Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

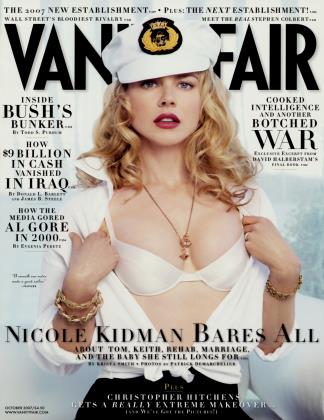

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowAmerican Beagle

THE FUNNY PAGES

The huge success of “Peanuts” threatened to turn Charles Schulz’s cutting-edge comic strip into a cuddly brand. But then Schulz remade Snoopy into a rebellious beagle who was the spirit of 60s America

David Michaelis

In November 1999, Charles Schulz suffered a stroke that forced him, in his 50th year of drawing “Peanuts,” to put down his pen. Hospitalized, the 77-year-old master was discovered to have been stricken also with the later stages of colon cancer; and on February 12, 2000, hours before the final “Peanuts” strip appeared in Sunday newspapers around the world, Schulz died at home in Santa Rosa, California. To the very end, his life had been inseparable from his art.

Excerpted from Schulz and Peanuts: A Biography, by David Michaelis, to be published this month by HarperCollins Inc.; © 2007 by the author.

To die as his last strip was going to press seemed to many a poignantly miraculous end, and all through the early hours of February 13, newspapers bearing both his farewell to “Peanuts” and the world’s first good-byes to him thumped onto porches and doormats, dismaying and saddening millions. He had finished the 50-year run of “Peanuts” with the bereft valedictory “Charlie Brown, Snoopy, Linus, Lucy ... how can I ever forget them ...” But it was he who died, not they; yet now they shared, as columnist Ellen Goodman pointed out, the “same national curtain call.”

Wistful appreciations crowded the front pages of next day’s—Valentine’s Day’s— morning editions: YOU WERE A GOOD MAN, CHARLES SCHULZ!, cried the San Francisco Chronicle, SIGH, went the Los Angeles Times. “At strip’s end, he’s gone to meet the Great Pumpkin,” reported The Dallas Morning News, AAUGH!, wailed the Baltimore Sun, NO MORE “PEANUTS.” “Good grief, indeed,” began the Minneapolis Star Tribune’s obituary.

Tributes began to spill in from around the world, for like the beloved characters of Charles Dickens, the “Peanuts” gang had transcended local papers to become universal figures whose adventures were followed by some 355 million readers in 75 countries and 21 languages.

THE PENCIL THAT MADE A GOOD PART OF HUMANITY SMILE DAILY HAS BROKEN, lamented the Vatican’s L’Osservatore Romano, illustrating its farewell paean with the first cartoons ever to appear in that newspaper.

From Rome to Paris to London, from New York to San Francisco, from Tokyo to Jerusalem, the world hailed Charles Schulz as a presence like no other—a “gentle genius” and, despite his own protestations to the contrary, a “very great artist indeed.” The New York Times, which had never given space to comics, treated his death as headline news and, as if catching up for lost time, devoted the better part of two full pages to “Peanuts” highlights and detailed profiles of the characters.

“Peanuts” had been so many things to so many people (an “ongoing parable of contemporary American existence”; a “distillation of modern childhood”; a “comic opera”; a “personal work” and at the same time a “universal language”), and there were so many commercial markets in which to quantify its success—as a daily and Sunday comic featured in a world-record number of newspapers; as the longest-running cartoon special on television, which of itself had fathered a year-round series of sequels marking the holidays on the national calendar; as the most-produced musical in the history of the American theater, with more than 40,000 productions of You’re a Good Man, Charlie Brown—some 240,000 performers had played Schulz’s characters and the show had spawned a generation of actors; as a jazz album of show-business standards; as best-selling books, both original and reprinting the strip; as advertising for cameras, cars, cupcakes, and life insurance in an ever-expanding universe of media, including hot-air blimps; and, not least, as an internationally renowned brand of character merchandise, with more than 20,000 officially licensed products and countless pirated knockoffs—there seemed no end to ways of commemorating its creator.

The reader took Snoopy s rooftop meditations for his own.

