Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

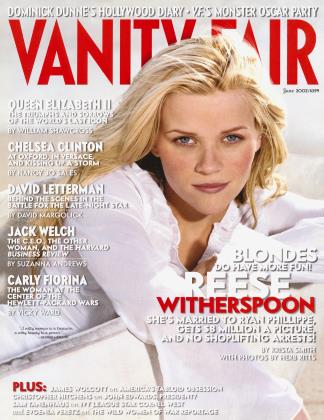

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowHard on the dizzying whirl of parties during Hollywood's Oscar week, the author joined the circus at the Skakel trial. Here's what he learned about the Kirk Kerkorian paternity suit, the delayed arrest of Robert Blake for murder, the Safra case, and the Kennedy offensive

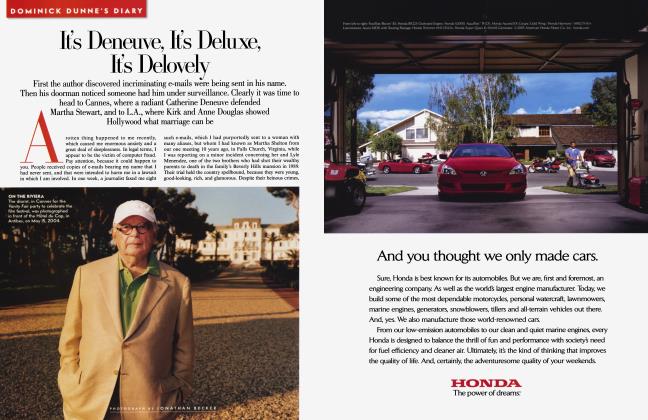

June 2002 Dominick Dunne Patrick McmullanHard on the dizzying whirl of parties during Hollywood's Oscar week, the author joined the circus at the Skakel trial. Here's what he learned about the Kirk Kerkorian paternity suit, the delayed arrest of Robert Blake for murder, the Safra case, and the Kennedy offensive

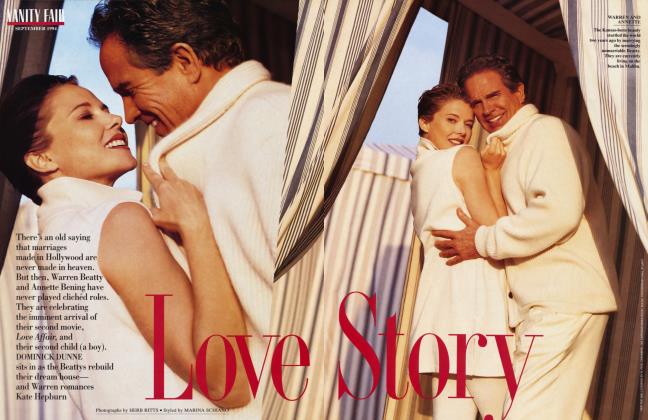

June 2002 Dominick Dunne Patrick McmullanI left Los Angeles and moved back to New York 22 years ago, when my movie career ended and my writing career began, but I always love returning to L.A., whether it's to cover a trial or just to visit the friends I made during the quarter-century I lived in Beverly Hills. For me, Oscar week is the best time of the year to be in Hollywood. It's festive the way Mardi Gras is in New Orleans. The movie community, which is the one I hang out with, talks of nothing else. In conversation, they all use just first names—Russell, Denzel, Nicole, Halle. There are nonstop parties, and many of them are quite dazzling, especially our Vanity Fair party, which ends the festivities and is the one to be seen at on Oscar night. On the preceding nights this year, I went to a number of other affairs, including the Miramax party hosted by Harvey Weinstein at the Mondrian Hotel. Miramax had a passel of Oscar nominations this year for In the Bedroom, Amélie, and Iris, so people swarmed around Judi Dench and Sissy Spacek to wish them luck. I also went to the New Line party, hosted by co-C.E.O. Robert Shaye at his spectacular hilltop house. New Line had a total of 14 nominations, for Lord of the Rings: Fellowship of the Ring and I Am Sam, and Ian McKellen, between dances, was being wished good luck on all sides. At the glamorous outdoor lunch party hosted by media mogul Barry Diller and his wife, Diane Von Furstenberg, some of the prettiest people I ever saw were strolling over the manicured lawns. I went to the party given annually by ICM superagent Ed Limato, who represents such high-voltage stars as Denzel Washington and who lives in a beautiful house with Hollywood history: Dick Powell lived there during his marriage to Joan Blondell, and George Raft lived there during his affair with Betty Grable. The lobby of the Beverly Hills Hotel, where all of us from Vanity Fair were staying, was a scene of continual excitement with all the new arrivals and greetings, and the hotel pool was the hot spot for lunch. One day, I had lunch at the Hotel Bel-Air with my old friends Nancy Reagan and Betsy Bloomingdale. Although the subject didn't come up, for obvious reasons, I later discovered that they had dined the night before at a party given by Mrs. Edmond Safra at L'Orangerie on La Cienega Boulevard. In town to attend the Academy Awards, Lily Safra was staying on the top floor of the Regent Beverly Wilshire, with guards around the clock.

