Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowMADE IN MANHATTAN

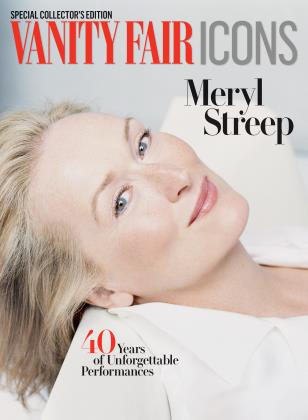

A BRIEF BUT HEADY FEW YEARS IN THE NEW YORK THEATER SCENE OF THE 1970S—A PERIOD THAT TOOK HER FROM THE EAST VILLAGE AVANTGARDE TO SHAKESPEARE IN THE PARK—SET MERYL STREEP ON A PATH FOR STARDOM. BIOGRAPHER MICHAEL SCHULMAN RECOUNTS ALL THE INTIMIDATING AUDITIONS, STUNNING PERFORMANCES, AND EXTRAORDINARY RELATIONSHIPS THAT MADE IT POSSIBLE

MICHAEL SCHULMAN

The summer of 1975 was a brutal time to start an acting career, and the graduates of the Yale School of Drama had that drummed into their heads. The country had been slogging through a recession, taking the entertainment industry and all of New York City down with it. Times Square had devolved into a wasteland of garbage and strip joints. Broadway theaters were empty, or being turned into hotels. Even day jobs were hard to come by. As one Yale actress sighed to the New Haven Register shortly after graduation, "Unfortunately, the jobs selling gloves at Macy's are getting as hard to find as acting jobs."

The math was bleak: Six thousand more degrees in dramatic arts had been awarded across the country than the previous year. Many graduates would try their luck in New York, while others fanned out to regional theaters. One Yale actor was off to Massachusetts to operate a kite shop.

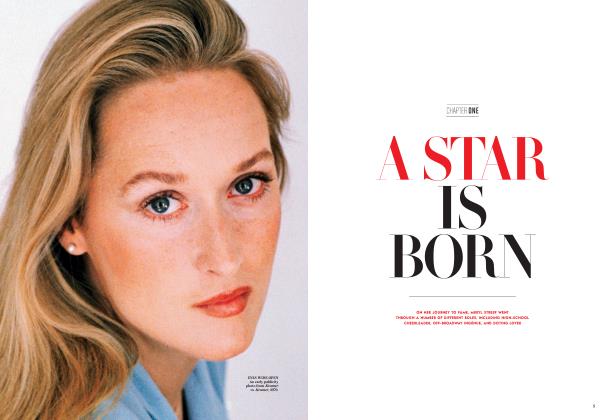

And where was Meryl Streep, the undisputed star of the class of 1975? Meryl Streep, who had two degrees, $4,000 in student loans, and almost no professional credits to her name? Stuck on the interstate from Connecticut, an hour late to meet Joseph Papp, one of the biggest producers in New York City.

I'm 26, she had told herself. I'm starting my career I better make it next year

A lot was riding on this one, because she had already screwed up. Before graduation, the acting students had taken a trip to New York to audition for the Theatre Communications Group, which placed young actors at regional theaters across the country. The TCG audition was so important that Yale offered a special class on it. The drama students would be up against their counterparts from Juilliard and NYU, and whoever made it through the New York round would be sent to finals in Chicago. Impress the panel, and you might get hired to join a company in Louisville or Minneapolis. It wasn't New York, it wasn't Hollywood, but it was a job.

Meryl stayed over in New York the night before the audition. When she woke up the next morning, she looked at the clock and went back to sleep. She just didn't go. She couldn't stand the idea of going up against the same seven or eight people again. Perhaps she also knew that she didn't belong in Louisville. As she drifted back to unconsciousness, she could hear her classmates' voices in her head: "Gawd, where's Meryl? Oh, man, she's really fucked herself now!"

(FROM THE BOOK HER AGAIN: BECOMING MERYL STREEP BY MICHAEL SCHULMAN. COPYRIGHT © 2016 BY MICHAEL SCHULMAN. REPRINTED BY PERMISSION OF HARPER, AN IMPRINT OF HARPERCOLLINS PUBLISHERS.)