Millions of fans felt as if they had lost a personal friend. Sometimes their affection and awe had been inspired by a short handwritten response to a fan letter, a brief encounter at a golf tournament, a single meeting in a restaurant; sometimes it was simply a gesture, or the time Schulz had taken to listen, or the check he’d written to meet someone’s need—all to people unknown, whom he had touched deeply, so often at some critical moment. His decency, his generosity, changed their lives forever; and they swamped his studio mailroom with formal condolences, which crested over into his household, vibrating to the single refrain: I loved Charles Schulz.

Perhaps the main reason we loved Schulz, though, was that he charted his life and feelings in the strip. He gave his determination to Charlie Brown, the “worst side of himself” to Violet, to Linus his dignity and “weird little thoughts,” his perfectionism and devotion to his art to Schroeder. He even diagrammed some of his most important relationships, endowing the dynamics between Charlie Brown and Lucy and between Lucy and Schroeder with the emotional realities of his first marriage, to Joyce Halverson Schulz, which ended in divorce in 1972.

The writer Laurie Colwin once asked Schulz: “If you followed [the strip] from the beginning, could you actually write a biographical portrait of [you]?” He answered, “I think so.... You’d have to be pretty bright, I suppose.” He seemed, almost, to be testing us to find him in his characters. “They are all essentially me,” he said, as a gloss, but when pressed, he would admit: “The sarcastic part of me is Lucy_The wishy-washy part of me is Charlie Brown. Snoopy would be the dream to be, I suppose, the superhero.”

Despite Schulz’s efforts to keep it for adults, “Peanuts” had become by 1966 and would ever after remainin the public’s mind—family entertainment passed on from parent to child. The Charlie Brown TV specials—more than 75 in the end, 16 of them with music by Vincent Guaraldi—had recast “Peanuts” as a holiday tradition for children while refashioning the national calendar for adults, drawing attention to the highly marketable role of the “Peanuts” gang as stand-ins for Americans at all their year-round rituals: consuming too much on New Year’s Eve, exchanging valentines, planting trees on Arbor Day, hunting Easter eggs, celebrating the Fourth of July.

Older newspaper readers still engaged the seasons and their passage accompanied by the slow, regular beat of the daily and Sunday “Peanuts” and its intramural traditions—Woodstock’s New Year’s Eve party; Snoopy’s bales of valentines; the Easter Beagle; Peppermint Patty and Marcie at summer camp; Lucy setting up the football; Linus in reverent vigil for the Great Pumpkin; Charlie Brown finding himself as he finds purpose and meaning for the sad little Christmas tree. But, more and more, “Peanuts” was evolving into a world of video and plush.

Critics noted the change from a “Peanuts” that was primarily a commentary for adults to one that was a brand for children.

“After all those years of ‘Have you seen “Peanuts” this morning?’ and clipping out those capsule expressions of guilt and inadequacy to pin to office bulletin boards or magnetize to family refrigerators, it was hard to trail off. We kept trying to be amused,” wrote Judith Martin, also known as Miss Manners, in The Washington Post in 1972. “But the little bursts of identification became less and less frequent. Partly it was the repetition of ideas. Once you knew the “Peanuts” calendar—Beethoven’s birthday, baseball season, summer camp, opening of school, Great Pumpkin night, football season—it began to get tedious.”

“Should one blame him for milking all the commercial advantage he can out of the system which, it should be remembered, he had to embrace before he could claim our attention? Really, it is too stupid,” concluded the critic Richard Schickel. “That we of the middlebrow audience are no longer compelled to clip his cartoons and pin them up on the office bulletin board, quote them at parties, and discuss their hidden depths with fellow cultists is not, finally, his fault. He did not go into the cartooning business just to please ‘we happy few.’ He would, indeed, have failed if we were his only audience. No, he went into it needing, for economic success, all the friends he could get.”

“I hate to think about it,” Charlie Brown says when faced in 1966 with Snoopy’s real needs as a dog. “The responsibility scares me to death.”

The unprecedented success of “Peanuts” as a brand (with gross earnings of $20 million by 1967, $50 million by 1969, and $150 million by 1971) initiated an inner schism that would endure to the end of Schulz’s life. “I’m torn,” he would say, “between being the best artistically and being the Number One strip commercially.”

