Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowConcocting perfumes and creams in her London walk-up, Jo Malone broke all the rules of scent (coffee and lilies?) to create a must-have luxury for royals, stars, and supermodels. After a battle with breast cancer, and backed by Estée Lauder, the darling of the $1 billion fragrance industry is going global

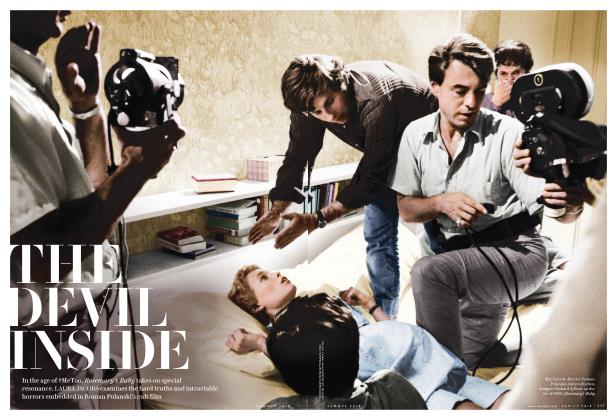

December 2004 Laura Jacobs Hugh StewartConcocting perfumes and creams in her London walk-up, Jo Malone broke all the rules of scent (coffee and lilies?) to create a must-have luxury for royals, stars, and supermodels. After a battle with breast cancer, and backed by Estée Lauder, the darling of the $1 billion fragrance industry is going global

December 2004 Laura Jacobs Hugh StewartJo Malone was born with a nose. Her early memories are snapshots in scent. Father: linseed oil on a paint palette, the starch of his crisp white shirts. Mother: Je Reviens perfume, Christian Dior's Diorissimo. Warmth: the family Labrador, biscuity in the sun. Happiness: hyacinths at Christmas. In fact, as a child she could tell time by the scent in the air—she had to: she was dyslexic and couldn't read a clock. For Jo Malone, smell is "a tune that hums not in my head but in my nose."

A portrait of the artist as a young woman? Or a portrait of the entrepreneur?

We all know fragrance is a short circuit to limbic stirrings: loves, needs, ideals, things that go bump in the heart. It is also a billion-dollar business. Just look at the annual hatching of heightened moments—the captures, raptures, eternities, infinities—all incubated by committees in a lab, then sold in million-dollar ad campaigns. What if there was a nose in the kitchen mixing not heightened states but Proustian interludes, the kind of scent blendings that happen under the sun, at the vegetable stand, on vacation, while horseback riding in the rain? Potent notes coaxed into poignant combinations, then presented like gifts from the Magi. Amber & Lavender. Wild Fig & Cassis. Lime Basil & Mandarin. Could you build a fragrance empire that wasn't selling a designer identity, wasn't about the model in the ad, wasn't a game of semantics at all, but was instead a matter of poetics, "petals on a wet, black bough," an exploration of the way scent plays—top note, middle note, base note—on the skin and in one's life? "I love when scents slightly collide with one another," says Jo Malone, "and finding a way to lock them together and move them as one." The company that began in 1994 as a tiny London shop at 154 Walton Street—and not a pence spent on advertising—is now, 10 years later, Jo Malone London, the most exciting fragrance concern in the world and an empire about to go global. Think Emily Dickinson meets Estée Lauder.

Nose aside, it couldn't have happened without the hands, inherited from Mum. Jo—actually Joanne—was born to Eileen and Andy Malone in 1963. Eileen was a respected aesthetician with "amazing hands," heir apparent in the clinic of Countess Lubatti, a skin-care guru who practiced an age-old method of facial massage—the art of lymphatic drainage. Flamboyantly distilled, Lubatti accessorized her white lab coat with white fishnets, set off her snow-white hair with blood-red lips. She mixed her own creams, masks, and healing potions as well as her own past, for truth be told she was a fake countess, and her stories of jade baths in China, diamonds in India, were as questionable as they were wonderful. But the facials, the creams, were true. Through the 50s and 60s, Lubatti had a devoted upper-crust following.

