Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

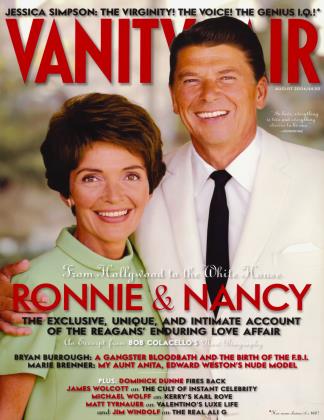

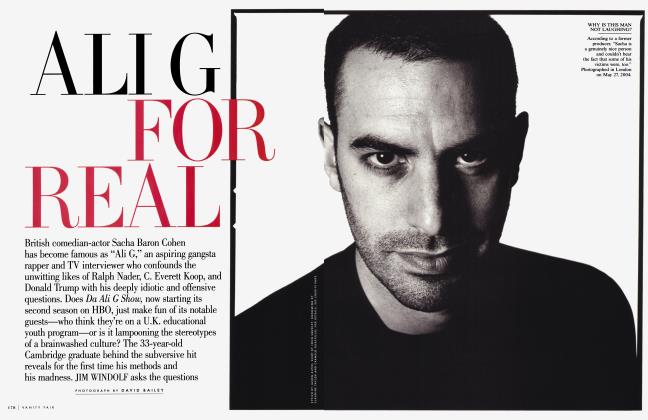

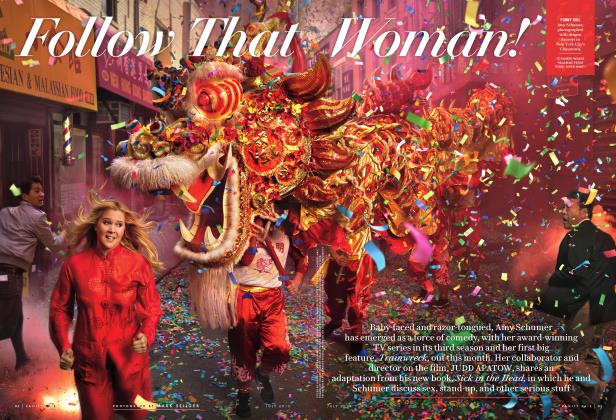

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowReturning to her roots in Mexico at 18, Anita Brenner posed for photographer Edward Weston's 1925 abstract masterpiece, Pear-Shaped Nude. So began her dazzling career as a literary bridge between Mexican culture—including the art of friends such as Weston, Tina Modotti, Diego Rivera, and Frida Kahlo—and the U.S. While new books and exhibitions mark a growing interest in Anita's Mexico City circle, MARIE BRENNER excavates the legacy of her enigmatic aunt

August 2004 Marie BrennerReturning to her roots in Mexico at 18, Anita Brenner posed for photographer Edward Weston's 1925 abstract masterpiece, Pear-Shaped Nude. So began her dazzling career as a literary bridge between Mexican culture—including the art of friends such as Weston, Tina Modotti, Diego Rivera, and Frida Kahlo—and the U.S. While new books and exhibitions mark a growing interest in Anita's Mexico City circle, MARIE BRENNER excavates the legacy of her enigmatic aunt

August 2004 Marie BrennerFor years I have imagined my aunt Anita Brenner at the tender moment when she arrived at Edward Weston's photography studio on the Calle Veracruz in Mexico City on that rainy morning of November 12, 1925. Small-boned, slightly zaftig, with dark curly hair framing her almond eyes, Anita had an exotic prettiness that was undercut by a mean, curved nose. Intellectually dazzling—at 20 she was already writing for The Nation—she was also openly flirty, and she was there that day to have her ticket punched as a free spirit and pose nude for a great man.

She was then a presence without being a reality, a girl with big plans, drawn to the power players of art. It was a time in Mexico of political and artistic ferment. Diego Rivera would soon set up scaffolding and paint revolutionary murals in the National Palace. Edward Weston, the aloof and self-absorbed Californian known in America for his portraits, was ensconced in the capital with his lover, the sultry photographer Tina Modotti. Was it Anita's hope that Weston, who was then 39, would try to seduce her or portray her as lushly erotic like Modotti? Anita surely knew that Weston slept with his models, believing they were sources of creative energy, and he made references to it in his journals. Like Weston, Anita made earnest notes about her own sexuality in her own journals, but her concern was radically different. Still a virgin, she feared that sex might cause her creative powers to disappear.