Strip and brand pulled Schulz in different directions, dividing him between the roles of cartoonist and entrepreneur, making him feel strong, indeed omnipotent, at one creative moment, dependent and vulnerable at the next executive juncture. But in 1967, as “Peanuts’” broad-based audience began gradually to come to terms with the nation’s unease about civil rights, the war in Vietnam, sexual freedom, and so much else, Schulz regained control by turning to the one character in his strip who could single-handedly re-establish the personal quality of his making.

Snoopy had come a long way from the puppy who, despite being “very smart”—indeed, “almost human,” as he was seen in “Peanuts” in 1951—had entered the strip as an ordinary domestic pooch, not even yet a beagle. By the early 60s, as the “Peanuts” marketing pioneer Connie Boucher was rendering Snoopy the cuddliest dog on the planet, his tougher image served, with Schulz’s permission, as war eagle for the United States military: in Vietnam as a talisman on American fighter planes and on the short-range Sidewinder air-to-air “dogfight” missile, in California as an insignia emblazoned on aircraft spearheading the flight-test program of the GAM77 Hound Dog strategic missile, and in Germany as a flight shield for the “Able Aces” of the air force’s 6911th Radio Group Mobile, patrolling the skies over Darmstadt.

Typical of Snoopy’s many-sided appeal, he also served in deliberate violation of army regulations governing the helmets of assault-helicopter pilots alongside such emblems of anti-war sentiment as rainbows and slogans such as “Bum Trip.” More than Rin Tin Tin, Lassie, Trigger, and even Old Yeller, Snoopy had taken his place as the American fighting man’s most trusted friend when going into combat.

Of all Schulz’s characters, he was the slowest to develop. Not until January 26, 1955, had he finally come out with his essential dilemma, announcing to himself that he was tired of depending on people for everything and wished he were a wolf. Then, like a frustrated child breaking a long, moody silence, he declared, “If I were a wolf, and I saw something I wanted, I could just take it.” To make his point, he growled a humansounding AARGH!! through a set of distinctly lupine fangs, whereupon the earnest, smiling, -everyday presence of Charlie Brown immediately dislodged him from this wild new height of power, and he ended the episode hanging his head, his face crosshatched with embarrassment.

"I'm not a philosopher,” Schulz insisted, sometimes adding, Tm not that well educated.”

“There’s nothing more stupid than someone trying to be something they aren’t,” Charlie Brown repeatedly reminded his alltoo-human dog, only to be foiled repeatedly by Snoopy’s bravura talent—a gift for silent comedy so great as to turn instruction for a simple party trick into a Chaplin-esque commentary on the human condition.

Ever the subversive comedian, Snoopy could not resist uncanny impersonations of Violet, Lucy, Beethoven, a baby, even a certain mouse.

Schulz’s satiric take on the supreme cartooning figure of his youth (drawn two months after a chuckling, affable “Uncle Walt” had welcomed some 90 million viewers—more than half the nation’s citizens—to the televised debut of Disneyland) shows one of many strengths that one day would enable Snoopy to challenge his Disney rival for universal stardom: Mickey’s ears were as rigid as sharks’ fins, whereas Snoopy’s yielded to a wide range of expression, reshaping themselves in response to cold and heat, insults and rewards, food and music, joy and sadness, fear and shock, surprise and shame, pride and disgust.

Mickey Mouse had no capacity for states of mind. As a supremely representative figure of the American world of action—pluck personified, modest but mischievous, a dancing World War I doughboy maturing into the age of Lindbergh—Mickey had become a Douglas Fairbanks-size movie star from the moment he uttered his first words, in 1929: “Hot dogs!” As bust followed boom, Disney extended his action star into situations that proved time and again throughout the Depression that Mickey was indestructible.

But the more Disney became an entrepreneur of technique and spectacle, the more his cartoonists and animators called on Mickey to do little beyond playing straight man to newer comedic pacemakers such as Donald Duck and Goofy. Then, in 1955, with the simultaneous rise of The Mickey Mouse Club on television and the opening of Disneyland, Mickey once again became the franchise star, his very ears the icon of worldwide commerce, while he himself revealed so little individual personality—his mind such an affable blank—that the viewer could not know what was going on between those ears. To be sure, from the beginning he had had energy and an unconquerable heart, but never did he have an inner life. Schulz repeatedly pointed out that nothing that Mickey Mouse had ever said, much less thought—no word or phrase—had passed lastingly into national consciousness.