Wendy Stark, a contributing editor of this magazine, and I stopped briefly at one lunch party that looked like a scene from The Great Gatsby. You drove through gates and up a hill to a courtyard in front of an enormous mansion in the Spanish style. I realized immediately that I had been there before—in the late 50s, it must have been—when Marion Davies, the movie-star mistress of William Randolph Hearst, lived there. The current owner, Leonard Ross, a Los Angeles business tycoon, has restored the house to look exactly as it did in Hearst's time. In the library is a full-length portrait of Davies, dressed all in pink, which was used in one of her movies. The pool at the far end of the garden is as magnificent as the pool at Hearst's famous castle, San Simeon, where the popular and witty Marion Davies ruled as chatelaine. She was a far more talented actress and comedienne than Orson Welles portrayed her as being in his masterpiece, Citizen Kane, in which he changed her to a failed opera singer.

I was always fascinated by Marion Davies. Back in the 30s, her sister Rose had been the mistress of my wife's grandfather. He died during an amorous encounter with Rose on his yacht off Miami, and she had to be spirited away so that there would be no scandal. His widow, my wife's grandmother, married again the next day and traveled from California to Chicago with her new husband to attend her late husband's funeral. It was a front-page story in its day. During my years in Hollywood, I became friends with the late Charles Lederer, a screenwriter from the 30s to the 60s, who was the nephew of Marion Davies. Charlie Lederer kept scrapbooks of party pictures taken at San Simeon and at the enormous beach house Hearst built for Davies in Santa Monica. Knowing of my remote connection, Charlie got me invited to a party at Davies's house. Hearst was dead by then, and the Hearst sons had frozen Davies out. On the day Hearst had died, the company stopped delivering the first edition of its afternoon paper, The Herald Examiner, to her front door, something it had done all through the years of their long romance. Davies later married someone else. She was old, a bit blowsy, and a little drunk the day I went there, but you could still see that she had been a beauty. She was sitting on a sofa holding a glass of champagne, and two of her great friends, Mary Pickford, the silent-film star, and Hedda Hopper, the Hollywood gossip columnist, were propping her up, taking care of her. It was like a scene from Sunset Boulevard.

I wrote to Cardinal Law saying I thought he should resign.

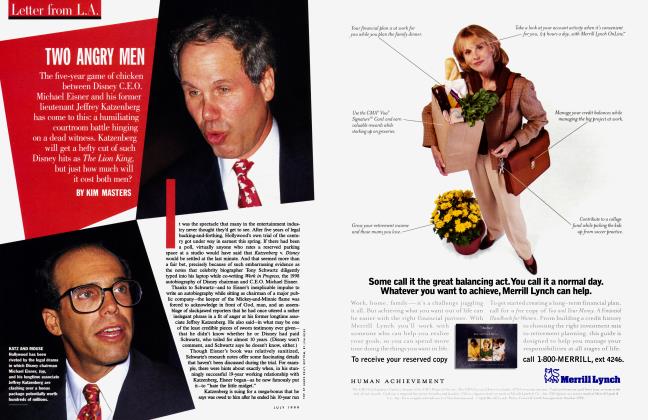

It was the big-money crowd, as opposed to the movie crowd, who were at the party on Ross's terrace, having drinks before lunch, and the most frequent topic of conversation was Hollywood financier Kirk Kerkorian, the 84-year-old multibillionaire who had become involved in a paternity suit of epic proportions with a 37-year-old former tennis pro named Lisa Bonder, which was being covered in vivid detail by Ann O'Neill in the Los Angeles Times. Kerkorian and Bonder had had a five-year affair and she had become pregnant. Kerkorian, whom I know, scrupulously avoids publicity, and, though he was married twice, has never really been the marrying kind. He never had any intention of marrying the tennis pro, who gave birth to a daughter named Kira.

