Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

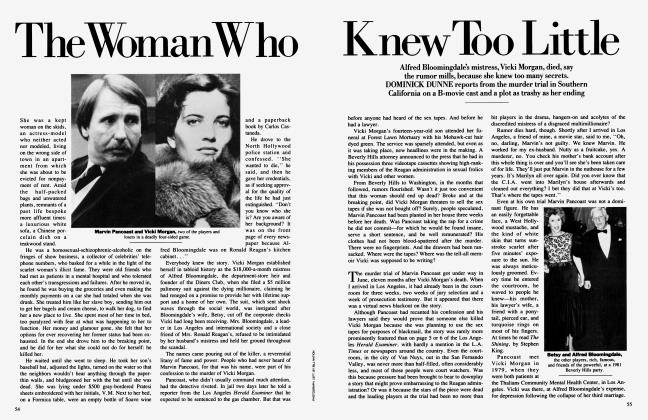

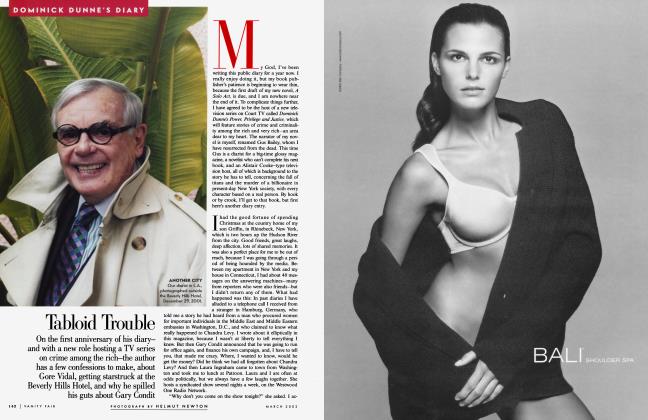

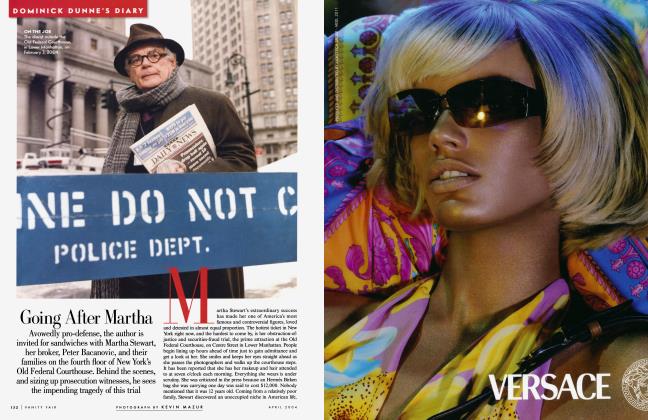

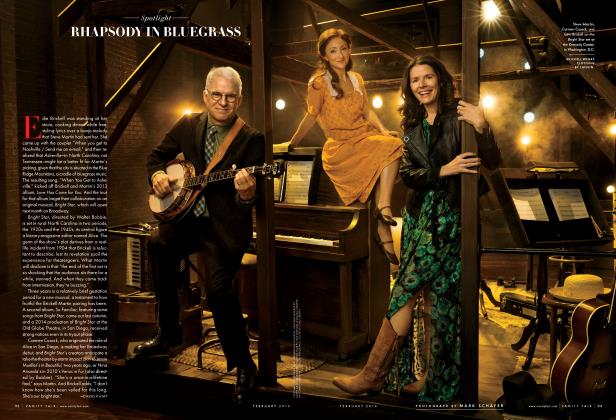

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowWhile sussing out the Skakel-appeal strategy and a new wrinkle in the Sansum case, the author attends memorials for the American icons George Plimpton and Eleanor Lambert, and learns that he's persona non grata in Monaco

February 2004 Dominick Dunne Mark SchäferWhile sussing out the Skakel-appeal strategy and a new wrinkle in the Sansum case, the author attends memorials for the American icons George Plimpton and Eleanor Lambert, and learns that he's persona non grata in Monaco