In “Peanuts,” energy made Snoopy lovable but thought made him human. Schulz perceived that, although we cannot possibly know what a dog is thinking, the impulse of all dog owners is to imagine that we alone know what our dog is thinking, and the proudest of dog owners will often explicate with great subtlety what their sidekicks are now “saying.”

Snoopy’s stardom grew out of Schulz’s ability to create an intimate bond by letting the reader in on the dog’s continual awakening to his most human thoughts. The basis for this bond was trust: the reader could count on Snoopy to be himself, even when he was being someone else. The cartoonist, meanwhile, could be depended on to turn to comedy Snoopy’s dominant traits—an almost arrogant commitment to independence (and its flip side: a deepseated fear of dependence), a grand, dreaming self continually deflated—not by mediocre vaudeville gags pulled out of the filing cabinet by a studio bureaucracy, but by the more exacting and individualistic physical comedy of the silent-movie clowns of Schulz’s boyhood Saturdays at the Park Theater in St. Paul.

Snoopy extended body and mind into identities that conveyed the restless spirit behind them: rhinoceros, pelican, moose, alligator, kangaroo, gorilla, lion, polar bear, sea monster, vulture, all of which would eventually give way to the serial “WorldFamous” archetypes who would illuminate his sardonic spirit behind a showcase of false fronts as sportsman, lover, spy, pilot, art aficionado, magician, attorney, surgeon, and on and on. In each of Snoopy’s masterfully seized, casually discarded roles, Schulz’s drawing became looser and rounder.

Snoopy was distinctly—defiantly, as far as Schulz was concerned—different from Mickey Mouse in one regard above all: where Mickey embodied the gutsy “little guy” of American myth in the 1930s, followed by the “brave regular Joe with a rifle” of the war years, and was therefore an adult, no matter how childish the worlds Disney pitched him into, Snoopy was distinctly a postwar, even a 1960s phenomenon. He was purely adolescent—grandiose, revolutionary, with a mind of his own and feelings to match. Often he acted like a very badly hurt person, except that, precisely because his innermost thoughts were open to view, his wound and shame were exposed for all to see. The more he tried to live by his own rules, and the louder Charlie Brown remonstrated (“Be happy with what you are!! ... YOU DUMB DOG”), the more human he became, as each experiment in living a life fully his own landed him right back on the floor of the doghouse, or in the parental lap, once more dependent.

As Snoopy’s rebellions developed, his personality as a player in the “Peanuts” repertory company evolved. In this world without adults, he now behaved for all intents and purposes like the one and only child—the real child—joyous one minute, cast down the next; now magnanimous, now petty; by turns critical, tactless, cunning—“a little selfish, too,” Schulz noted, identifying a whole range of controlling, testing qualities, starting with a “mixture of innocence and egotism.”

Snoopy's often treated Charlie Brown and his friends as if he were their intellectual superior; none of them could appreciate his talents, while he, in his turn, tolerated the foolish things they did. Lucy might play along with his fantasies (as mothers, or keepers, will), but she nonetheless let Snoopy know exactly who was in charge: “Any piranha tries to chomp me, I’ll pound him!!”

Snoopy is the one character in the strip allowed to kiss, and he kisses the way a child does: sincerely, and to disarm. As the rest of the “Peanuts” gang struggles to love and be loved, they find themselves stuck in the incompatible romantic pairings of classical comedy. Lucy’s definitive acceptance of Schroeder’s rejection, for example, would be a relief to both; instead, she subjects herself to ongoing cold, even brutal indifference. Snoopy, meanwhile, becomes the one between them, dancing on the piano, smitten by the beauty of the music, licensed to enact real feeling, inserting himself between the couple like a child whose family’s emotions are kept forever under restraint.

Throughout the late 50s, Snoopy’s doghouse was depicted in three-quarter view. Located on the side of Charlie Brown’s house, it had a peaked roof and a simple, unseen, one-room interior, and its owner’s name was written over the arched opening. It was nothing more than a real doghouse for a real dog. This rarely varied until early 1960, when, as the grand side of Snoopy’s personality began to stretch the dimensions of reality itself—one day he demanded to eat “on the terrace”; on another he installed an air conditioner—there came, Schulz later recognized, a turning point. Snoopy was now, he realized, “a character so unlike a dog that he could no longer inhabit a real doghouse.”

And so, on February 20, he turned the doghouse and presented it broadside, with Snoopy sleeping on the roof. Seen from this angle, powerfully alone in a horizonless world, dog and house merged to form a continuous line.