The sitting had been pre-arranged, but Weston was startled when Anita appeared, and later recorded his irritation: "I was shaving when A. came, hardly expecting her on such a gloomy, drizzling day. I made excuses, having no desire, no 'inspiration' to work. I dragged out my shaving, hinting that the light was poor, that she would shiver in the unheated room: but she took no hints, undressing while I reluctantly prepared my camera."

Did Anita sense that Weston was not elated to see her? She was a fizz of forward movement, but at times she could be opaque. There may have been an atmosphere of tension, a sense of the taboo caused by the strict censorship laws of the time. Weston probably posed her— turned away from the camera, hiding her face. Seated with her back to Weston, Anita tilted her head forward until there was little but her pale skin in the lens. Suddenly, for Weston, she lost all connection to human form. He later wrote, "And then appeared to me the most exquisite lines, forms, volumes—and I accepted, working easily, rapidly, surely." His excitement grew with each shot—15 in all. The next day, under cool reconsideration, he recorded that the pictures "retain their importance as my finest set of nudes—that is, in their approach to aesthetically stimulating form."

That night Anita was hit by a car and rushed to the hospital with a broken ankle. Weston wrote, "Poor girl! I shall send her a set of proofs to cheer her. The reckless driving of automobiles in Mexico is appalling!"

It is impossible not to speculate that Anita might have had some ambivalence about the photographs. In Weston's gaze she had been cruelly desexualized into a rounded pear, a whimsical abstract, a "trompe l'oeil of the human form," as photography historian Beth Gates Warren would say. Her nakedness was the antithesis of erotic. Did she view it purely as art? Her pale skin was mottled, and Weston detested the patterned background, which he blacked out on the negative.

The image, however, was startling, a dramatic, modernist abstraction that set the photographer on another course. It was his breakthrough, which Michael Mattis, a collector of his work, has called "Weston's first fully realized still life." It was soon printed in the influential monthly Creative Art, and Anita entered history as a masterwork of 20th-century photography, which Weston referred to in his daybooks as "nude of A."

Anita never told her daughter, Susannah Glusker, about the sitting. She mentions the Weston photograph only glancingly in her journal. She and the painter Jean Chariot, her first great love, were shopping at Wanamaker's department store in America in 1929, and he noticed an issue of Creative Art outside a dressing room. "Some sardonic fiend turned it to the abstract nalgas [rear end] Edward did of me," Anita wrote.

This summer Pear-Shaped Nude is on prominent display in a major exhibition at the Barbican Art Gallery, in London, "Tina Modotti and Edward Weston: The Mexico Years." With a total of more than 150 images, brought together for the first time, the show was organized by Modotti scholar Sarah M. Lowe. During the last decade there has been a revival of interest in the lives and work of Weston and Modotti. Most of the women who posed nude for Weston slept with him, and a number have published memoirs, including his second wife, Charis Wilson, and his first love, Margrethe Mather. Like her contemporary Frida Kahlo, Modotti has been massaged into a feminist icon. Her Roses and Mella's Typewriter are on postcard racks in stores and museums. Even as a young woman, Anita understood Tina's need for self-dramatization. "I hear that Tina is again a martyr," she wrote Weston in 1930, after his former mistress had been deported from Mexico in a messy attempted-assassination scandal. "It's a stupid business."

Anita threaded a narrative that ran from the Aztecs to Rivera's frescoes, and hoped Weston's and Modotti's photos would complement her text.

