Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

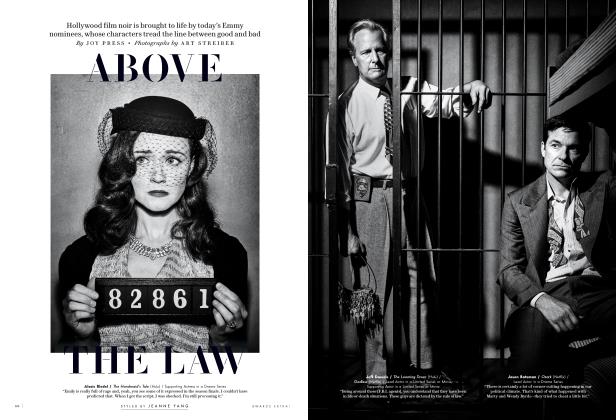

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowUnder John Landgraf’s leadership, FX has become a factory of prestige hits by not acting like a factory. Inside the mind of the streaming industry’s wise man and the studio that gave us The Bear, Shōgun, Fargo, and more

JUNE 2025 JOY PRESS ART STREIBERUnder John Landgraf’s leadership, FX has become a factory of prestige hits by not acting like a factory. Inside the mind of the streaming industry’s wise man and the studio that gave us The Bear, Shōgun, Fargo, and more

JUNE 2025 JOY PRESS ART STREIBERThe path to John Landgraf’s desk is a yellow brick road of prestige television. The walls of FX are lined with dramatic posters from the likes of The Americans, Fargo, American Horror Story, and Reservation Dogs. Inside the office lobby sits a piano with candy-colored keys, a prop from the eerie “Teddy Perkins” episode of Atlanta. Turn down any random hallway and you’ll likely run into a cache of golden statues. In 2024 alone, FX took home 36 Emmys. Thanks in large part to Shōgun and The Bear, it nearly topped Netflix and HBO’s combined tally.

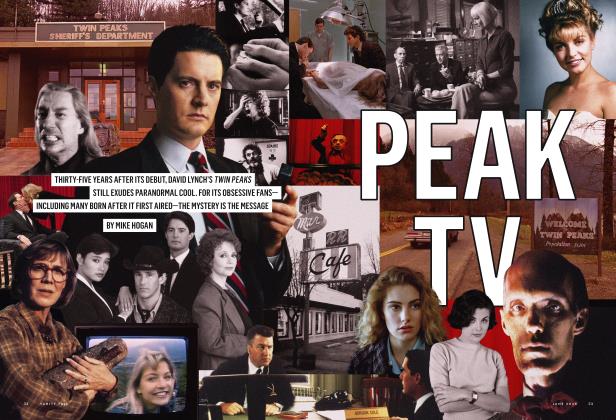

In the two decades he has been at FX’s creative helm, Landgraf has transformed it from a basic-cable network known for edgy, testosterone-soaked series like The Shield and Rescue Me into a singular brand that’s now the jewel in Disney’s crown. Landgraf doesn’t believe in churning anything out. Even in his years as chairman, he’s taken an artisanal approach to development. He steered FX through the collapse of the cable industry as well as the madness of Peak TV, a term he himself coined in 2015 to describe the glut of scripted series spewed out during the streaming wars.

ACCORDING TO THE GOSPEL OF LANDGRAF, MAKING GREAT WORK MEANS “CONTINUOUSLY LOSING YOUR WAY.”

Peak TV has peaked and most streamers are scrambling for safety, but FX keeps taking bigger risks—the latest being the upcoming Alien: Earth, inspired by Ridley Scott’s Alien franchise and created by Fargo showrunner Noah Hawley. Some showrunners worried that Disney, which bought what used to be called 20th Century Fox six years ago, might sandpaper down some of FX’s sharp edges. It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia, the longest-running live-action sitcom in American history, has been FX’s resident troublemaker since 2005. Its creator and star, Rob McElhenney, says that after the acquisition, Landgraf’s team assured him that nothing would change creatively. McElhenney and his Always Sunny friends tested the boundaries with a few offensive jokes anyway. “I thought, We’ll probably get a standards note on that. When we didn’t, we were disappointed. What do we gotta do to upset people?”

