Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowORIENTAL DANCES IN AMERICA

And a Word or Two in Explanation of the Nautch

ANANDA COOMARASWAMY

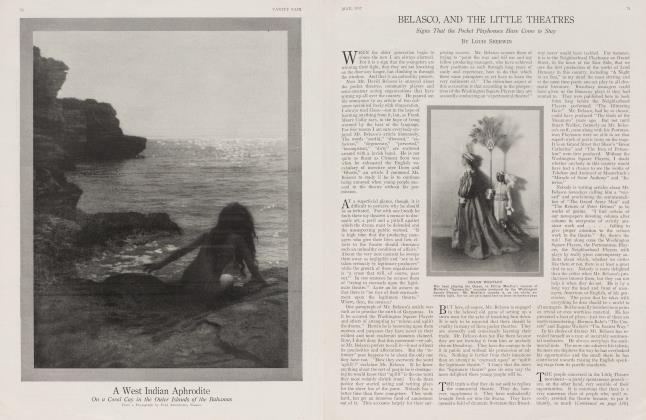

IN this country it is perhaps in dancing, more than in any other art, that one sees the expression of contemporary and national feeling. And in this adventure we can recognize at least three distinct tendencies: on the one hand the folk-art of the ball-room and cabaret; and on the other hand—on the stage— the revival of Greek movement, and the imitation of oriental art.

It is interesting to reflect that of these three, the most artistic, that is to say the most definite, conventional, and expressive, is the folk-art: while the dramatic and archaistic forms are actually far more realistic and human than their supposed prototypes in Greece and the orient. It is precisely the same with our music. It is the ragtime writer who adheres to definite conventions, and, through these, expresses the American spirit of today; while the academic composer substitutes the rhetorical accent of musical prose for the metrical accent of verse, striving after realism by the use of unusual rhythms and a deliberate disregard of law.

THOSE who succeed in the free forms of the dance, or in music, free verse, or in the realistic drama, do so by the force of their personality, rather than by art—it is themselves that they exhibit, rather than the race; and just because of this we demand, in America, the exhibition of revolutionary arts, in short, novelties. An art like this, as Mr. Lethaby would say, is only one man deep. But the greatest and most enduring art (the No dance of Japan was perfected in the 14th century, and the Indian Nautch before the fifth) has never been developed in this way: it has arisen when men have felt a need that some great thing should be clearly and repeatedly expressed in a manner comprehensible to everyone. In other words, the inspiration of great art has always been fundamentally religious (in the essentials, rather than the formal meaning of the word) and philosophic: under these conditions the theme is more important than the artist, and what we demand is a constantly repeated statement of the same ideas, until the art achieves a classic perfection. In the end, it is true, it may become a mere formula, like the Gothic formula of the present day: but in this world there is no possible condition of permanence, and those who accept the creation of an art must also accept its death. An ancient art may be a source of inspiration to us, it may guide us in matters of principle—since beauty is independent of time and place—but it ought not to be regarded as a model for our exact imitation. It is rather the theory than the practise of oriental art that has a real significance for us at the present moment. The practise should be authentic, sensitive and rare, like a beautiful museum specimen. But it is the means, rather than the end, that should be our guide to the achievement of ends of our own. Let us try to understand the Indian dance from some such point of view as this.

IT is the gods who are the primal dancers of the universe; the ceaseless movement of the world, the speech of every creature with every other, and the procession of the stars; all these are the gesture, voice and garments of the supreme Actor who reveals Himself to men in Life itself. It is from the gods, too, that human art is learnt; it is designed to reveal the true and essential meaning of our life. And so those kinds of dancing are called cultivated or classic which, like a poem, have a definite theme, while dances that are merely rhythmic and spectacular are called popular or provincial. Here we shall speak only of the cultivated dance; for the folk-dances of any country, like the folk-songs, explain themselves.

Indian culture—like that of the old Greeks— employs a single name for the common art of acting and dancing; and this word Natya, in its Indian vernacular form, becomes Nautch. Nowadays the old Indian drama scarcely survives upon the, actual stage, nor has it ever been reproduced in Europe or America; but authentic Indian acting does survive in the Nautch, where instrumental music, song, and pantomime are inseparably connected. In Nautch dancing "the song is sustained in the throat, the theme is demonstrated by the hands, the moods are shown by the glances, and the metre is marked by the feet." A set of one or two hundred bells is worn on each ankle. The construction of the dance is very definite—so many movements to so many beats; and, more than this, each gesture has a definite meaning. An Indian handbook of dramatic technique consists of a dictionary of gesture; we have twenty-four movements of the head, forty-four glances, six movements of the brows, twentyeight single hands, twenty-four combined hands, and so forth. Each of these gestures, like a word, indicates an emotion, object, idea or action; so that a sequence of gestures makes a sentence, and an entire dance tells a story. As we said before, this gesture language is constructed on definite metrical patterns, like a poem; and by contrast with this, modem western acting and dancing exhibit the characteristics of prose.

THE constant theme of the modem Nautch is mystical, the love of Radha and Krishna—Radha, a milkmaid of the little village of Brindaban, and Krishna, the Divine Cowherd. Radha and her companions, beautiful and passionate and shy, are the souls of men; Krishna, the thief of hearts, is the incarnation of God. As the milkmaids go about their daily tasks he lies in wait for them on the forest paths or by the ferry; the sound of his flute calls them to neglect the duties and preoccupations of their world in order to follow him—and this drama of seduction, which is so near to the realities of life, and reflects the spiritual experience of liveryman, is the dominant theme of mediawal Hindu painting, poetry and pantomime.

Of American dancers, Ruth St. Denis has reproduced the atmosphere of Indian life and feeling with marvelous sensibility and art; but it is only Roshanara, associated with Ratan Devi, who has presented this season on the New York stage for the first time in America, what can rightly be called an authentic Nautch. Here is the story of Roshanara's Nautch: Radha goes out to milk her cows; and as she trips along she hears the flute, and says to herself, "That must be Krishna." She describes him, but she does not see him. She finds the cows, and fills her bowl with milk and sets it on her head and takes her way to the market place in a mood of entire satisfaction with herself and with the world. But Krishna has followed her, and he takes a little pebble and throws it at the earthen bowl on her head and shatters it—for Radha must not feel secure in the possession of her worldly goods. The milk pours down on her, and she is very angry; she wipes her face with the end of her veil, and, looking up, she sees Krishna. He catches her by the wrist, but she breaks away and dances off unscathed. For the time she has escaped: but the drama is eternal, and there shall come a time for each of us when love is heard. It is in this way that the Indian dancer, in describing the mutual relations—in the narrative she is interpreting—of a hero and heroine, reveals an esoteric meaning to us in the gestures and posturings of her dances.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now