Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowGOYA, SPANISH OF THE SPANIARDS

ARTHUR SYMONS

With a self-portrait of the Great Painter never before reproduced

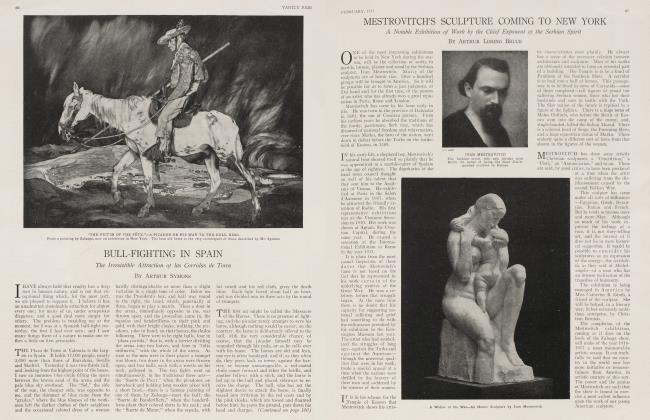

THERE are those who think that Goya was even more Spanish, as a painter, than any member of the classical Quartette made up of Velazquez, Ribera, Zurbarán and Murillo. Be that as it may, interest in what is Spanish in art has been stimulated, in New York, by the recent popular success here of exhibitions of the works of the contemporary painters Sorolla and Zuloaga. These shows, quite apart from any considerations of their own qualities, would have served a good purpose if they drove the public to a closer study of Goya, who was a Titan in every branch of art that he touched. It is a pity that this wonderful genius should be represented by so few examples in the museums of this country.

GOYA has in him — he who introduced the fantastic quality into the comic quality — a ferocious genius, essentially macabre, malignant, diabolical, stupendous as his intense scope of vision ; tremendous in his scenes in the air, his Witches and Demons and Sorceresses; dramatic in no modern sense— for the Spaniards have for centuries all but lost the sense of the dramatic—but in that elemental one which conjures up incredible abysses over unseen depths, that draws one into a positive , enchantment (not as the magician who draws spirits into his magic circle), but as a creator of tragedies unheard of, of comedies incomparable and unsurpassable, that obsess the imagination by their all but Aeschylean and Aristophanic qualities.

And his own fervent and feverish imagination has a power of evocation, of incantation, that are, in many ways, poetic; that are more than that: crammed to the brim with insane cruelties, with inconceivable atrocities, with Satanical suggestions, with horrors that outrage one's sense of human suffering; yet that are, at times, touched with a curious sense of pity: for the man can even moralize over his own emotions and those of others.

Depraved as his imagination often is—for almost always when he executes a picture of exquisite beauty, of infallible skill, of perfect craftsmanship, there comes the insidious touch that betrays his over-awakened sense of the evil that lies at the root of our existence—his genius is at once normal and abnormal. And I can but think that, on the whole, his work is more abnormal than normal. The very image of the man, as he painted himself: how unforgettable! There one sees his immense strength, his implacable will, his over-acute vision, his sinister fascination: the eyes of a lover of women and of evil spirits; the thick lips of a sensualist; and a face certainly formed into a more extraordinary fashion than that of any other painter. There, inside and outside, the canvas stands, for all time, Francisco José de Goya y Lucientes.

"VET there is no getting away from the fact that much in the expression of the face is brutal, arrogant; self-willed beyond any possible sense of self-consciousness; violent, intolerant; in a word: hideously alive to the eternal presence of two worlds, to the infernal presence of hell, to the unseen presence of heaven; abominably alive as only an animal of prodigious vitality could endure all that is terrible and delicious in every hour of life; and that in Spain no one is over-conscious of the passing of the hours.

No painter ever spent such learned fury, of so overwhelming a kind, as Goya did in his "Tauromagnia.

Goya, the Man

A FEW words about Goya, the man, may be added to Mr. Symons' estimate of the artist. One of the most interesting things about the life of Goya is its contradictions. A man of fierce independence and aggressive individuality, he spent the greater part of his career as a Court Painter. The favorite of Charles IV, the frivolous Queen Maria Luisa, and the contemptible Godoy, afterwards Prince of the Peace, he was at heart a true Radical. The son of poor but honest working people, the great love affair of his life was that with the Duchess of Alba. He lived through the Napoleonic period, but was not affected by the dramatic qualities of a twenty-year war, in the course of which kings were pushed off thrones and put back again. Indeed, so little loyalty had Goya to his sovereign that when the royalties who had made him prosperous were driven out of Spain to make place for the tinsel court of Joseph Bonaparte, crowned by the grace of Napoleon, the artist did not hesitate to take his old office from the hand of the intruder. When Charles returned he showed that he was a man of good taste and good wit by telling Goya that, though he deserved the rope, he was much too fine a painter to be lost that way, and continued him in his place.

THE terrors of war have never been set forth more vividly than in the work of Goya. Time and again, too, he showed a most un-Spanish sensitiveness to crudty and suffering of all sorts, yet he delighted in everything that had to do with the bull-ring and was fond of dressing himself up as a bull-lighter. He did the decorations for a church, and scandalized the pious by too naturalistic details that were considered unfit for such a place. In spite of the ecclesiasticism by which he was surrounded, he never lost a chance of using his irony on ecclesiastics. His characteristic carelessness for greatness was never "better shown than in the case of his row with Wellington. The Field Marshall was sitting for his portrait—the drawing now one of the treasures of the British Museum—and said something which displeased the painter. Goya seized a sword from the wall and drove the hero of a hundred fights ignominiously from the place. But the Spaniard and the Irishman soon made up and the incident was quickly forgotten.

If nothing else were left, it would be possible to reconstruct the Spain of the latter half of the 18th and the beginning of the 19th century from the work of Goya. High and low, fashionable and unfashionable, good and bad, are all there. Goya takes you as easily into his age as Daumier does into the France of his period. All his surroundings are taken up as materials and fused in the fire of his astonishing force.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now