According to the gospel of Landgraf, making great work means “continuously losing your way. A television show is a living, breathing process that needs room for failure and also wild serendipity.” Collaborators gather his wisdom like Willy Wonka’s golden tickets. “I’m almost embarrassed to admit that today, in a meeting, I quoted John Landgraf,” says veteran producer Nina Jacobson, whose company Color Force is behind FX series such as Say Nothing and American Crime Story. “His approach to the business is so thoughtful that you often find yourself referring back to it, particularly in the heat of this algorithm-driven moment.” Brad Simpson, Jacobson’s producing partner, goes further: “He has a bit of a cult around him—people become obsessed.” Simpson sees Landgraf as “a studio executive therapist. He has that vibe of ‘I understand you…but you still have to make this show work for our audience and for a budget.’ ”

Pamela Adlon vividly remembers hanging out at a friend’s house when Landgraf called and asked her to sell him on why FX should greenlight her series Better Things. “I was like, Holy fuck, how do I do this?” But after an hour on the phone, she not only knew Landgraf’s obsessions and cadences but understood the mystique surrounding him. “He’s like a Buddhist monk that visits every country in the world and then likes to go on roller coasters with you. He’s a holy man, but he’s in the sandbox with you.”

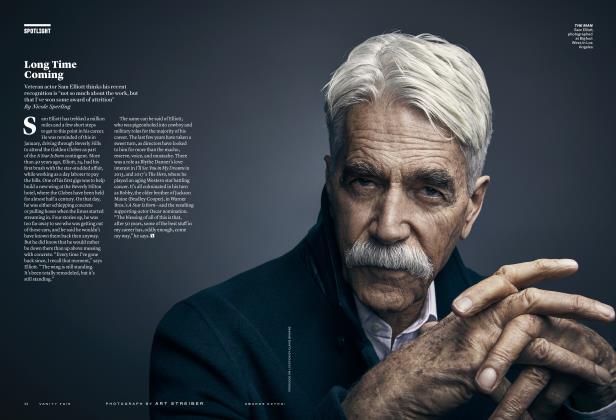

Sitting in a green velvet chair in his office on the Fox studio lot, Landgraf doesn’t look much like a holy man in his dapper blazer, close-cropped beard, and upscale combat boots. He does, however, use the words humble and humility a lot, as when he says, “I think humility is a superpower—being willing to acknowledge what you don’t know, to apologize and learn from things.” Over and over he points to his colleagues Gina Balian and Nick Grad, copresidents of FX Entertainment, as the originators of an idea or the cheerleaders for a particular project. In fact, when Balian was considering leaving HBO for FX in 2012, she was partly swayed by the way Landgraf so comfortably credited his colleagues for some of the network’s most successful shows.

“I could see that The Bear was excellent, but there were others, like Kate Lambert”—she’s a development executive—“that were absolutely relentless with me in saying, ‘This is the thing,’ ” Landgraf admits during the first of several long conversations. With both Atlanta and The Bear, he eventually came to a deep understanding of the shows and their creators, Donald Glover and Christopher Storer, respectively. “It took me a while,” he says, nodding soberly. “Neither one of them was particularly good at or interested in articulating what they were doing or why. They’re both very instinctive and have such distinctive visions that you have to [imagine] a whole other level on top of what you read on the page.”

In a joint email, Storer and executive producer Josh Senior say of Landgraf, “The questions he would then ask really make us do our homework. Why now? Why this restaurant? What are we saying overall? Can we take this tension further? Does it have to be that loud? When we ultimately arrive at an answer we’re excited about, I’m guessing it’s the one he’s already been at for a while.”

Resistant to the idea of television as interchangeable content, Landgraf aims to give shows time to find an audience and springs to his writers’ defense if necessary. He bristles when I mention some viewers’ disappointment in The Bear’s third season. “This is a show about codependency and stuckness and the kinds of substitute obsessions and addictions that people have,” he says vehemently. “I understand that watching someone not move forward is a lot less exhilarating than watching somebody make breakthrough after breakthrough, but if you’re not willing to let it rip, you don’t get The Bear. I just am madly in love with the season that we’re working on right now, watching Chris grapple with the question of: How does growth occur? How do epiphanies happen?”

A few weeks later I’m ushered through a barricade of production trucks on a quiet Chicago block that’s home to an old-school Italian sandwich joint. The sign hanging outside says “Mr. BEEF est. 1979,” but step inside and every corner is familiar as the original centerpiece of The Bear.