Was she finished? Not quite. Because soon after, Milton Goldman, the head of the theater division at the talent agency ICM, called up Rosemarie Tichler, the casting director at the Public Theater.

"I want you to meet someone," he told her. "Robert Lewis, the acting teacher at Yale, said she's one of the most extraordinary people he's ever taught."

"If Robert Lewis says that, I'd be happy to meet her," Tichler replied from her office in the East Village. Of course, this could be Milton exaggerating, she told herself.

Days later, Meryl auditioned for Tichler at the Public. "I just knew she had great beauty, she had a lightness of touch," Tichler said. "She had grace."

Tichler was casting Trelawny of the ' 'Wells, " a Victorian comedy by Arthur Wing Pinero, about the ingenue of a theater troupe who gives up the stage for marriage. The show would go up at the Vivian Beaumont at Lincoln Center, which had lately become an outpost of the New York Shakespeare Festival, a sprawling entity that included the Public Theater and Shakespeare in the Park. Tichler was looking for someone to play Miss Imogen Parrott, an actress who doubles as a theater manager. She had to be charming but authoritative, good with money and at telling people what to do. Tichler thought back to that crackling Yale actress and called her in for the director, A. J. Antoon.

But Antoon wasn't sold. He liked Meryl, but he liked other people, too. At her second audition at the Public, he hadn't seen what Tichler had seen—that one-in-a-million thing. Tichler kept pushing, but Antoon's wasn't the opinion that really mattered. The person who mattered was Joe Papp, the man who founded the New York Shakespeare Festival and ran the Public and employed just about half of the actors, playwrights, and directors in New York City.

Meryl was still in Connecticut and couldn't make the normal audition times, so Tichler and Antoon had her come in for Papp after hours. Seven o'clock turned to eight o'clock, and there was no Meryl Streep. Papp was getting restless—patience wasn't his strong suit—and the sky was getting dark. As he paced, Tichler nervously kept the conversation going. She wanted him to see this girl. Where in God's name was she?

Meryl zoomed down the highway in a borrowed car with Joe "Grifo" Grifasi, a fellow actor she'd been working with over the summer at the Eugene O'Neill Theater Center in Waterford, Connecticut. As Meryl drove and lit cigarettes, Grifo held the script and ran her lines. Whiteknuckling the wheel at 85 m.p.h., she calmly recited her speeches as he fed her cues, the two of them enveloped in

a Marlboro cloud. As they passed New Haven, Grifo imagined the Variety headline: "Dead Thesps, Dreams Dashed in High-Speed Curtain Call."

By the time they pulled up to Lafayette Street—alive—she was despondent. They were so absurdly late. They 're not going to hire me, she thought. I'm going to go, but it's doomed. She got out of the car while Grifo kept the motor running, like a getaway driver in a bank heist. The air was sticky, and she didn't want to start sweating, so she walked instead of ran. Not that it mattered. She was doomed.

But that's not what Rosemarie Tichler saw. Having desperately tried to keep Papp occupied as the clock ticked, she was about to give up when she stepped outside and took one last look down the street. There was Meryl Streep, an hour and a half late, but walking.

TICHLER WATCHED IN AWE. "95 PERCENT OF ACTRESSES WOULD GET HYSTERICAL, RUT SHE JUST HANDLED IT."

She swept Meryl inside and introduced her to Joe. After quickly apologizing for being late, she went right into the scene—no time for fuss.

Tichler watched her in awe. Here she was, fresh out of drama school, meeting the kingpin of downtown theater for the first time, late for a callback for a major part at Lincoln Center. "95 percent of actresses would get hysterical, but she just... handled it," Tichler recalled.

When she left, Tichler let a momentary silence linger. Then she turned to Papp and said: "That's it, right?"

Outside on the curb, Meryl hopped back into the car. She finally breathed. They would have to book it back to Connecticut.

"I saw Joe Papp," she told Grifo.

And?

"He liked me."

She was right. Meryl Streep had just clinched her first role on Broadway. And she hadn't even moved to New York.