According to Ann O'Neill, Kerkorian was extremely generous to Bonder, giving her an $8 million house, $3 million for renovations, and an allowance of $50,000 a month for the child. Kira's first-birthday party at the Hotel Bel-Air cost $70,000. She had three nannies. Bonder, however, wanted her daughter to have the Kerkorian name, so the parents worked out a deal whereby they would marry for a month, which they did a year and a half after the birth of the baby. Then, as agreed upon in advance, they divorced, but now little Kira was Kira Kerkorian and Lisa Bonder was Lisa Bonder Kerkorian. But Lisa wanted more. She took Kerkorian to court to raise the child's support to $320,000 a month, or less only if she could have the use of Kerkorian's private jet. Kerkorian said in court papers that she had engaged in a six-year campaign to part him from his money. He referred to Kira as the "defendant's daughter," not as his own, for he had reason to believe that the child was not in fact his. Bonder's onetime close friend Darrien Iacocca, the ex-wife of Lee Iacocca, former head of both the Ford and Chrysler motor companies, testified that Lisa had told her she was having an affair with a writer-producer at the same time she was having the affair with Kerkorian. Iacocca said Bonder had told her that blood tests proved Kerkorian was the father, but it later developed that Bonder had faked the tests by collecting a swab of saliva from Kerkorian's adult daughter, telling her that it was for her teenage son's science project, and then submitting it, together with a sample of Kerkorian's DNA, to a lab in Seattle. Bonder responded to her old friend Darrien by calling her "an opportunistic social climber" who "would do anything to ingratiate herself to Kirk." Kirk Kerkorian, meanwhile, had submitted strands of his and Kira's hair for DNA testing, which proved conclusively that he was not the child's father.

The sympathy of the crowd on Marion Davies's old terrace was completely on the side of Kirk Kerkorian. As I was leaving L.A. a few days later, I learned that the judge had ruled that Kerkorian had to pay nearly half of Bonder's $500,000 legal fees. This story is still in the works.

I'm the kind of Catholic best described as lapsed, which means I'm not a regular at Sunday Mass, but, at the core of me, I'm very much a Catholic, brought up in the kind of family that had priests, and occasionally a bishop or an archbishop, to dinner. In fact, my brother the writer John Gregory Dunne was named after Archbishop John Gregory Murray, who had married my parents. When my time of departure from this life comes, I'll most certainly telephone St. Patrick's Cathedral, which is close to where I live in New York, and ask for a priest to come over quick and administer the last rites.

But what about this church pedophilia scandal? I'm horrified, embarrassed, and ashamed every time I hear of the latest episode of the rampant sexual molestation of children by Catholic clergy that has been front-page news for weeks now, shockingly dramatized recently by the suicide of a priest against whom charges were about to be made public. I watched a kindly-looking priest on television being taken off in handcuffs from the courtroom to jail. He'd been accused of molesting as many as 130 young boys. What is worse for me, though, is the fact that certain cardinals, particularly Cardinal Law of Boston and Cardinal Egan of New York, have participated in cover-ups of known molesters by having them transferred to other parishes or sent for brief stays in psychiatric institutes, and in payoffs amounting to millions of dollars in order to buy the silence of the families of the molested. Is that where the money hardworking people drop in the collection basket each Sunday has gone? No wonder so many parochial schools are falling apart for lack of repairs, or closing down altogether. I wrote a letter to Cardinal Law saying I thought he should resign, a week before Newsweek put him on its March 4 cover as an emblematic figure in the scandal. I have long been critical of Pope John Paul II for his backward stands on such crucial issues as celibacy of the clergy, women in the priesthood, gay rights, and birth control. Even today, Irish Catholic gays are not allowed to march as a group in the New York St. Patrick's Day parade, which goes past St. Patrick's Cathedral on Fifth Avenue. This seems to me the height of hypocrisy, especially after I heard a priest on Meet the Press, in a full hour Tim Russert devoted to the subject of the current troubles, say that between 30 and 50 percent of priests are gay—a statement another priest on the show promptly challenged. I hear that many priests have stopped wearing their Roman collars in public, in order to avoid rude remarks and hostile looks. The Pope, these days, looks noticeably weaker each time he is photographed, and he was not able to perform some of his usual functions over the Easter season in Rome. My fervent hope is that the College of Cardinals has enough forward-thinking members to find the right man to succeed him.

