Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowEDITOR'S LETTER

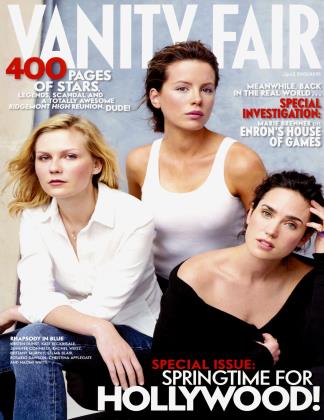

Dream Merchants

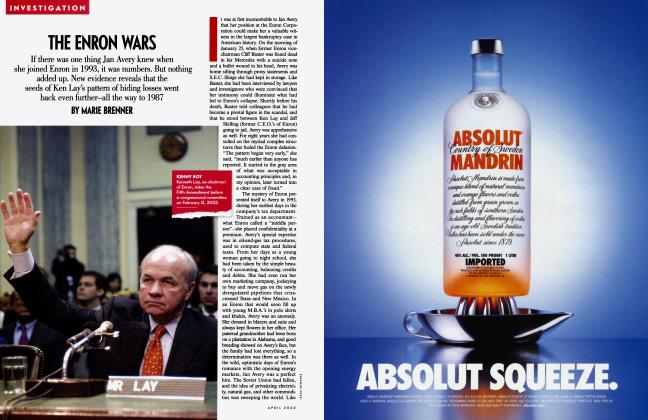

Even those of us who don’t throw around terms like “P-E ratio,” “EBITDA,” or “Aspen condo” have come to the conclusion that Kenneth Lay and his associates at Enron may now be the most hated men in America (if you don’t count Osama bin Laden and his associates). Lay’s actions have not only wiped out the portfolios of shareholders and Enron employees but also changed the way big-league accounting will be done in the future, and may at some point damage the reputations— if not the careers—of senior members of the Bush administration.

When the story broke (I confess I had little more than a passing knowledge of Enron until last fall), I turned to Marie Brenner for a narrative that would go beyond the nuts and bolts of energy trading and shady bookkeeping. And, as expected, Brenner—whose story on the tobacco-industry whistle-blower Jeffrey Wigand became the basis for Michael Mann’s film The Insider— has delivered. In “The Enron Wars,” beginning on page 180, she reveals that Enron’s questionable dealings date as far back as 1987. She also provides a gripping account of the war between the sexes that was being waged at Enron. You probably won’t be surprised to learn that women wore the white hats in this conflict.

A major opponent of Enron’s shell game, Jan Avery, a crack tax accountant with a young daughter, worked at the company for eight years and spent a lot of that time telling executives that their math made no sense. Enron being Enron, her complaints had no discernible impact on the way it did business. Lay, the company’s first chairman and C.E.O., Andrew Fastow, the chief financial officer, and Jeffrey Skilling, who also served as C.E.O., were operating in the topsy-turvy economy that had allowed dot-coms and other “new economy” companies to be valued at astronomically irrational prices. (Last year Enron still ranked seventh on the Fortune 500.) Riding that boom, Enron bought into all the other lunatic elements of the dot-com bubble: namely, that success wasn’t about tangibles (indeed, Skilling seemed to regard assets as liabilities) but about illusions and expectations.

Which in some ways is an apt description of the movie business. Hollywood is notorious for enticing outsiders—and liberating them from their fortunes—with dreams of glamour, power, and introductions to starlets. Joseph P. Kennedy, father of John F. Kennedy, turned that tradition on its head. His four-year foray into Hollywood in the 20s left him millions of dollars richer and a lot of movie-business insiders licking their wounded checkbooks. One of his victims was also his mistress, silent-film goddess Gloria Swanson.

When Kennedy abruptly left both Swanson and Hollywood, as Cari Beauchamp reports, the actress found that the bungalow Kennedy built for her, the mink coat he “gave” her, and the expenses of Queen Kelly, the very costly movie they made together, had been billed to her personal company, Gloria Productions, leaving her with a $1 million debt from which she never fully recovered. Drawing on newly available Kennedy archives, Beauchamp’s article, on page 394, reveals how cannily the 37-year-old Boston financier anticipated the future of the movie explosion, pioneering the consolidation and vertical integration that would become standard for the industry. But, as a 1937 magazine article noted, he left behind him “the ruins of vanished corporations ... from which there arise whiffs of an atmosphere distinctly gamey.” They are words that could easily apply to Enron today. —GRAYDON CARTER

GRAYDON CARTER

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now