FOUR YEARS BEFORE Woody Allen romanticized it in Manhattan, New York City was in a rut. Budgetary foibles and urban decay had left a miasma of neon, sleaze, and crime. Murders and robberies had doubled since 1967. Under Mayor Abraham Beame, the city was hurtling toward bankruptcy. In July, 1975, the city's sanitation workers went on a wildcat strike, leaving garbage to pile up and fester in the heat—people were worried about the health risks of flies.

Filmmakers like Sidney Lumet and Martin Scorsese captured the grime and corruption in Mean Streets, Serpico, and Dog Day Afternoon, the last of which opened on September 21, just as the muggy "dog days" of summer were turning into a ruddy fall. Soon after, the city was denied a federal bailout, and the Daily News ran the immortal headline "Ford to City: Drop Dead." Like a dirt-smudged orphan, New York was on its own.

For Meryl Streep, who had just moved to Manhattan, it was the place to be. She had a job on Broadway and a room on West End Avenue, in an apartment she shared with Theo Westenberger, a photographer friend she had met at Dartmouth. Westenberger would become the first woman to shoot the covers of Newsweek and Sports Illustrated. For now, she found an ideal subject in her roommate, whom she shot leaning on a television in a kimono, or straddling a stool in a leopard-print jumpsuit.

Soon after, Meryl got her own place a few blocks away, on West 69th Street, just off Central Park West. The neighborhood was rough—there were drug deals on Amsterdam Avenue all the time—but it was the first time she was living alone, free of roommates or brothers. However hazardous, she found the city glamorously lonesome.

"I got three bills a month—the rent, the electric, and the phone," she would recall years later. "I had my two brothers and four or five close friends to talk to, some acquaintances, and everybody was single. I kept a diary. I read three newspapers and the New York Review of Books. I read books, I took afternoon naps before performances, and stayed out till two and three, talking about acting with actors in actors' bars."

And, unlike much of New York City, she was employed.

At her first reading of Trelawny, she was petrified. The company was large, with veteran stage actors like Walter Abel, who was born in 1898, the same year the play premiered. But there was a younger set, too. A tightly wound 22-year-old Juilliard dropout named Mandy Patinkin was also making his Broadway debut. So was the bug-eyed character actor Jeffrey Jones. At 29, the broad-faced Harvard graduate John Lithgow was on his third Broadway show. And, in the title role of Miss Rose Trelawny, the bee-voiced, auburnhaired Mary Beth Hurt was on her fourth.

Mary Beth was also 29, having come out of NYU's drama school in 1972. Her marriage to William Hurt, a drama student at Juilliard, had imploded just as she was finding her professional footing. In 1973, Papp cast her as Celia in As You Like It in Central Park, and during rehearsals she became so distraught that she checked into the psych ward at Roosevelt Hospital. "I thought that I had really failed," she said later, "that I was supposed to be the perfect wife." Papp called her every day at the hospital, saying, "We'll hold the role open for you as long as we can. Please come back."

"Once Joe loved you—and it really did feel like love; it didn't feel like trying to use someone—he loved you forever," Mary Beth said. After three days, she checked herself out and went on as Celia.

At the read-through of Trelawny, Meryl was trembling. At one point, she realized her upper lip was wiggling, completely independent of the lower one. A. J. Antoon had reset the British play in turn-of-the-century New York, and smack in the middle of one of her lines, she heard a booming voice: "Do a Southern accent."

It was Joe Papp.

" Yessuh, " she said, instinctively modeling her drawl on Dinah Shore's. ("See the U.S.A. in your Chevrolet... ") And suddenly her character started to make sense—an ingenue getting on in years, shifting from Southern belle to savvy theater manager, able to boss people around. Joe was right.

"The curvaceous, desperately subtle flirtation in the cadences moved me toward a way of holding myself and of moving across the room, a way of sitting, and above all an awareness, because a Southern accent affords self-aware self-expression," she said later. "You shape the phrase. Not to get too deep into it, it was a valuable choice and it was not mine, it was his and I still don't know where the hell he got the idea. This is the essence of his direction. He's direct. Do it, he says."

