Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowBULL-FIGHTING IN SPAIN

The Irresistible Attraction of las Corridas de Toros

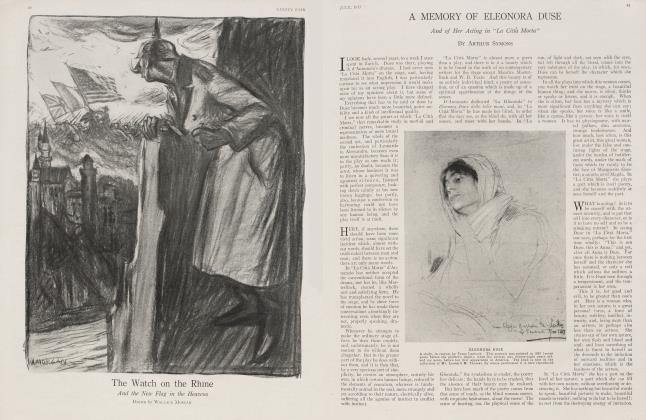

ARTHUR SYMONS

I HAVE always held that cruelty has a deep root in human nature, and is not that exceptional thing which, for the most part, we are pleased to suppose it. I believe it has an unadmitted abominable attraction for almost every one; for many of us, under scrupulous disguises; and a good deal more simply for others. The problem is troubling me at the moment, for I was at a Spanish bull-fight yesterday, the first I had ever seen; and I saw many things there of a nature to make one reflect a little on first principles.

THE Plaza de Toros at Valencia is the largest in Spain. It holds 17,000 people, nearly 3,000 more than those of Barcelona, Seville and Madrid. Yesterday it was two-thirds full, and, looking from the highest point of the house, I saw an immense blue circle filling the space between the brown sand of the arena and the pale blue sky overhead. The "Sol," the side of the sun, the cheaper side, was opposite to me, and the shimmer of blue came from the "gradas," where the blue blouses of the workmen left the darker clothes of their neighbors and the occasional colored dress of a woman hardly distinguishable as more than a slight variation in a single tone of color. Below me was the President's box, and half way round to the right, the band, which, punctually at three, began to play a march. Then a door in the arena, immediately opposite to me, was thrown open, and the procession came in, the 'espadas and banderilleros in their pink and gold, with their bright cloaks, walking, the picadores, pike in hand, on their horses, the chulos following. There were to be eight bulls, four in "plaza partida," that is, with a barrier dividing the arena into two halves, and four in "lidia ordinaria," with the whole of the arena. As soon as the men were in their places a trumpet was blown, two doors in the arena were thrown open, and two bulls, each with a rosette on his neck, galloped in. The two fights went on simultaneously, in the traditional three acts— the "Suerte de Picar," when the picadores, on horseback and holding long wooden pikes with a short head,—there is a famous painting of one of them, by Zuloaga—meet the bull; the "Suerte de Banderillera," when the banderilleros plant their colored darts in his neck; and the "Suerte de Matar," when the espada, with his sword and his red cloth, gives the death blow. Each fight lasted about half an hour, and was divided into its three acts by the sound of trumpets.

THE first act might be called the Massacre of the Horses. There is no pretense of fighting, and the picador rarely attempts to save his horse, although nothing would be easier; on the contrary, the horse is deliberately offered to the bull, with the very considerable chance, of course, that the picador himself may be wounded through his pads, or as he rolls over with his horse. The horses are old and lean, one eye is often bandaged, and if, as they often do, they press back in terror, against the barrier, or become unmanageable, a red-coated chulo comes forward and takes the bridle, and another follows with a stick, and the horse is led up to the bull and placed sideways to receive the charge. The bull, who has not the slightest desire to attack the horse, is finally teased into irritation by the red coats and by the pink cloaks, which are tossed and flaunted before him; he paws the ground, puts down his head and charges.

Continued on page 100

Continued from page 66

The pike pricks him, and his horns plunge into the horse's belly, or are caught on the loose wooden saddle, or, as happened once yesterday, scrape the picador's leg. The cloaks are flourished again, and the bull follows them. Then the horse, if he is still on his feet, is again turned to the bull. There is a great red hole in him, and the blood drips; but he is dragged and beaten forward. The bull plunges at him a second time, and this time he rolls over with his rider, who scrambles out from under him, his yellow clothes stained with red. Then one chulo takes the bridle and beats the horse on the head, and another chulo drags him by the tail, and, if he can, he staggers to his feet. He is literally falling to pieces, he has not ten minutes to live; but the saddle is thrown on him again and the picador helped into the saddle. He makes a few steps, the picador drives his heels into him, and then jumps off as he falls for the last time and lies kicking on the ground, a tom and battered and sopping mass. Then a chulo goes up to him, hits him on the head'to see if he can be made to get up again, and finding it useless, takes out a long, gimlet-like dagger, and drives it in behind his ear. Meanwhile another horse is being butchered, and the bull's horns have turned crimson, and his neck, where the pike htis struck into him, begins to redden in a thin line down each side.