The Jo Malone facial is a 75-minute treatment that has the floating pace of a tea ceremony, the calibrated pressures and curls of calligraphy.

'There were two great women," says Jo, "Countess Jacki and Countess Lubatti, and that was where all of London went."

Little Jo went, too, because the Malones couldn't afford a nanny. While her mother gave facials, Jo sat on a stool in Lubatti's lab and watched. "She was incredibly strict, and I never wanted to upset her, because I had seen her get cross. 'Don't touch anything, Jo.' 'No, I won't.'" A vocabulary accrued: crystallized camphor, slippery elm, mortar, pestle, the names of endless herbs in endless jars, face creams setting in the fridge. By the age of seven, Jo was allowed to touch, "drying the sandalwood and straining the juniper." At home, she shaved Camay with a cheese grater—"I got in trouble for that"—boiling it into an oil base for soaps she made as gifts.

Jo's dad, Andy, also worked with his hands. Having started his career as one of the Queen's architects, a job that entailed looking after protected buildings, he eventually concentrated on his art—marine watercolors, renderings of historic ships—which he sold in the local market. Not the steadiest income.

"I used to get up at an ungodly hour," remembers Jo, "go and set the stall up, put our merchandise out. He's hopeless with money, my dad, a typical artist, so I would send him off to get breakfast and I would stand, and I learned from a very young age that telling stories sells product. I was seven, eight, and I would take all the prices off, because Dad would always underprice, and I'd tell stories. That's how I would sell them."

She had good reason to stand and sell. A recurring theme in the Malone home was Eileen's matter-of-fact reminder "We have to earn some money today, otherwise we cannot pay the bills." Everyone pulled their weight, and the Malone family, which now included younger sister Tracey, was a four-man tag team in their government-funded, two-up two-down council house, in Bexleyheath, a suburb of London.

"I would come home from school," says Jo, "and Mum would come home from work. And she would need her sheets from the clinic washed, so 10 o'clock at night I would be standing there washing the sheets and ironing them. We worked incredibly hard. But I've never felt as though I hadn't lived like a king. I've known what it is to have nothing, but if you had a side of roast beef on a Sunday night, that was living like a king. And Christmas was always an amazing time in our family. They really would push the boat up and make it very special. We always had the best they could give us."

That was the message: Give your best.

"I know you'll be successful in whatever you do," Lubatti once said to young Jo. "But remember, just remember, whenever you do something, do one thing that really matters and do it beautifully. No one will ever remember you for doing too many things half well."

Jo left school at 16. Her mother had inherited the late Lubatti's clientele and, having separated from Andy, was giving facials in a small apartment in Kensington. Still, Eileen's health wasn't so good, and, as ever, "we have to earn some money today." So Jo, with a teacher's parting words in her ears—"Jo Malone, you will never make anything of your life"—took a job at one of London's top florists, Pulbrook & Gould.

"I loved it," says Jo. "I loved the smell as you cut the stems, that green fresh note. I learned the names of flowers. I would memorize them. I could name every lily. It was magical." It was also a measly £29 a week, not even a living wage. So at night Jo did window boxes, washed dishes at dinner parties, anything. Eighteen months of Eden ended when Eileen Malone had to be hospitalized. With Tracey in school and Eileen needing nursing, Jo took over her mother's clientele.

"I'd watched for years and years and years," says Jo. At the Kensington apartment she'd begun working with her mum, "doing people's feet. I massaged feet and hands and arms. I mean, I'd grown up with these women around me."

Until Eileen was well enough to work again, the business was in Jo's hands, which turned out to be as amazing as her mother's—empathic, with a listening touch and a strong energy. At 18, Jo was doing what fate seemed to want her to do, taking Lubatti's techniques into the next generation, mastering the dance, improving it. At 19, with Mum on her feet again, Jo went out on her own and took the Jo Malone facial with her, a 75-minute treatment that has the floating pace of a tea ceremony, the calibrated pressures and curls of calligraphy. From 20 inherited clients Jo would grow a new list. Word of mouth brought younger bluebloods, fresh celebrities, into her hands. She was mixing her own creams and potions, instinct telling her what to add and when it was right. The pixie blonde with unblinking blue-green eyes was toting her massage table to clients' homes, lugging creams and sheets around London, booked from dawn till dusk. And still, the girl who "did faces," living hand to mouth despite her well-heeled clients, had more to give. "To this day I believe that what you get out of life you must put back." Jo signed up for a class at London Bible College, a two-year course, three nights a week. The focus was troubled youths and how to help them.