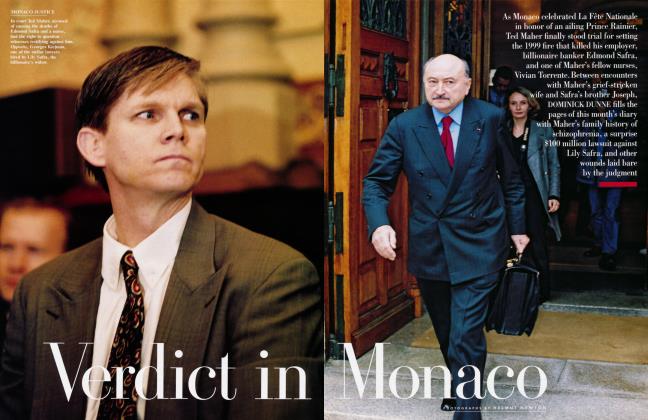

The news from Monaco is not good for Ted Maher, the American male nurse who is in prison in connection with the death by asphyxiation of Edmond Safra, the billionaire banker who mysteriously perished in his Monte Carlo penthouse more than two years ago, along with a nurse named Vivian Torrente, who supposedly had unexplained marks on the back of her neck when their bodies were found in the specially constructed bathroom bunker, which proved to be an inadequate "panic room." A new development on Vivian Torrente's death has recently come to the fore in, of all places, the Bergen Record in New Jersey. Mrs. Torrente was a resident of Bergenfield, New Jersey. What has hitherto never been reported is that her widower husband, Irineo Torrente, allegedly received a $2 million out-of-court settlement from the Safra estate. Irineo Torrente had hired the Fort Lee, New Jersey, law firm of Maggiano, DiGirolamo, and Lizzi to represent him in negotiating with the Safra lawyers. The firm initially demanded $10 million from the estate, but in November 2000, Torrente fired the law firm and began negotiating directly with the estate, which ultimately paid him the $2 million. Now Michael Maggiano has filed suit against Torrente for his share. The suit asks for $540,969, or 27 percent of the settlement, for the months he negotiated with Safra's lawyers. Prior to the law firm's part in the negotiation, Maggiano claims, the Safra estate had offered Torrente a "negligible sum" to reimburse him for the cost of recovering his wife's body and attending the criminal trial of Ted Maher.

Torrente allegedly received $2 million from the Safra estate.

Monaco has finally closed the investigation of the case. Maher's lawyers were notified on March 29 that the prosecutor is going for the top charge against Maher, voluntary arson causing the death of two persons, when the case goes to trial. The crime carries a sentence of 20 years to life. "I am neither an arsonist nor a murderer—God is my witness," Maher wrote to Monaco's Prince Rainier, in a plea to have the case dismissed. Maher's family is convinced that Monaco is using Ted to preserve its image as a safe haven for the rich. They informed me that results of DNA taken from Vivian Torrente's neck and from skin under Safra's fingernails—which was not Maher's skin—will not be introduced at the trial. Neither will the fire report that described a flare-up of flames an hour after Ted Maher was taken into surgery. "Pretty much the only evidence approved by the courts is Ted's forced confession," Heidi Maher, Ted's wife, wrote to me recently.