John Lithgow had met Meryl a few months earlier, at a reading of a play by a Harvard friend of his—something about hostages in Appalachia. He had noticed "a pale, wispy girl with long, straight, cornsilk hair" and an odd name. "She appeared to be in her late teens," he wrote in his memoir, Drama: An Actor's Education. "She was so shy, withdrawn, and self-effacing that I couldn't decide whether she was pretty or plain. The only time I heard her voice was when she spoke her lines. She had a high, thin voice and a twangy hillbilly accent. She was so lacking in theatrical airs that I surmised that perhaps she wasn't an actress at all." He wondered whether the play was actually based on her.

When he spotted her at the first rehearsal of Trelawny of the "Wells, " she was like a different person, animated and eager and confidently beautiful. As usual, she wasn't letting her nerves show. "I'd been watching actors act my whole life," he recalled. "I wasn't easily taken in. But when I'd mistaken her for a hayseed hillbilly at that play reading a few months before, either I had been a myopic fool or this young woman was a brilliant actress."

OCTOBER 15,1975! opening night of Trelawny of the "Wells. "Meryl was backstage at the Vivian Beaumont, waiting to go on. Her upper lip, once again, was trembling. She willed it to stop, but it was no use. She tried not to think about the critics, who were out there scowling in the dark. She told herself: My student loans are going to be paid oflf!

Michael Tucker, the 31-year-old actor playing Tom Wrench, was already onstage. He was nervous, too. Meryl thought of the swanning, confident woman she was about to play, and walked onstage.

"Well, Wrench, and how are you?" was her first line on Broadway.

They played the scene, a little stiffly. Then Tucker caught his sleeve on a prop, and it fell onto the table. Meryl caught it before it broke. She placed it back up.

"And from that moment everything was just fine," she would recall, "because something real had happened, and it pulled us right onto the table, into the world. And then all the work we had done in rehearsal and the life we had lived and who we were, we just located ourselves in the tactile world and there we were."

The critics had other ideas.

"Mr. Antoon has transposed the play to New York at the turn of the century. Why?" Clive Barnes practically screamed in the Times the next morning. "What new resonances does he get from it? Is he trying to make it more relevant to American audiences or easier for American actors? Does this make it more meaningful? Or is it merely another example of the Shakespeare Festival determination to do almost anything just as long as that anything is different. This is a folly. And symptomatic folly at that."

"WATCHING THEM DEVELOP SOMETHING TOGETHER WAS ELECTRIC;

Walter Kerr piled on in the Sunday edition, under the headline "A Chorus Line Soars, Trelawny Falls Flat." "The lights are no sooner up on a theatrical roominghouse," he wrote, "than the good folk carrying the opening exposition are cackling like wild geese to assure us that something is, or is going to be, hilarious around here." However, he added: "In the overstressed onrush, only two figures emerge at all: Meryl Streep as a glossily successful former colleague who has gone on to "star' in another theater, tart, level-headed, stunningly decked out in salmon gown and white plumes; and Mary [B]eth Hurt, as Rose Trelawny herself, who is at the very least deeply satisfying to look at."

No doubt, the show was a turkey, at least with critics. The cast was stunned—the audiences seemed to be having a good time.

Meryl wasn't glum. Along with Kerr's peck on the cheek, the show had collateral benefits. Shortly before Thanksgiving, the screen legend Gene Kelly came and greeted the starstruck cast backstage. With him was Tony Randall, famous from The Odd Couple. Randall told the actors that he was planning to start a national acting company and he wanted the Trelawny cast to join. It sounded heavenly (though it wouldn't materialize until 1991). Still, the young cast didn't take him entirely seriously: Why wait for Tony Randall? They already felt like a repertory company. They had each other.

MERYL STREEP CAME TO NEW YORKwith a primary goal: not to get typecast. At Yale, she had played everyone from Major Barbara to an 80-year-old crone. In the real world, it wasn't so easy. "Forget about being a character actress. This is New York," people kept telling her. "They need an old lady, they'll get an old lady—you're going to get typed, get used to it." More than once, she was told she would make a wonderful Ophelia.