'She was drop-dead gorgeous," says Gary Willcox, a looker himself, with blue eyes as direct as Jo's. "The two of us were there because we wanted to know more. I suppose back then we didn't have such privileged lives, and yet still there was something we could give. She's got a great heart. And she's got great ears, not ears that you could whisper something in and she picks it up, but more so the words you don't say. She understands people. There's great sensibility about her."

From their first date—swimming and then a walk on Wimbledon Common—Jo knew she'd marry Gary. "I just loved his spirit." Wilcox was a surveyor for a building contractor, but he was considering becoming pastor of a church, which is why he went to London Bible College. "He was funny," says Jo, "and he was smart and sensitive. He asked me to marry him and then changed his mind twice."

Gary explains: "For me it was, This is for life. I've got to get it right. That's why I asked her three times." The third time, Gary asked if there was any chance. "Absolutely not," Jo answered.

"I remember the smell of his leather jacket, and the smell of his cologne—I mean, I was absolutely besotted," she says. "I knew I'd say yes, but I felt, You ain't getting off the hook. So three hours later I said, 'Well, you still haven't got down on your knee.'" At the wedding, in 1985—over the protests of friends and family, who said, "You'll never stay married, you're far too young, it'll never work"—Jo said yes for the fourth time.

It did work, in the way marriages do when husband and wife are also best friends. Gary saw that Jo was reaching a turning point in her life. She needed ... something. "He said to me, 'Why don't you take six months? We can survive that. I can support you.'" Jo had never been supported in her adult life and really didn't want to start. So he suggested they find a better apartment, a home base she could work from. He took her to see a one-bedroom off Walton Street—small, yes, but in fashionable Chelsea and washed with light. "I walked through that door," says Jo. "I knew. I knew it was the beginning." Perhaps she could smell it: roots.

Three flights up, in sparsely furnished off-white rooms, Jo Malone was elevated to "best-kept secret" of royals and rock stars, society dames and top models—a hush-hush Who's Who that has included Queen Noor and her late husband, the King of Jordan. Jo's cleansers and creams, which one could get only from her, were achieving cult status, reaching the likes of Serena and David Linley, Yasmin Le Bon, Natasha Richardson, Elton John, Kate Moss, Katie Couric, Jennifer Lopez, Julia Roberts, Diana Ross, Barbra Streisand, Madonna, Jimmy Choo, Donatella Versace, and Salma Hayek. When the client list hit 2,000, Jo had to close her book, making her even more exclusive. "People used to beg on the telephone," says Ruth Kennedy, managing director of Linley, the bespoke furniture company, and a good friend. "She was doing between 8 and 10 clients a day. And there were people—she won't tell you this, but there were people who flew to London to have her do their face."

As a child, Jo Malone could tell time by the scent in the air.... For Jo, smell is "a tune that hums not in my head but in my nose."

So while the hefty Chelsea rent was a stress, Jo says, "by Tuesday, Wednesday, I'd already got my rent, I can eat. What else can I do?" Again, she knew. Haunted by scent, by combinations that stopped her in the street, she began to play with fragrance.

"I could smell things in my head, but I didn't know how to physically make it happen." She and Gary still needed a proper bed (they had a foam mattress on the floor), still needed curtains for the windows (they undressed in the dark), were still eating canned tuna for dinner (or sharing one crepe on evenings out). Money saved, however, had a way of taking itself to Grasse, to Paris, where Jo went to learn the industry, a day here, three days there. "This British girl," she says, "banging on this wonderful perfumer's door"—Jean Louis, one of the old-world noses who helped Jo when others were saying, "No, you can't do that, you can't put those notes together."

