Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe World Re-made

But Have We Re-Moulded It Nearer to the Heart's Desire?

GEORGE S. CHAPPELL

READER,—at the outset, let me ask you a pointed and perhaps painful question. Have you a little regenerator in your midst? Do you feel, within yourself, a striving toward the higher life; the desire of the moth for the overcoat? Do you resolve, with the immortal Barnum, to be greater, grander, bigger, better than you ever were before?

If not, Reader, this article is not for you. Lay it down and go your frivolous way; tread the primrose path—if you still have credit at Thorley's (adv.) but remember, primroses are devilish expensive at this time of the year and a day of reckoning will surely come.

And let me tell you, further, you are very much in danger of waking up in bed some morning to find yourself hopelessly out of it . . . not out of bed, mark you, but out of everything else. Dear me, my idea gets more hopelessly astray ever)' time I try to phrase it. Let me make a fresh start.

WHAT I am trying to say is that regeneration is the order of the day. It is a by-product of the great world conflict.

But you must have felt it. It is everywhere, this spirit of uplift and idealism. A glance at the menu of one's club— whether Union or Colony—is enough to convince one that the days of plain living and high thinking, much giving and no drinking, are upon us.

Nor is this all.

The moral revivification runs the entire gamut of our social activities. Where, for instance, are the charming little dinners you used to have at the TurbotTrailers, the canneton a la presse, the bottle — one, only — of excellent Burgundy and the good, long cigar?

Gone,, gone!

The Turbot-Trailers have both been regenerated. They are up to their ears in it. Phil— good old boy—is collecting a perfectly colossal sum among his banking friends, to purchase camp-chairs for the camps. He says the present condition of things is shocking—loads of camps and no camp-chairs—no one thought of it, apparently; and, as for Lucy, his charming wife, she is so immersed in war savings stamps that she never thinks of dining,—hardly of lunching. Only yesterday when I begged her to run into Sherry's for a little bite, she said, rather tragically, "I have lunched. Look." And she held out her slender hand and showed me that her usually glistening nails were absent.

"But, Lucy!" I protested, "you are carrying this thing too far; surely there is no nourishment in . . ."

"No, no. You don't understand," she interrupted. "I don't eat them. I break them . . . at the Automat."

Doesn't that prove to what heights,—or depths—the spirit of self-sacrifice will carry one?

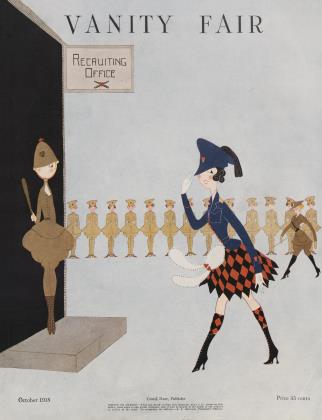

It's the same way with clothes.

They are not being worn any more. That is, the real, glitter), Christmas tree things have given away entirely to the plainest possible frocks, or to business-like uniforms* with as many pockets as a filing cabinet.

As for dancing,—well, dancing is stone dead, as ever)' one knows. Our fair partners in the latest form of waltz or one-step have plunged into the serious occupations of life. They are early to bed and early to rise; and up betimes at their study of nursing, or stenograph)', or canteening. I wonder what sort of nurses and stenographers they will make. Sometimes I am doubtful of the wisdom of it all. They are so beautiful, these lovely ex-partners of ours, that I am afraid their mere presence may get the hospitals and the general staffs horribly mixed up about their home duties.

However, there it is! That is the situation, and we must accept it. More than that, we must join in with the movement or become hopeless back-numbers.

SUCH a striking instance has happened in my own family. My aunt Emma, whom I only mention because she is rather a type, is a person who has been brought up, spiritually, in cotton wool. No breath of adversity has ever fanned her false-front or touched the fringe of her dolman. Yet, with it all, she used to be the most consistently acid aunt I have ever had. My brother Peter once said to her: "Aunt Emma, you have the most even disposition I have ever known. You are disagreeable all of the time."

It was quite true, then.

But note the sequel. At the very outset of the great war, Aunt Emma was caught in the great blast of regeneration. Being of rather light weight, she was among the first* to go, just as dry leaves dance along in front of a tornado before the business buildings begin to follow in their train. She heard a sermon one Sunday on the great world-purification that was going on, and she came home a changed woman, From that time on, she decided absolutely that everything was for the best and that she would forever after look only on the bright side of things.

Frankly, it made me rage. When, one morning, she went so far as to say, after the destruction of the University of Louvain, that probably some of the books in the library were no better than they should be, I saw red and hid her glasses. We had shad for luncheon that day, too, but I think I was justified.

And now! now that the tide has turned and things are going the other way, in France, by Jove, I have to agree with the old lady—and that is almost as maddening as disagreeing with her.

