Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowBush claims to love strong women, and he is surrounded by them: his mother, Barbara, and his mother substitute, Karen Hughes; his wife, Laura, and his professional wife, Condoleezza Rice; Cabinet members Gale Norton and Elaine Chao. The only ones who don't toe the line are his daughters

July 2004 James WolcottBush claims to love strong women, and he is surrounded by them: his mother, Barbara, and his mother substitute, Karen Hughes; his wife, Laura, and his professional wife, Condoleezza Rice; Cabinet members Gale Norton and Elaine Chao. The only ones who don't toe the line are his daughters

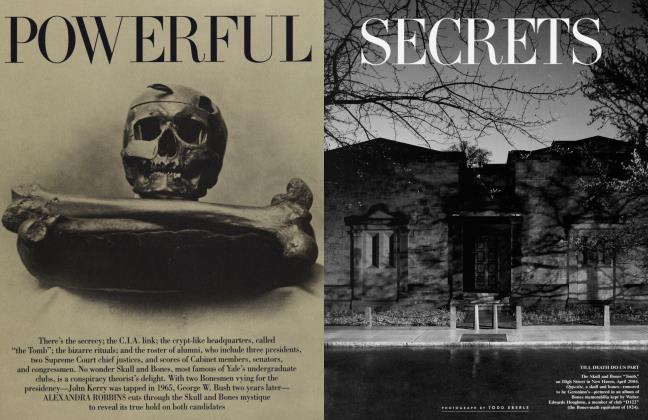

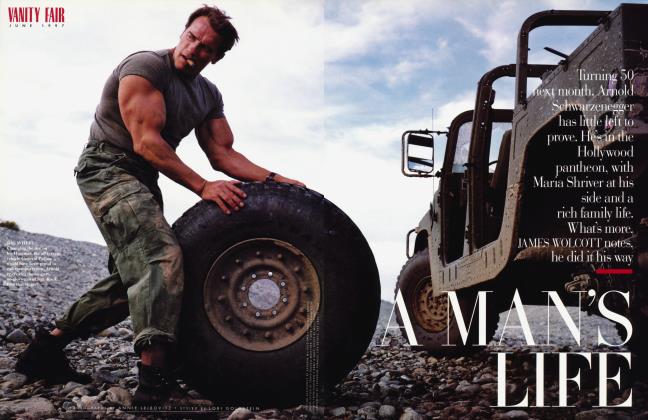

July 2004 James WolcottIt is said by passionate admirers and appalled bystanders alike that, whatever his sexual politics, President Bush is secure enough in his masculinity to be comfortable around "strong women." He says so, too. Clinging vines can go cling somewhere else, as far as he's concerned. "Why would you want to marry a weak woman?," Bush rhetorically asked in a Ladies' Home Journal interview conducted by conservatism's prose laureate, Peggy Noonan. "I was attracted to Laura because of her strength—her beauty and her strength. My mother? I didn't have any choice with her." Along with the wife he chose and the mother he didn't, the strong-willed women in Bush's satellite system include Karen Hughes, Condoleezza Rice, Cabinet members Gale Norton and Elaine Chao, and his twin-terror daughters, Jenna and Barbara.

Potent women fill a power vacuum in his psychological war room. When W. was growing up, his father was often away on oil business, leaving his mother to fume, "I would think, well, George is off on a trip doing all these exciting things and I'm sitting home with these absolutely brilliant children who say one thing a week of interest," according to Pamela Kilian's Barbara Bush: Matriarch of a Dynasty, a book I can't believe I actually read. Despite the dearth of scintillating dialogue in the household, W. and his mother had a deep bond, one that grew all the closer after his younger sister, Robin, died of cancer at the age of four. Perhaps still resenting his father's absenteeism, W. seems to go out of his way to deprecate his old man, as if agreeing with those who felt his father evinced a certain wimpitude as a political leader. In stump speeches, Bush hails Dick Cheney as "the greatest vice president the country has ever had," elevating him over George H. W. Bush, who had served as veep under Ronald Reagan. Asked by Bob Woodward in Plan of Attack if he ever solicited advice from his father regarding the invasion of Iraq, Bush bizarrely replied, "He's the wrong father to appeal to for advice. The wrong father to go to, to appeal to in terms of strength. There's a higher father that I appeal to." It must make Poppy so proud, knowing his son the president considers him too weak to dial for counsel. Between prayers, it's strong women who have Bush's ear. And damn little good it's done.

