Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

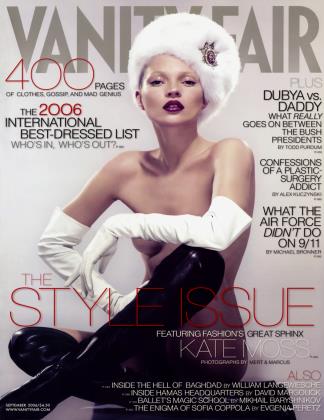

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowWhen a movie star joins the faithful's Milan pilgrimage to report on the men's collections for spring and summer of 2007, the clothes are only half the story. Rushing from Dolce & Gabbana's triumph of the will to Donatella's soccer-mania at Versace, to the sleek crescendo of Armani (and Clooney), RUPERT EVERETT discovers that the mantra is "Bermudas," and the bitching gets worse as the week goes on

September 2006 Rupert Everett Michael RobertsWhen a movie star joins the faithful's Milan pilgrimage to report on the men's collections for spring and summer of 2007, the clothes are only half the story. Rushing from Dolce & Gabbana's triumph of the will to Donatella's soccer-mania at Versace, to the sleek crescendo of Armani (and Clooney), RUPERT EVERETT discovers that the mantra is "Bermudas," and the bitching gets worse as the week goes on

September 2006 Rupert Everett Michael RobertsIt is Men's Fashion Week in Milan and there's a heat wave. Breathless and bleary in the polluted haze, "believers" from across the globe wait in lines outside the palazzi of their household gods. It's showtime again. It reminds me of a schoolboy trip to Lourdes, a traffic jam of bath chairs stretching into the distance toward the grotto, the faces of the sick, the priests, the scribes, the gurus, and the converts bathed in the lunacy of faith, waiting for communion with the Divine. Maybe this season we will throw away our crutches and be reborn next summer with a new silhouette offered to mankind at the high altar of one of our favorite saints.

In the week preceding the shows our saints are sewing in their palaces—or at least their teams are. Trucks arrive (late) from the country with the clothes. Castings and fittings stretch into the night. The designer must communicate the dream to Korean cable networks and South American department stores. Will it be "80s" or "Oscar Wilde" or just prim again like last season? And does it really matter, because, as everyone knows, no one is going to wear many of the clothes anyway. The fashion show is the monstrance for a host of handbags, hand creams, and home furnishings; after all, the designer himself would never dream of wearing anything but a black T-shirt and trousers.

For the time being the streets are quiet, punctuated by cheers from bars where the World Cup plays. The odd TV crew scuttles through the shadows. Manolo Blahnik takes the air before dinner with his business manager, George Malkemus, along Via Montenapoleone. He is the queen mother of shoes, but together they are Bette Davis and Maggie Smith in Death on the Nile, scrapping their way through potato croquettes at the bar of the Four Seasons Hotel before supper in the dining room, swatting at unseen mosquitoes and talking very fast about the old ladies at the next table. ("This is chic—really—I mean it. Sorelle Fontana. Before your time!")

High in the sky, the birds of prey begin to circle: the critics, the stylists, the models, the fairies and the freaks, and, of course, flapping around in borrowed wings—me. I am the embedded celebrity, attending every show swathed in the robes of each household god. I will live and breathe the dream. The celebrity is an essential cog in the machine of fashion, the word made flesh. Movie stars bound down the red carpet in Armani. Supermodels go to court with Prada bags. Hip-hop guys in designer bling gun one another down, and the world says, "I want to be like that!" The stars milk the designers till their teats are sore; some have been known to clean out entire stores in one swoop from Parnassus. This is not the courtly liaison of Hepburn and Givenchy, or Armani and Gere. It is a full-on offscreen feeding frenzy of ambition.

The shows begin on Sunday morning. The streets are empty. Church bells clang and Manolo's smart old ladies walk to Mass as we race through the city toward the first show of the season—Jil Sander. The house of Sander has been through the wars. Jil, a German minimalist, sold her name and company to the Prada Group in 1999 and, as other designers have learned to their cost, selling one's name has much vaster implications than one ever imagines on that heady day one signs one's life away. The soul is somehow bought as well, and Jil's marriage to Bertelli was in dire need of couples therapy. Soon she left her own house forever.

Now Raf Simons, a talented designer from Antwerp, has taken over. He must build his nest on the foundations of the house.

