Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowBoris Anisfeld: Fantast

CHRISTIAN BRINTON

Je peins ce que je sens, pas ce que je vois

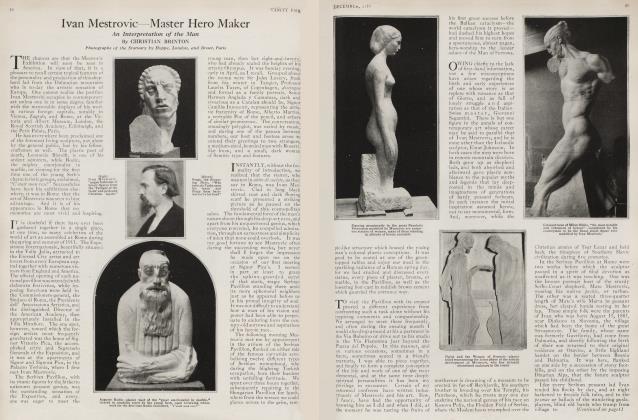

THE sudden appearance in America of the distinguished Russian decorative painter, Boris Anisfeld, affords what is certain to be the artistic sensation of the season.

More like romance than reality is the story of his escape from revolutionary and famine-ridden Petrograd, and his flight over the Trans-Siberian railway to Vladivostok, and Japan, with his family and a series of canvases representing virtually his entire life work.

Not a little perturbed by his recent painful experiences, Anisfeld is now in New York. His paintings will be seen next month at the Brooklyn Museum, and, later, in the leading art museums of the country.

WHEN, a scant decade ago, the Russian Ballet flung across the artistic firmament its first effulgence, the general public in Europe considered it a purely exotic phenomenon. Those only familiar with Russia because of the sermonizing of Tolstoy, the stark pathology of Dostoevsky, and the peace propaganda painting of Vereshchagin were ill prepared for this exhilarating fusion of color, sound and movement.

By the close of a brief, triumphant season—it was at the Chatelet in 1909 —the conventional, West European conception of the Slavonic temperament had been made to undergo a change because of the free enjoyment of a Russian art, direct, synthetic, and sensuous—the art of the choreodrama. As though by magic, one was transported from church, courtroom, and clinic into a wonder world of romance and passion, to Samarkand and Bagdad, to Persia, India, and China. The tyranny of the actual was broken. The soul tortures of Anna Karenina vanished before the exultant seduction of Semiramis, Zobeide, and Salome. What was of chief importance, however, was the fact that a new art form had come out of the East bearing, Magi-like, its bountiful offering.

WHILE, in the popular mind, this Russian transformation took place over night, as it were, the moment was long preparing. Contemporary Slavonic art, of which the ballet is but a single phase, represents, in common with all art that is vigorous and vital, the relentless process of reaction. For you will fail to grasp the significance of modern Russian art, in all its color and complexity, if you do not bear in mind the fact that it constitutes a protest against realism, a triumphant renaissance of the ideal, or, to be more explicit, of decorative idealism.

WITH the founding, in Petrograd, of the review known as Mir Iskusstva, or The World of Art, and the exhibitions given under the auspices of the society bearing the same name, came the end of the old regime in Russian art and the dawn of a brighter day for Russian taste. The two men whose names stand forth as having initiated this veritable rebirth of Slavonic art are the impresario, Serge de Diaghilev, and the painter, critic, and directeur artistique, Alexandre Benois. They were the fugelmen of the new dispensation. They stood ever in the forefront pointing the pathway, if not of aesthetic salvation, at least of aesthetic redemption.

Around Diaghilev and Benois rallied all the abler spirits. The refined eroticism of Somov, the rococo romanticism of Lanceray, the severe archaism of Roerich, and the fertile eclecticism of Bakst flourished abundantly during the succeeding decade. The field of book illustration welcomed a new master in the stylistic Bilibin, while the wanton graces of the eighteenth century were revived by Benois, who labored with brush and pen. Each and all, they were retrospectivists— enemies of realism. In order the better to convey their message they drew upon the treasury of the past. Every epoch and every stratum in the cultural history of their country was turned to good account. And thus was the glaring noontide of Russian national realism succeeded by the afterglow of a national idealism, delicate, ephemeral, and eloquent of half-forgotten things.

