Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

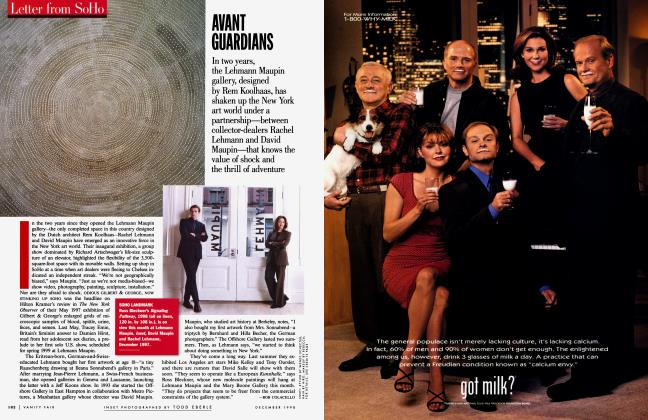

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowAttending the sentencings of Martha Stewart and Peter Bacanovic—and remembering his own, misleading first encounter with Martha—the author predicts a comeback for the domestic-arts tycoon, with a second act in L.A. for her ex-broker. Plus: the New York jitters and Ron Reagan Jr., Democratic-convention star

October 2004 Dominick Dunne Jessica Craig-MartinAttending the sentencings of Martha Stewart and Peter Bacanovic—and remembering his own, misleading first encounter with Martha—the author predicts a comeback for the domestic-arts tycoon, with a second act in L.A. for her ex-broker. Plus: the New York jitters and Ron Reagan Jr., Democratic-convention star

October 2004 Dominick Dunne Jessica Craig-MartinOn August 2, I attended the party to celebrate the publication of American Soldier, the memoir of General Tommy Franks, hosted by V.F.'s Graydon Carter and Judith Regan, head of Regan Books. It wasn't the usual New York book party, where several hundred people are jam-packed into a restaurant or private club. This party took place during a gorgeous sunset on the deck of the Intrepid, the aircraft carrier permanently docked in the Hudson River as a museum at 12th Avenue and 46th Street. We had a whole new view of the New York skyline with a summer wind at our backs. It was a magnificent feeling after an upsetting day. My New York apartment happens to be five blocks from the CitiGroup Center, on Lexington Avenue at 54th Street, one of the financial targets located in New York, Newark, and Washington, D.C., that al-Qaeda apparently has plans to blow up, or so Secretary of Homeland Security Tom Ridge had warned us the previous day with intelligence that was several years old but that was nevertheless being taken very seriously. "Al-Qaeda plans far ahead," I heard someone say on television. Walking past CitiGroup is part of my daily routine in New York, and that day I was stunned to see the amount of security deployed outside the building. I felt as if I were watching another city in another country, not my familiar neighborhood. I saw heavily armed soldiers, riot gear, truck blockades, bomb-sniffing dogs, and newly erected concrete barriers. People on the street were meeting one another's eyes the same way they had on that terrible morning of 9/11. Standing on the deck of the Intrepid, I related all of this to Matt Tyrnauer, a fellow writer for this magazine, and he said, "It could be a diversionary tactic to get all the resistance in one place and then bomb another." I guess that is what our thinking and our lives are going to be like for the foreseeable future. The threat of terror has become part of our daily fears. I have gotten so paranoid on the subject that I find myself suspecting those taxi drivers who never stop talking on their cell phones of making nefarious plans to attack the city I love. What a different world we are living in.

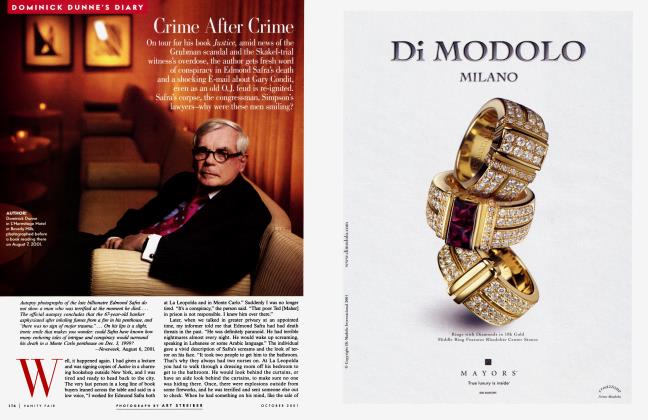

On the morning of July 16, after two postponements, Martha Stewart was sentenced in a courtroom at 40 Centre Street in Manhattan, and her former broker, Peter Bacanovic, was sentenced that afternoon. I was present at both court sessions. Bacanovic, who had played only a supporting role at the far end of the defense table during the trial, had objected to having his sentencing also lumped in with Stewart's. There are resentments between them. In both cases, the procedure was over quickly. In neither case was it as dramatic as the moment they had been found guilty, on March 5, when some people wept openly in the courtroom while others exulted.