Instead of a line of customers, the counter is blocked by a rack of clothing, full of wardrobe choices for the cast of FX’s Emmy-winning series. Stars Ayo Edebiri and Jeremy Allen White stand in the corner of a concrete lot next door, laughing together. Minutes later they shoot a quietly emotional scene for season four. Each take feels slightly different, a symphony of small revelations. Storer (who also happens to be directing today) leaps up from the rickety box he’s been perched on and rubs his rumpled hair. “Hell, yeah!” he shouts, his highest accolade. “Moving on, guys!”

When the cameras aren’t rolling, Storer whirls around the lot, weaving gracefully through heavy equipment and crew members. A perfect combo of chill and exuberance, he constantly checks in with his cast. “Are you having fun?” Storer asks me at one point. “I mean, we have fun,” he says, nodding to the people scurrying around us, “but is it fun to watch?”

Ebon Moss-Bachrach, who plays Richie on the show, arrived early to observe his colleagues’ scenes. Remembering what it was like to film the first season during COVID, he says, “That’s part of why the show was so fun to make, and then so successful—the intimacy and proximity. I hadn’t been close to people in so long that it was nice to see people on top of each other.” Liza Colón-Zayas, who plays Tina, seconds this. Despite pandemic protocols, she says, “the chemistry from day one was enough.” Ricky Staffieri, who plays the comical Teddy Fak and is also a series coproducer, points to the mostly local Chicago crew and says, “The city gets behind us like crazy. On location, especially on days Jeremy’s there, it’s like the Beatles are coming.”

Storer and Senior say in their email about Landgraf and his team that they’ve learned over the course of the show that the most effective kitchens operate on trust. “John surrounds himself with people that he trusts,” they write, adding that the executives’ fingerprints are on every shot. “I think we take 99 percent of their notes/ideas? And vice versa. We’re on such a rushed production schedule, we can’t have any weirdness between us. The show would never make it on time.”

One of Landgraf’s favorite refrains is “It’s your vision, not mine.” According to Storer and Senior, “Any ideas or questions from John follow that philosophy; there’s always a push toward the vision. He doesn’t encourage us to take swings, he expects us to, which makes any sort of development process that much more clear because it protects the show from an easy or lazy solve.”

Landgraf describes his childhood as disjointed and solitary. His parents were itinerant evangelical musicians who both decided to get graduate degrees—and later a divorce. That made for a lot of moving around, which he believes fed his understanding of artists. “I really lived in a world of books and imagination and movies and television, and I always gravitated towards the artists and the nerds in school,” he says. “I found my people, and those are the same people that write television shows, act, and direct.”

Joel Fields, executive producer of FX’s The Americans, The Patient, and Fosse/Verdon, met Landgraf when Landgraf gave him a prospective student tour at Pitzer College. When I prod Fields for wild-oats-sowing tales—keg parties, bacchanalian nights—he shakes his head sadly. “If you want the dirt…he played the flute. Does that tell you what you need to know?”

After studying anthropology, Landgraf did a fellowship in political science and pursued a master’s in public policy. He never imagined himself working in the entertainment industry, but an internship shifted his career path. Six years at a production company led to a big leap: a gig as the vice president of NBC prime-time series during the network’s Must-See TV golden years, overseeing classics like The West Wing, Friends, and ER. A stint at Jersey Films followed, but Landgraf was increasingly convinced that the television business was broken.

“I didn’t feel I could protect the creative,” he says. “Writers have something they want to say, and I felt that in the commercial process—the sausage factory—most of that gets jettisoned in favor of: We need it to be paced like this and we don’t want to offend this person, and whatever other compromises you make along the way.” And the thing that gets lost? “It’s actually the animating spirit that makes great movies and great television.”

In 2003 Landgraf got a call asking if he’d be interested in working at a basic-cable network called FX. Launched by Rupert Murdoch’s News Corp., it had been a dowdy home for reruns until 2000, when an HBO marketing exec named Peter Liguori joined forces with Kevin Reilly, who’d helped bring The Sopranos into the world. Together they reconceived FX as a “free HBO” and proved their daring with two original series: The Shield, a raw ride-along with corrupt LA cops, and the plastic surgery dramedy Nip/Tuck. The Shield became the highest-rated basic-cable debut of its time; its star, Michael Chiklis, beat out West Wing’s Martin Sheen and Six Feet Under’s Michael C. Hall for the best-actor Emmy that first year. Nip/Tuck further whipped up excitement for the fledgling FX slate, introducing the wider world to a showrunner named Ryan Murphy.