The crowning triumph of this efflorescence was found in the Ballet Russe, the focal point of all the arts, and it was to this very ballet that one of the youngest recruits to the ranks of the Petrograd group—Boris Anisfeld, the painter —dedicated his exotic fancy and seething flood of color. Into the effete, aristocratic atmosphere of the capital came, in short, a man who was destined to contribute to the art of his day two distinctive notes, the note of color, and the note of creative fantasy. It is obvious that color and creative fantasy were characteristic of Russian painting before the advent of Anisfeld, but he intensified this color, and added to this fantasy an unwonted luxuriance.

The visual creator of The Marriage of Zobeide, of Islamey, Sadko, and The Preludes, the painter of grey, spirit glimpses of the Neva, and sun-scorched stretches of Syria or Palestine, was born at Bieltsi, in the heart of Bessarabia, on October 2, 1879. His father was a landed proprietor of means, possessing a large estate. The boy, at a very early age, showed a strong bent for drawing.

AT the age of sixteen, the young man determined to devote himself to the study of art. He encountered none of the customary parental opposition. He left his family home and passed five years of artistic apprenticeship at the Odessa School of Art, where his masters were Ladij insky and Kostandi. He worked with zeal, and, by 1901, when he left to complete his training at the Imperial Academy of Fine Arts at Petrograd, he was already familiar with the technique and practice of his profession. He-had tried his hand at everything. He painted landscape, figure, and decorative composition, and handled with assurance, crayon, oils, tempera, water-color, and pastel.

Possessing accuracy of observation and keen visual sensibility, the initial canvases of Boris Anisfeld—after leaving the Imperial Academy —were not distinctively imaginative in appeal. They were, rather, temperamental transcriptions of nature; subtle, decorative, almost Whistlerian in feeling. These early canvases were brought to the attention of Serge de Diaghilev, who was then assembling his notable collection of retrospective and contemporary Russian art. Diaghilev, with his habitual penetration, at once selected a group of canvases for his picture exhibition which, by the way, proved the success of the artistic season of 1905. It was the following year that witnessed the Parisian triumph of Anisfeld at the Salon d'Automne, and although an entire newcomer, he had the distinction of being elected a Societaire of this enlightened organization.

THE same season that saw Boris Anisfeld's success in Paris as a painter of sensitively viewed landscape effect, marked his triumph in Petrograd as a master of stage decoration, the initiator of a new genre, the predecessor, in point of fact, of the ubiquitous Bakst and the entire school of Russian scenic decorators. A tout seigneur, tout honneur, but it is nevertheless indisputable that when Anisfeld's setting for Hugo Hoffmannsthal's Marriage of Zobeide was disclosed at Mme. Vera Kommissarjevskaya's Dramatic Theatre something had been added to the sum total of Slavonic art. A Persian fantasy in three acts, the play afforded Anisfeld the opportunity he had long been dreaming of. Into its artistic investitude he poured the wealth of his fundamentally oriental temperament.

So novel and striking were the chromatic and stylistic qualities he displayed on this occasion, that once more was the discerning attention of Diaghilev turned toward the young Bessarabian, with the result that he was commissioned to undertake some of the most important creations of the Russian Ballet. From this date onward the story of Boris Anisfeld's career unfolds itself with unbroken uniformity. The Marriage of Zobeide was succeeded by numerous special scenes for the Diaghilev ballet executed wholly by Anisfeld, for he is one of those born craftsmen who are not content to turn their sketches over to alien hands. In 1909 came his decor for Ivan the Terrible, while the season of 1911 saw the production of Sadko at the Chatelet, in Paris, and afterward at the Imperial Maryinsky Theatre, in Petrograd. In the latter instance Anisfeld designed costumes as well as scenery and, in consequence, the production was a complete and unified affirmation of his personality. Sadko was followed by the premiere of the Anisfeld - Fokin version of Balakirev's Islamey, also at the Mary insky Theatre, a spectacle that won the unstinted praise of the Petrograd critics, notably of Volinsky, a valiant champion of the more advanced phases of artistic expression. And after his Islamey it is merely necessary to record the success of The Seven Daughters of the Ghost King, the Freludes, and similar productions seen in the leading cities of Europe and America.