For the prosecution, it was a tarnished victory. Lead prosecutor Karen Patton Seymour had told the jurors in her opening statement, "This is a case about lying." But after the guilty verdicts were delivered, it came to light that Juror No. 8, Chappell Hartridge, who had made no secret of his distaste for Martha Stewart, had lied, too, concerning his prior-arrest record in order to get on the jury. Worse yet, Larry Stewart, an ink expert who had been called as a prosecution witness, is accused of lying during his testimony, for which he was subsequently indicted. Both times Stewart's lawyer Robert Morvillo requested a new trial, and both times Judge Miriam Goldman Cedarbaum turned him down.

He objected to having his sentencing lumped with Martha's.

I was one of many who had kept hoping that Stewart would not have to go to prison, feeling that her enormous skills in domestic science could be put to good use in public service for the unfortunate women of New York. But it was not to be. I'm also a big fan of Judge Cedarbaum's. Throughout the trial she was very fair, and to my mind she consistently made the right calls. The judge gave both Martha Stewart and Peter Bacanovic the minimum sentence of five months in prison, followed by five months of house arrest, plus two years of probation, and a fine—$30,000 for her and $4,000 for him. Because they could have received sentences of 12 to 16 months in prison, the consensus was that the judge had been generous and let them off lightly. Of course, that's easy to say. Being locked in a prison for even five months has to be a terrifying prospect. I've been on two television shows with Susan McDougal, who did 18 months in prison for the admirable and heroic stance she took to defend Bill Clinton, and her stories of the indignities women suffer in penal institutions in this country are not pretty. Stewart chose her house in Bedford, New York, which is still under construction, to serve out the second five months of her sentence. Judge Cedarbaum told her that she would be allowed to leave the estate for up to 48 hours each week for work, grocery shopping, religious services, and medical appointments. She instructed her that she could have only one telephone, and it could not have caller ID, call waiting, or call forwarding. She also told her that she could not go online on her computer.

For all those Martha-knockers out there who find her too arrogant for words, I think it's a pity that her statement to the court after her sentencing wasn't televised. It was not dictated by lawyers and it was not a public-relations pitch. It was Martha from the heart. "Today is a shameful day," she began. I'm not going to tell you that she cried when she read it. She didn't. But she was close to tears. There was a break in her voice and a hesitancy in her words, but she persevered bravely. I was touched by her delivery, though I must confess that I wish she hadn't referred to her long ordeal with the law as "a small personal matter," since the consequences of that matter have proved to be so devastating for so many people, including her employees and her shareholders. She left the courtroom with dignity, stopping along the way to speak to friends and nodding politely to the guards. She was classy. Fifteen minutes later, however, on the steps of the courthouse in front of the television cameras, she gave a much more strident version of the statement, this time with defiance in her tone and a plug for her magazine. Immediately after that, she went for an interview with Barbara Walters, a tape of which was played on ABC that evening. I liked the way she admitted having been hurt by some of the things that had been said about her. I liked the way she said the words all the newspapers later picked up on: "I'll be back!" She will. I have no doubt of it.

There are no two ways about it— to a lot of people Martha Stewart is a hard sell, and I understand why. Years ago, when I first knew her, we had the same publisher, Crown, and the same publicist, Susan Magrino, who was a great friend of both of ours and who brought us together. In one early conversation with Martha, I happened to mention that I had a house in Lyme, Connecticut, and she went into such a diatribe on the subject of Lyme disease that she made me feel all but responsible for the epidemic. In time I got past that off-putting quality of hers and came to know her as the amazing woman she is. I find her totally fascinating and utterly true to herself, whether she's right or wrong. I have an image of her that I'm sure I'm going to recall when she's doing time. One night at her house in Seal Harbor, Maine, which used to belong to the Edsel Ford family, she decided on the spur of the moment to take her guests for dinner to a lobster shanty on a nearby island. We piled into a couple of cars and drove down to a dock, where we boarded a large speedboat. There were about eight of us. I kept looking around for the captain until I realized that, of course, Martha was the captain. It was the blackest of nights, and the Atlantic was rough, and you couldn't see a foot in front of you, so I was a bit nervous. But there was Martha at the wheel, master and commander, racing that boat through the darkness, and I just knew that when we landed, safe and sound, a wonderful lobster dinner would be waiting, and all the student summer help would be lining up to worship her.

Peter Bacanovic's life in the financial world is irretrievably over. But Peter, whom I know personally, is not over by any means. It's well known that he is a highly social and very popular figure in New York, a friend in good standing with a great many people, many of them very important people. They admire him for taking his punishment and never "ratting out" his former client, which was certainly an available option for him. I observed a smattering of his friends in the courtroom the afternoon he was sentenced. Somehow he knew his sentence before Judge Cedarbaum read it to him. The previous day, there had been a picture of him in the New York Post, which quoted him as saying to a friend he passed in the street that he would get five months in prison and five months of house arrest.