But why should we hear about body bags, and deaths, and how many, what day it's gonna happen.... So, why should I waste my beautiful mind on something like that?

—Barbara Bush on ABC's Good Morning America, March 18, 2003 (one day before the invasion of Iraq).

A tall, bullhorn-voiced woman in a size-12 shoe (capable of crushing extended ant colonies in a single stomp), Karen Hughes—a former TV reporter—has been Bush's fiercest offensive-line blocker since she began bulldozing for him in Texas in 1994. Compared with the often caustic Barbara Bush—whose put-downs are all the more armor-piercing coming from a grandmotherly figure who resembles George Washington crossing the Delaware in a floral dress—Hughes offers "unconditional admiration," writes former Bush speechwriter David Frum in The Right Man. "His wife [Laura] was his mother antidote. His aide was his mother substitute." As W.'s communications director, mother sub conducted herself as if she were Bush in drag, finishing his sentences for him, writing a book in his voice (A Charge to Keep, one of those lofty-sounding election-year droners), mouthing his words at his rote speeches, and militantly staying "on message" until she sent interlocutors around the mad bend. According to conservative columnist Tucker Carlson, she also lied on Bush's behalf. Lied without hesitation.

In 1999, Carlson profiled Bush for Talk magazine and recorded that the candidate flung the f-word around in conversation. Sacrebleu! A born-again Christian who never lets you forget it, Bush was unhappy with the disclosure, but most readers probably assumed that's how Texas he-men talk between tobacco spits. "The micro-controversy probably would have disappeared within a few days had it not been for Karen Hughes, Bush's chief press aide," Carlson recalled in his 2003 book, Politicians, Partisans, and Parasites. "Hughes began telling people, including several friends of mine, that the quotes were false. I'd made them up, she said. Invented them, probably to get publicity for myself." Untrue, wrote Carlson, and doubly untrue, since Hughes had been present during one of the interviews where Bush let fly the f-word. "He said it several times in a very loud voice."

Between prayers, it's strong women who have Bush's ear.

Carlson called Hughes to demand that she stop slandering him, only to run smack into her distortion field. Hughes insisted that she hadn't bad-mouthed him. He wrote:

Moreover, Hughes claimed not to remember a single instance of Bush using foul language, ever, at any time. "The governor does not recall using that language," Hughes said robotically, over and over. "I've never heard him talk that way."

I wish I'd tape-recorded the call. Hughes's half of the conversation would have made a fascinating case study for an abnormal-psychology textbook. The average person is incapable of lying with a straight face to someone who knows he's lying. It's too embarrassing; the charade is too obvious. There's no one to fool. Karen Hughes can do it without flinching. It doesn't seem to bother her at all. Which is either the mark of exceptional discipline or a mental condition. Maybe both.

A third alternative is that Hughes has no compunction about breaking the commandment against bearing false witness because, like her boss, she believes she's God's chosen instrument. It's His will that makes her tongue wag, and her salvation is guaranteed—she's earned a pre-boarding pass to the great beyond. On the last page of her new memoir, Ten Minutes from Normal, she foresees, "I'm on my way to heaven— not the heaven of quiet and rules that I envisioned as a child, but a heaven of joy and delight, where God has prepared a banquet, with fellowship and a big team, all in supporting roles." Hughes isn't 10 minutes from Normal, she's a few minutes shy of Nuttsville, and yet underneath her gauzy pieties works a devious intelligence well versed in the art of negative campaigning. When Bush ran for governor against Ann Richards, who had earned the wrath of the Bushies after she wisecracked that George senior was born with a silver foot in his mouth, Hughes was the one tasked to go butch against the popular incumbent and drive up her negatives. (Pitting woman against woman is a shrewd Republican ploy, protecting the party against charges of sexism. It was, recall, Barbara Bush who delivered the nastiest dig at vice-presidential candidate Geraldine Ferraro in the 1984 campaign, saying Ferraro was an epithet that "rhymes with rich.") In Bush's successful gubernatorial bid, Hughes was teamed with Karl Rove, an acolyte of the late Lee Atwater, master trickster of shit-hits-fan tactics. As Laura Flanders observed in her anthropological study Bushwomen: Tales of a Cynical Species, "The work was shared: Rove raked in opposition research, and Karen Hughes spread it to the media."

