Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowEDITOR'S LETTER

The War at Home

Forget the obfuscations and the deceits that took this country into Iraq. Forget the aftermath: a I war seemingly without end, one that is costing the country a billion dollars and the lives of three American soldiers every week. There is another war, the war at home. This is a quiet, covert, and in many ways more lasting and damaging war. In almost every aspect of American life, the White House over the past two years has chipped away at decades' worth of advances in personal rights, women's rights, the economy, and the environment. It is difficult to point to a single element of American society that comes under federal jurisdiction that is not worse off than it was an administration ago. For starters, how about our finances and our environment?

Has George W. Bush handled our money well? Easy question. The answer is no. Bill Clinton, hardly a wizard with a calculator, nevertheless managed four surplus years during his eight years in the White House. (The highest such surplus: $236 billion in 2000.) Then this happened:

• In 2001, the Bush administration bullishly forecast a surplus of $334 billion for 2003.

• Six months ago that figure was revised to show a deficit of $304 billion.

• And now the administration is projecting that number will be 50 percent higher still, coming in at an astounding $455 billion. It will, in fact, be the biggest deficit in U.S. history, in dollar terms, besting the previous record of $290 billion. That was in 1992, when Bush senior had the job. Never let it be said that the son hasn't lived up to the accomplishments of the father.

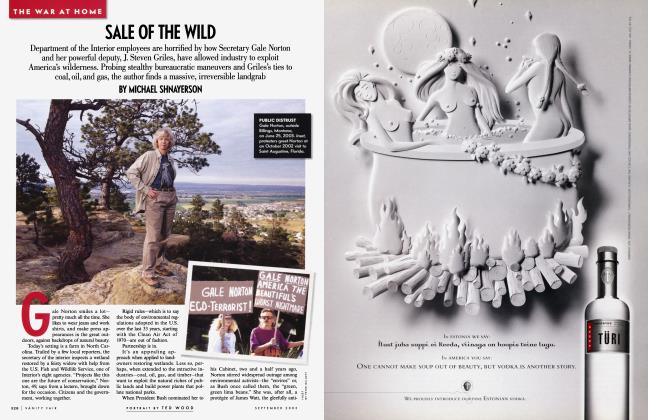

George W. Bush clearly loves his country. But how does he feel about the country—you know, mountains, lakes, forests, and so forth? The thing about the environment is that once you've made a mistake it's difficult to turn back. In "Sale of the Wild," on page 328, Michael Shnayerson has produced a superb investigation of the Department of the Interior under Gale Norton and her deputy, Steven Griles. Shnayerson draws a picture of a government body that is basically dismantling its domain before our very eyes. Or, rather, behind our backs. A few highlights from Shnayerson's report:

• Since George W. Bush came into office, the White House has allowed big timber companies to go into wilderness areas and clear undergrowth that could potentially serve as kindling for forest fires. That part is good. In return, however, lumber interests, critics argue, get to clear those same wilderness areas of irreplaceable oldgrowth trees. This part is bad.

• In the 1990s, a new way of extracting coal-bed methane, which is used in the production of natural gas, was developed. Before companies could drill for it in huge reserves in Wyoming and Montana, environmental-impact studies were conducted. The Wyoming study, which suggested that the drilling be permitted, was given the worst possible rating by an E.P.A official. Despite this negative assessment, roughly 39,000 methane wells were approved in Wyoming by the Bureau of Land Management this spring.

• In 2001, Peabody Energy, the world's largest coal company, proposed construction of the biggest coal-fired power plant in America in decades. But Peabody wanted to situate the plant just 50 miles from Kentucky's Mammoth Cave National Park, which already has the worst air of any national park in the land. After the Fish and Wildlife Service questioned the plan, Peabody met with Fran Mainella, director of the National Park Service. Around the same time, Peabody and one of its subsidiaries forwarded $300,000 in soft money to the Republican Party, and, lo and behold, the process to approve the state permit was put into high gear. Peabody then made a $50,000 donation. Two weeks after the permit was granted, Peabody gave an additional $100,000. So the Republican Party got $450,000 and Peabody got its plant. This chain of events, from the meeting with Mainella to the approval of the plant, took less than three months, though Peabody claims the money was pledged earlier and was not related to the plant. And you think the wheels of government move slowly.