So who is the Jil Sander man? Do I want to be him, and what can he do for me? Is he a lesbian? The little black suit I'm wearing from the store is heavy and tailored. The short jacket feels like a corset, but the effect is clean and simple and I feel like a Swedish journalist. The clothes on the catwalk are minimalist, boxlike, and boyish—narrow trousers and big shoes, beautifully made in black and beige, with bright-colored Pakamacs and jerseys, but there is no mystique in the narrow leg of the trouser. At least not for a man. The very minimalism seems to reduce masculinity to limp adolescence, and, almost as if to make this point, the models file down the catwalk listless and shell-shocked, a Zoloft generation of schoolboys on the way home from an act of violence.

Dolce & Gabbana have their own space for shows—a huge vaulted tunnel in stainless steel with a runway down the middle. Black curtains swish open to reveal an imposing white set—steps and columns that might have been designed by Mussolini for his model city of EUR. The Vangelis score from Chariots of Fire blares from the sound system, and shiny, muscular men stand in a frozen tableau that is sheer Leni Riefenstahl. Boys in satin Bermuda shorts and tops, white cargo pants, and beautifully cut silver-gray jackets storm through the Wagnerian wall of sound. The message is not lost: "Dolceland über alles"

Sometimes themes crop up. Different gods have the same idea on the same day, and suddenly a movement begins. By the end of the first day there is one word on everyone's lips: "Bermudas." This year, it is tailored suits with knee-length trousers. Get ready, men! From Missoni to Bottega Veneta, from Dolce to Prada, the saints are telling us to wear an outfit that if you stand with your legs together you look like a lady in a skirt and jacket. Is man becoming woman? And is fashion to blame? Smoldering movie hunks discuss their clothes on the red carpet like proud housewives. Football stars clamber all over each other at the first opportunity. Apparently this is nothing more macabre than manly high spirits. But I don't expect many Vikings wrapped their legs around each other after a looting session.

Suzy Menkes is a fashion legend—the critic for the International Herald Tribune. Hers is the immediate response to the catwalk madness, appearing the day after a designer's show. The gospel according to Suzy is the opinion upon which the rest of us build our faith. She beetles through the pre-show throng like a chorus member from The Mikado who is late for her entrance, although in Suzy's case it's her exit. She is never late. She has a roll of hair on top of her head, liberally sprayed, the work of one gauge-four roller; a penchant for baggy embroidered robes; and a large designer bag from which all manner of paraphernalia appear. She is old-school—thorough, funny, and moody—and she doesn't necessarily take kindly to tourists on her turf. I adore her.

"Why aren't you writing anything down?" she snips as we sit in the sweltering heat of the Alexander McQueen show. Mahler's Fifth Symphony plays and huge muslin curtains billow in the breeze. "Surely you can't remember it all?"

"Well, normally, there's only one thing to remember, isn't there?" I reply nervously.

Suzy snorts slightly and continues scribbling. Some boys in baggy suits with big hats and veils walk past.

"I'm hardly going to forget a boy dressed as Silvana Manyana from Death in Venice mincing by, am I?" I ask. "Not Manyana, fool! Mangano!"

"Whatever," I continue, undeterred, as a fleet of boys in high baggy trousers and poorboy sweaters cruise by. "Anyway, le feeling is more Helmut Berger in The Garden of the Finzi-Continis, non?" Suzy looks at me witheringly.

"Are you talking about yourself or the show?" she asks sternly, and turns her back. I fight an urge to tickle her under the armpits. Instead I take out my smart crocodile-skin Prada notebook and look busy.

So, is the McQueen man trapped in a city riddled with plague, or playing one last game of tennis before deportation? Either way, McQueen himself seems bored by his own fin de siecle romance, brilliant as it may be. As the show ends, I suggest this to Suzy.

"It's all a bit mañana, isn't it?"

"Silvana Mañana! That's good. Lost without anger," she replies, and burrows off to the next show.

We are already frazzled by the time the Prada show begins that evening, in some raw space on the outskirts of the city. Now I am glossy in a classic black Prada suit, a blue-and-white shirt, and a patent-leather watchband wrapped around one cuff (my own personal homage to the style of the late Gianni Agnelli). I wave my crocodile-skin notebook at Suzy across the runway. I am feeling great—light, executive, sexy—and settle down with my pencil, ready to enjoy one of my favorite designers. Unfortunately, my delirium is short-lived. We might as well be watching a student show at St. Martins College of Art, in London. Bony-legged lads in shorts with woolly socks and sandals (a look hitherto reserved for German tourists) parade past the speechless, exhausted faithful. There is a feeling of panic in the air. This is Miuccia at her most contrary. How are we going to spin this one? Patent-leather "outback hats" missing only corks hanging from their brims sit upon messy hair over crumpled metallic mackintoshes tied at the waist. I look at my suit, at the many suits I have loved over the years, and back at the show. There is no relation.