Under the guise of promoting her new memoir, she's still spreading manure as if it were the peanut butter choosy mothers choose. She expressed smarmy concern on CNN as to whether Kerry had tossed his Vietnam medals and ribbons—prompting columnist Joe Conason to suggest in Salon, "Should she open her mouth about the subject again, someone should ask her what the president did with his medals"—and slyly linked the war against terrorism with the anti-abortion battle: "I think after September 11th, the American people are valuing life more and realizing we need policies to value the dignity and worth of every life." Planned Parenthood demanded an apology from Hughes, but good luck prying anything out of her jaws.

Once, long before George W. had any designs on the White House, Barbara Bush was complaining to a friend that her daughter-in-law Columba, the wife of Florida governor Jeb Bush, was an unpredictable ditz. 'But Laura," said Bar, "now she's the one who's first lady material."

—Ann Gerhart, The Perfect Wife.

Laura Bush is a poignant figurine. There's a shadow over her heart. As a 17-year-old in Midland, Texas, she sailed past a stop sign and rammed her car into the Corvair coming through the intersection with the right-of-way. The other driver was killed. "Killing another person was a tragic, shattering error for a girl to make at seventeen," writes Ann Gerhart in her biographical study of the First Lady, The Perfect Wife. Compounding the shock and tragedy was the fact that the victim was a friend of hers—a classmate and star athlete named Mike Douglas. "The police accident report notes that the pavement was dry and the visibility excellent on the night Laura flew through the stop sign at 50 miles an hour," Gerhart writes. Laura wasn't charged in the accident, or even ticketed for running the stop sign, but she suffered for her carelessness, withdrawing into herself and taking refuge in the quiet of books. The library became her fortress of solitude, the Dewey decimal system her method of ordering the universe. In 1972 she became children's librarian at a library in Houston, later transferring to a barrio school in Austin. Her performance as a librarian was, by all accounts, exemplary.

After she met and married the future governor of Texas, giving him the Texas cred he was lacking (Gerhart: "Laura is the one with the real Texas credo, much more a product of Midland and its ethos than her husband, who was sent to prep school in Connecticut and summered on the craggy Maine coast among the old-moneyed families"), she elevated literature to the cultural agenda. As First Lady of Texas, she organized and hosted the Texas Book Festival, her dedication and courtesy winning over those unenamored of her husband. Her genuine love of and taste in literature—I took an instant shine to her when I read that one of her favorite writers was Katherine Anne Porter—suggested that a man who would marry a woman this kind and refined couldn't be all boor, could he?

Standing onstage with her husband, giving him the Adoring Gaze, she looks like a presidential doll, with painted smile, eyes agleam, and smooth cheeks carrying an extra lick of shellac. She rations her words as discreetly as did Jacqueline Kennedy (a glossier cipher), and when she does speak, her gentle voice could tuck babies into bed. "Laura Bush has one job: Laura lulls," writes Laura Flanders in Bushwomen. She lulls, she soothes, she lightly demurs. When Bush made his sheriff's boast about catching Osama bin Laden dead or alive, she teased him about his machismo and he got the message: Tone it down. On wedge issues such as abortion and capital punishment, Laura declines to distance herself from her husband in public—"If I differ from my husband, I'm not going to tell you," she once told a reporter (similarly, Barbara Bush once snapped at reporters bugging her about her son's opposition to abortion, "I agree with him on almost 99 percent of things, and shortly I'm going to agree with him on 100 if people don't stop bringing up that subject")—and yet somehow has managed to waft the impression that in private she is more moderate than her husband. Saner than the nuts around him. Bob Woodward's Plan of Attack offers a hint of verification for this sentiment. At the White House Christmas party in 2002, Bush asked Woodward if he was going to do a sequel to Bush at War, to which Woodward replied that maybe it should be called More Bush at War. "'Let's hope not,' Laura Bush said almost mournfully." One can only imagine how mournful this former librarian felt when the libraries and museums of Baghdad were ransacked while the U.S. troops did nothing and Donald Rumsfeld trivialized the looting as "untidy."