There would be occasional reversions to the old form, but never again would Snoopy be a dog in any conventional sense, and the rendering of his house would now be simplified to the point where sometimes, such as when Snoopy is composing at the typewriter, it almost loses its identity altogether. Seeking to keep the doghouse even marginally real, Schulz found that if he tilted the tip of his pen in a certain way, so that “a little bit of the ink drops below the line,” he could suggest the feel of wood in the roof and siding.

But it was more than elements of craft and design that demonstrated Schulz’s new conquests in the medium. The reader listening to Snoopy’s rooftop meditations was in fact overhearing Schulz’s thoughts, but instead of ascribing them to the cartoonist (as he might with Charlie Brown’s speeches), took the interior monologue for his own, somehow coming to believe that he was hearing his own jokes and quirks, worries and hopes.

"I'm torn," Schulz would say, “between being the best artistically and being the Number One strip commercially."

In A1 Capp (“Li’l Abner”) or Walt Kelly (“Pogo”), an intense editorialist was always at work. Jules Feiffer (“Feiffer”) could say crazy things because the reader understood him to be the ambassador from Greenwich Village. Mort Walker (“Beetle Bailey”) and Hank Ketcham (“Dennis the Menace”) were still gag cartoonists once more pulling the reader’s leg. But when Schulz began to let his strip’s dog think aloud on top of a doghouse, “all hell broke loose,” as Ketcham recalled it, for only a genius could speak for himself and have the world believe it was overhearing the voices on the edge of its heart.

For Snoopy to become a universal partner of the race with which he shared the planet—to leap over his current assignment as a radical individualist in the Minnesotan tradition—he had to become the hero, a tragicomic figure of such absurdly grand and revolutionary capacities that only he (and we) could see him transfiguring his doghouse into a flying machine sent aloft against the ultimate unseen enemy, the German ace Manfred von Richthofen, the infamous Red Baron. Snoopy threw himself so fully into an action fantasy that he by now had earned a title as powerfully mock-heroic as that of Cervantes’s Knight of the Rueful Countenance.

The World War I Flying Ace took off one day late in the summer of 1965 while Schulz was at the drawing board and his 13year-old son, Monte, came in with a model plane. Schulz’s recollection was that as they talked about Monte’s Fokker triplane it dawned on him to try out a parody of the World War 1 movies Hell’s Angels and The Dawn Patrol, which had gripped him as a boy at the Park Theater. He thought he might take off on the classic line “Captain, you can’t send young men up in crates like these to die!” And then it came to him: “Why not put Snoopy on the doghouse and let him pretend he’s a World War I flying ace?” But Monte always claimed that it had been he who first suggested the idea of Snoopy as the pilot. Schulz denied it just as frequently, conceding only in the last year of his life that Monte had “inspired it.” Either way, Schulz admitted, “I knew I had one of the best things I had thought of in a long time.”

Until now, “Peanuts” had been commentary on the world as seen and heard by Charles Schulz—recognizable, everyday problems transposed into the key of little-old-adult children. Unintentionally, Schulz’s themes raised the larger social questions that the civil-rights movement and Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society initiatives had put on the table: Who was entitled to happiness? Was the security of “owning your own home” and of “having a few bones stacked away,” as Snoopy put it, the birthright of prosperous white America only? Were black and poor people going to go on being excluded from the expectations spelled out by Schulz’s universal mantras for Happiness and Security and Home? When the Southern CONTINUED FROM PAGE 236 Christian Leadership Conference (S.C.L.C.) brought what was popularly known as the Poor People’s Campaign to Washington, D.C., to lobby Congress for a $30 billion anti-poverty bill, in May 1968, the placards that rose over Resurrection City on the Mall came all but directly from Schulz’s drawing board: “HAPPINESS IS ... A WARM DRY HOUSE ... NO RATS OR ROACHES .. . LOTS OF GOOD FOOD.”

