Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowWhat it took to get my movie about Donald Trump and Roy Cohn in front of an audience

HOLLYWOOD 2024/2025 Gabriel ShermanWhat it took to get my movie about Donald Trump and Roy Cohn in front of an audience

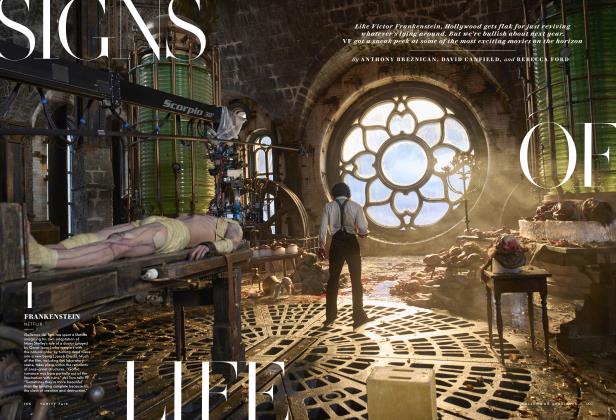

HOLLYWOOD 2024/2025 Gabriel ShermanON THE NIGHT of May 20, I stood in the storied Auditorium Louis Lumière at Cannes and listened as more than 2,000 people in black tie gave an eight-minute standing ovation for the film I wrote: The Apprentice. The movie is a Frankenstein's monster origin story about Donald Trump, played by Sebastian Stan in prosthetics and a golden toupee. It follows Trump as he rises in Manhattan real estate under the tutelage of lawyer turned fixer Roy Cohn, played with dead-eyed menace by Jeremy Strong. One scene depicts Trump sexually assaulting his first wife, Ivana. Others showed Trump getting liposuction, undergoing scalp reduction surgery, and popping amphetamine diet pills—details reported in Harry Hurt Ill's 1993 Trump biography, Lost Tycoon. (Trump denied the claims at the time.)

During the after-party, with views of oligarch-owned yachts anchored in the harbor, I began getting alerts on my phone: Trump announced he planned to sue to block the movie's release. Campaign spokesperson Steven Cheung called the movie "malicious defamation" and "election interference by Hollywood elites." I had a pit in my stomach, but I also felt strangely validated. Trump's legal threat followed the first rule Cohn elucidates in the movie: Attack, attack, attack.

Two days later, Trump's lawyers sent the film's director, Ali Abbasi, and me cease-and-desist letters that warned Hollywood companies against distributing the movie.

I hoped the controversy and buzz would translate into a deal. But by the time I flew home, no Hollywood company had made an offer to release the movie in the United States.

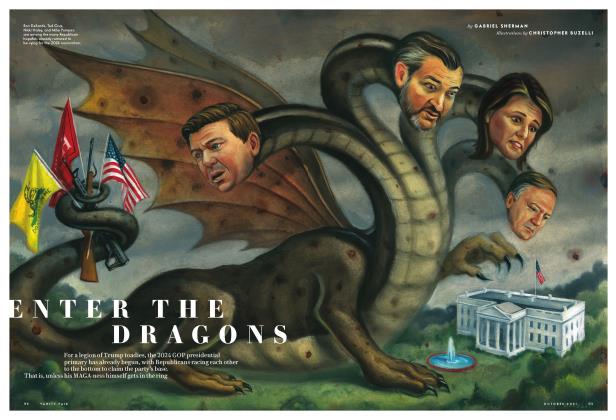

In the spring of 2017, millions of Americans were processing the reality that Trump occupied the White House. Some turned to therapy. Others booze. I coped by writing a screenplay. My first journalism job was reporting on Manhattan real estate for the weekly New York Observer. So you can imagine my shock when I found myself covering Trump's first presidential campaign. Roger Stone told me Trump was winning because he followed Cohn's three rules: Attack, attack, attack. Deny everything, admit nothing. And always claim victory. The insight sparked the idea to write a fictional film about Cohn molding his apprentice.

Their relationship had elements of a Shakespearean drama. Desperate to outshine his provincial father, Trump sold his soul to learn Cohn's dark arts. But Trump virtually abandoned Cohn while Cohn was dying from AIDS in the mid-1980s.

In the fall of 2017, my agent sold the pitch to Amy Baer, a former top studio executive who runs a small film-development company. Baer believed in the idea for the same reason I did: In our hyperpolarized culture, portraying Trump as human was a radical act. We then recruited Abbasi, an acclaimed Iranian Danish filmmaker.

NO MAJOR HOLLYWOOD studio or streamer wanted to finance the film. "Call me if Trump loses," one top executive said at a party after he told me how much he loved the script. But even then, studios still passed.

That meant we would have to finance the movie independently. Baer would raise most of the production budget by "preselling" rights to distribute the film abroad. An equity investor would provide the rest of the money, and we would show the movie at a major festival to entice a US distributor. Baer's ability to presell depended on casting stars with international fan bases to play Trump and Cohn. I wasn't prepared for actors, many of whom were #Resistance members, to be reluctant about the movie. One turned down the role of Trump saying he didn't want to give his "humanity" to the president.