THE trumpet sounds again, and if one of the horses is still living he is led back to the stables, to be used a second time. Now comes what is really skill in the performance, the planting of the banderilleras. The bull has tasted blood, he is still untired, and but slightly wounded. Little shouts of delight went through the house, and I could not but join in the applause, as Velasco nodded to the bull and waved the banderilleras close to his eyes, between his very horns, and planted them full-face, before he leapt sideways. And Velasco's play with the cloak! The whole house rose to its feet, in fear and admiration, once, as he wiped the ground with his cloak, only its own length from the bull, again and again and again, and then, wrapping it suddenly about him with its white side outwards, turned his back on the bull, and stood still.

THE trumpet sounds again, and the espada takes his sword and his muleta, and goes out for the last scene. This, which ought to be, is not always the real climax. The bull is often by this time tired, has had enough of the sport, leaps at the barrier, trying to get out. He is tired of running after red rags, and he brushes them aside contemptuously; he can scarcely be got to show animation enough to be decently killed. But one bull that I saw yesterday was splendidly savage, and fought almost to the last, running about the arena with the sword between his shoulders, and that great red line broadening down each side of his neck on the black: like a deep layer of red paint, one tricks oneself into thinking. He carried two swords in his neck, and still fought: when at last he, too, got weary, and he went and knelt down before the door by which he had entered, and would fight no more. But they went up to him from outside the barrier, and drew the swords out of him; and he got to his feet again, and stood to be killed.

As the espada bows and renders up his sword, the doors of the arena are thrown open, and there is a sound of bells. Teams of mules, decked with red and yellow bows and rosettes all over their heads and their collars, are driven in, a rope is fastened to the heads of the dead horses and the horns of the dead bulls, and they are dragged out at full speed, one after the other, each tracing a long, curving line in the sand. Then the trumpets are blown, and the next fight begins.

I SAT there, in my box, from three until half-past five, when the eighth bull was killed in the halfdarkness. Two men had been slightly wounded, and ten horses killed—a total which, for eight bulls, as "II Taurino" said next day, "dice bien poco en favor de los mismos." An odor, probably of bad tobacco, which my imagination insisted on accepting as the scent of blood, came up into my nostrils, where it remained all that night. Out of the open sky a bird flew down now and again, darted hurriedly to and fro, and escaped into the free air. Women were sitting around me, with their children on their knees. W'hen a horse had been badly gored, a lady put up her opera-glass to see better. There was no bravado in it. . It was simple interest.

There were moments when that blue circle, as I turned my head away from the arena, seemed to swim before my eyes. But I quickly turned back to the arena again; I hated, sickened, and looked; and I could not have gone out until the last bull had been killed. The bulls were by no means a good "ganado"; I could have wished them more spirited. The odds are so infinitely in favor of the bull-fighter; he can always count on the pause which the bull makes between one rush and another, and on the infallible diversion of the red rag. It is a game of agility, presence of mind, sureness of foot and hand; dangerous enough, certainly, but not more dangerous than the daily exercises of an equilibrist. But there is always that odd chance, like the gambler's winning number, which may turn up—the chance of a false step, a miscalculation, and the bull's horns in a man's body. The small probability of such a thing, and yet the possibility of it; these, combined, are two of the motives which bring people to the bull-fight.

YET I cannot help thinking, suppress the "Suerte de Pica," and you suppress the bull-fight. This is the one abomination and the abominable attraction. I have" described it with as much detail as I dare, and even now I feel that I have hardly rendered the whole horror of it. Coming away from the Plaza, I saw every horse I passed in the street, as I had seen those horses with gaping and dripping sides, rearing back against the barrier, and dragged and beaten up to the horns of the bull. Well, that red plunge of horns into the living ^lesh, that living body ripped and lifted and rolled to the ground, that monstrous visible agony dragging itself about the sand; and, along with this, the rider rolling off, indeed, on the safe side, but, for the moment, indistinguishable from his living barrier, and with only that barrier between him and the horns —it is this that one holds one's breath to see, and it is to hold one's breath that one goes to the bull-fight. The cruelty of human nature—what is it? and how is it that it has struck root so deep? I realize it more clearly, and understand it less than ever, since I have come from that—"novillada" at Valencia.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now