February 2004 Dominick Dunne Mark SchäferMichael Skakel's new attorneys, Hope Seeley and Hubert Santos, have filed an appeal to overturn his murder conviction on multiple grounds. In June 2002, Skakel, an heir to a carbon fortune and a nephew of Ethel Kennedy's, was sentenced to 20 years in prison for the murder of 15-year-old Martha Moxley, who was beaten to death with a golf club in 1975. Since the conviction, which came as a surprise to observers on both sides of the aisle in the Connecticut courtroom, Robert Kennedy Jr. has led a highly publicized campaign to undo the jury's verdict. I, among others, have been singled out for his ire. The chief argument presented by Seeley and Santos is that a 5-year statute of limitations should have barred Skakel's arrest in 2000 for a murder committed 25 years earlier. They also argue that the case should not have been transferred from juvenile court to superior court, since Skakel was 15 at the time the murder occurred—a matter already ruled on by the supreme court of the state of Connecticut. They accuse prosecutors of failing to hand over a police sketch of an early suspect. Some lawyers commenting on the case in local newspapers believe the conviction will stand, but others say the odds are that Skakel will get a new trial.

Frank Garr, the detective who has been on the case since it was reopened in 1991, and whom Skakel's lawyers want to have replaced, has this to say: "We received the brief. There is nothing in it we didn't expect. Susann Gill, a member of the prosecution team, will respond to each of those items in her brief." The supreme court of Connecticut decides when the case will be heard, which will probably be in the fall. Each side gets 30 minutes to speak. "I don't think we're going to have a new trial," says Garr.

I have learned that an online discussion site has posted the names of four people who may have allegedly helped Michael Skakel clean up the scene after the murder. Three of the names were not a surprise to me, but one of them was. Although there is no statute of limitations on murder, there is on any crime connected to a murder, such as moving a body, cleaning up blood, or getting rid of a weapon. In this case the weapon would be the handle and part of the shaft of a golf club driven through Martha Moxley's neck, which could bear fingerprints and which has never been found. The four individuals named on the Web site, even if they were shown to be connected to the crime, could no longer be held liable for aiding and abetting the killer.

Apparently I've been blackballed in Monaco. I didn't give it much thought when I was asked several months ago to be on the jury at a film festival in Monte Carlo and later told that it wouldn't work out. But recently the matter came up again, during a meeting in the power-breakfast room at the Regency Hotel, on Park Avenue. Henry Schleiff, the chairman and C.E.O. of Court TV, on which I host a series called Power, Privilege, and Justice, suggested to the executive director of the upcoming Monte Carlo Television Festival that I be a panelist in a discussion of crime coverage on television. According to Schleiff, the executive director blanched at the mention of my name and blurted out, "Perhaps Dominick Dunne is not a great idea. He may not be welcome in Monte Carlo after his coverage of the Safra case." When Henry Schleiff later told me that over lunch at Michael's, I collapsed with laughter. The death by suffocation of the billionaire Edmond Safra in his magnificent penthouse in December 1999, and the subsequent trial of his American male nurse, Ted Maher, was the biggest, most covered news story to come out of Monaco since the death of Princess Grace in an automobile crash in 1982.

It must be my age. I seem to be going to a memorial service or two a week. Both Eleanor Lambert, the fashion doyenne, and George Plimpton, the writer-adventurer, were quintessential and beloved New York figures. Eleanor Lambert's memorial was held on November 24 in the Grace Rainey Rogers Auditorium at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and George Plimpton's was held on November 18 at the Cathedral Church of St. John the Divine. Both services were packed to the rafters.