Stan was the exception. Eventually we signed Emmy winner Jeremy Strong, who was looking for post-Succession roles, to play Cohn.

Even after we found our cast, the movie died and was resurrected many times. Trump's Muslim travel ban made it virtually impossible for Abbasi to work on the movie in the United States. Then there was a global pandemic, the bursting of the Hollywood content bubble, and dual writers and actors strikes.

In the spring of 2023, Abbasi was at Cannes promoting his Iranian serial killer film, Holy Spider, when he was contacted by a 29-year-old filmmaker and producer named Mark Rapaport. Rapaport told Abbasi to meet him on an unremarkable boat that ferried him to a 305-foot yacht. It belonged to Rapaport's father-in-law, the billionaire (and Trump donor) Dan Snyder, who had loaned Rapaport millions to help grow his production company, Kinematics.

Why did Snyder, who donated $1 million to Trump's 2016 inauguration, allow his money to go into an R-rated film that depicts Trump as a sex predator? The answer, as best as I can tell, is that Snyder didn't know what kind of Trump movie his son-in-law was making. (Lawyers who have represented Snyder in the past did not return a request for comment.) And why would my producers finance a dark Trump movie with money from a pro-Trump billionaire? As studios limit output, filmmakers seeking to finance adult dramas have had to look elsewhere. One enduring source of capital comes from the children (or spouses of the children) of the 0.1 percent. The problem, in our case, is that such people often have a Trump connection.

LIFE WAS IMITATING ART. Trump's legal threat followed the first rule Cohn elucidates in the movie: ATTACK, ATTACK, ATTACK.

We wrapped production in late January after a 32-day shoot. The plan was to premiere the movie at the Venice Film Festival in late August. But then our financier told Abbasi to get the movie ready to play at Cannes in May to quickly recoup. Snyder planned to host a party in Cannes on his yacht. Rapaport agreed to invest $450,000 more in the film.

In late March, Abbasi delivered his rough cut to producers. That's when I became aware of a war playing out between Abbasi and Rapaport. The biggest issue was the sexual assault scene, which dramatized allegations Ivana made in a deposition during her 1990 divorce. (Ivana later clarified that when she had used the word rape under oath, she didn't mean Trump assaulted her in a "criminal sense," only that she felt violated. She fully recanted her sworn testimony when Trump was running for president 25 years later.) Rapaport and his business partner told Abbasi the scene was too risky to portray.

Making matters worse, Rapaport screened the rough cut for his father-in-law at his Caribbean vacation home. Abbasi's draft included an improvised dream sequence in which Strong wore a skintight frog costume and climbed into bed with Stan and caressed his face. Snyder eventually walked out.

"I thought it was funny when I was on set...but this is not in the script," Rapaport told Abbasi and producers on a Zoom. Abbasi agreed the scene didn't work. But he and I refused to cut the sexual assault scene because we believed Ivana's sworn deposition. Trump has been credibly accused of sexual assault by many women over the years. He has denied all accusations.

On a certain level, I felt for Rapaport, stuck on an island with his billionaire father-in-law. He had financed the movie when no one else would.

IN THE WEEKS leading up to Cannes, Rapaport's lawyers sent producers cease-and-desist letters to stop the movie from playing the festival he had asked us to submit to in the first place. Rapaport only dropped his legal threats because the French distributor owned the movie in France. Still, there would be no yacht party.

In June, Briarcliff Entertainment made an offer to release The Apprentice in theaters before the election. The small company was founded by Tom Ortenberg, a veteran executive with a track record of distributing commercially successful political films.

But Rapaport wanted to hold out for a better deal, which seemed absurd because every other buyer had already passed. Rapaport was the movie's largest equity investor, which gave him power to approve domestic distribution. Would he really catch-and-kill his own movie? I told Strong that it was like we were living inside an episode of Succession.

It would be impossible to release the movie in the US before the election if the Briarcliff deal didn't close by Labor Day. I consoled myself that at least the film would be released in other countries in October—even in Vladimir Putin's Russia. That hope died when producers told me international distributors didn't have the legal right to screen the movie before it played domestically.

In the end, a pair of investors, Fred Benenson and James Shani, came together to buy out Rapaport's stake. The deal closed hours before the movie was scheduled to make its American premiere at the Telluride Film Festival. As our October general release neared, I braced for a lawsuit. "Talking about the movie puts him in a bad mood," a source close to the Trump campaign told me. In a social media post the weekend of release, Trump called the movie cheap and defamatory and maintained he and Ivana had a great relationship until her death. He also called me a "lowlife and talentless hack."

In a screenplay, a character's lowest moment is called the dark night of the soul. It's the final test that forces the protagonist to confront his worst fears and change. My dark night of the soul lasted four months as the movie lingered in purgatory. I'm a natural pessimist who assumes the worst will happen so I can be pleasantly surprised if anything goes right. My therapist asks me to accept forces I can't control and imagine a world in which things work out. Making this movie helped me to finally grasp these concepts.

Whether or not Trump files a lawsuit, Cohn's lessons worked in a way. The threat alone was enough to delay a deal for months. Cohn has been dead for nearly 40 years, but we're still living in his world.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now