"She always does this straight after a commercial collection!" says a flustered high priest, off the record. "She wants us to ask questions."

"Where's the door?" is the only one I can think of as I watch Suzy accelerate from 0 to 60 in 10 seconds, from her seat toward the exit. I make my way backstage to shake hands with Miuccia, who, like a Greek goddess, has come down to earth tonight disguised as an Italian seamstress in sensible court shoes.

The Versace show has been specially edited to fit into the halftime of the match between Italy and Australia in the second round of the World Cup. In Donatella Versace's dressing room there is a wide-screen TV where a makeup mirror used to be, and she and her entourage are glued to the game.

This is curious, I think to myself. The Medusa herself is wrapped in an Italian flag, and when Italy scores she runs through the backstage area like a crazy bird. This girl never ceases to amaze. In the old days there was never any mention of soccer, but by the looks of things, soon she will probably be captain of a girls' team. And she's only on step three! In this hysterical atmosphere the first show begins. I stand in my favorite place, behind D.V., watching as she checks the models before they go onstage.

The next shock is the collection. It is completely new, a total departure. Gone is the aggressive rock 'n' roll bling. The new silhouette is soft, thoughtful, and romantic, with sloping shoulders and baggy jackets. A student revolution in pastels. Black is the black hole of the past. The Versace man is almost Chekhovian. He's come a long way from the Euro hustler in tight white pants and Cuban heels. So has Donatella. She pokes her head onstage for her bow before rushing back to her room for the second half of the match. Meanwhile, the faithful are taking their seats for the next show. They must wait until Italy wins. Viva la diva. The hippest name in men's fashion this week is Dsquared2. Dan and Dean are identical twins until you get to know them. On deeper inspection they are both quite unique monsters. They began as cross-dressing nightclub promoters, and in 10 years have built up a fashion business that brought in nearly $70 million last year. It's a classic drags-to-riches story and should be made into a film. They are the gay gremlins of Milan.

There is always a strain of Montagues and Capulets in fashion. Saint Laurent and Lagerfeld. Puma and Adidas. Armani and Gianni Versace. (D.V. is not warlike.) Now it's Dolce & Gabbana and the naughty twins. But while D & G micro-manage everything to the last detail, right down to their catwalk appearance, the twins live in another dimension, and that is their strength. They brought the club scene with them into fashion, but they are not prisoners in their temples. They actually go out to dinner like normal people, although sometimes the effect can be quite chaotic. While at lunch one day with Dean, the lovely lady from the restaurant (Tagiura) is chatting about our meal. "It's just like your mama would make at home," she says. "Honey!" replies D. "My mother peeled potatoes in prison. When she wasn't in solitary!"

What I love about them and Neil Barrett, who dressed the Italians for the World Cup and is the other "young" designer (they are close friends), is that they are what they do. The twins are effortlessly creative. Maybe they have less technique than D & G or Neil. They learned how to cut and stitch in nightclubs, and they don't seem to know much about the past in fashion. This results in a freshness and affection in their outlook. It will be interesting to see if they turn corporate. Most people do, because the only way is up in this rat race. A comfortable business equals dead meat these days. Expand or die! But at 9:30 in the morning it's too early for turning, and they present a fresh, humorous, sex-obsessed show of clothes they wear themselves, or, if they don't, they are shagging someone who does. After Donatella, Dean is my favorite person in fashion.

THE BIRDS OF PREY BEGIN TO CIRCLE: THE CRITICS, THE STYLISTS, THE MODELS... AND, OF COURSE, ME.

Neil Barrett's show is the one I like best. The Barrett man is a corporate skinhead in tie-dyed drainpipes and white-laced construction boots, with short pin-striped jackets over fitted white shirts. The boys on the catwalk are easygoing and fashionable, and while the faithful kneel in front of their icons chanting "Ber-mu-da" late into the night, Neil already did it last season.