YET it must not be assumed that Boris Anisfeld, during these busy, creative years did not stir from Petrograd. He is a persistent and intrepid traveller. His own country he knows from end to end, from the Caucasus to Finland, from Pinsk to Perm. In 1906 he went to Paris to attend the exhibition of Russian art at the Grand Palais, and—in every succeeding year until the war—accompanied the ballet on its triumphant tours in order to supervise his own productions. He has visited, in turn, most of the countries in western Europe.

While from these journeys he brought back fresh pictorial impressions, canvases revealing a personal, coloristic viewpoint, Boris Anisfeld's chosen sketching ground is the impalpable kingdom of fancy. It is mot when confronting fact that he feels most at ease, but when calling into play those aesthetic atavisms that so indubitably condition his creative consciousness. An Oriental by ancestry and spiritual heritage, he possesses that faculty which belongs to those who, young or old, see visions and dream dreams. It has been the fashion of certain Petrograd critics to aver that he is an artistic descendant of Giorgione and the Venetians, Paolo Veronese and Tiepolo. The diagnosis is not alone superficial but fallacious. It is not these masters, nor yet the Frenchmen, Monticelli or Odilon Redon, that he suggests. Idealistic and decorative though it manifestly is, the inspiration of Boris Anisfeld harks still farther back, back to sources not Latin or Attic, but Asiatic. Its home is not the Ile de Cythere, but the purple hills of Palestine and the hanging gardens of Babylon.

Continued on page 110

Continued from page 71

There is, in the work of every artist, a certain unity, latent or conscious. No matter what changes or transformations he may be subjected to, he can never escape his inalienable birthright. Survey, for example, the production, still fragmentary and incomplete, of Boris Anisfeld, and you will not fail to discover the secret force that binds together his every effort. The imaginative fervor, the sumptuous tonality, the love of jewel-like surfaces, strange beasts, birds, fruits, and luxuriant foliage all point toward the seductive East rather than to the ordered, rationalistic West. Profoundly influenced as Anisfeld was in his youth by the Scriptures, you need not be surprised at encountering here such apparitions as Rebecca at the Well, or the Shulamite chanting her ardent love song. Out of the Garden of Eden he fashions a pictorial fantasia all green and purple, while in The Golden God we find traces of that frenzied image worship which will never, it seems, be wholly eradicated. And apart from subject and theme, the reverberating color chords of these compositions are oriental. Color is indeed their chief glory, their main reason for being.

This symphonic fantasist, who literally plays with lapis lazuli, emerald, and deep, clanging reds and yellows, is a modest, retiring individual. Unless you had followed his career abroad, or were fortunate enough to induce him to talk, you would never realize that he was represented in virtually every important public and private collection in his own country, and had won the acclaim of a dozen or more European capitals. His experiences in Russia during and after the war, his hasty exodus to America, and final landing in the feverish activity of New York have for the moment left him a trifle bewildered. Yet although, as he picturesquely phrases it, "The Muses are silent when the cannons boom'*, he was fortunately able to paint quite a little in his spacious studio in the Petrogradskaya Strona before his departure. And it is the fruit of this stressful period, as well as considerable early and also later work that America will shortly see and pass judgment upon.

AN admirer of such visionary spirits as Whistler and Edgar Allan Poe, Oscar Wilde and Verlaine, as well as the enigmatic Easterners, Anisfeld nevertheless moves in the world of pictorial symbolism with a certain satisfying surety. The two elements which, above all, he strives to attain in his paintings are color and form. "I always see a thing first in color," he says. "It comes to me as a complete conception, and I rarely have to alter the essential character of any of my initial impressions. It is my habit," he continued, "to put down these visions of color and form, such as they are, quite rapidly, and to amplify and intensify the scheme at some later time 'when I am so disposed. With me art is a matter of feeling and I paint, as a rule, that which I feel, not that which I see."

His art is a product of emotion and imagination rather than reason and observation. Essentially Russian in their mysticism and psychic complexity, there is something festal and carnivalesque about these big, freely brushed pictorial syntheses, and these gleaming little water color panels. His art appeals primarily to our sensibilities.

When confronting the productions of Boris Anisfeld it is well to resign one's self to the subtle potency of the spirit and the senses. The art which lasts longest is that which, like Anisfeld's, displays the greatest measure of intensity.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now