But she didn't want to play Ophelia. And she didn't want to be an ingenue. She wanted to be everything and everybody. If she could just hold on to that ability to carousel through identities—that repertory thing she had mastered at Yale and the O'Neill—she could be the kind of actress she wanted to be. Had she landed in a movie or a Broadway musical right out of school, she might have been pegged as a pretty blonde. Instead, she did something few svelte young actresses would do: she played a 230-pound Mississippi hussy.

The Phoenix Theatre company had been around since 1953, when it opened a play starring Jessica Tandy in a former Yiddish theater on Second Avenue. Since then, despite its shoestring existence, it had produced dozens of shows, from the Carol Burnett vehicle Once Upon a Mattress to The Seagull, starring Montgomery Clift. Its gentlemanly co-founder, T. Edward Hambleton (his friends called him "T" ), wasn't ideological like Papp. His guiding principle was: Produce good plays.

By 1976, the Phoenix was operating out of the Playhouse, a small Broadway theater on West 48th Street. Like other theater companies in town, it was planning an all-American season to celebrate the coming Bicentennial. First up: a double bill showcasing the twin titans of mid-century American play writing, Tennessee Williams and Arthur Miller. Both men were in their 60s, their reputations secure enough to render them slightly out of date. And yet the contrast would give the evening some frisson: Williams, the lyrical, sensuous Southerner; and Miller, the lucid, pragmatic Northerner.

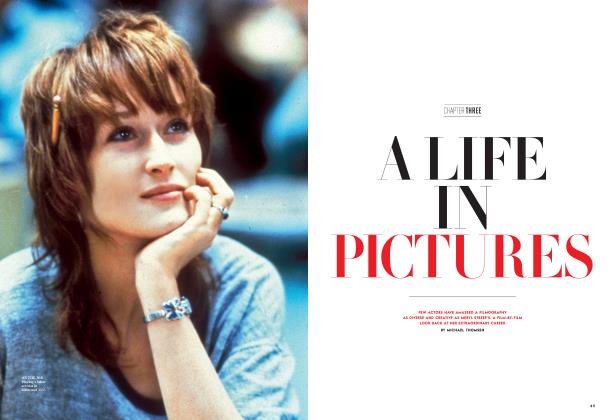

When Meryl saw the part she was reading for, she couldn't quite believe it. Set on a front porch in the Mississippi Delta, Williams's 27 Wagons Full of Cotton is a tour de force for whoever plays Flora, a raunchy Southern sexpot with a big cup size and a low IQ. Flora is married to the unsavory owner of a cotton gin who calls her "Baby Doll." When a rival cotton gin mysteriously bums down, the superintendent comes by asking questions. Flora suspects her husband (who of course is guilty as sin), and the superintendent traps her in a randy cat-and-mouse game, wangling information out of herwith coercion, threats, and sex. In Baby Doll, Elia Kazan's 1956 film adaptation, Carroll Baker had immortalized the role as a Lolita-like seductress, her sexuality practically bursting from her dressnothing like the 125-pound slip of a thing that called itself Meryl Streep.

Exhausted after an eight-hour Trelawny rehearsal, Meryl arrived at the audition in a plain skirt, a blouse, and slip-on shoes. Carrying a supply closet's worth of tissues she had swiped from the ladies' room, she introduced herself to Arvin Brown, the director. Sitting next to him was John Lithgow, who was directing another Phoenix show. In Drama, Lithgow recalled what happened next:

"As she made small talk with Arvin about the play and the character, she unpinned her hair, she changed her shoes, she pulled out the shirttails of her blouse, and she began casually stuffing Kleenex into her brassiere, doubling the size of her bust. Reading with an assistant stage manager, she began a scene from 27 Wagons Full of Cotton. You could barely detect the moment when she slipped out of her own character and into the character of Baby Doll, but the transformation was complete and breathtaking. She was funny, sexy, teasing, brainless, vulnerable, and sad, with all the colors shifting like mercury before our eyes."

Arvin Brown hired her immediately. But he must not have noticed the transformation that had occurred right in front of him, because when rehearsals began, he took a good look at his leading lady and panicked. Her magic trick had worked so well he hadn't realized it was all an illusion. " She was SO slim and blonde and beautiful, and somehow or another in the audition she had convinced me that she was this really slatternly, sluggish redneck," Brown recalled. He thought, Is this going to work?