CONTINUED ON PAGE 241

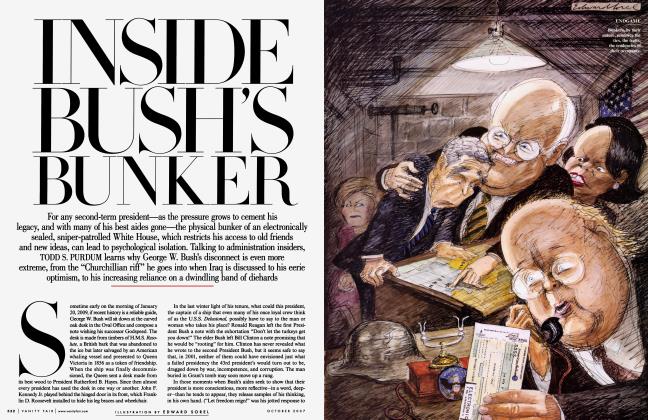

CONTINUED FROM PAGE 236

As doubt and distrust crept into people’s lives, Schulz’s plain commentaries on the comics pages and in Determined Productions’ small, square hardcovers set him up for a role he had never intended or wanted. “I’m not a philosopher,” he insisted, sometimes adding, “I’m not that well educated.” But the country had just reached the end of an era in which it considered itself to be the land that could boast the most distinguished philosophers. For 30 years, every high-school principal read Professor John Dewey, philosopher and educational reformer, or thought he or she ought to, and every college president salted his speeches with the aphorisms of George Santayana (“Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it”) and Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. (“Taxes are what we pay for civilized society”). But the era of Professor Santayana, Justice Holmes, and Dr. Dewey was closing, and middlebrow culture reassigned the role of philosopher. Henceforth, the general public would take “philosophy” in capsule form through novelists (Ernest Hemingway, Kurt Vonnegut), journalists (Murray Kempton, Russell Baker), social scientists (Marshall McLuhan, John Kenneth Galbraith), and cartoonists (Capp, Kelly, Schulz), although A1 Capp and Walt Kelly were drawing allegory that tartly commented on politics and society, and Schulz was creating the kind of myth in which everyone could find his or her own story: “Myths and fables of deep American ordinariness,” as the writer Samuel Hynes described “Peanuts.”

In a very midwestern way, Schulz reversed the American pattern of winners and losers, making a virtue of the fortitude required to endure blowing a hundred ball games in a row. The very notion embedded in You Can’t Win, Charlie Brown turned the eastern orthodoxies of American children’s literature inside out; in the creed of Louisa May Alcott, everything came out right in the end, but in “Peanuts” the game was always lost, the football always snatched away. In Charlie Brown’s world, the kite was not just stuck in a tree but eaten by it; the pitcher did not just give up a line drive but was stripped bare by it, exposed.

Now, in 1967, as Snoopy pantomimed people to themselves from the doghouse roof—no longer through the merely subversive impersonations of the 50s but acting out the Flying Ace’s fullfledged crusade—“Peanuts” acquired an explanatory as well as a descriptive character for thousands who burned draft cards and protested an incomprehensible war. While mission upon mission of B-52 bombers hammered North Vietnam’s capital and primary port cities, Snoopy’s mania, his single-minded pursuit of the enemy, and his hatred of losing epitomized the America haunted by an always victorious John Wayne, the postwar U.S.A. that was racing to beat the Soviets to the moon. As Snoopy soared—and danced—“Peanuts” once again led the culture. If the World War I Flying Ace mocked the martial spirit of a mere half-generation past, Snoopy’s spontaneous, soul-satisfying dances made him a genuine free spirit whose only commitment was to ecstasy itself. His flutterfooted step kept time to bliss itself, lifting him so high above the “over 30” concerns of his stripmates, he hardly seemed to notice that he was leaving reality—and petty old Lucy—in the dust.

Snoopy’s soul-satisfying dances made him a genuine tree spirit.

“Peanuts” in the new age of Snoopy was bolder but still quietly dissident, laying claim to joy, pleasure, naturalness, and a self-glorifying spontaneity without the ferocious exhibitionism that most radicals and rebels of the period deemed necessary to bring attention to their causes. Snoopy’s basic desire—to transcend his existence as a dog by altering his state of mind—typified a central urge of the era and caused alarm among the strip’s authority figures no less than its analogues did in the “real world.”