Like her boss, Hughes believes she's God's chosen instrument.

More Bush at War is a title that wouldn't have bothered Bush's other wife, Condoleezza Rice. Bush's national-security adviser recently boggled the guests at a dinner party hosted by the Washington-bureau chief of The New York Times by blurting, "As I was telling my husb—," then, catching and correcting herself, continued, "As I was telling President Bush." An understandable slip. Rice consecrates herself to Bush with bridal devotion. She believed in the war because she believes in him with her entire unthrobbing being. Woodward writes in Plan of Attack, "She is not married and has no immediate family; it seemed she was on call for the president 24 hours a day in her West Wing office, with him on trips abroad, at Camp David on weekends or at his Texas ranch.... Tending to the president and his priorities was her primary goal." Strolling together across the White House lawn, the president and his horse whisperer could easily be mistaken for a married couple, so comfortable is their body language. They move in harmony. It's as if they'd like to hold hands but mustn't, daren't. Yet I feel sure that the tending Rice does is strictly platonic. Laura is his personal wife; Condi, his professional wife. She parrots Bush's words and convictions with the faith and fervor of a nun, a sacrificial flame that burns clean. She is also the ideal daughter Bush never had, one that listens.

Raising teenagers has been a fascinating experience.... We love them a lot. And the only thing we know to do is to tell them, "We love you, so stop trying to make us not."

—George Bush, on child raising, as told to Tim Russert in 2000.

Covering the 1968 Republican convention in Miami, Norman Mailer was forced to re-examine a long-standing prejudice. Journalism is so much easier when life doesn't get in the way, but Mailer was never one to discard sensory perceptions. For years he, like so many political watchers, had pondered the lurching men ace of Richard Nixon's Frankensteinian personality, tracing the intricate, frayed coils of Nixon's duplicitous nature. "There seemed at the time no limit to Richard Nixon's iniquity," he wrote in Miami and the Siege of Chicago. But in the lobby of the Hilton Plaza, Nixon's daughters, Tricia and Julie, arrived for a rally, and in the presence of their poise, self-containment, and immaculate complexions Mailer was forced to concede, "A man who could produce daughters like that could not be all bad." Nixon's daughters revered their father, and a father who could be so revered was not without saving graces.

What do Jenna and Barbara tell us about Daddy dearest? Like the Nixon daughters, the Bush twins have been blessed with creamy complexions, but there the comparison ends. They seldom talk up their father, or show their pert noses at public occasions. It's a mental stretch to imagine Tricia or Julie getting nabbed for using a fake ID to buy alcohol, or being photographed sloppily rolling around on the floor, or, worse, making life hell for the Secret Service agents assigned to their protection. In a story in U.S. News & World Report, Secret Service agents complained about how shabbily they were treated by the First Daughters. After Jenna was refused service by a bartender in the summer of 2001, she upbraided the agents on duty for interfering with her fun, taunting one of them, "You know if anything happens to me, my dad would have your ass." Barbara, who is usually described as the quieter, more studious twin, led agents on a merry chase after she gave them the slip to attend a pro-wrestling match in New York. "Members of her security detail had to wait in the toll lane on a bridge into Manhattan, then weave through traffic at high speeds to catch up." Quite a contrast with Chelsea Clinton, who a model of comportment and consideration, according to an agent who served on her detail. "You could work with her. You could make a relationship based on mutual trust and respect. These girls don't understand that."