One of Mainella's bosses, Steven Griles, is the quintessential Bush appointee. The second-most-powerful person at the Department of the Interior was not an environmentalist in his past life, but rather a powerful lobbyist for oil, gas, and coal concerns. Now, this really is like letting the fox mind the chicken coop. After his appointment, he sold his interests in his firm for a little over a million dollars, to be paid out in equal annual installments through 2004. Despite claiming that he would recuse himself from matters involving the clients he used to represent, he has continued to meet with those ex-clients.

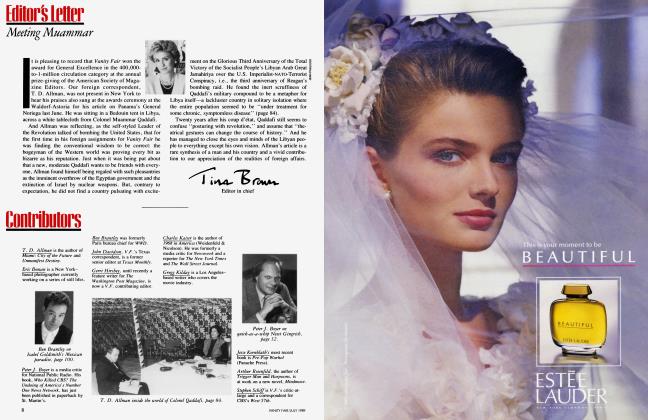

Griles and Gale Norton aren't stupid. When we asked them to pose for pictures to accompany the article, they both said yes; what's more, their representative wanted them to be photographed in outdoor, natural settings. They both look like Sierra Club veterans: Norton in trekking gear and a Patagonia-cum-Smokey the Bear outfit, and Griles on horseback, resembling some latter-day Theodore Roosevelt.

My feeling is this: deceit or untrustworthiness on the part of lawmakers has a tendency to catch up with them. It just takes time— and the tenacity of journalists and of other lawmakers. A prediction: starting soon, even aboveboard administration officials will begin to disappear. My money would be on Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld and C.I.A. director George Tenet. President Bush's "true friend" British prime minister Tony Blair will likely go first, though. Whatever genuine corruption there may be within the administration may take longer to detect and bring to ground.

A11 of those in the government should heed one of the great political scandals of the last century, Teapot Dome. Albert B. Fall, who was appointed secretary of the interior under Warren G. Harding in 1921, decided to lease out oil reserves in California and Wyoming, which had been kept for naval use. One was called Teapot Dome and the other Elk Hills. Drilling rights to both sites were awarded to big-oil interests. Fall subsequently received gifts and loans totaling $400,000 from the owners of those companies. The Senate authorized an investigation, and Calvin Coolidge, Harding's successor, appointed special prosecutors to the case. It took years, but the Supreme Court finally invalidated the leases and Fall was found guilty in 1929 of accepting a bribe. He was forced to pay $100,000 and ended up spending nine months in jail. Democrats being Democrats, they were unable to capitalize on the Republican scandal, and lost both the 1924 and 1928 presidential elections. Some things never change.

GRAYDON CARTER

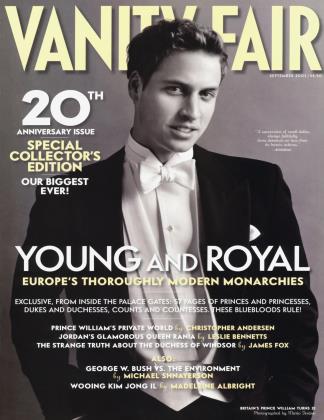

FOR COVER DETAILS, SEE CREDITS PAGE

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now