Landgraf initially turned the FX job down. “I didn’t believe that I would find the creative freedom and ability to nurture talent at a basic-cable network inside Fox,” he says. Liguori finally convinced him, and Landgraf got to work shaping shows already in the works (Rescue Me, with Denis Leary) and developing new ones like It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia and Over There. The latter was a Gulf War drama, airing in the middle of the Gulf War. It flopped. “I think maybe on some unconscious level, I was trying to see if I would just get fired or shut down,” he says now with a hint of a smile. “Even though that didn’t work, it set the right tone, which is to say: Just try stuff, take shots.”

Murphy sometimes tested Landgraf’s convictions. During their early years working together, their clashes were “brutal,” Murphy once told Vanity Fair, to the point that he and Landgraf briefly stopped speaking to each other. But once they found an equilibrium, Murphy’s perverse creations (including AHS, Pose, Feud, and Grotesquerie) became a core element of FX’s DNA. Landgraf’s longtime Fox colleague and now Disney boss, Dana Walden, says that if you know both men—with their similar taste in books and their fascination with storytelling—their bond makes sense. “John has created for Ryan a playground where he can pretty much do anything he wants to do,” Walden says. “There’s really nothing Ryan comes up with that John ever has to say to him, ‘That’s not an FX show.’ John has done a really good job of maintaining extraordinary elasticity.”

Not that there’s no creative conflict. Murphy once told GQ, “He doesn’t yell, but he can annihilate you with his intellect and make you feel like a really shitty, bad person,” noting that Landgraf doesn’t do so to pick a fight: “He’s trying to change your behavior in the future.” When I read the quote to Landgraf, he replies with some amusement, “Look, Ryan does not love getting feedback or notes from anybody. In truth, he’s a visionary, and he does his own thing.” Murphy’s also a perpetual motion machine: He currently has multiple FX projects in development or production, including The Beauty, a new drama starring Evan Peters, and an American Love Story limited series about Carolyn Bessette and JFK Jr. “I know of three or four other things that he’s noodling and working on in his own way,” says FX’s Balian. “It’s almost like a brand within a brand—and a brand that’s been incredibly successful for us.”

Landgraf has a reputation as the head number cruncher of Peak TV. “John loves data,” says Warren Littlefield, executive producer of Fargo and The Old Man (and once upon a time, Landgraf’s boss at NBC). Landgraf often shares with producers what the numbers mean for FX, Littlefield continues: “I get a strong sense that at Disney, there’s buy-in to what John and his team are capable of doing.” Walden suggests Landgraf does indeed have buy-in. “We’ve been working together for a very long time, and there was a period where I was running the Fox television studio and John was relatively newly running FX, when we had very heated disputes over the business model and who should bear responsibility for which parts of the budget,” she recalls. “I think the strength of our relationship now is partly because we had that conflict, and we worked it out.”

The first wave of prestige television was a rogues’ gallery of alpha dudes. Even though Sex and the City was one of HBO’s first breakout hits, Tony Soprano set the mood: It was gonna be dicks all the way down. FX fit in perfectly, thanks to shows like The Shield and Rescue Me. That changed slightly when, according to Landgraf, a tight budget forced him to choose between two series they’d been developing. One was another male-antihero-driven drama, the other a legal thriller with a female protagonist. Landgraf hoped to broaden FX’s appeal to a female audience, which is how Breaking Bad ended up at AMC and Damages (starring Glenn Close) got Landgraf’s thumbs-up. Still, the cable network remained fairly white male–flavored in ensuing years, as Sons of Anarchy, Justified, and Louie kept FX’s flag flying.