"Why not?" wondered Jo. "Who says?"

Every great business success can be distilled to its pinch of can-do DNA, the spring at the center of an ever widening circle. For Jo it was Nutmeg & Ginger, unheard-of seasonings in a sandalwood-and-cedarwood base. She'd done a wild-strawberry note. She'd done a violet note. But they weren't right, because they weren't her. She wanted character, the collision, strong notes raw and rich and moving "as one." Strangely, Nutmeg & Ginger, Jo's first fragrance, is the only one she can't trace to a moment or memory. The best-selling Lime Basil & Mandarin would be spurred by a trip to the Caribbean—Gauguin greens flushed with citrus. French Lime Blossom is Paris, inspired by Toulouse-Lautrec paintings ("I began translating the characters into fragrance in my head") and a walk on the Champs-Élysées, linden above and tarragon floating off tables. A stay at the Hotel Bel-Air triggered Orange Blossom, a delicious ingenue. And brooding, velvety Black Vetyver Café, another "It'll never work" combo, three years in the making, was a plunging epiphany at Dean & DeLuca; Persephone in the underworld, a barrel of bitter dark coffee beans next to a bucket of full-blown Casablanca Lilies. (When Jo lowered her head to the coffee a woman next to her said, "Smells like a Jo Malone fragrance, doesn't it?") But Nutmeg & Ginger— where the idea came from Jo doesn't know. Artists often don't know, they just grab on for the ride. "I knew it was a winner," she says. (Lightbulb: it's a self-portrait—Jo's warmth, strength, and spark in scent.)

Jo had no intention of selling the fragrance. Indeed, she could produce it only as a bath oil because she didn't have an alcohol license. The year was 1987, and in continuing gratitude to her clients Jo gave a thank-you bottle to everyone. "People started saying, Jo, this is the most amazing stuff. Can I get some of it? Well, have another bottle. Then one woman one day said to me, 'I want to buy 100 bottles.' That night Gary said, 6 How many bottles?' She had a dinner and put it at the place settings of her guests. They were very influential people—and 86 out of 100 wanted to purchase more of that product. And that was the start." The business exploded, word of mouth spreading like wildfire.

"I was at EMI," says Amanda Kyme, a close friend of Jo's and today an associate director at the PR. company Halpern. "I worked in artist relations, so I had to do an awful lot of gift buying, birthdays, welcome-to-London gifts, and we were always looking for something new, exclusive, and it's got to be something pretty luxurious and exciting when you're dealing with A-list celebrities and artists. At this point it was still in her apartment, it was so exclusive, but we always had people say, 'Where can I get more of this?'"

Jo and Gary still worked their day jobs, but into the wee hours they were boiling, mixing, stirring, bottling, labeling, and packaging bath oils and skin-care products in their minuscule kitchen—hundreds of bottles a night. Come Christmas, Jo and Gary found themselves looking at thousands of orders and mixing bigger batches. (Gary: "How many drops?" Jo: "I don't know how many drops ... until it smells of rose.") Jo loved the business as it was. She liked the cosseted, drawing-room world she'd created. "I felt safe," she says. "I would run around in my little white coat, my little black skirt, exactly as the girls are now." But Gary was tired. Though they'd upgraded to a sofa bed, he wasn't in it till three, and then was up by six. With Christmas of '92 upon them, orders flooding in, he saw the turning point Jo refused to see, and said, "I can't do this anymore." He told her they needed a shop. He said that they could work together, that he'd like to have the job if she got someone else to interview him. If it didn't work, he could always go back to contracting. In short, Jo says, "he came on as managing director and he changed the course of the business."

That first Jo Malone store set the tone. Modeled on a French perfumers studio ... it suggested an apothecary in heaven.