On the last evening of the week, limping into his compound like the final ships of an armada, the faithful have become bitchy and uncharitable. I have been accused of "stirring" by the editor of U.S. GQ. Up to a point he is right. But if you're a water sign there's nothing else to do if you don't want to stagnate. He sent me flowers and I didn't thank him. Well, I couldn't find him. Sorry, Jim. VERSACE Thanks for the flowers.

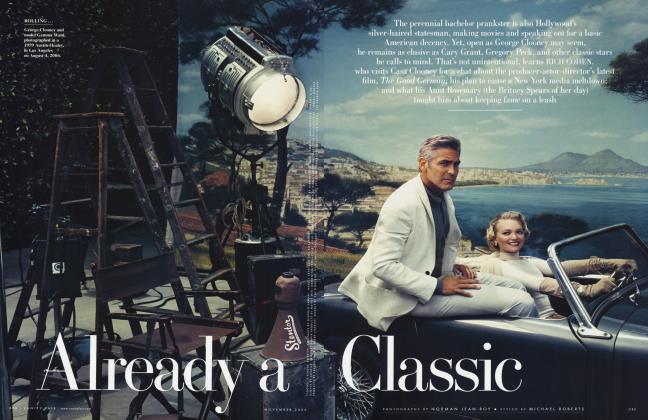

I have to get away. It's all too much, this endless obsession with fashion. Bombs are exploding all over the planet like fireworks, but no one here is remotely interested, because George Clooney is arriving. He is rushed through the crowd, flanked by Armani guards. They all have gray suits and short, gunmetal hair. He is the bride and they are the bridesmaids. Here we are, finally at the high altar to witness yet another arranged marriage between fashion and Hollywood. It is a ballet in flashbulbs: exclusive, sexy, though at the end of the day deeply divisive.

But this is probably deeper than any of us wish to probe. So, for the time being the Armani theater is huge and cool, with comfortable seats, and the great thing about Armani is that what you see is what you get, which is quite a feat in a week of shows where the designers seem to be put out almost, convinced that their amazing pent-up creativity is somehow thwarted by the mundanity of having to make a trouser with two legs. Giorgio's clothes look like Armani—sleek, wearable, and tasteful. There is a total unity between the catwalk, the campaign, and the store. And that may be why he is still the most successful designer in European fashion.

The shows end as suddenly as they began, and Milan is reclaimed by its haughty, patrician inhabitants. The faithful clatter off to the airport. Thunder rumbles in the sky, and after a last lunch in a deserted Bice, I am caught in a deluge of rain. The streets steam and shine, and this season's footprints are washed away. The bar at the Four Seasons is like a holiday resort off-season. No more Manolo at his usual table. Gone are all the collagen disasters that look as if they were permanently pressed against a plate of glass. In sports jacket, my room I pack all my beautiful new clothes. The Gucci suit that makes me feel like Cary Grant and not like the mad, matchstick freak in white drainpipes and pixie boots that stormed onto the catwalk at the beginning of their show. The Burberry blazer that turns me into Terry-Thomas with a twist. The Valentino bomber jacket with the white toweling interior. I love them all with a special new intensity. Now that I am Press, they are probably the adored children of 12 broken marriages. What was once color has turned to the black and white of words on a page.

For the most part the household gods come down to earth to frolic for the press. They are happy if we love their jokes. But if we don't, all hell breaks loose. And so we trundle on, lost in repetition, scratching another's backs until they're raw, waiting for the odd moment when our faith is rewarded with a miraculous fact. For the time being that "fact" is Bermudas. I agree with Valentino, who, the other night at dinner, said the one true thing of the trip: "The designers have got to stop joking!"

I am back in London, on the road to the hospital where fashion icon Isabella Blow is currently recovering from two broken ankles. I need some advice. She has been an inspiration to some of the most influential names in fashion—McQueen and Treacy, among others. We have been friends since we were 15. I lie on her bed and tell her about the shows. Isabella sits in the chair wearing a black beaded McQueen dress from his graduation show at St. Martins. A stuffed swallow with a broken rosary in its beak sits in a nest of tulle on her head, looking down at her famous puce lips. We smoke cigarettes and eat whitebait. We are both exhausted: me by Fashion Week, her by life.

"Why do the collections make you feel so empty? What is it?" I ask Issy.

"Money," she replies simply. "It's McDonald's these days. You go in. You get photographed. You think you're watching beautiful people in wonderful clothes, but actually you're in a sausage grinder. You forget who you are. You might have a luxury brand name written over your tits, but is that enough? In the end I was just a hat with lips, and that's not chic."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now