“The strip’s square panels were the only square thing about it,” reflected the novelist Jonathan Franzen, who, “like most of the nation’s ten-year-olds,” was growing up through those “unsettled season[s]” of the 60s by taking refuge in “an intense, private relationship with Snoopy”—a stronger attachment than that which the reader could have with any of the other “Peanuts” characters because Schulz was now making us Snoopy’s accomplices in transcendence. We alone can see what the Flying Ace is seeing; everyone else in the strip, even Charlie Brown, remains blind to the identity and miraculous feats of the Masked Marvel, the Easter Beagle, the World-Famous Astronaut, the World-Famous Wrist Wrestler, Joe Cool, Flashbeagle, “Shoeless” Joe Beagle, and the Scott Fitzgerald Hero.

Snoopy had his origins in Spike, the mutt of Schulz’s youth, whom Schulz called “the wildest and the smartest dog I’ve ever encountered,” and as long as Snoopy was treated as a pet—an eccentric, even a lunatic household dog—by the “Peanuts” gang, he evinced Spike-like behavior. But now he left the kids behind.

Lucy had fantasized about the White House, but in the presidential elections of 1968 and 1972, Snoopy was embraced by actual voters as a write-in candidate, prompting the California legislature to make it illegal to enter the name of a fictional character on the ballot. Brought down behind the German lines in the Red Baron sequences, he operated in a larger, more threatening world than did anyone in the secure suburbs of the “Peanuts” neighborhood. Unique among the gang, he was allowed, in romantic encounters with a “country lass,” to enter just ever so slightly into adult sexuality—Schulz once again having it both ways, for Snoopy also kisses like a child.

Back home—again, uniquely—he had adult possessions, and not just books, records, and pinking shears. The multi-level rooms under the peaked roof of the doghouse now included a front-hall rug, a cedar closet, a lighted pool table, a stereo, and a van Gogh which, after a fire, was replaced by an Andrew Wyeth. Snoopy’s tastes were like those of every college kid in 1966, who, with a folk guitar and a tattered paperback copy of Herman Hesse’s Siddhartha, had hung the dorm room with a Wyeth print—a magical-realistic picture unsettling because it transcended the ordinary rural life it seemed to be faithfully depicting—as an emblem of the searching, melancholy, considered life toward which he or she believed him/herself, perhaps the whole troubled world, to be tumbling.

This was the first time in the comics that an animal had trumped the humans. Never before had an animal taken over a human cartoon, and “it did more than change Pea- nuts,” said Walter Cronkite, “it changed all comics.” Schulz’s fellow cartoonists read and reread the Red Baron episodes to figure out how Schulz was getting away with it. His rival Mort Walker looked on, dismayed. The gag-minded creator of “Beetle Bailey” had been able to follow along with Schulz when Snoopy was perched in a tree, pretending to be a vulture. But, a dog... flying a Sopwith Camel which was actually a doghouse, which he couldn’t sit on anyway? “That’s when I realized I didn’t know anything about the comic business,” said Walker. “What does a dog know about World War One and the Red Baron? Where did he get the helmet?” Most astonishing of all: what was Schulz doing showing actual bullet holes in a doghouse? “Good golly,” Walker said to himself, “this has gone beyond the tale.”

Hidden from no one except Charlie Brown and his friends, the visual and verbal vocabulary of Snoopy’s fantasy universe became common to both the younger and older generations throughout the 60s. One of the very few “enemies” that Americans could agree on in those years was the Red Baron. In college fraternities and motorcycle gangs, rock groups and combat units, communes and airmen’s hangouts, people nicknamed one another Snoopy and Red Baron and Flying Ace and Pig-Pen. (This last category included the Grateful Dead’s keyboardist Ron McKernan.) There was even a San Francisco band calling itself Sopwith Camel.

Free spirits in the counterculture asked loudly and roguishly the very question that Schulz had been whispering in mainstream comics pages for more than 10 years: What would it be like to feel happy? A 1967 Time cover story had cited Schulz’s characters as “hippie favorites” and placed Schulz in his 18-acre country estate on Coffee Lane in Sebastopol, California, as the admired neighbor of the infamous Morningstar commune. In 1968, six years after Schulz’s microbook Happiness Is a Warm Puppy had become a mega-best-seller, John Lennon retorted with a song on the Beatles’ White Album: “Happiness Is a Warm Gun.” And two years after Schulz wrote the scene in A Charlie Brown Christmas in which Linus decides that Charlie Brown’s wretched little tree is “not a bad little tree—all it needs is a little love,” the Beatles hammered the same message around the world: “All You Need Is Love.”