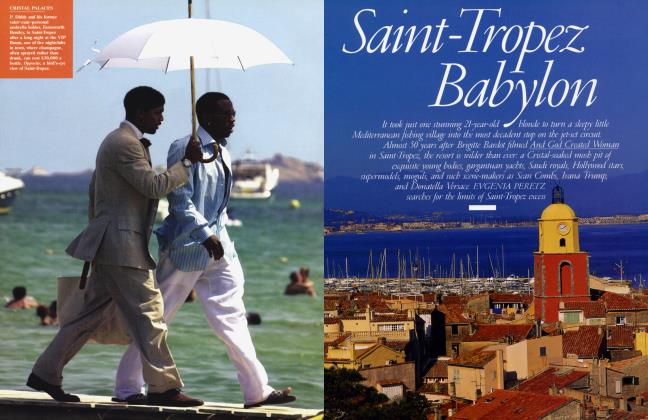

According to Gerhart, the selfish antics of the Bush twins can't be chalked up as the hormonal rebellion that hits so many young adults on their way to their first kegger. They're the product of a lifetime of coddling and entitlement almost guaranteed to spit out a pair of Hilton sisters. For supposed conservatives, George and Laura Bush treated their daughters with a permissive indulgence worthy of love-beaded, do-your-own-thing liberals. "Jenna and Barbara have not been asked to campaign. They have not been asked to rein in their adolescent rebellions. They have not been asked to appear even nominally interested in any of the pressing issues affecting this world their generation will inherit. They have not been asked to have any empathy toward the struggles and responsibilities facing their mother and their father, the president of the United States [another contrast with Chelsea, who accompanied her mother to India and Africa].... They have not been asked to show their faces at the White House very often. They have not been asked to make something of themselves in their own right." Reading about their hanging with Sean Combs and Ashton Kutcher (who blabbed to Rolling Stone that they'd been boozing at his house and partaking of the hookah), it's easy to slot the Bush twins as stuck-up babes and concur with Gerhart's verdict: "These girls have all the noblesse, and none of the oblige."

Condi Rice is the ideal daughter Bush never had, one that listens.

Why wasn't oblige inculcated in them, as it was in the Nixon daughters and Chelsea Clinton? There's something unpinpointedly awry in the relationship between Bush and the twins, a burr of resentment. Over Christmas in 2000, on the eve of W.'s joining his father and brother Jeb in Florida for a fishing trip (a bit of R&R after the protracted recount battle), Jenna suffered stomach troubles and was rushed to the hospital. She required an emergency appendectomy. Her mother slept at the hospital; her father wasn't present for the surgery and, never one to miss a vacation, didn't let it delay his exit. Gerhart picks up the rest of the story in The Perfect Wife:

The next day, he went on vacation to Florida just as he had planned. As he boarded the plane, reporters inquired about Jenna's condition. "Maybe she'll be able to join us in Florida," the president-elect said. "If not, she can clean her room." The reporters stared at him, stunned. "I couldn't believe it," one of those present later said. "First of all, I'm a father, and I cannot imagine a scenario in which my daughter would have major surgery and I would just leave on vacation. And then he just seemed so snarly about it, like he was pissed at her."

Why would a father be "pissed" at his daughter for falling ill? An emergency appendectomy isn't some little sniffle. Notice how, despite his reputed ease with strong women, Bush can't resist the domestic stereotype when the safety catch comes off his mouth. When the usually punctual Karen Hughes is late for a meeting after being stuck in traffic (she recounts in Ten Minutes from Normal), Bush, "a man who hates to wait," greets her by asking, "Did you have fun shopping?" Laura he has sweeping the porch back in Crawford like some pioneer woman. And Jenna he sentences to stay home during the family vacation and clean her room, as if she were being punished.