Continued on page 86

Continued from page 17

Meryl was getting worried, too. Her fake D cup had been a way to trick not just the audition room but herself. Without the reams of paper stuffed in her brassiere, she was losing her grip on the character. "Let me try something," she told Brown.

She went out and returned with a slovenly old housedress and prosthetic breasts. She had found Baby Doll—and Brown once again saw a "zaftig cracker." Far from playing a femme fatale, Meryl tapped into Flora's innocence and vulgarity, which should have contradicted each other but didn't. Brown sensed a hint of rebellion: "I had the feeling she was kind of kicking the traces of a fairly conventional background."

Onstage at the Playhouse in January, 1976, Meryl's Baby Doll announced herself with a squeal in the dark:

"Jaaaaaake! I've lost m' white kid purse!"

Then she clomped into view in high heels and a loose-fitting dress, a buxom, babbling dingbat with a voice like a bubble bath. Between her lines, she cooed, cackled, swatted at imaginary flies. At one point, sitting on the porch with her legs splayed, she looked down at her armpit and wiped it with her hand. Moments later, she picked her nose and flicked away her findings. It was one of the funniest and most grotesque things Meryl had done. But her Flora was rooted in a goofy kind of humanity. The Village Voice called her: "a tall, wellupholstered, Rubenesque child-woman; a sexy Baby Snooks, tottering around on dingy creamcolored high-heeled shoes, giggling, chattering in her little-girl voice, alternately husky and shrill, mouthing her words as if too lazy to pronounce them properly (and yet you can understand every word), tonguing her lips, smiling wet smiles, playing with her long blonde hair, cuddling her boobs in her arms, lolling and luxuriating in her body as if it were a warm bath. And all this extravagant detail is as spontaneous and organic as it is abundant; nothing is excessive; nothing is distracting; everything is part of Baby Doll. What a performance! "

Even Tennesse Williams was impressed. In the lobby, Williams cornered Arvin Brown to tell him how much Meryl's performance had astounded him.

"It's never been played like that!" he kept saying.

DESPITE HER ADVANCEMENTS, she still didn't see herself as a movie star, and neither did the rest of the world. Or so it appeared one afternoon, as she sat across from Dino De Laurentiis, the Italian film producer whose credits included everything from Fellini's La Strada to Serpico. De Laurentiis was casting a remake of King Kong, and Meryl had come in to audition for the part made famous by Fay Wray—the girl who wins the heart of the big gorilla.

De Laurentiis eyed her up and down through thick square spectacles. From his office at the top of the Gulf and Western Building, on Columbus Circle, you could see all of Manhattan. He was in his 50s, with slickedback salt-and-pepper hair. His son, Federico, had seen Meryl in a play and brought her in. But whatever the younger De Laurentiis saw in her, the older certainly did not.

" Che hrutta/" the father said to the son, and continued in Italian: This is so ugly! Why do you bring me this?

Meryl was stunned. Little did he know she had studied Italian at Vassar.

"Mi dispiace molto, " she said back, to the producer's amazement. I'm very sorry that I'm not as beautiful as I should be. But this is what you get.

She was even more upset than she let on. Not only was he calling her ugly—he was assuming she was stupid, too. What actress, much less an American, and a blonde at that, could possibly understand a foreign language?

She got up to leave. This was everything she feared about the movie business: the obsession with looks, with sex. Sure, she was looking for a break, but she had promised herself she wouldn't do any junk. And this was junk.

When she learned that Jessica Lange had gotten the part, she didn't pout. She hadn't wanted it that badly, to tell the truth. She knew she wouldn't have been any good in it. Let someone else scream at a monkey on top of the Empire State Building. They wanted a "movie star," and she wasn't one.

She was too hrutta.

Theater was where her heart was.

One night at the dress rehearsal for Trelawny of the "Wells, " Joe Papp had told her, cryptically, "I may have something for you." Then, on Christmas Eve, 1975, the phone rang.