The lexicon of “Peanuts” filtered through the culture, middle to top, top to bottom. As “security blanket” found its way into Webster’s dictionary and “Happiness Is ... ” into Bartlett’s Familiar Quotations, “Good grief!” became the allpurpose refrain of Candy Christian, the innocent, infinitely corruptible heroine of 1964’s most notorious book, Candy, an erotic satire written by the expatriate hipsters Terry Southern and Mason Hoffenberg. The next summer, members of the Jefferson Airplane heard that children in the neighboring studio were recording the voices of the parentless “Peanuts” characters for a Christmas television special and, treating the Charlie Brown cast as if they were an enlightened prophetic microcosm of the whole youth culture, went over to get their autographs.

Schulz called Snoopy 'the dream to be the superhero.”

Unbeknownst to Schulz, another rock group, the Royal Guardsmen, a sextet from Ocala, Florida, was on its way to selling three million copies of a hit single called “Snoopy vs. the Red Baron” (“Finally, a hero arose / A funny-looking dog with a big black nose... ”). Schulz heard it only when a friend remarked, “Great song you wrote.” As soon as cartoonist and syndicate had been cut into the royalties, the group added a string of sequels and produced four LPs. On one they loosely fitted an anti-Vietnam message to the “fascinating allegory” of Snoopy and the Red Baron’s calling the World War I Christmas truce in No Man’s Land, with which the Guardsmen intended “basically [to] expose the futility of neverending conflict.”

As early as 1959, two Convair B-58 supersonic bombers, designated Snoopy-1 and Snoopy-2, took to the skies with their namesake painted on their noses “in his most supersonic pose,” as a Convair executive wrote to Schulz. By the mid-60s, whole squadrons of F-100 pilots were taking their craft into action in flight suits decorated with diamond-shaped patches featuring the Flying Ace; officials at NASA named Snoopy the symbol of a new safety and morale-building program.

From 1966 to 1969, Snoopy could be found pursuing—or being pursued by—the Red Baron wherever America explained itself to itself, whether in a rock formation on the rim of the Grand Canyon, nicknamed “Snoopy Rock,” for its resemblance to Snoopy sleeping on his doghouse, or as a Goodyear blimp or gigantic balloon in Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade. In form and function, the doghouse could now take Schulz and his beagle anywhere the nation was going, including the moon. And on March 10, 1969—four months before man’s first lunar landing—the World-Famous Astronaut was dispatched into space.

Two months later, in a command module named Charlie Brown and its lunar module, Snoopy, Commanders Eugene A. Cernan and John W. Young, U.S. Navy, and Colonel Thomas P. Stafford, U.S. Air Force, piloting the Apollo 10 spacecraft on a scouting mission to the moon, descended to within almost eight and a half nautical miles of the Sea of Tranquility in a final rehearsal for the history-dividing Apollo 11 landing, in July. To the astronauts, Snoopy was more than a mascot: as “the only dog with flight experience,” he served as guardian and guide. About halfway to the moon, 128,000 miles from Earth, Cernan held up a drawing of Snoopy, goggled, helmeted, and scarved, to the color TV camera on board for transmission back home. “I’ve always pictured Snoopy with the old World War One aviation helmet and goggles and silver scarf, and I think we sort of fashioned ourselves that way in those days,” Cernan later recalled, NASA estimated that more than a billion viewers all over the world saw Snoopy at that moment.

On May 22, after the two spacecraft recoupled in a tense docking procedure on the far side of the moon, Mission Control, in Houston, broke out a large cartoon showing Snoopy kissing Charlie Brown, and newspapers around the world ran banner headlines: DOPO LA MISSIONE VICINO ALLA LUNA: “SNOOPY” RITROVA “CHARLIE brown”—and when they splashed down in the Pacific: “SNOOPY” SAFE AFTER PERILOUS MOON TRIP.

'Peanuts” had sprawled out of the old comics page to hit a new nerve. “Something was touched,” the writer Renata Adler wrote years later. Never again would a cartoonist and his characters so consistently capture so much of the culture and the times. In the previous decade, “Pogo” had identified the true enemy power in McCarthyism: He is us. But “Pogo,” for all its satiric cunning, remained fixed in the McCarthy-Stalin era. Now, in the 60s, “Peanuts” was the one imparting messages and meanings to the hurtling moment, with one significant difference: instead of ending after two decades, “Peanuts” had just begun.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now