Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowA PHOTOGRAPHIC ANALYSIS OF GOLF

And the Lessons Learned from a Series of Novel Cyclograph Pictures

WALTER CAMP

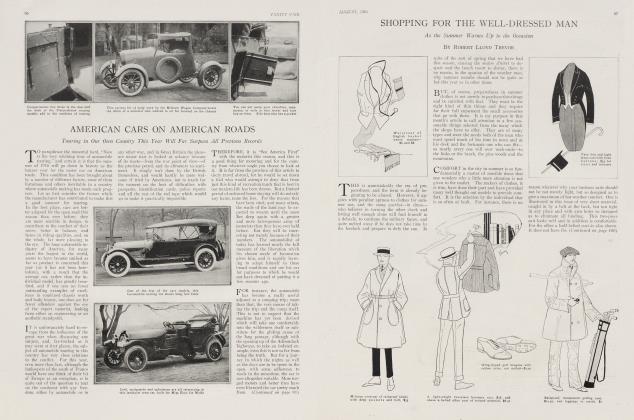

IN the days of his professorship at Yale, Professor Sumner used frequently to say that he would pursue Truth wherever it might lead him. When an undergraduate came to him, fired with youthful enthusiasm over some idea or other that would certainly upset the world, the professor had an irritating way of asking him three questions: "What is it?" "How do you know it?" "What if it is?"

A little over a year ago I met Frank B. Gilbreth, the consulting engineer. Mr. Gilbreth is an investigator of the Sumner, truth-pursuing type. In his merciless pursuit of it he has called in the aid of a novel form of flashlight negatives, which he calls cyclograph pictures. As a result of that fact I am able here to present a series of photographs taken by him, which are the result of weeks and weeks of practice and experiment; of the cooperation of five men skilled in golf, electricity and photography.

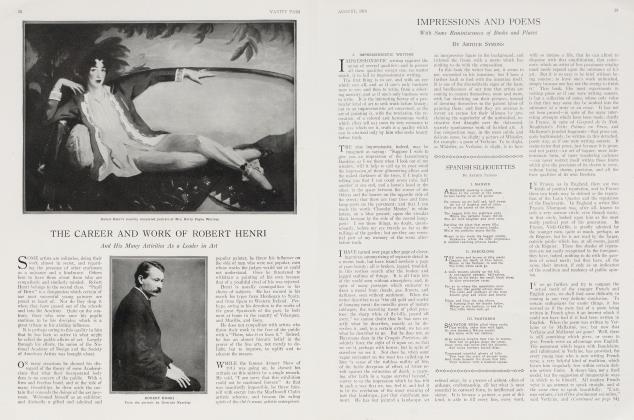

The larger photographs shown on these two pages are of Gilbert Nicholls, the gifted professional of the Great Neck Country Club, and a man whose form in golf is admittedly of the best.

IN the past few years I have been endeavoring to discover some means by which I could give to the thousands of youths and boys on the playgrounds of America a course of modern coaching in athletics by means of photographs. I finally discovered that Mr. Gilbreth had more or less solved the problems involved in such instruction as this by his experiments in factory work, and that he, like Professor Sumner, had had but one object in life, and that was to pursue the Truth wherever it might lead him. Mr. Gilbreth and I became enthusiastic over the possibility of extending his factory efficiency photographs into the realm of athletics, and we decided to choose golf as our first experimental stamping-ground. In his factory practice his object had been, of course, to show a workman, by means of flashlight pictures, how to perform a greater number of operations with his hands and arms, and to perform them more speedily and with greater dexterity than he had performed them before; but when the more rapid and rhythmic motions of a golfer like Gil Nicholls had to be dealt with, the problem became that of chaining and controlling, as it were, a veritable whirlwind in a laboratory.

WE finally devised a plan of posing Mr. Nicholls before a ruled blackboard; of placing a time clock beside him, of adjusting a light a little above the head of his golf club; of placing another light on his forehead and another on his right hand. These lights, after being attached, were made to flash in a series of intermittent sparks, generated on a cyclograph machine. It may be well to explain that, for the full drive and the full shots with a midiron and mashie (that is to say, for the three pictures shown on this page) this light flashed sixty times to the second; and that for the three-quarter and half mashie shots (that is to say, for the three large pictures shown on this page, (63) the light flashed fifty times to the second.

NO. 1. A full wooden shot, with the driver, posed by Gil Nicholls. In this negative no lights were used except one—and that was attached a trifle above the head of the club. This is a singularly interesting negative in that the entire course pursued by the club-head: is accurately reproduced in it. It will be seen from a study of this picture that the arc described by the club-head on the up swing is not exactly like that followed by it on the down swing For generations professionals have taught us that the swing of the club in coming down should be exactly the same as the swing of it in .going up, but we see here, in Gil Nicholls—as good a model of golfing form as one could find anywhere—that the two arcs are dissimilar and that the down swing is considerably closer to the body than the up swing.