THEN again, look at the men like Tipworthy who used simply to live in the club—bar. I give you my word he was never out of it, except when the night shift came on, carried him to the coat room, put one brass check in his lapel and laid him on his side in a cool, dark place. He was so valuable a member of the organization that the Governors created a special office for him. They made him chairman of the Souse Committee.

Withal, Tip was a genial old soul, and not without his uses. There were always people swinging into town from the West, eager for companionship and guidance. Most of us have to go the rounds with a friend of this sort once or twice a year. We know how wearing it is, and how our wives don't speak to us for days afterwards. But Tip solved all our problems for us. We simply turned the visiting firemen over to him. He met all comers without a quiver, entertained them royally and sent them back to the timber-lands firmly resolved to be better boys.

Tip was really an institution.

Well, one day, he saw the writing on the wall, and what the writing said was "Prohibition! bone-dry Prohibition!" He didn't like it at all, but, do you think he quailed? Not a bit of it. It simply regenerated him. He disappeared. The club knew him no more. I met him yesterday looking as spruce and fit as the young men in the clothing "ads" who always stand with one foot on the running board of a touring car.

"For Heaven's sake, Tip," I said, "where have you been?"

His glance was as firm and steady as a cherry stone clam as he replied: "I'm taking the gas course up at Columbia. They try the new ones on me. They find that I can stand anything."

Think of it! What a wonderful use to put his talents to! To devote them to the interests of humanity. And how many more there are, like Tip, who could be similarly employed—to the advantage of society ai large?

Continued on page 104

Continued from page 69

EVEN more subtle has been the spiritual change which has affected such a countless number of lives; the great cure-ell, calming hand that has been laid on all sorts of domestic strifes and bitternesses!

I think I was never more affected in my life than on my last visit to the offices of the Czecho-Slovak Relief Fund. The Czecho-Slovaks, you know, are the very latest thing and every one really worth while is working for them. I think the idea is to relieve the Slovaks of the Czechos, or something of that sort. Well, at any rate, I went boiling into the office one of those hot days last month and who should I bump into but Ned Hartpence, whom I hadn't seen since he ran away with Nellie, my Cousin Egbert's wife.

Naturally the sight of Hartpence brought me up all standing. But I wish you could have seen his face when he saw me. Not a trace of embarrassment, not a tremor or a blush. He just beamed. I saw right away what had happened. He was being regenerated. Fate, operating through the Czechoslovaks, had touched him on the shoulders and he was transformed. He had that syrupy manner, which goes so big with country congregations, and a sort of New Republic light in his eyes.

"George!" he exclaimed softly, "George! Are you with us, at last ?"

I realized that it was a new Hartpence who was speaking to me.

"You will like the work," he said, with quiet enthusiasm. "They are a wonderful people, the Czecho-Slovaks. If we can only remove the hyphen it will help a lot. It is the same with the Jugo-Slavs."

He sighed wearily as if the weight of Atlas rested on his shoulders, then brightened as his mind turned to happier things.

"We have such cheerful quarters here," he continued, raising the/ shade. "See, I look directly over old St. Paul's churchyard. I can almost read the epitaphs. And, in my inner office ... ah ! I have a great surprise for you!

He tiptoed to a glazed door and swung it open softly. Ye Gods 1 what a picture met my gaze. Seated at a mahogany desk, purchased for the relief of the Czecho-Slovaks, was Nellie, and facing her, slightly crouched, was my cousin Egbert.

"Please take some dictation, Egbert," said Nellie, crisply.

"I always have," said Egbert with the ghost of a smile.

It was too much. I closed the door noiselessly and fled.

IT was all too beautiful. There are some things so delicate and loVely, some reconciliations so touching, some depths of self-effacement so great that they are painful to dwell upon, particularly when they occur in one's own family. But who can say that they are not great, and that the world is not sweeter and cleaner for their being?

Not I, for one.

No, Reaider, strange as it may seem, I, too, poor, weak I, have felt this great upward impulse. I tremble at it. It fills me with awe and a sense of unworthiness, but it will not be denied. Frivolities to which I used to run with the glad yelp of a Sioux Indian I now pass by with a downward and averted glance. The sirens may sing as they will, but my ears are both stopped with medicated wool. The red paint and the paint-brush, once used for civic decoration, lie idle in my cupboard. The odor of primroses is distasteful to me.

"Strange, strange metamorphosis!" I think as I take my last look at the mirror before hurrying to my thrift stamp booth: "Can this indeed be you!"

Yes, strange it is, and a bit cold and lonesome at times. But I console myself with one thought,—the cloud has a silver lining. Such world goodness cannot last forever. A great deal of it must be just for the duration of the war. In other words, wc are not serving a life sentence. Will not a terrific scraping sound arise, the day after peace has been declared, a sound as of some hundred million people softly backsliding? I rather think there will.

But I am inclined to agree with Aunt Emma, that it will all be for the best.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now