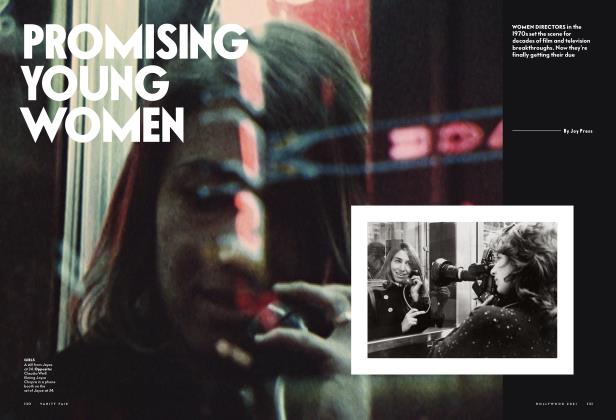

In the wake of Louie’s success, Landgraf says, “it occurred to us that white men had gotten the opportunity to do this sort of very personal show” while other creators (and audiences) remained neglected. FX began seeking out different perspectives. The scripts for Adlon’s Better Things and Glover’s Atlanta came in on the same day and premiered on the same week in September 2016, with FX’s first female and Black creator-stars.

Over a sushi lunch in the FX office, I ask Landgraf, Balian, and Grad why it took so long to greenlight a show created by a woman. “It’s not for lack of trying,” says Balian. “It was certainly a perception I had when I got here that FX did really well with male audiences,” which she suggests might have become a self-fulfilling syndrome. In recent years, a number of its limited series created by and starring women have aired, including Fleishman Is in Trouble, Mrs. America, and this spring’s searing Michelle Williams dramedy, Dying for Sex, from New Girl vets Elizabeth Meriwether and Kim Rosenstock. Taffy Brodesser-Akner, who adapted her novel Fleishman Is in Trouble for the FX limited series, remembers Landgraf spending a whole evening proposing a way to fix the pilot. “When I disagreed, he yielded to me,” she says. “And I thought, Wow, you are so insistent on your identity as a creator-first company that you actually do it.” She also confirms that Landgraf’s intellect is no joke: “He’ll bring Euripides into a conversation and assume you know what he’s talking about!”

“IN TELEVISION, BIG BETS ARE NOT A LOT OF FUN. YOU REALLY, REALLY SWEAT.”

FX wasn’t exempt from the #MeToo searchlight. Ironically, FX’s most high-profile female-driven series got caught in it. Louis C.K. had cocreated Better Things, and his public cancellation for sexual misconduct in 2017 left both Adlon and FX reeling. Landgraf looks grief-stricken when I mention his name. “It was devastating,” he says, pointing out that FX made four different series with C.K. and had no issues with him. FX Productions quickly canceled its overall deal with his production company, and Landgraf took pains to publicly attest that Adlon was Better Things’ creative engine. He also told Adlon to take the time she needed before returning to make a third season on her own. “I didn’t understand how to rebuild and come back from that, and he was just so patient with me, it’s gonna make me cry,” Adlon says now, her voice wavering. “I definitely think that the show got hurt by it, but it stayed alive.”

More recently, Brian Jordan Alvarez of FX’s comedy English Teacher was accused of sexually assaulting actor Jon Ebeling on the set of his 2016 web series The Gay and Wondrous Life of Caleb Gallo. FX has renewed English Teacher for a second season, and Landgraf chooses not to comment about that decision or about the allegations, which long preceded his company’s relationship with Alvarez. “I don’t want to litigate the English Teacher in a public way,” he says. “I can just tell you that we’ve gotten so much overwhelmingly positive feedback about the feeling people have of that show’s willingness to wade into contentious ground in ways that aren’t shrill, that make fun of dogmatism and arrogance.” Before the assault accusation came to light—Alvarez has insisted that everything that transpired was “entirely consensual”—many critics included the series in their best of 2024 lists alongside Shōgun.

The FX team seems to thrive when they’re creatively or financially out on a limb—whether it’s taking a gamble on an inexperienced artist or squeezing their budget to keep futzing with a project they love. “A lot of our biggest successes were pilots that we reshot all or most of,” Landgraf says, pointing to Sons of Anarchy and Snowfall. Balian embarked on creating Shōgun when she first arrived at FX; it went through two showrunners and 11 years of labor before it became a smash hit. The project also survived Disney’s acquisition of FX’s then parent company, 21st Century Fox. In many ways, the transition to Disney made it a reality. Says Landgraf, “Shōgun’s a huge swing, and a swing that we just never could have made as a basic-cable network, because it needs the potential of a global audience to make the investment reasonable.”