The Safra case seems to have become a part of my life, to the point where I sometimes feel as if I am a magnet for it. A few weeks ago yet another New York butler who had once worked for Edmond Safra opened the door to admit me to a New York party, recognized me, and immediately began to whisper things in my ear. It even happened to me at the Vanity Fair Academy Awards party. I was seated between the glamorous Lynn Wyatt of Houston and the South of France, who is a great personal friend of the royal family of Monaco, and my old friend Liz Smith, the gossip columnist. Also at our table were the newlyweds Joan Collins and Percy Gibson, as well as Barry Humphries, better known as Dame Edna, and his beautiful wife, Lizzie, who is the daughter of the late British poet Stephen Spender. Completing the table was Nicky Haslam, the English writer, social observer, decorator, man-about-town, and friend of the famous and royal, who had written critically about Joan and Percy's London wedding, and had now been placed next to Joan, which necessitated last-minute seating adjustments. I was in my place at the beginning of the show, writing in my green leather notebook how scruffy, unshaven, and badly dressed Tom Cruise looked opening the show on Hollywood's most glamorous night of the year, when a jet-set society figure with a title put her lovely hand on my shoulder and said in my ear in a very serious voice, "Dominick, I have to talk to you." I've had enough such experiences since Safra's death to realize immediately what she wanted to talk about. I said, very politely, "Not now—I want to watch the Academy Awards." Whoopi Goldberg was just making her hilarious entrance on a swing, a la Nicole Kidman in Moulin Rouge. As an Academy voter, I didn't want to miss a minute of the ceremony. Exactly four hours and 34 minutes later, however, as Whoopi was saying good night, the jet-set figure was at my side again, a woman with a mission. She didn't waste a minute on Denzel Washington and Halle Berry, who had moments before participated in a historic American moment, but got right to the point. She said that I had to stop writing about the Safra case, that it was unkind to write disrespectfully about a grieving widow. I reminded her that the grieving widow about whom she spoke was at that very moment leaving the new Kodak Theater in downtown Hollywood, where the Academy Awards were being held for the first time, and heading off to Elton John's Oscar party. "Don't shoot the messenger," she snapped, and then repeated the line, adding, "She has nothing to do with the Russian Mafia." I told her, "I never said she did." And I hadn't. The chilly conversation ended there, for movie stars were beginning to arrive at the party. In an earlier diary, I wrote that someone in New York had warned me not to write about the Russian Mafia. Why does this keep coming up? It's a fact that Edmond Safra had collaborated with the F.B.I. in exposing Russian money-laundering.

Billy Wilder, 95, a specialist in bitter comedy and drama, and the director of such film classics as Double Indemnity, Sunset Boulevard, and Some Like It Hot, among about 30 others, died on March 27 at his home in Beverly Hills, with his glamorous wife of 53 years, Audrey, a onetime big-band singer, at his side. For decades the Wilders were the Hollywood couple everyone wanted to know. Billy had the unfailing ability to make the perfect comment, always hilarious, for every occasion. Once, back in the early 60s, at a fancy party in the upstairs room of the old Bistro restaurant, Audrey, in black sequins and white fox, was singing with the band, and she had the whole room charged and yelling for more. I was at Billy's table, and he said, "Now I know what Sid Luft feels like." Luft was at that time married to Judy Garland, who also sang at parties. To have dinner with the Wilders, whether at their apartment on Wilshire Boulevard or at their beach house in Malibu, was invariably a sublime experience, with Audrey cooking, and Billy talking, and people such as Frank Sinatra and Marlene Dietrich listening to his brilliant wit. He had a reputation for being a curmudgeon, but he would take my kids for walks on the beach when they were little, and they loved him. I sat in the box with the Wilders at Christie's when Billy auctioned off his extraordinary art collection, which was an exhilarating and sad experience for them. Billy, however, never could stop buying art, and he soon began collecting again. I talked to Audrey the day after he died. "He looked so peaceful, and then he stopped breathing," she said. No one will ever forget Billy. His movies will be playing forever.

The defense strategy to clear Skakel is beginning to emerge.

For an actor on the skids, Robert Blake got the superstar treatment during his arrest on April 18 for the murder of his wife, Bonny Lee Bakley, nearly a year earlier. He simply took over the news that night and the next morning, and his name was on every television commentator's tongue. There were helicopters overhead as a dozen cops walked up the paved driveway of his sister's house, where he had been living, to take him into custody, handcuff him behind his back, and drive him in an unmarked police car down the freeway to Parker Center, with every second captured on videotape, all eerily reminiscent of the O. J. Simpson arrest eight years ago. For months, people had been saying that the trail on the case had gone cold, but the L.A.P.D. was playing it cool this time, not wanting to repeat the debacle it had made of the Simpson case. Since practically the day after the murder, Blake's attorney, Harland Braun, has protected his client by damning the victim as a lowlife. True, she was a petty grifter and a troublemaker who chiseled a lot of guys out of relatively small amounts of money, and who got Blake to marry her after giving birth to a daughter, Rosie, now three, by proving through DNA testing that he was the father. The world was not a sadder place for Bonny's loss, but Blake's explanation at the time of the murder—that he had dined with his wife, walked her to the car, remembered that he had left his gun in the restaurant and gone back for it, and then found her shot to death when he returned—got laughs on the late-night shows. Nevertheless, he stuck to his story. At the L.A.P.D. press conference after his arrest, Captain Jim Tatreau of the robbery-homicide division said that Blake had killed his wife after twice trying to hire someone to do it. "He had a contempt for Bonny Bakley. He felt trapped in a marriage he wanted no part of," Tatreau said. Blake's bodyguard, Earle Caldwell, who was arrested at the same time in a different part of the city, is being charged with conspiracy to commit murder. Poor little Rosie.