By the time Weston met Tina Modotti, she had already cut a swath through Hollywood. The niece of a famous Italian photographer, she had appeared in a 1920 film called The Tiger's Coat and was at the center of the young smart set of the movie colony. Weston, 10 years her senior, was besotted with her. Known in America for his romantic images, he was tired of being labeled just as a portrait photographer. Experimenting with modernism, he shot steel mills in the Midwest and showed the photographs to Alfred Stieglitz, who encouraged him to head south. He left his wife and three of his four sons in California and joined Tina in Mexico. Modotti was also experimenting with the camera, and she soon took to the streets to capture the passion of the worker as hero in Mexico.

Their images define the era: Modotti's campesinos, Indians sitting on petates (straw mats), mothers with plump babies on their laps, men in sombreros reading the revolutionary newspaper El Machete, calla lilies, and telephone wires; and Weston's abstract maguey cacti, laundry hanging above community washtubs, Oaxacan clay pots, and erotic renderings of Modotti and his former love Margrethe Mather.

It was a golden time; Mexico City was Paris with a Spanish accent—houses covered with bougainvillea, the pulquerías filled with young lefties, huge political murals, garish tchotchkes. The bohemian group Weston and Modotti joined called itself "the family" and included José Clemente Orozco, Diego Rivera, David Siqueiros, Miguel Covarrubias, Lupe Marin, the American journalist Carleton Beals, and later Frida Kahlo. Arriving from San Antonio, Anita Brenner quickly became a central member, counseling them on their squabbles and flattering them by writing articles about their work. As fluent in Spanish as in English, she was in Mexico to reclaim her childhood heritage and to kick over the traces of her strict Jewish bourgeois background. She fell in love with a handsome, devoutly Catholic artist, Jean Chariot. Religion would keep them from marrying, but together they planned a crazily ambitious project: to catalogue Mexican decorative arts and the role of art in the revolution. Soon Anita was promoting and employing Weston and Modotti, was celebrated by the Spanish philosopher Miguel de Unamuno, and became a confidante of Rivera, Kahlo, and the Russian director Sergey Eisenstein.

Growing up, I knew about Anita only from my father. She was a celebrity but a ghost, whose books were on our shelves but who rarely visited. My father and Anita had barely spoken since I was a child, the result of an immutable sibling rivalry and a public quarrel over a family will. Anita's absence was larger than her presence, looming on the edge of every family event. I developed an insatiable need to understand their rupture, as if collecting material on my phantom aunt could provide some clues to other mysteries.

She was born in 1905 in Aguascalientes, in central Mexico. The Brenner family fled to Texas at the end of the 1910 revolution, but Anita's formative years in Mexico would shape her life and that of my father, who was six years younger. A spa town with a thriving smelting industry, Aguascalientes was an unusual arena for a German-speaking Baltic Jewish immigrant. "Don Isidoro" Brenner, as my grandfather was then called, started as a waiter, and his bride, Paula, was a cook at the local spa. Soon the industrious Isidore was the manager of the spa, the owner of a small bank, a hardware store, and a ranch, and the sponsor of a baseball team, Brenner's Tigers. When the revolution broke out, Pancho Villa's men camped at the ranch. A family story, surely varnished, has Pancho Villa admiring my father's auburn curls. A mestiza woman named Serapia looked after the five Brenner children, and was especially close to Anita. When Halley's comet passed over the ranch, Serapia held her in her arms and said, "It means war, death, misery, hunger, and disease." Anita later wrote, "It rained ashes for a night and a day from a distant erupting volcano. The people said, 'After this, it will rain blood.'" She and her siblings knew little of the Jewish religion, but Anita would write in a short story that her people were "a race of princes."

Anita later recalled the family's attempts to escape the bloodbath of the revolution. She said that she and her brothers were taught to hit the floor when bullets were fired at their train. The family fled twice, but Don Isidoro insisted that they go back. It was believed that Europeans were in less danger than Americans, so on a final flight out of Mexico they waved a German flag. Anita was 11 when she was plunked down in the German-Jewish community in San Antonio, Texas, a world without any of the poetry of her childhood. She had watched all their possessions auctioned off in Aguascalientes, but she never shared the experience with her daughter.