"How would you like to play Isabella in Measure for Measure in the park?" the producer said.

Meryl was... confused. Had he lost his critical faculties? She knew he had his favorites, and anyone let into Joe's inner circle was employed for life, like at a Japanese corporation. But Isabella? Wasn't that the lead?

"What I thought was great about him was that he treated me as a peer," she would recall. "Right from the beginning, when I was this unknown, completely ignorant drama student, way before I was ready for it, he admitted me to the discussion as an equal." The two of them had the same birthday, June 22, and they felt like they were cosmically linked.

"His conviction about me was total," she said, "but somewhere in the back of my brain I was screaming: 'Wow! Wow! Look at this! Wow!"'

By any actor's standards, her first season in New York had been charmed: back-to-back Broadway plays, a Tony nomination for 27 Wagons, and, coming up, a starring role in Shakespeare in the Park. Plus, one day in May, there was a phone call.

Them: "Would you like to fly to London?"

Meryl: "Sure." (Pause.) "What for?"

The answer was an audition for Julia, a film based on a chapter from Lillian Heilman's mem oi r Penlimento. The story (of questionable veracity) concerned the playwright's childhood friend, who was always more daring than she. Julia becomes an anti-Nazi activist, and enlists Lillian to smuggle money to Resistance operatives in Russia. Unlike King Kong, this was the kind of movie Meryl saw herself in: a tale of female friendship and daring—i.e., not junk. Jane Fonda was playing Lillian. The director, Fred Zinnemann, was thinking about casting an unknown for Julia.

For now, Meryl couldn't stop staring at the plane ticket to London: $620.

"When I was at Yale, people on partial assistance like me got $2.50 an hour when we were on stage," she told her lunch date one day at Cafe des Artistes, a Village Voice reporter named Terry Curtis Fox. It was her first professional interview. "Before this year the most money I ever made was waitressing. $620. And that's only for an audition. It's crazy."

Another thing: She didn't have a passport. She had never needed one.

TEN MINUTES BEFORE the first performance of Measure for Measure, a man in the audience had a heart attack. An ambulance rushed him to Roosevelt Hospital, but he was dead on arrival. At eight o'clock, the rain began, and the stage manager held the show for 20 minutes. They got through Act I before the downpour intensified. The performance was finally canceled, and everyone went home soaked.

Even in dry weather, the play was challenging. Neither tragedy nor comedy, Measure for Measure is one of Shakespeare's ambiguous "problem plays." The plot rests on a moral quandary: Vienna has become a den of brothels, syphilis, and sin. The Duke (played by the 35-year-old Sam Waterston) leaves his austere deputy, Angelo, to clean up the mess. To instill fear of the rule of law, Angelo condemns a young man named Claudio to death for fornication. Claudio's sister, Isabella, is entering a nunnery when she hears the news. She begs for mercy from Angelo, who is knocked senseless by lust. He comes back with an indecent proposal: Sleep with me and I'll spare your brother's life. Despite her brother's pleas, Isabella refuses, telling herself:

Then, Isabel, live chaste, and, brother, die:

More than our brother is our chastity.

The line usually draws gasps.

"The role is so beautiful, but there are so many problems in it," Meryl said at the time. "One is that it's so hard for a 1976 audience to sit back and believe that purity of the soul is all that matters to Isabella. That's really hard for them to buy." Sure, Angelo's a pig, most people think. But, come on, it's your brother's life! Just sleep with the guy!

Meryl was determined to find Isabella's truth, to make her dilemma real even if the audience was rooting against her—the same hurdle she would face in Kramer vs. Kramer. Could she get people to side with a fanatic nun? "Men have always rejected Isabella, right through its history," she said during rehearsals, with anticipatory relish. From his retirement in Connecticut, her father dug up all the reading material he could find on the play. "He's really quite a scholar," Meryl would brag.