Is there a better omen for a retail debut than getting a million-pound offer for your company the day the door opens? And happily turning it down? Clear and coherent from the ground up, with Jo as the creative right brain and Gary the analytical left, Jo Malone opened in October of 1994, a jewel-box boutique on Walton Street with nine fragrances to its name. Simple, pristine, distinctive, clean—these are the words one hears repeatedly when the subject is Jo Malone. That first store set the tone. Modeled on a French perfumer's studio, its slim rectilinear bottles lined up in martial rows, crystal stoppers and silver caps agleam, it suggested an apothecary in heaven. The palette was cream-on-cream, and the only other color was that of the elixirs themselves— pale golds, pale pinks, pale greens. The cream-and-black packaging—a warm lemony cream (it's on the walls in every store, and in Jo and Gary's flat) and a masculine matte black—was designed to transcend gender. And the philosophy behind the creation of the fragrances—Why not? Who says?—was the philosophy in the store: play with the notes, layer them, find yourself in interesting collisions, for instance, the blush of Red Roses over earthy Wild Fig & Cassis. It was a bespoke approach, a Savile Row of scent, and it had customers buying two, even three, fragrances at a time.

And it was hands-on, just like Jo and her famous facial (now available in New York as well as London); just like the fragrances she mixed with eyedroppers to her own passionate standard ("You have 100 percent of me in every single one of them"); just like the store, with its sci-fi scent booth, where you press a button and fragrance puffs into the air, and the new Skin Care Bar, a coffee-bar approach to Jo Malone, where one can experience a free hand-and-arm massage that is also a lesson in how to use the products. Nothing was pre-packaged in cellophane. Every purchase was wrapped in the best black tissue, placed in that beautiful cream box, tied with a black grosgrain ribbon, slipped into a matching cream bag, and tied with another black bow. It was scrumptious, scrupulous, and it hit the industry full sail.

"We were immediately enchanted with the world of Jo Malone," remembers Rose Marie Bravo, then president of Saks Fifth Avenue, now chief executive at Burberry. "The wide range of fragrances that she offered all at once, people had done that before, but nobody in such a classy way, each fragrance seemingly so pure and so focused on their ingredients, and the different body creams, body lotions, user-friendly in every way. And you're seeing this magnificent packaging. Beyond what the price might be, you want to buy into her world. That's what reminds me of the Tiffany experience. She understood cosmetics as a gift. And I don't think that's ever been done before."

"Right," says Steven Horn, director of retail for Swiss Army Brands, and a friend. "It became the best gift to get and to give. She wants everybody's life to be touched and enriched because of the power of fragrance."

Jo and Gary had manufactured enough products for two years, or so they thought. Within six weeks of opening, much of their inventory was sold out. By Christmas the company was breaking even and breaking rank: in London, a city that doesn't do queues, the lines at Jo Malone stretched round the block. By spring the business had a loyal following: 72 percent of its customers were repeat purchasers. In 1997 the shop grossed $2 million; in the next two years net sales would grow fourfold. In 1998, in a pioneering move to prove itself in America, Jo Malone opened a counter at New York's Bergdorf Goodman: three months of stock sold out in two days. And still, not a penny spent on advertising. None of this was lost on one of the most powerful men in the industry, Leonard A. Lauder, of the Estée Lauder Companies Inc.

"I have always been interested in young ambitious women who wanted to strive to get to the top," says Lauder. "And one of our executives said, 'You know, there's this company in London named Jo Malone and they seem to be doing great things.' We went into the shop and both of us came to the same conclusion immediately: something's happening here."

When Lauder met Jo, he saw "her spark, her style, her ambition, the light in her eyes, the lilt to her head—everything. There was a drive to succeed, to do well, to have great products, that I had not seen for a long time, and I was enchanted."

From a corporate standpoint, Estée Lauder wanted to increase its offerings in upscale department and specialty stores. "Jo Malone fit right in with that," says Lauder, "very niche, upper niche. They don't try to be mainstream, they don't try to get big rankings, they just go on and on being the very, very best at what they do." It didn't hurt that Lauder's wife, Evelyn, bought Jo Malone products. "If it's good enough for her to buy," he says, "it's good enough for our customers."