When Anita was 18, she persuaded her father, who had set up a store in the former county jail, to let her go back to Mexico. It was 1923, and for the young student Mexico City was a Utopia. She wrote in a letter, "Artists, sculptors, writers, socialists, musicians, poets,—intelligentzia [sic], but not the imitation of it that we have.... That love is free is a matter so accepted that no one ever thinks to bother to state so.... Of course I bask in it.... No snobbishness, prejudice, of any sort—racial, monetary—apparent."

She filed early pieces on Jews in Mexico and described watching boats arrive in Veracruz with hundreds of immigrants from Eastern Europe who couldn't get into New York. She wrote: "The Jew ... makes his home Mexican, and he speaks Spanish, dropping his comfortable Yiddish even within the family. And in a startlingly short time he has become part of the country he has adopted." That led to a lengthy essay for The Nation about the days of Villa and the revolutionary leader Francisco Madero. Her style was florid: "We left Mexico at the end of the struggle. Our cows and horses were gone, the ranch was a mess of trenches, the crops were mud, made of black earth and the blood of veal and men." She wrote to a friend, "I feel like lifting wings, putting my typewriter under my arm and going to heaven or to some quieter place to achieve a masterpiece." Her father repeatedly ordered her home, but she ignored him. He punished her by cutting off her support. She stayed, however, and would later write, "For the dust of Mexico on a human heart corrodes, precipitates. But with the dust of Mexico upon it, that heart can find no rest in any other land." That sentiment became her mantra. She went on to become a major journalist, an anthropologist, and one of the most influential interpreters of Mexican culture of her time.

There is a possibility that our lives will be full of adventure and new scenes," Weston wrote in his daybook on April 17, 1926. "A proposition from Anita may take us to Michoacán, Jalisco, Oaxaca, and other points. I live in this hope, for I hate this city life." Throughout her entire career, Anita could attract powerful allies with the sheer force of her enthusiasms. Weston and Modotti were early conquests. Several months after Weston photographed Anita nude, he complained that he was fed up with being a salon pet, that he missed his sons and needed money. Anita came up with an idea: he and Modotti could take the photos for the survey of Mexican art and culture she was writing. She presented them with an endless list of things to shoot—icons, reliquaries, sculptures in remote villages, and milagros, the tin paintings of religious scenes that decorated shrines. She was operating largely on moxie, as Weston collector Michael Mattis has pointed out: "This act was like a kid just out of college asking Richard Avedon to shoot her thesis."

Not quite. By then Anita had burrowed into Weston and Modotti's life. She went with them to visit Orozco's studio. She reviewed a Weston show and probably amused him with her up-close view of Diego Rivera's life. One day she had walked into Rivera's studio as he was smacking his wife, Lupe Marin. Anita tried to stop him, but they both turned on her. Modotti nicknamed her Nita, but the two women had a fraught relationship. Anita kept lists of people who were "Actively Friends," "Actively Enemies," and "Actively Both." Tina fell into the last category.

By June 1926, Modotti and Weston had accepted Anita's commission. The task was herculean, he wrote, and required each negative to be made technically fine in just a few months in order to meet Anita's deadline. Weston wrote in his journal of the antiquated trains on the narrow-gauge tracks, the cargadores with birdcages and baskets of bread balanced on their heads, and his passion to acquire the earthenware known as loza. On this trip Weston and Modotti took some of their most astonishing photos, a number of which are featured in the Barbican show. In the mornings they would shoot Anita's pots and statues and milagros— 400 photographs in all. In the afternoons the couple would roam the villages. Weston took his gleaming abstract Ollas—the black pots—and the archways of Oaxaca. Weston wrote Anita frequently from the road, whining about travel conditions and her slowness in sending money. "I was damned glad to leave Acambaro ... we were stopped and searched by police—two Mex engineers were lynched there."

