Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

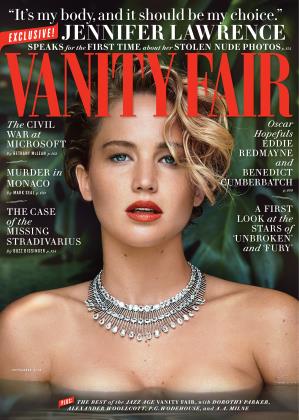

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowVANITY FAIR'S JAZZ AGE COCKTAIL

To wind up the magazine's centennial,V.F. is publishing a unique treasury from its Jazz Age incarnation. In this adaptation, P. G. Wodehouse, Dorothy Parker, A. A. Milne, and Walter Lippmann, amony, others, sparkle as if now

THE V.F. CENTENNIAL

Over the past year, we've been celebrating our 100th anniversary as a magazine. And this month, to honor the Jazz Age incarnation of Vanity Fair, we are publishing a first-of-a-kind treasury, Bohemians, Bootleggers,Flappers,and Swells: The Best of Early Vanity Fair(Penguin Press). The anthology showcases stories published in these pages from 1914 to 1936 by a murderers' row of literary figures who were frequent V.Fcontributors: from D. H. Lawrence to Colette, Robert Benchley to E. E. Cummings, Carl Sandburg to Langston Hughes, Gertrude Stein to Jean Cocteau. The book provides an inebriating swig from that great cocktail shaker of the Gatsby era, comprising 72 classic pieces in which unforgettable writers offer their views on how to live well in a fast-changing age. Herewith, some excerpts.

P. G. WODEHOUSE The Physical Culture Peril

It is alleged by scientists that it is imposI sible for the physical culturist to keep _1_ himself from becoming hearty, especially at breakfast, in other words a pest. Take my own case. Once upon a time I was the most delightful person you ever met. I would totter in to breakfast of a morning with dull eyes, and sink wearily into a chair. There I would remain, silent and consequently inoffensive, the model breakfaster. No lively conversation from me. No quips. No cranks. No speeches beginning "I see by the paper that..." Nothing but silence, a soggy, soothing silence. If I wanted anything, I pointed. If spoken to, I grunted. You had to look at me to be sure that I was there. Those were the days when my nickname in the home was Little Sunshine.

Adapted from Bohemians, Bootleggers, Flappers, and Swells: The Best of Early Vanity Fair, edited by Graydon Carter, with David Friend, to be published this month by Penguin Press; © 2014 by Conde Nast.

Then one day some officious friend, who would not leave well alone, suggested that I should start those exercises which you see advertised everywhere. I weakly consented. I wrote for the small illustrated booklet. And now I am a different man. Little by little I have become just like that offensive young man you see in the advertisements of the give-younew-life kind of medicines—the young man who stands by the bedside of his sleepy friend, and says, "What! Still in bed, old man! Why, I have been out with the hounds a good two hours...." At breakfast I am hearty and talkative. Throughout the day I breeze about with my chest expanded, a nuisance to all whom I encounter. I slap backs. My handshake is like the bite of a horse.... It is the same spirit which led Vikings in the old days to burst into song when they had succeeded in cleaving some tough foeman to the chine.

Naturally, this has lost me a great many friends.

STEPHEN LEACOCK

Are the Rich Happy?

December 1915

I have never known, I have never seen, I any rich people. Very often I have _l_ thought that I had found them. But it turned out that it was not so. They were not rich at all. They were quite poor. They were hard-up. They were pushed for money. They didn't know where to turn for ten thousand dollars.

In all the cases that I have examined this same error has crept in. I had often imagined, from the fact of people keeping fifteen servants, that they were rich. I had supposed that because a woman rode down town in a limousine to buy a fifty dollar hat, she must be well to do. Not at all. All these people turn out on examination not to be rich. They are cramped. They say it themselves. Pinched, I think is the word they use....

Mr. Spugg... is a self-made man and he has told me again and again that the wealth he has accumulated is a mere burden to him. He says that he was much happier when he had only the plain simple things of life. Often as I sit at dinner with him [at his club] over a meal of nine courses, he tells me how much he would prefer a plain bit of boiled pork, with a little mashed turnip. He says that if he had his way he would make his dinner out of a couple of sausages, fried with a bit of bread. I forget what it is that stands in his way. I have seen Spugg put aside his glass of champagne,—or his glass after he had drunk his champagne,—with an expression of something like contempt. He says that he remembers a running creek at the back of his father's farm where he used to lie at full length upon the grass and drink his fill. Champagne, he says, never tasted like that. I have suggested that he should lie on his stomach on the floor of the club and drink a saucerful of soda water. But he won't.