What no biographer has yet been able to account for is the punitive thrust of Bush that lies beneath all his Christian hokum. Whenever I ponder the rocky enigma that is Bush, I always trace back to another woman in his life, a woman he never met—Karla Faye Tucker. Convicted of a brutal double homicide, a crime all the more sensational because Tucker confessed that she enjoyed orgasms as she struck the fatal blows (like some trailer park Thérèse Raquin), Tucker spent more than a decade on death row and was sentenced to be executed. "Executions were nothing unusual in Texas; Bush would preside over 152 of them during his tenure as Governor," Christopher Andersen writes in George and Laura. "What set Tucker apart was she claimed to have undergone a spiritual awakening, to have found Christ during her thirteen years in prison." As her execution neared, Tucker was interviewed by Larry King on CNN and made an eloquent case for her own remorse and personal redemption. Her case became a cause célèbre, as such unlikely allies as fundamentalist preacher Pat Robertson, human-rights activist Bianca Jagger (who was representing Amnesty International), and a papal emissary from the Vatican, among many others, urged a stay of execution. A fairly ecumenical opposition. Even Bush's daughter Barbara expressed her opposition to the death penalty and to this particular application of it. In A Charge to Keep, Bush talks about agonizing over the decision, and he told the good people of Texas he had prayed for guidance. God apparently gave him the go-ahead, because on February 3, 1998, he condemned Karla Faye Tucker to death by lethal injection.

A year later, in the same Talk profile which found Bush swearing like Jack Nicholson on shore leave in The Last Detail, Tucker Carlson asked Bush if he had met with Jagger or any of the pro-clemency advocates. "Bush whips around and stares at me. 'No, I didn't meet with any of them,' he snaps, as though I've just asked the dumbest, most offensive question ever posed. 'I didn't meet with Larry King either when he came down for it. I watched his interview with [Tucker], though. He asked her real difficult questions, like 'What would you say to Governor Bush?'" Then Bush mimics her answer. "'Please,' Bush whimpers, his lips pursed in mock desperation, 'don't kill me.'"

Unforgivably, Bush is mocking the execution of a fellow born-again Christian that he sentenced to death. He held her fate in his fist, and squeezed. What makes his jeering even scarier is that transcripts show Tucker said no such thing to Larry King. Bush imagined her begging to be spared, fantasized a condemned woman whimpering for her life. Bush, unlike his favorite philosopher, Jesus, despises the weak. That's why he makes such a verbal fetish of "strength." He didn't meet with those wanting to spare Tucker's life because he didn't want his mind changed. The righteous never do.

Condi Rice believes in President Bush with her entire unthrobbing being.

It's time for enlightened Republican women to stop conning themselves and the rest of the populace. They have no influence whatsoever. They may express misgivings in private about abortion, capital punishment, and waging war, but Republican men such as Bush do what they intended to do all along. It's nice that they're nicer and less doctrinaire than their husbands, but that only helps promote the con job of compassionate conservatism. "The Bushwomen are the media-friendly face of an extremist administration," Flanders argues in Bushwomen, and those who keep their qualms to themselves are bequeathing a more oppressive world to their daughters. The women most useful to the president are the true believers such as Hughes, Rice, Gale Norton, Elaine Chao, Peggy Noonan, and Lynne Cheney, who mouth Bushspeak as if it were Scripture. When Bush signed the bill outlawing a type of late-term abortion, he was photographed surrounded by smiling middle-aged white male politicians who seemed to be gloating about extending control over women's reproductive rights. "Where were women from Feminists for Life or other female-led groups that sought this ban? In their place—in the audience," observed Myriam Marquez, columnist for the Orlando Sentinel. "Oh, where is Karen Hughes when [Bush] needs her?" she wailed. It's true— Hughes would have made sure to sprinkle a few bouffants into the photo-op mix. But she wouldn't have tried to change the policy, only prettied up the presentation to make it more palatable.

I've come to have a grudging regard for the Bush twins. Jenna and Barbara may be spoiled brats —tarty party girls—but at least they're not perpetuating false pretenses, being used as attractive props and tweeting pieties they don't believe. An anonymous chum was quoted in Rush and Molloy's New York Daily News gossip column as saying that the daughters "don't buy into the conservative movement," and young Barbara's opposition to the execution of Karla Faye Tucker earns her special commendation. "Every step of progress means a duty repudiated, and a scripture tom up," George Bernard Shaw wrote, and thus far the Bush twins have been undutiful daughters, licensed perhaps by their lenient mother, who's trapped in a gilded cage and cannot bring herself to sing.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now