Traveling through Mexico, Anita observed the paganism that was at the heart of the Aztec and Mayan cultures and that served as a kind of undergirding for the country's profound Catholicism. To emphasize her thesis of cultural fusion, she homed in on art. Anita saw the Virgin of Guadalupe, now the patron saint of Mexico, as a direct link to the Aztecs' Mother Tonantzin, pointing out that the Virgin's shrine was on the site where Tonantzin had been worshipped. She wanted to introduce English readers not only to Mexico's Day of the Dead and the work of the revolutionary artist Jose Guadalupe Posada, famous for popularizing skeletons, but also to the works of contemporary artists such as Rivera, Orozco, Siqueiros, Chariot, and Francisco Goitia. In a vivid and witty style, she threaded a narrative that ran from the Aztecs to Rivera's frescoes, and she hoped that Weston's and Modotti's photos would complement her text. Weston soon became as intoxicated as Anita with Mexican culture. "Weston was in Mexico the way Gauguin was in Tahiti," Mattis told me.

In the fall of 1926, Weston delivered many of the prints to Anita and then left for California. Anita went to New York to study at Columbia University with the distinguished anthropologist Franz Boas, whose students had included Margaret Mead. Anita also helped Orozco find a patron in New York, which gave her cachet among the fashionable set at the time. She supported herself by writing for the Menorah Journal and The Nation.

Working day and night, Anita streamlined her catalogue and turned in a manuscript. Her title was sassy—Idols Behind Altars—as was her prose. She wrote triumphantly in her journal, "Payson-Clark definitely accepts the book—making it a five dollar popular opus, NOT an art book. And since they are such dam nice people and do get the point, I submit, and cut." Her timing was impeccable. The smart set in New York was getting a strong case of Mexico fever at the very moment Anita shipped a cache of works by Orozco, Chariot, and Goitia to exhibit and a 350-page book. She was 23 years old.

My quest to learn about Anita began when I, too, was 23. I became a sleuth of the lost connection. Over the following years I sought out anyone who knew her, combed through archives, and at one point made my way to Morningside Heights in New York. "I hated your aunt," Diana Trilling told me when I met her. She quickly added, "Maybe 'hate' is too strong a word.... In fact, I envied your aunt. In the 1930s she was taken very seriously at a time when I was not." I later wrote about that moment in a profile of the redoubtable author, who was the acerbic wife of the Columbia University literary critic Lionel Trilling. A czarina of New York intellectuals when their opinions still mattered in public discourse, Diana made no secret of her enmities. It was clear that Anita had found her way into the Trillings' powerful and rarefied circle around Columbia, and if at times she had been a source of irritation to Diana, she had also been a favorite of Lionel's.

Anita Brenner was the powerful sister who took center stage. She and my father shared certain traits and physically resembled each other. They were both stubborn and outer-directed; their conversations were inevitably about the present or the future, rarely about the past. For my father and Diana Trilling, Anita's emotive side was often hidden, and she disguised her vulnerability with certitude. "We all ... wear good armor," she wrote in her journals when she was 21. She would write letters to her siblings filled with bossy directives. Her own struggles were always obscured. One weekend in the Berkshires in 1929, she met David Glusker, a handsome medical student, and fell madly in love. She wrote to Weston that David was "a Galahad" who had never heard of Mexican art and was "blissfully ignorant of it yet as well as of other art, literature and anthropology." The iceman, she wrote, would soon know her as "Mrs. David Glusker," which pleased and frightened her.

On the eve of the publication of Idols, as it was called in my family, Orozco worried in a letter, "The only thing that threatens me now is Anita's book," perhaps because he feared she would favor the work of Diego Rivera over his. In May 1929, Madison Square Garden was turned into the capital of ancient Mexico for a benefit called "Aztec Gold." It was one of the most sought-after tickets of the social season, and a cast of 1,000 played roles from Cortes to Montezuma—Flo Ziegfeld was an Indian chief. Orozco, Covarrubias—who was by then a star contributor to Vanity Fair and The New Yorker—and presumably Anita had roles in the gala.

When Idols Behind Altars was published, it received dozens of mostly glowing reviews. Carleton Beals praised his young friend as "the Vasari of [the] modem Mexican school." Anita began a correspondence with Miguel de Unamuno. "Richard Hughes flatters me by saying that our styles are alike," she wrote in her journal. "I now seem to be a successful young author and strangers often know me. Which is gratifying." She was named Latin-American editor of The Nation and was awarded a Guggenheim fellowship to study Aztec art. Franz Boas pulled strings to get her excused from coursework for her B.A. and M.A. and certified her ready to pursue her Ph.D.