DOROTHY PARKER

Our Office: A Hate Song

May 1919

An Intimate Glimpse of Vanity Fair En Famille

I hate the office;

It cuts in on my social life.

There is the Ait Department;

The Cover Hounds.

They are always explaining how the photographing machine works.

And they stand around in the green light And look as if they had been found drowned. They arc forever discovering Great Geniuses; They never fail to hnd exceptional talents In any feminine artist under twenty-hve. Whenever the illustrations arc late The fault invariably lies with the editorial department.

They are always rushing around looking for sketches,

And writing mysterious numbers on the backs of photographs,

And cutting out pictures and pasting them into scrapbooks,

And then they say nobody can realize how hai'd they are worked—

They said something....

I hate the office;

9 > It cuts in on my social life.

A. A. MILNE

My Autobiography

January 1920

A few years a§° I published a book. |« /% That is to say, I wrote the thing, and 19 J_ my agent induced a publisher to ac14 cept it, and the publisher tried to induce the public to buy it. We had quite a fair success; we sold a good seven copies. However, it is generally agreed among actuaries and others that we might have had a really big success, we might have sold nine or even ten copies, but for an unfortunate occurrence. I shall explain what happened.

At about the time that the book was accepted I wrote a story which appeared in an American magazine. I had never written in an American magazine before, and though my name is of course a household word in the uninhabited parts of China, it was felt that I needed a special introduction to the people of New York. My agent suggested, therefore, that I should write a short life of myself—two or three hundred words, say—explaining who the dickens I was, in order that the editor might print this alongside my story, as a sort of explanation why he did it....

Naturally, when I sat down to write my life I began to wish that I had lived a better one. But it was then too late; the copy had to be in by Friday. I told them where and when I was born, where I was educated ... and what made me first begin to write. I described my marriage, my permanent address and the regiment to which I had attachedmyself for the war. I mentioned my travelbook, "Half an Hour in the Malay Archipelago," and my detective-story, "The Crimson Cough." I wrote three hundred words all about myself—a fascinating subject—and sent them to my agent, and he wrote back to thank me, and said that he supposed it would have to do. But he seemed to be a little disappointed.

A week went by, and then I heard from my agent again. My book would be coming out soon, my first book in America. Widely quoted as I was on the desert islands of the Pacific, I was not (he opined) a very familiar personality to the library-subscribers of New York. The publisher suggested therefore that I should write a short life of myself—two or three hundred words, say—explaining who the devil I was, in order that he might circulate it in advance as a warning of what was coming.

So I sat down to write my life. It was rather a bore doing it again, and I wished that I had kept a copy of what I had written the week before. However, it was no good worrying about that now. Selecting a clean piece of paper, and dipping my pen in the ink, I told them where and when I was bom, when I was educated and what made me first begin to write. I described my marriage, my home, my military experiences. I mentioned my detective-story, "The Crimson Cough," and my travel-book, "Half an Hour in the Malay Archipelago." I wrote three hundred words all about myself—a subject still fascinating, although some glamourhad worn off—and I sent them to my agent.

The next morning he called me up on the telephone. He was very much upset.

"I say, really!" he expostulated. "This won't do at all."

"Why, what's the matter?"

"My dear fellow," he said, reproachfully, "this is the same life as the other one."

He thinks that, but for this, we might have sold nine, or even ten, copies of the book.

SHERWOOD ANDERSON

Hello, Big Boy

[on America's 150th Birthday]

In the early days, when the towns and citI ies were widely scattered, when it was a _l_ difficult slow job to get from one place to another, when the forests spread away on all sides, men lived in comparative isolation and were thrown back upon themselves. Those who were able to bearsuch a life at all became strong individuals. They were bold, half mystics, believing divinely in themselves and their own dogmas, thought out in lonely places, who infected other men with their dogmas because they were strong men.

Then [came] the machine, the herding of men into towns and cities, the age of the factory. Men all began to dress alike, eat the same foods, read the same kind of newspapers and books. Minds began to be standardized as were the clothes men wore, the chairs they sat on, the houses they lived in, the sheets they walked in.