It's a wonderful thing to talk to a hundred-year-old person whose faculties have not failed. The things they know! Eleanor Lambert was such a person, and she will go down in social history as the public-relations genius who put American fashion on the map, but my connection to her had nothing to do with fashion. She knew all the fascinating people of her time, and that's where I came into the picture. She was a great storyteller, and in me she had an ever attentive ear. Once we spent a day visiting Hitler and Eva Braun's chilly aerie in Berchtesgaden, Germany. Eleanor was the perfect companion for summoning up the details of long ago. When I was writing an article for the March 1991 issue of this magazine on Lady Kenmare—the notorious Riviera socialite whose friend Somerset Maugham once playfully suggested that she may have done away with her four husbands— Eleanor, who had known her and stayed with her at her famous house in the South of France, told me, "It was Rosita Winston who got Lady Kenmare out of the country after Donald Bloomingdale overdosed on bad heroin in front of her in his apartment at the Sherry-Netherland." That event had taken place almost 50 years earlier, but Eleanor recalled it as if it had been yesterday. The last time I saw her was on her 100th birthday. Friends were having a celebration lunch for her at Swifty's, and I happened to be on the banquette at the next table. "How's your new book coming?" she asked me. She was loved in a tough business, and that love was evident until the day she died.

Lambert will go down as the P.R. genius who put American fashion on the map.

George Plimpton's death of a heart attack at 76 on September 26 came as a shock to all who knew him. Tom Brokaw of NBC Nightly News paid him a wonderful tribute on his broadcast that night. I met George Plimpton back in the 1950s. It was shortly before Christmas, and I was walking down Madison Avenue when I saw him coming up the avenue on a bike. He was already famous, so I recognized him immediately. In the basket of his bicycle were dozens of small Tiffany blue boxes tied with white ribbons—obviously Christmas presents. Suddenly he slipped or swerved, and he and the bike tipped over. The Tiffany boxes went flying in every direction as a steady stream of traffic sped by. I stopped to help him pick up the boxes while impatient taxi drivers honked at us. George was completely unruffled by the commotion he was causing, and was very courteous to me, thanking me profusely for my help. He was a true New York aristocrat, completely at home in any situation, with any group of people.

Such lions of the literary world as Norman Mailer and Peter Matthiessen ascended the pulpit in St. John's to extol their friend's madcap exploits over the years—as a circus aerialist, a boxer, a quarterback on a professional football team, a major-league pitcher, a stand-up comedian, a movie actor, a percussionist in a symphony orchestra. His Fourth of July fireworks display in East Hampton was a highly anticipated event each summer. He wrote nearly three dozen books, and he was the editor of The Paris Review from its inception in 1953 until his death. Several years ago, Plimpton and I were co-honorees at the Palm Beach Book Fair, an event that lasted several days. I never had so many laughs.

This past fall there was a new twist in the James Sansum-Helen Fioratti larceny case. Roberto Constantino of Waterford, Virginia—the son of Fioratti's brother and the grandson of the late Ruth T. Constantino, who set up the family antiques business—found fault with his aunt over the disposition of valuable furniture he had inherited on his mother's death and placed with her for resale. Constantino contacted James Sansum and let him know that he was sympathetic to him in his case. Constantino sent him a copy of a letter he had written to his aunt stating his grievances. In it he said, "I've become troubled by other consignments [my father] or I made to you, all of them. It's my suspicion ... that you've unfairly and illegally defrauded me (us) of the fair market value less commission receivable of yet another consignment we made to you in late 1996, again, from my mother's estate." The twist in the case came when Constantino also sent a copy of the letter to Robert Morgenthau, the district attorney for New York. The letter has since been made available to me. The district attorney's office called Constantino, and after a two-and-a-half-hour conversation, Constantino agreed to send additional material to Morgenthau's office.

"I really want to settle what I perceive to be an injustice to me," Constantino told me at the time. Since we talked, however, I have learned that he and Fioratti have settled the matter amicably. "She and I reached an accord," Constantino said. "She explained the basis for what she did, and I accept that."

Meanwhile, Sansum has retained as his counsel Arthur L. Aidala, who is preparing to go to trial, although he is keeping all avenues open for a plea disposition. "My client hired me because he wanted to be vindicated in a public forum," said Aidala.

In November gay activists picketed Helen Fioratti at the Connoisseur's Antiques Fair at the Lexington Avenue Armory, and they claim that they will picket every event she attends. On the New York Post's "Page Six," one of the pickets was quoted as saying, "It's really about a woman scorned. Helen groomed James and thought he would be with her forever. When he decided to go out on his own, she said it was the greatest betrayal of her life."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now