Her father wrote her a sharp letter: "You have taken on a load more than you can carry.... It has brought you fame [but] you are paying with sacrifice, worry ... and very likely, breakdown of your health." Soon after that Anita had a nervous collapse.

Work was Anita's protection, the reliable fact of her life. She followed her literary debut by going to Europe, where she filed her first dispatches for The New York Times Sunday Magazine. She begged the Guggenheim foundation for money for a cinematographer; it is possible she was trying to help Sergey Eisenstein, who was inspired by Idols Behind Altars for his film ¡Que Viva México! She then returned to Mexico with her new doctor husband for her Guggenheim project. To help pay the rent, Anita speedily wrote a tourist guide called Your Mexican Holiday, which stayed in print for 15 years.

As a foreign correspondent for The New York Times, she was one of the few women of the era to have a byline in a major newspaper. She railed to friends about how unfair it was that the Times would not put her on permanent staff. The scope of her reporting was remarkable. Soon she was writing about the Spanish Civil War and the turbulence in Morocco. Sent to Spain by The Nation and the Times to report on the war, she discovered corruption among the Stalinists and wrote a furious piece exposing their secret prisons and arrests. When The Nation's editor, a Stalinist sympathizer, refused to publish it without heavy editing, Anita took her story to the Times. That triumph was followed by five more pieces on Spain. By the time she returned from Europe, she was a popular figure with the New York intelligentsia. In the 1930s she would write 175 articles, nearly 50 of them for the Times. She translated three books, was on the radio and the speech circuit, and defended Diego Rivera when his murals for Rockefeller Center were destroyed.

"Petite vivacious, dark-haired Anita Brenner is more like a college girl than a full-fledged author, registered anthropologist with a PhD from Columbia," one reporter wrote in 1933. "She greets her guests in green lounging pajamas, topped with a brightly flowered coat. She bubbles with girlish enthusiasm, talking eagerly and shaking her short curls." She became famous for her parties. The Italian-born anarchist Carlo Tresca made spaghetti in her kitchen, Isamu Noguchi made a baby carrier for her firstborn, Peter, and when Frida Kahlo came to town they made a home movie, A Rose Is a Rose Is a Rose, starring the two of them, according to the muralist and photographer Lucienne Bloch. Frida wore a sign on her backside that read, I AM A F.W.—short for Fucking Wonder.

In 1938, Whittaker Chambers decided to quit the Communist Party, which he had served as an underground agent, and he started his new existence at a Halloween party at Anita's. She and David had decorated the house in the style of the Day of the Dead, with skeletons and pumpkins, and the guests treated Chambers with contempt. "Whose ghost are you?" several asked him, according to Diana Trilling's memoir. Kahlo was there that night, as were the writers James T. Farrell and Dwight Macdonald and the philosophers Sidney Hook and John Dewey. A decade later, when Chambers accused Alger Hiss of being a Communist agent, Trilling told Chambers's attorney that she thought Chambers had chosen to hide secret microfilm in a pumpkin patch because of the trauma he had endured at Anita's house that Halloween.

Republished in 1971, Idols Behind Altars is still in print. "Anyone who hopes to understand that prickly but fascinating country must read it or lay aside any claim to insight into the thoughts and feelings of Mexican people," one reviewer said. My father clipped the review, marked the date in ballpoint, and put it in his files. The wreckage between him and his sister would never be repaired, but he kept track of Anita's accomplishments and spoke of her often.

Anita died in 1974 in a car crash at age 69. Her obituary took up nearly a full column in the Times. In 1975 the Mexican newspaper Excelsior published a three-page tribute to her, saying she had "lived like the women in the novels of Graham Greene." When I read the Times obituary, I called my father. I was 24 and had just begun my own life as a reporter. The silence on the telephone was overwhelming. "My God," my father said, then hung up quickly.