WALTER LIPPMANN

Blazing Publicity

September 1 927

T he publicity machine will have become mechanically perfect when anyone anywhere can see and hear anything that is going on anywhere else in the world. We are still a good long way from that goal, and the time has not yet come when the man in quest of privacy will have to wear insulated rubber clothing to protect himself against perfect visibility.

[In the interim] we have made great progress_We can transmit sound over great distances. We can transmit photographs_We

can make moving pictures that talk. Tomorrow we shall have television.... These inventions combined with the facilities of the great news gathering organizations have created an engine of publicity such as the world has never known before. But this engine has an important peculiarity. It does not flood the world with light. On the contrary it is life the beam of a powerful lantern which plays somewhat capriciously upon the course of events, throwing now this and now that into brilliant relief, leaving the rest in comparative darkness.

ALEXANDER WOOLLCOTT

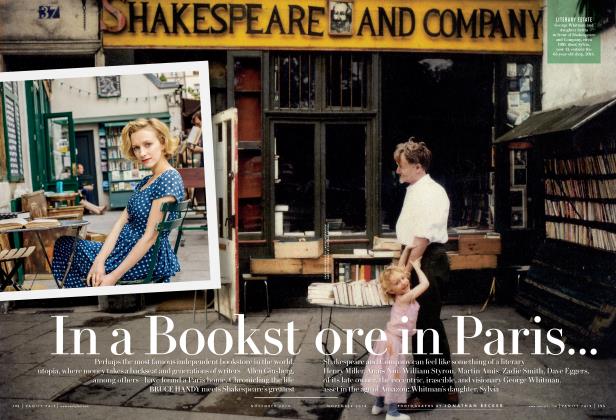

If You Are Going to Antibes

July 1929

T hey tell me there is a woman living in a small frame house in a Montana village who has expressed no intention whatever of going to Antibes this summer. I have heard no explanation of this bizarre uniqueness of hers, have received, as yet, no

details to account for what does seem at first blush a somewhat too studied effort to be conspicuous. Perhaps she has a morose aversion to human society. Then again she may be merely destitute. Or, haply, bedridden.

The tendency of ... human society to gather each summer in a kind of hilarious, moist and irresponsible congestion at that once obscure point on the Riviera is a quite recent deflection in the drift of peoples over the face of the earth....

Two or three years ago it dawned abruptly on the world's floating population that whereas the Riviera was pleasant enough in Winterpreferable, certainly, to Archangel or Sitka, or even Utica, New York it is incomparably more agreeable in the Summer, when the skies arc always smiling and the malachite green of the Mediterranean invites you to the most delightful swimming to be had anywhere in the world. How abrupt this discovery was, I myself can testify, for when I was in Antibes in June, 1925, some six guests—people like Roland Young and the progeny of Robert Benchley and other persons of no social importance whatever—rattled around in the vast spaces of the Grand Hotel du Cap, their footfalls echoing

hollowly in its deserted corridors. Only three years later I lived to see the once abject management explaining patiently to one Bernard Shaw that they had no room for him.

DAVID CORT

A Stock Market Post-mortem

January 1930

What distinguished the recent collapse of the stock market from other American panics, multiplying the total hysteria but deadening the individual shock, was that it was a thoroughly democratic affair: everybody was in it.... But since, in this instance, Wall Street was coincident with Main Sheet, it was super-Wall Sheet, nightmare Wall Street.... Oddly enough, the

ALLEGE TAEMEY

Golden Swank

February 1936

newspapers under-played it, even though they gave it streamer headlines day after day. They were compelled to undeiplay it. If they had reproduced starkly the utter bottomlessness of the thing, anything might have happened.

Over in the dumps by the Third Avenue Elevated, John Perona runs | El Morocco, the smartest night¾¾ club of them all.... o

His El Morocco at two o'clock on a winter's morning is a dream of a nightclub, s 0

smoky, stifling, with an electricity of gayety, starting from no known socket. Tables 1 o completely cover the dance floor, artfully sU arranged by Perona into a lovely crossfh section of night club aristocracy. In clumps t ⅞

the debutantes sit, calling out from table to table, laughing their high whinny. In fur^ | ther clumps the kept women flash with dia11 monds almost as big as those of the society 81 girls. There arc always actresses, movie stars, | ⅛: models. Somewhere in the center wanders Perona with his sixth Scotch and Perrier, | g flashing his white smile. □ II

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now