to me, ‘If a woman could have given evidence against her husband, he would have hanged.’”

I heard on this trip of Diana’s last, fantastic journey. John Lee, proprietor of the funeral parlor where Tonio was embalmed, told me he drove Diana’s body at two A.M. one night in 1987 to the Delamere ranch for burial. On the way he stopped at the crossroad where Lord Erroll had been shot, put the coffin on the ground, and had, he told me, “a couple of beers in the moonlight. I thought, If the secret is ever going to come out, now will be the time.”

Many whites felt doomed at independence in 1963, but they seem more at physical risk now than they ever were during the Mau Mau Emergency that preceded it, when only a handful of Europeans were killed. The residents of Karen-Langata are now living on a new dangerous frontier. Almost everybody in these leafy suburbs with their high hedges and enormous gardens can tell of some close call with violence, even if they haven’t been directly hit.

They are not imagining the danger. According to Dr. Olumbe’s statistics, over the last two years there has been a 50 percent increase in the proportion of homicides caused by firearms. Of these fatal shootings, the police were responsible for more than half. The Nairobi slums fester with guns, violence, and AIDS, the result of a system which, as Dorian Rocco, an agricultural consultant, told me, “if they’d tried they couldn’t have buggered up worse. No attempt has been made to ease the life of the rural population.” Many have ended up in the Kibera slum of Nairobi, into which arms have poured from neighboring wars. But the chilling statistic for the Karen-Langata residents is that, of the deaths by shooting in that period, 35 percent were in the slums, and 37 percent in the upper-middle-class suburbs. Fourteen percent of the victims were shot in cars.

“Europeans are more subjected to armed robberies, whereas Indians get burgled,” Ishan Kapila, a prominent Asian lawyer, told me. “It’s where you live. These guys are crazy, living out in Karen, holding on. They don’t take security measures; they live there because it’s beautiful. Perhaps it’s childish hedonism that we live in Kenya with six maids because we’re all at the top of the tree. Is it worth it? The economy is in dire straits, and we don’t have a police force.”

Many of Tonio’s friends have “gone to the hills,” as one of them put it; Aidan Hartley to Laikipia, for example, to get away from, as he wrote, “Nairobbery.” Surprisingly, Tonio’s journalist friends complained loudly and stridently about this state of affairs, after his death, even though they had covered Africa for many years and knew the ropes. I was told solemnly by Julian Ozanne, “The state has failed to guarantee life, liberty, and property.” “Is this the price of freedom,” Hartley wrote on the subject of his friends dying violently, “or is this the cost of living in a Third World country?” Hartley, the former Reuters correspondent, wildly exaggerated the crime statistics in Nairobi, claiming a “staggering” 3,640 gunshot deaths a year, 70 a week, and demanded more arrests by the corrupt and underpaid police force. What Dr. Olumbe, our mutual and only reliable source, said was that 70 percent of his admissions at a peak last year had died from shooting. His figure for Nairobi gunshot deaths in 1998 and 1999 was 296.

Happy Valley

A part of the romance of the life here was being on the edge, taking the risk, weighing the dangers against the freedom of the playground. Francesca Marciano said, “Many white people who live in Kenya acquire a kind of arrogance that’s impossible to lose. It’s almost too easy, people working for you, always someone carrying your things. After a while you slip into a smugness that your life is better than others’. And it is. You stop agonizing, and everything is allowed. And then the violence. Your friends die, the amount of pain is excruciating: little planes crash, accidents on Mombasa Road, mauled by lion, gored by buffalo, shootings. I went to so many funerals last year. But the balance is even.” Suddenly, to Tonio’s friends, the balance seemed unfairly tilted, unacceptable. The journalist Cyril Connolly wrote, as a coda to the Erroll scandal, “Perhaps Africa was to blame. It insinuates violence, liberates unacted desires.” And now Africa was to blame again, in the eyes of these white Africanists, in the different form of an incipiently failed state, its violent shantytowns bursting with the rural unemployed who come to the upper-middle-class suburbs armed with Russian handguns from Somalia.

Certainly the younger group I met are bound together by a sense of danger, of the intensity of living on the edge. In some ways the figures presented by Tonio Trzebinski and Giles Thornton, who both died young and tragically, are not so unlike the Denys Finch Hatton prototype. The similarity between these white generations is the romantic, possessive view of East Africa. The other former colonies—Nigeria, Ghana—don’t have the romantic Scottish landscapes, the grandeur that still attracts the sons of English families who can’t bear the idea of the city. Karen Blixen was thinking of Finch Hatton when she wrote in a letter in 1917, “Even apart from the natives, one does meet herein the midst of the fearful living death of the English middle class mediocrity—some people who in a completely simple and straightforward way are looking for the primordial values of life. Such for example [is] Lord Delamere.” Karen Blixen didn’t mind if these romantics indulged in aristocratic exhibitionism as long as they were grand enough.

To any black Kenyan reader, the image projected of his country in the British newspaper reports of Trzebinski’s murder must have been unrecognizable. And certainly the passions that Tonio pursued—bush safaris, surfing, deep-sea fishing, impala barbecues miles from nowhere with Dom Perignon on ice—never had much claim on the attention of black Kenyans. The young whites have now become an underclass. The real elite are the rich Kikuyus with their Armani suits and jets, who go home to the country for weekends. Many are the beneficiaries of a kleptocracy that is ruining their country, and they welcome the white businessmen who help maintain Nairobi as the financial and business capital of East and Central Africa. The rest of the whites now struggle, some successfully with farms, others in the tourist trade, others in cottage industries in the suburbs. And life is now expensive. Below them are young white Kenyans, badly educated, who have lost all contact with Europe, who live illegally. There is no integration between these communities. None of these white tribes play any part in politics. Few can face returning to England. Complaints are all they can voice as subSaharan Africa slides toward catastrophe.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now