In Mexico City, soon after Anita died, Susannah Glusker got a startling call. "What was the history of your mother's relationship with Trotsky?" a British academic asked. "My mother knew Trotsky?" she said, stunned. Susannah had been close to her mother, but she always understood that Anita had areas of mystery, no-fly zones. "I didn't understand why someone as famous as Henry Moore invited us to tea," Susannah told me. During Susannah's childhood, she played with Frida Kahlo, her surrogate aunt, but she ran away from Rivera—"the detestable fat man"—and refused to let him paint her portrait. After she grew up and had children of her own, Susannah used to take long drives with her mother to Aguascalientes, hoping she would open up, but she never did. One day Susannah came upon the diaries in Anita's office and asked her about them. "I don't have time to go back there," Anita told her. Soon after the call from London, Susannah went to look at her mother's meticulous files. She discovered a hidden history, neatly organized under the letter T.

In 1934, Anita had been given a plum assignment by The New York Times to try to interview Trotsky in exile. He was living outside Paris, hunted by Stalin's thugs. As the former head of the Red Army, he had been the symbol of the new Russia until Stalin drove him out. Anita described her pursuit of Trotsky: "I was told to write this Mr. X, care of Poste Restante, in a city in France. Several weeks later, a brief note arrived telling me to write to another address. ... In Paris, a voice on the telephone set a rendezvous in a cafe, asking me to identify myself in a certain way." She was told an interview would be difficult to arrange—"White Russians ... terrorists ... royalists ... Fascists ... and spies and secret agents of many sorts would have their own reasons wanting to get at him." At a third meeting with Trotsky's men, she wrote, one told her, "'Let us go.' 'Where?' 'Somewhere in France.' And I went in a closed car at night, dutifully making every effort not to look through the shutters of the car ... carefully trying not to notice how long it was taking me to get there."

Her initial impression of Trotsky was that he was a "cold, shy, harassed man," and she was put off at first by his steely gaze, "with a sharp light in [his eyes] that I have seen only twice before, once in the face of an artist and once in an explorer." She was pleased that he turned out to be "a cheerful man, with lifts of gayety." Trotsky was apocalyptic about a coming war, and foresaw that Japan would be brought to heel by an alliance of the Soviet Union and America. He reinforced Anita's views as an early anti-Stalinist, and she became his staunch defender. She was also instrumental in arranging his eventual Mexican asylum by cabling Diego Rivera. The telegram has been lost to history, but family lore says it read: "Uncle is sick and would like a Mexican holiday." Rivera prevailed on Mexican president Lázaro Cárdenas to allow Trotsky into the country, where he lived in the now famous house in the Coyoacán district of Mexico City surrounded by loyalists, tended rabbits and chickens, and had an affair with Frida Kahlo. Why did Anita never speak about it? One reason may be that Rivera, according to Hayden Herrera's biography of Kahlo, claimed that he had arranged Trotsky's asylum in order to facilitate his August 1940 assassination. It was not true, but Rivera adored being at the center of dramas. As his confidante, Anita was smeared as a Communist. Malicious gossip would float through Mexico for years. Three months earlier, Siqueiros had tried to kill Trotsky and had wounded Trotsky's grandchild instead. Anita was so enraged, Susannah remembered, that she took a Siqueiros painting off the wall and got rid of it. "Oh, my God, he's gone. What do we do now?" a sobbing Anita asked Lucienne Bloch on the morning Trotsky was killed. She was in New York and inconsolable.

My cousin Susannah and I got to know each other only as adults. Recently she told me, "I did not have a clue who my mother was." Susannah used her mother's life as the basis of a Ph.D. dissertation. It took her 13 years, and in 1998 she published a detailed and graceful biography for the University of Texas Press called Anita Brenner: A Mind of Her Own—a play on the title of a column Anita had written for Mademoiselle in 1937. This year Susannah Glusker, who is now a professor of women's studies and art history in Mexico City, will publish her mother's journals.