His mother wept. His dignified father looked crushed. Peter hugged a few people. He had dinner that night with his family and 15 close friends who had stood by him through the long struggle. Then, after meeting with his parole officer, he left New York for California. Since his indictment in June 2003, he has been spending more and more time on the West Coast. He has made many friends there and already travels in the social and movie circles. I feel sure that he will head for Los Angeles after his incarceration. In my Hollywood novel, An Inconvenient Woman, I have a character named Casper Stieglitz, a former producer fallen on hard times, who says, "Hollywood will forgive you, even overlook, your forgeries, your embezzlements, and, occasionally, your murders, but it will not forgive you your failure." Peter Bacanovic is never going to be a failure, and his five months in the clink are not going to stop people from asking him to dinner. He's very ambitious and extremely likable. Several of his friends speculate that he might become an actor's agent. I can see him turning out to be an enormous success, representing gorgeous movie stars and squiring Nicole, or Gwyneth, or Halle, to the premieres of their new pictures.

Ron's eulogy was endearing but also edgy and provocative.

At Martha Stewart's morning sentencing I observed her new appeals attorney, Walter Dellinger, former acting solicitor general in the Clinton administration. He's among the best in the business. I talked to him in the greenroom of a television show where we were guests in different segments, and he said he felt passionately that Martha's sentence would be overturned on appeal. Maybe it could be, but the process would probably take a year. Having an unpleasant legal matter hanging over your head like a dark cloud is a very stressful way to live. If the guilty verdict were overturned, there would likely be another trial, and we all know how unpredictable juries can be.

Ann E. Armstrong, Martha Stewart's loyal assistant, who wept on the stand before reluctantly testifying as a witness for the prosecution that Martha had altered and then changed back an e-mail from Peter Bacanovic, left her employ after the trial. Annie, as she is known, is said to have hated the publicity, and she was apparently crushed that her testimony proved to be so damaging. The other person who caused a sensation at the trial was Douglas Faneuil, Peter Bacanovic's young assistant, who had made the phone call to Stewart telling her that Sam Waksal and his family were dumping their ImClone stock. After initially going along with Stewart and Bacanovic, he eventually reversed himself and became a prosecution witness. As much as I was rooting for Martha and Peter, I always felt rather sorry for Faneuil. He was, after all, hired help, taking his orders from important people, and he got caught in the vortex. From the advance word on him, I had expected him to be a sleazeball, but he wasn't. Just 28 years old, he was cross-examined by some of the best lawyers in New York, and he held his own. I was not present when he reported to Judge Cedarbaum a week after Stewart and Bacanovic were sentenced. He apologized for having originally helped to cover up the sale of Martha's stock. He could have been sentenced to six months in jail, but Judge Cedarbaum allowed him to walk away with a $2,000 fine and no probation. "You are in every way a very lucky young man.... I hope that my reliance is well placed, and if it is, I wish you good luck." See what I mean about Judge Cedarbaum?

I'm always fascinated to watch people come into their own. We recently witnessed such a phenomenon on the national scene when Ron Reagan Jr., who had been practically out of sight since his days as a dancer with the Joffrey Ballet during his father's presidency, stepped forward to take a place in the public arena. If President Reagan hadn't died when he did, Ron would probably never have been asked to address the Democratic National Convention in Boston. It's as if his dying father handed him his big moment and the son grabbed it and ran with it. For the five days of the presidential funeral, he was constantly on television as the devoted son of his mother, Nancy, with whom he had experienced long periods of estrangement over the years before they were brought together again in the late stages of the former president's illness. His sunset eulogy at the Reagan library, in Simi Valley, was endearing regarding his father, but it was also edgy and provocative and even a little rude in its references to President Bush and Vice President Cheney, who had earlier in the day provided the Reagan family with the most spectacular Washington funeral in 30 years. I thought his plea for stem-cell research at the convention was stunning, instructive, and at times passionate, reinforced by the knowledge he had acquired from his father's 10-year battle with Alzheimer's disease. Watching Ron handle himself so well at the podium, I kept thinking about his mother and the complicated position his speech put her in. She agrees with her son word for word on what he said—she has made that known in the past—but she is also a Republican through and through, as well as the recent widow of one of the most popular Republican presidents in U.S. history. How odd it must have been for her to watch her son address a national convention of Democrats and bring down the house.

Ron Reagan's speech was so effective that First Lady Laura Bush, whose father also had Alzheimer's, felt obliged to give him a slap in the face when she told an audience in Royal Oak, Michigan, "I know that embryonic-stem-cell research is very preliminary right now, and the implication that cures for Alzheimer's are around the corner is just not right and it's really not fair to people who are watching a loved one suffer with this disease."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now