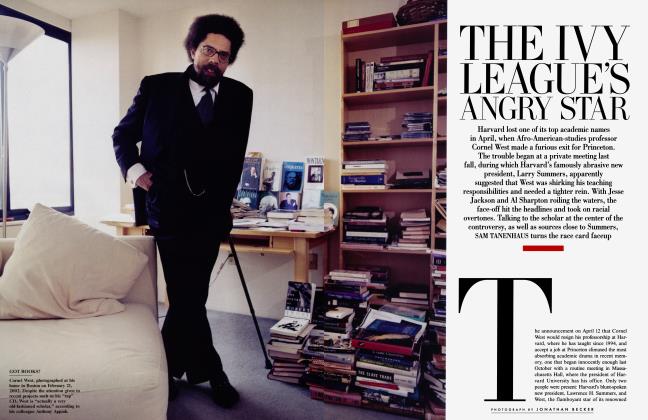

They said it would never happen, but it has. The 27-year-old murder of Martha Moxley in Greenwich, Connecticut, in 1975, has finally come to trial in Norwalk, Connecticut, and the defendant is Michael Skakel, Ethel Kennedy's nephew, whose brother, Tommy Skakel, was the prime suspect for years, until Michael changed his story about his whereabouts on the night of the crime. Michael and Martha were both 15 years old at the time of the murder. One of the things I have noticed over the years in writing about the rich and famous in criminal situations is the reluctance of people with valuable information to come forward even though they are most eager to have the crime solved. They don't want to go to the police for fear of being called as witnesses at the trial, so they contact someone like me instead. "You cannot use my name," they always say. I have had two such people approach me in the last week. With the trial under way, I can't write what they told me, and certainly can't understand why they waited so long to speak out.

It's an odd feeling to unexpectedly hear your name on television. On April 1, the day before jury selection started on the Skakel-Moxley murder trial, I was watching the Today show at my house in Connecticut when Matt Lauer asked Mickey Sherman, Michael Skakel's high-profile lawyer, what sorts of questions he was going to ask prospective jurors. Mickey said he was going to ask them if they had read Dominick Dunne on the case. It gave me a bit of a jolt. The last time I had seen Mickey was at Liza Minnelli's wedding, when he was dancing by Michael Jackson's table with a beautiful girl in a red evening gown.

The next day I attended the first session of the jury selection, and for a moment I thought I was back at Camp O.J., the media city across from the Los Angeles Courthouse, during the O. J. Simpson criminal trial—that's how many reporters and cameramen were there. It will be an even bigger circus when Ethel Kennedy arrives at the courthouse in support of her nephew, and when Paul Hill, the suspected I.R.A. member imprisoned in England as a terrorist in 1975, takes the stand as a witness for the defense. Hill, who served 15 years for two pub bombings, which killed seven people, was declared not guilty in 1989 and released. The film In the Name of the Father, starring Daniel Day-Lewis, was based on him. Hill married Courtney Kennedy, one of Ethel Kennedy's daughters, during the time Ethel's sister-in-law Jean Kennedy Smith was the U.S. ambassador to Ireland. His name was on Mickey Sherman's witness list.

The defense strategy to clear Michael Skakel is beginning to emerge. The plan seems to be to create a reasonable doubt that he committed the murder by pointing a finger at Kenneth Littleton, the live-in tutor who had just been hired by Rushton Skakel, Michael's father. Mickey Sherman has requested any existing forensic tests or examinations of Littleton's blood, hair, saliva, semen, and fingerprints, as well as any psychological interviews, that might implicate him. Littleton has had a checkered life since the murder, but the private-detective firm known as the Sutton Associates, hired in 1991 by Rushton Skakel to remove the cloud of suspicion from his family, worked for nearly three years on the case, ran up a bill of $750,000, and was never able to implicate him. In fact, it was in interviews with the Sutton detectives that Michael Skakel changed his original story about his whereabouts on the night of the murder, thereby placing himself at the scene of the crime.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now