"I am secretly in love with him, I think," Jo says of Lauder. "I met him and I saw eyes that I knew so well. He's been where we've been."

Still, the decision to sell had to do with where they were going. "We couldn't do all we needed to do," Jo told the Financial Times. "We couldn't open another store and put money into developing products unless we borrowed money, and I wasn't prepared to do that." In 1999, Lauder told Jo and Gary what they needed to hear: "I know you can do this on your own, but we can make it happen faster." Forty-eight hours after the deal was done, a sale rumored to be about $9 million, Jo was in Estée Lauder's New Jersey labs expanding her skin-care line. In 2001 an American flagship opened in Manhattan's landmark Flatiron Building, and shops will soon grace Australia and France. "On paper I don't own one share anymore," says Jo, who remains chairman to Gary's managing director, "but in heart and soul it is 100 percent mine."

Today, heart and soul are very much on Jo Malone's mind. She, Gary, and their three-year-old son, Josh, recently returned to London after having spent a year in America, and not on business. In the early summer of 2003, at 39, Jo discovered a lump in her breast. Lying on the exam table, getting it checked, "I saw people's faces and suddenly thought, Oh my God. I said, 'Have I got cancer?"' She did.

"And my first thought was I can't leave my boys—my son, my husband." Late that night Jo called Evelyn Lauder. "I said, 'I'm going to die,' and she said to me, you ain't gonna die. You're going to see your son grow up." Three days later, Jo was at New York City's Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center. She told her doctor, "Do whatever you have to do to keep me alive." And he did.

"I had one mastectomy because I had to," Jo says, "and then I made the decision to have a prophylactic mastectomy as well." Because her system is so sensitive—the price for that creational nose— she could not take painkillers, which made the year doubly tough. "Going through chemo, it's very hard. But I would will myself through the day."

"She was a rock," says Leonard Lauder. "I never saw her when she didn't have a smile on her face, wasn't positive."

"And Gary," says Steven Horn, "he handled that brilliantly. They weathered that storm like they weather every single thing in life. They were together, they were a team."

"I knew I would reach a day like this," Jo says, "because of my team. Because of these incredible people who stand by you and will you through it. And my friends who held me together."

When Leonard Lauder met Jo, he saw "her spark, her style, her ambition, the light in her eyes, the lilt to her head-even thing.

"A day like this" is a bright, blue London morning in July. Jo isn't thrilled with her hair, which came in gray, is now light brown (short like Joan of Arc), and won't be dyeable to blond for some time. She's still a bit swollen from the reconstructive surgery. (Notices went out: "Gary and Jo are pleased to announce the arrival of two bouncing girls.") But in every other way Jo Malone is soaring, so happy to be home, to be back in the large, airy apartment she and Gary moved into while she was pregnant with Josh; back to sleeping in her own bed upstairs (yes, they finally got a real bed); back to her home team, who not only maintained the company while she and Gary were away but grew it (Jo: "very humbling experience, that"); back to having her nose again, which she lost temporarily during chemo; and back to the morning ritual of sitting in her living room of ivory, cream, and beech, sniffing mixtures from chestnut-brown bottles.

And then again, not exactly back, but, rather, changed. She talks of moving beyond her signature calm of creams and beech, of wanting color—mulberry purple! pistachio green!—and vibrancy. (Jo shocked the household when she brought sunflower marigolds into the white-flowers-only flat.) She's getting ready for the lOth-anniversary launch of Vintage Gardenia, another winner. "After completing it I knew I was back on. But it's different. I wanted something new, which is the cardamom. But I used all vetivers, ambers, gardenias, tea roses, my most favorite things over the last 25 years."

"Jo's got lots of ideas," says Gary, "about what she'd like to do going forward, as a result of going through the experience she has. There's a greater sense of what is important and what isn't."

"I feel this incredible life force," Jo says. "It's just this: I'm not frightened to do anything, to try anything, because what have you got to lose? I feel that I have something that is a natural ability. You have to work at that. You can't take it for granted. I feel I have been given a gift."

And isn't that what it's all about? Using, loving, the gift.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now