NO. 2. A full midiron shot, by Gil Nicholls. In this negative a light was used on the club, a light on the right hand, and a light on the player's forehead. The swing up and the swing down are fairly, well shown, but the light was turned off on the head of the club after the contact of the club with the ball. It will be noted in this picture, just as it is'in No. 1, that the arc described by the descent of the club is not exactly the same as that described by the ascent of it.

NO. 3. A full mashie shot, by Gil Nicholls. Here an attempt was made to register the upward and downward swing employed in a. full mashie shot. No light was used except that on the club-head, the light being turned off after the contact of the club and ball. An indication is given of the wide variation between the position of the player's head in starting the swing and when finishing it, as two separate images of the player's head are faintly visible on the background of this negative.

NOS. 4 AND 5. Three-quarter mashie shots, by Gil Nicholls. In the previous picture (No. 3) the loop of a full mashie shot has been shown. In these two pictures (Nos. 4 and 5) a three-quarter mashie shot is shown. In No. 3, the full shot, the loop naturally extended further back over the player's head than in these two pictures of the player's three-quarter shots. In these two negatives lights were employed on the club-head, on the right hand, and on the forehead, the light being turned off at the contact of the club-head with the ball. The really interesting thing about these two nega-

tives, however, is the fact that the interval between their exposures was nearly half an hour. This can be proved by the record numbers on the negatives shown at the left of the pictures. As will be seen from a close study of the pictures, Gil Nicholls has, with almost absolute fidelity, repeated in the second negative the exact movements which he made in the first. In other words, a good golf player doesn't vary a half inch in duplicating one of his "stock" shots. The two pictures could be laid over each other without detecting any difference in them whatever.

NO. 6. A half mashie shot, by Gil Nicholls. In this picture lights were used on the club-head, on the right hand, and on the forehead, the light on the club being extinguished upon the contact of the club-head with the ball, but the right hand light and forehead light were continued to the end of the swing. It will be seen that in this picture of a half mashie shot the swing back and the follow through is only a little less pronounced than in the three-quarter shot .with the same club.

In this way it was found possible by the aid of a magnifying glass, to gather, with a fair degree of exactitude, the time required by Nicholls to make any given stroke, both in the upward swing and in the downward swing, by counting the breaks in. the flashing light which marked the course of the club-head.

On this page will be found two smaller pictures. The originals of these were posed by Mr. Roger Hovey, the distinguished amateur state champion of Rhode Island.

We found that in most of the Hovey trials—only two of which are used in this article—we could count the flashes quite easily, and our method of counting showed us that the down swing was accomplished, in each case, in just about half the length of time that it took to accomplish the up. swing. The same proportion of time was noted by us after a careful study of all the Gil Nicholls' pictures—twenty or more in number.

MY hope is that this is only the beginning of a long series ot experiments in the art of combining photography with athletic coaching. Indeed, the vista opened by the pictures here published is almost illimitable. It ought not to be long before we shall be able to see, in moving, cyclograph pictures, the best exponent of any department of athletics at his chosen sport, and, bv the aid of such pictures, to study his methods and discover how to achieve his results.

A combination of scientific measuring, accurate timing, and the proper sort of picture machine, ought to make it possible to reproduce at will the motions of an athlete, in any given sport, over and over again, as slowly or as rapidly as desired, before the eyes of any number oTwould-be athletes who may aspire to copy the model before them.

The whole art of picture photography is really in its infancy, and I look forward to the time when, not only motions purely automatic in character, such as are involved in the work of our ordinary American factories, but more rhythmic athletic motions as well, will be subjected to the tell-tale and truth-pursuing influences of the camera.

In golf, perhaps more than in any other sport, it will be possible to use such methods of photography as I have indicated for the improvement of students at large, for there is no game in which a correct form means so much as it does in golf.

It is a fact, I believe, that no golfer has ever reached a real high position in the world of golf—and held it—whose golfing form was not above reproach.

NO. 8. A full driver shot, by Roger Hovey. In this picture the photographic operator was standing at Mr. Hovey's side while Mr. Gilbreth is shown on the right of the picture, standing by a table and operating his cyclograph machine. Lights were employed on the club-head, on the right hand, on the forehead and on the left shoulder. It is interesting to note the loops made by Mr. Hovey's driver when viewed from a side angle, and not from the front view, as was done in picture No. 7.

NO. 7. A full drive, by Roger Hovey. This picture was posed with lights on the head of the club, the player's' right hand, his forehead, and his left shoulder. Note that the downward stroke doesn't follow the upward stroke. It is interesting to note the motion of the left shoulder which can ,be clearly traced, as well as that of the right hand. The light was flashing twenty times a second, and, as can be seen with the help of a glass, it took approximately twelve flashes on the up swing of the club and only six on the down.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now