Landgraf had watched with fascination as the industry frantically tried to replicate the success of Game of Thrones. Creating an American historical epic seemed difficult in the recent political climate. “Every war we’ve ever fought is now politically contentious,” Landgraf points out—but 16th-century Japan isn’t. “I had conversations with my bosses saying, ’I think we have a way of making it 70 percent in English and 30 percent in Japanese,’ ” he says with a sheepish grin. When his team decided they preferred Japanese-speaking actors, Landgraf walked back his 70 percent promise but agreed to compensate by hiring a big star for the one British character. Soon, he walked even that back. One key to FX’s survival has been scrappiness and keeping a tight rein on finances. “In television, big bets are not a lot of fun. You really, really sweat,” Landgraf says. “And this was a 10-hour saga, more in Japanese than English. I doubt I’d be sitting here talking to you if it hadn’t worked.” Walden, his boss, shrugs off the notion: “He’s a very good storyteller.”

Justin Marks, who cocreated the Shōgun series with his wife, Rachel Kondo, remembers the first time he walked onto the massive soundstage to launch the show and realized there was no turning back. “That night, I went for a walk and sat on a bench in the park outside our building and just stared, like, How are we gonna survive this?” When I catch up with Marks and Kondo, they’re in the throes of writing the show’s second season and keenly aware of what it would mean if that season is underwhelming. “I liked it better when I didn’t know any of that,” he quips. “I think there are expectations, and there are ways that we’re going to surprise and exceed—and exceeding probably will cost a little more.”

Landgraf first proposed FX’s next pricey gambit, Alien: Earth, in 2018, while Disney’s acquisition of Fox was still in progress. Since then, FX has gained a strong foothold in the global streaming world, airing on Hulu in the US and on Disney’s international streaming service, Star. But Noah Hawley still feels the burden on him as he does postproduction on the Alien series: “You’re talking about a price point that’s at the top end of anything they’ve ever spent before.”

When Landgraf tells me some off-the-record details about the series, he’s as giddy with excitement as I’ve seen him. “The challenge of Alien is that most of the characters die at the end, it has one of the greatest cinema monsters, and one of the greatest production designs of all time,” he says. “If you’re spending that kind of money and working with intellectual property owned by and controlled by the corporation, you have to be thoughtful about it. I really appreciate that Noah has stayed true to himself and his originality. But it’s been grueling—and if I think it’s been grueling, it’s been five times as grueling for him.”

When asked what counts as success in FX’s Disneyfied streaming era, Landgraf throws out a mix of metrics: hours of consumption, good reviews, number of new subscribers a show brings in. But for him, one of the most important things is co-viewing: two or more people watching a show together in the same room. This is, he points out, “distinctly the opposite of how the internet works.” The message is that television is better when experienced communally. “We’re in a world of algorithms, and streamers are constantly looking for the hack to the system,” Grad tells me at one point. “There’s no cheat code.”

Okay, fine, but the brand’s sophisticated marketing has always helped enormously. “I can pick out an FX billboard anywhere,” says Mrs. America creator Dahvi Waller. “They understand what each show is, and they’re so creative about how they market it.” It’s not unusual for shows to sit neglected on streamers without target audiences even knowing that they exist. Says Waller, “That is definitely disconcerting, and it’s a big draw of FX.” Littlefield sometimes wonders if marketing boss Stephanie Gibbons understands his shows better than he does. “What they’re able to do in a world of infinite choice is break through the clutter so the show can have value and meaning to people.”

During one of our conversations, Landgraf leaps up from a chair in his office and grabs the laptop off his desk. He wants to show me an email he just got from a producer of FX’s A Murder at the End of the World. One of the thriller’s central characters is a former hacker and wife of a tech billionaire who dreams of escaping his underground bunker but doesn’t want to leave behind their young son. Landgraf points to an image on his screen, which is very much a real-life analogue to the show: It’s Elon Musk and one of his children romping in the White House, juxtaposed with a photo of the boy’s mother, Grimes, looking bereft.

“How do artists do that?” he asks. “Yes, it’s just pure coincidence on some level. But so often in my experience with artists, they just have an intuition about something that presages real life.” This is one of Landgraf’s favorite topics—the mysterious process of inspiration. “The world is a cacophony of sound,” he says. “But these people that we work with, they hear things, they feel things, they see things that I can’t. I just really admire that, to be honest with you. And I think I am pretty good at helping someone tune their receiver.”

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now