In 1940, Anita wrote a telling letter to Frida Kahlo, who was considering remarrying the faithless Rivera: "Don't let yourself be tied down completely; do something with your own life; for that is what cushions us when the blows and falls come.... One depends only on oneself, and from there must come everything." Diana Trilling agreed. "If you were a woman—and an intellectual—in the 1930s, it was very difficult.... You had to keep yourself at the level of celebrity or you just ceased to exist," she told me after we became friends. Diana saw Anita's problem as her own: the difficulty of being a professional woman with children to support. After David Glusker enlisted in the army and Anita moved to Mexico, far from the New York scene, the Times published fewer of her pieces—light fare about women working in the war. She had, however, managed to produce a third book, in 1943, The Wind That Swept Mexico, a pictorial history of the revolution. Still in print, it has been a best-seller for the University of Texas Press, but some critics were less than magnanimous. In the New York Herald Tribune, Katherine Anne Porter virtually accused Anita of being an apologist for the Mexican government, and called her writing facile. The era of Aztec pyramids in Madison Square Garden was clearly over. Anita's affiliations with Rivera and Trotsky made her life in America even more untenable during the McCarthy years. She became convinced, she told Lucienne Bloch, that she was a target of the House Committee on UnAmerican Activities. Indeed, when Susannah went to the National Archives to read the thousands of pages that had been accumulated on her mother, she discovered that they had been "moved to a different facility," presumably by the F.B.I.

The pressure on Anita in the 1950s was intense: her marriage disintegrated, her beloved father, Isidore, died, and family members went to war with one another. Marooned in Mexico, Anita re-invented herself once again by calling in favors and launching Mexico/This Month, a magazine with frequent illustrations by Chariot, Rivera, and a new generation of Mexican artists. It lasted 17 years. Susannah recalls a colleague describing her mother during that period: "She was on three phones at once, and there was always a crisis—the writers were not getting paid, the art director was threatening to commit suicide." Anita had inherited the family ranch in Aguascalientes and was trying to raise asparagus commercially. "If she couldn't pay the writers, she would send them crates of asparagus," Susannah said.

The writer Budd Schulberg lived in an apartment behind Anita's office. "She would walk the balcony, pacing back and forth. Then at night I would go to her parties. Everyone who was in Mexico City came." Her house was filled with ambassadors, movie stars, artists, and Israeli agriculture experts, but Anita remained a paradox, an introvert with an extrovert's disguise. Some compared her to Gertrude Stein, others to the author and editor Fleur Cowles, and everyone visiting Mexico angled to get an invitation to her house in the elegant suburb of Lomas. "It was always the here and now, and politics," Susannah recalled. She tried to understand her mother's contradictions; Anita, who had always been superstitious and spiritual, became obsessed with the I Ching. In her last years she was convinced that there was gold buried on the ranch. She had her son, Peter, come from the U.S. with a metal detector, but all they ever found were bottle caps and old license plates. In 1972 she was awarded the Aztec Eagle, the Mexican government's highest honor to a foreigner. (Anita refused it on the grounds that she was Mexican by birth.) It took Susannah years under the Freedom of Information Act to get the files on her mother, and when they became available, large sections were blacked out. One of Anita's last projects was a study of the life of Moses for young people.

Next year Mexico City will celebrate the centennial of Anita Brenner's birth. Susannah is arranging an exhibition of her mother's extensive collections, including hundreds of Weston and Modotti photos. No vintage print—one made at the time of the negative or soon thereafter—of Pear-Shaped Nude has ever come up for auction. In 1975, the writer Janet Malcolm requested the photograph to illustrate a Weston review she had written for The New York Times. The editors refused, believing it to be, in Malcolm's words, "too racy." In 1992, Sotheby's auctioned a 1930s version. I was in the room then and believed that my aunt's abstract "nalgas" had sold for nearly $80,000. I recently learned that on that day at Sotheby's, in fact, the photograph had not met its reserve. Experts say a vintage print would command as much as $500,000. Last November collector Michael Mattis cited Pear-Shaped Nude in an article in Art News about the most wanted works of art. It took him years to discover a vintage print and even longer to negotiate with one of Anita's heirs. "What did you know at first about the woman who sat for the portrait?," I asked Mattis. "Very little," he said. "She was a complete mystery. I thought of her for years as 'Nude of A.'"

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now