Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowOut to Lunch with ANDRE SOLTNER

ET CETERA

AMERICNS FIRST CELEBRTTY CHEF GIVES A LESSON IN MAKING THE PERFECT OMELET

CONVERSATION

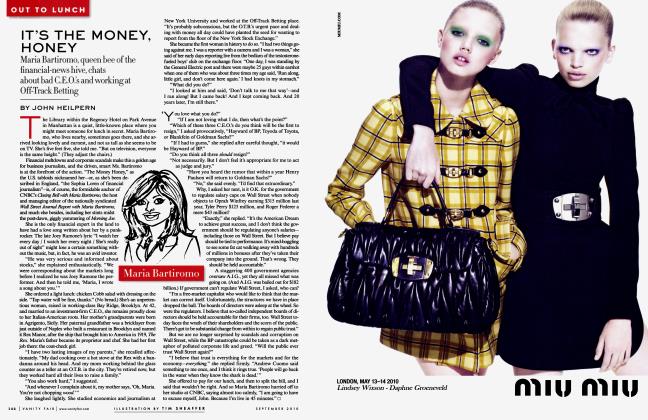

JOHN HEILPERN

A ndre Soltner, who was America's first superstar chef before the battling celeb chefs of the Food Network were invented, very kindly agreed to meet before our lunch to teach me how to make an omelet.

The revered Soltner, who presided over Lutece, in New York, for 34 years his retirement, in 1994, was mourned on the front page of The New York Times— believes that to be a great chef you must be able to make a perfect omelet. On the other hand, I would be happy enough to be able to make one that didn't come out as scrambled eggs.

Born in Alsace, France, in 1932, MiSoltner is now one of the deans of the International Culinary Center, in downtown Manhattan, where he still teaches master classes in classic French cooking. He greeted me there, a benign figure in his pristine white chefs uniform, standing behind the hot stove of one of the Center's glass-walled kitchens. He had already made an omelet.

"The shape of a cigar, you see?" he said. (He still has a marked Gallic accent despite his many years in the U.S.) "Beautiful! And no wrinkles. Smooth. Inside haveuse—soft, but not runny. You don't have to taste it. Just by the look you know it's good. If you like it a little brown, spread a little butter on top and put it under a hot broiler—but only for a second."

Why is cooking an omelet his supreme test of a chef? "Because it takes only two minutes. You watch the technique—but technique without heart is no use. It's fast and it's very simple. If a chef can't do it, forget him."

He began the lesson, and two minutes later he had effortlessly made the perfect omelet. (You can see him doing it on YouTube.) "Now take off your jacket," he said, "and you make one."

"This is going to be a total embarrassment," I replied.

"Don't be scared. You write better than I do, you know?" Andre Soltner, you will have gathered, is a most charming man. But he is strict, when need be.

"Oops," I said from the get-go, when I cracked an egg and shell fell into the bowl along with it. "That's all right," he said, fishing it out. But things got fraught.

"Faster! Faster!" he ordered. "Don't doubt!" "Tsk-tsk!" "Shake the pan more!" "More!""Now gently!" Until, mercifully, I eventually tapped the omelet onto the plate, as instructed, where it lay in need of repair.

Chef Andre scored it a generous 7 out of 10—"or maybe 6 to 7." But, still, at least it wasn't scrambled eggs.

We then lunched at L'Ecole, the Culinary Center's well-regarded restaurant, where its top trainee chefs cook for the paying public. (It was full that day.) He ordered a spritzer and talked about the surprisingly bleak possibilities of cooking well when he first came to work here, in the early 1960s. His four-star Lutece was originally one of the pioneering haute cuisine restaurants of New York—along with Le Pavilion, La Caravelle, La Cote Basque, and La Grenouille—that defined an entire era. But it wasn't easy.

"All the food was frozen or canned in those days. There was no fresh produce! It turned out that you could get fresh chanterelle mushrooms in Oregon, but they sold them to Germany, who canned them and sold them back to America. It's unbelievable, no?"

What does he think of waiters who nowadays inquire if we have any allergies?" "We are not doctors! But if you have an allergy, you should let the chef know." We live in litigious times, he reminded me, and restaurants are now routinely sued for practically anything—including lawsuits from customers who fall off barstools.

"Please enjoy," said our waiter. Chef Andre had ordered a glazed-pork-belly tenine followed by a cassoulet tasting. He eats for pleasure, in moderation.

What does he think about molecular gastronomy? "I better don't think! We are not scientists either! We teach molecular at the school, but not me. I'm an old-timer." His roots remain unapologetically grounded in the classical French tradition of Escoffier. "People say molecular is fantastic," he went on. "And, you know, people say Picasso is a great, great artist. But a common guy like me looks at a Picasso and he says, 'I don't understand.' One hand is here, one eye is there! It's now the same thing with cooking—you understand?"

Like pate on your plate, I suggested, which looks like a lump of coal, but is considered a postmodern art form. "But we are not artists," he emphasized (though he's been frequently described as one). "We are craftsmen. An artist paints or sculpts a work of ait, but many times it's not so great and he knows this. So perhaps he stalls again a week later, or perhaps he decides not to sell. We cannot do that. We have to be good every s time, every day of the week. And we g must deliver the meal to your table g now—not tomorrow! It takes training | and technique and taste. It's a craft."

At which the masterful Andre Soltner, son of a cabinetmaker, looked un7 derstandably proud just the same.

WE ARE CRAFTSMEN

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now