A plum role for Meryl Streep was one reason Papp had booked Measure for Measure, but the timeliness of the plot was likely another. Shakespeare's Vienna is rife with corruption and perversity and grit, and the New Yorkers who had lived through the city's near bankruptcy could relate. Meanwhile, the whole country had gotten a lesson in official pardons, like the one Isabella seeks for Claudio. Two years earlier, President Gerald Ford had pardoned Richard Nixon for his Watergate crimes and now was paying a heavy toll in his electoral ran against Jimmy Carter. Everywhere you turned, someone in the halls of power was making a shady backroom deal, or a city was crumbling under the weight of its own filth.

The director, John Pasquin, envisioned a Vienna that would reflect New York back to New Yorkers. Santo Foquasto's set looked like a subway station, or like the men's room right outside the theater: all sickly white tiles, practically reeking of urine, against a skyline of painted demons. While Angelo and his officials sneered from a raised walkway, the bawds and whores of Vienna rose up from a trapdoor, as if ascending from the underworld. It was Park Avenue society meeting the drifters of Times Square, the bifurcated city Papp had tried to unite in his theaters.

Meryl read the long and churning play over and over again. Cloaked in a white habit, she had only her face and her voice to work with. And in the park, exposed to the elements, her meticulous characterization could get easily thrown off course. One night, during the climax of her big soliloquy—"I'll tell him yet of Angelo's request, / And fit his mind to death, for his soul's rest"—what sounded like a Concorde blasted overhead, and she had to scream "his soul's rest." "It's ludicrous," she said soon after, "but it costs me my heart's blood, because I carefully put together a person and a motive, and then something comes along that's not even in the book, and ruins it."

But something else was happening to Meryl Streep, something she had even less control over than jumbo jets roaring over Manhattan. It was there for everyone to see in her scenes with the 41-year-old actor playing Angelo, John Cazale, of The Godfather and Dog Day Afternoon fame. The push and pull of wills, the saint and the sinner locked in a battle of sex and death: It gave off heat. She stared into her leading man's coal-like eyes, his sallow face betraying awhimpering sadness. He gave her fire, she answered with icicles:

ANGELO

Plainly conceive, I love you.

ISABELLA

My brother did love Juliet,

And you tell me that he shall die for't.

ANGELO

He shall not, Isabel, if you give me love.

Meryl's understudy, Judith Fight, would watch the Isabella and Angelo scenes every night, memorizing the contours of Meryl's performance in case she ever had to go on. (She didn't.) "It was their dynamic that carried the production along, and watching the two of them develop something together was incredibly electric," Fight recalled. "You could see that something was developing, and that she was allowing herself to also be lifted by him."

Michael Feingold, Meryl's old friend from Yale, saw it, too. "The physical attraction between them was very real," he said. "And the idea of starting an Isabella-Angelo relationship with that present, not only in the actors' lines but in their lives... It puts an extra charge on everything, and she had that even inside the nun's habit."

Even the Times critic Mel Gussow picked up on it: "Miss Streep," he wrote, "who has frequently been cast as sturdier, more mature women, does not play Isabella for sweetness and innocence. There is a knowingness behind her apparent naivete. We sense the sexual give-and-take between her and Angelo, and she also makes us aware of the character's awakening feelings of self-importance and power."

If he only knew the half of it.

When Measure for Measure is about a nun putting her principles over her brother's life, it's a problem play. But this Measure for Measure was about a man and a woman battling their unquenched sexuality, making pronouncements and questioning them at the same time, their ideals betrayed by their irrepressible desire. It is Isabella's purity that lights Angelo aflame, as the whores of Vienna could not. The two actors were nearly as preposterous a couple as their characters: the ice princess and the oddball. And yet everyone, onstage and off, seemed to feel their spark.

On opening night, Meryl and her Angelo slipped away from the cast party. They wound up at the Empire Diner in Chelsea, a greasy spoon tricked out in Art Deco silver and black, with a miniature Empire State Building on its roof. They ate and talked, and by the time she got home it was five in the morning. She couldn't sleep.

She woke up the next morning to let a reporter up to her apartment. As they talked over orange juice and croissants, her eyes were bloodshot, her face devoid of makeup. Even as she fielded questions about her extraordinary first year out of drama school, her mind kept returning to John Cazale. There was something about this guy. Something.

She heard herself say, "I've been shot through with luck since I came to the city..."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now