Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowI've been an avid watcher of The Crown for its first two seasons. It is one of the most subtle and fascinating studies of female power I've seen.

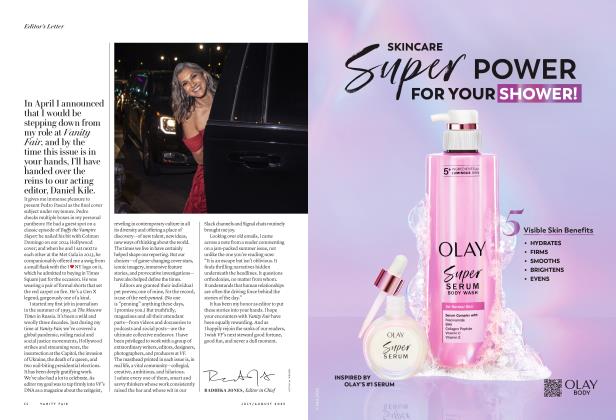

May 2018 Radhika JonesI've been an avid watcher of The Crown for its first two seasons. It is one of the most subtle and fascinating studies of female power I've seen.

May 2018 Radhika Jones

I've been an avid watcher of The Crown for its first two seasons. It is one of the most subtle and fascinating studies of female power I've seen. Like so many women in history, Elizabeth II learns to lead less by exercising direct authority than by mastering the covert art of influence. In part that's because the actions of the British monarch are carefully circumscribed, but it's also because no one expected her to ascend to the role so young and so untried. To see her hold her own against Churchill even in their fictionalized versions—is a cathartic experience. The show has also grappled with the intersection of monarchy, celebrity, and the press. In Season One—or as we call it in real life, the 1950s—television and mass-media coverage humanize the new Queen, literally bringing her closer to her subjects. But when those same forces begin to focus on her sister, Margaret, in love with a divorced man, the royal narrative is wrested back into the narrow lane of tradition, and the couple part.

When the engagement of Prince Harry and Meghan Markle was announced in November, I thought about that thwarted union of Margaret's. Six decades later, the same Queen who could not sanction her sister's wedding conferred her blessing on her grandson, as he sought to bring a divorced American actor into the family. Elizabeth turned 92 in April, and The Crown has helped to recast her reign—the longest of any British monarch in history—as groundbreaking and risk-taking, even as she also succumbs to protocol after stultifying protocol. If the Queen and her family have lagged, it has been in their unwillingness to reimagine the kind of people who might join their ranks. Exclusivity, not inclusivity, has been the watchword. The welcome of Kate Middleton and now of Meghan Markle suggests that they are catching up. And it matters, because the families of heads of states act as symbols. Their health and stability are a metaphor for the health and stability of the nation. Their values, for better and worse, have the power to reflect, and maybe even redirect, the nation's values.

With that in mind, we set about preparing to cover this busy, happy season in the House of Windsor—one in which we Americans claim an extra investment, given that one of our own citizens plays a starring role. I remember waking up before dawn on the morning of July 29,1981, to watch what was billed as the Wedding of the Century, uniting Prince Harry's parents. I don't recall having particularly princess-themed aspirations; I suspect the pageantry is what drew me in, and the undying allure of appointment television. It's fun to watch what the world is watching. But in considering what it might mean to an eight-year-old girl today to watch Meghan Markle—a self-made woman, bi-racial, the first in her family to graduate from college, with a passion for social justice, and who in the face of bigoted remarks about her background conducts herself with grace and authenticity— I'm struck by how powerful it can be to expand our notions of female ambition and achievement. Once upon a time, a girl like Meghan could grow up to be a princess. In the 21st century we might do better to think of it this way: a princess could grow up to be Meghan Markle.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now