Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowRussia's Latest Artistic Celebrities

Critical Notes on the Painting and Decorative Designs of Goncharova and Larionov

CHRISTIAN BRINTON

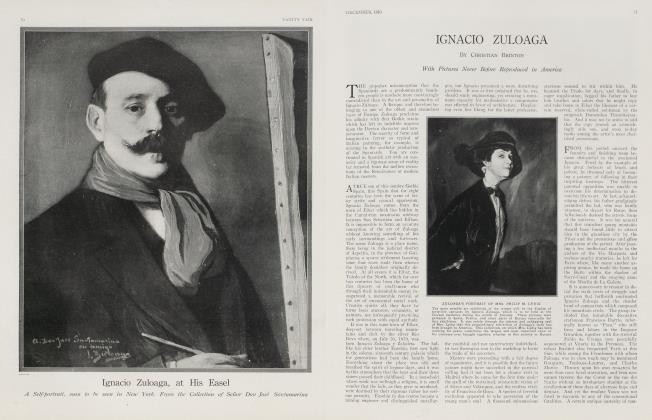

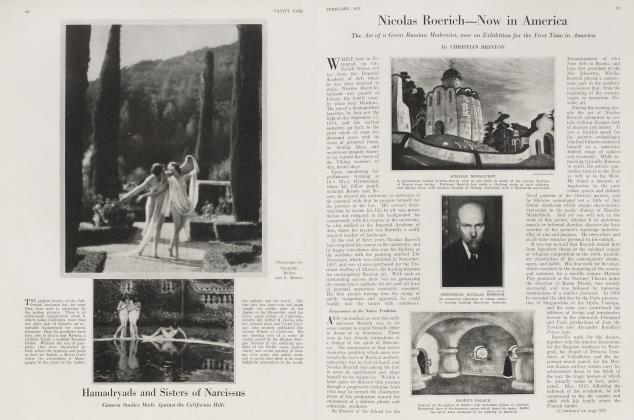

THOSE of us who, a decade ago, considered Bakst and Benois the apogee of all that was daring and progressive in the way of stage decor and costume, are today compelled to revise our estimate of the Ballet Russe. Since the production of Scheherazade, and Petrushka these fertile Russians have in no sense been resting on their laurels. Fresh luminaries have lately flashed across the horizon, and there are at present new names to conjure with.

There seems indeed no limit to the creative fecundity and colouristic fervour of these same Slavs. Bakst, Benois, Anisfeld, Roerich, Serov— one by one they pass in review, each bearing the stamp of a distinctly endowed personality and the boon of a rich racial patrimony. The sensuous neoclassic evocations of Bakst, the gracious eighteenth-century inspiration of Benois, eloquent of Peterhof and the parks and gardens of Versailles, the oriental fantasy of Anisfeld, and the remote, northern archaism of Roerich are familiar to us alike on exhibition wall and across the footlights.

These men, together with their colleagues, Korovin and Golovin, belong, however, to what we may designate as the first phase in the evolution of contemporary Russian stage decoration. They are not, strictly speaking, modernists in their attitude toward the problem in hand. It has been reserved for newer talents to carry forward the work they so triumphantly initiated, a task that is to-day being accomplished by Goncharova, Larionov, Alexandra Exter, Kuznetsov, the diverting Sudeykin, and kindred progressive spirits.

Futurist Decors

IT is to the credit of Goncharova and Larionov that they should have been the first painters to apply the principles of cubism and futurism to stage setting and costume. When, in May, 1914, Goncharova's version of Le Coq d'Or was seen at the Paris Opera, it was at once conceded that something new had transpired in the realm of scenic presentation. The success of Goncharova's Le Coq d'Or was supplemented the following season by Larionov's Soleil de Minuit, and in 1917 Larionov attained still more original and striking effects in his Contes Russes, which was first offered at the Chatelet.

Sudden as was the apparition of these two artists, and sensational as was their debut, it must not be assumed that their position had been one achieved without due preparation, or that logical sequence which is the prelude to solid achievement. To those fortunate enough to be familiar with artistic affairs in Russia, they have long been known as courageous modernists, and it is the specifically modern note which is the characteristic feature of their contribution. Side by side they have fought for the acceptance of the new in art, and the battle which began a dozen or more years ago in Moscow has finally been won in Paris and London.

The daughter of a distinguished architect and a great grandniece of the poet Pushkin, Natalia Sergeyevna Goncharova was born on a typical Russian landed estate in the Government of Tula. On her father's side she is descended from a noble family, already rich and influential in the reign of Peter the Great, while her mother's family, the Bieliaevs, have long been prominent in ecclesiastical circles. Her childhood was passed wholly in the country, where she learned to know and love nature and the local peasant life, so rich in colour and so permeated with religious mysticism and artless fantasy. After some years in this district, she moved to the great family manor house in the Government of Kaluga, with its two hundred or more rooms and walls hung with stately ancestral portraits by Borovikovsky and Levitzky.

Possessing such a background, it is remarkable that Natalia Goncharova should have become an ultra modernist, yet it was not long after leaving the Moscow Academy of Art —where she remained some four years—that her progressive tendencies became manifest. At first devoting herself to sculpture, which she studied under Prince Paul Trubetzkoy, she subsequently turned to painting, her initial exhibition taking place in 1904 under the auspices of the Moscow Literary and Artistic Circle. Her association with Larionov gave her courage and conviction, and together they began a campaign for aesthetic freedom.

The Growth of Goncharova's Art

IT is superfluous to trace step by step the unfolding of Goncharova's pictorial genius. At each appearance she manifested increasing vitality of vision and statement. Together with Larionov she passed through the successive stages of post-impressionism, cubism, and futurism, finally discovering her most congenial expression in rayonnism, the latest product of Larionov's restless creative consciousness. Co-founder of the Knave of Diamonds, The Target, The Donkey's Tail, and kindred revolutionary groups and coteries, they periodically displayed their work before the bewildered Moscow and Petrograd press and public.

And yet along with so much rapid absorption of that which was new lurked certain fundamental characteristics that lay deepanchored in bygone days. Natalia Goncharova's inspiration looked forward on one hand to the brightness of the visible universe, and backward to the solemnity of the Orthodox ritual, the early ikoni, and the primitive wall paintings in the blue, green, and gold-domed churches and cathedrals of Kiev, Novgorod, and Vladimir. To the pious ecstasy of the past, she adds the questing aspiration of the present-day world. She is at once a child of light and progress, and a messenger from that dim, hieratic realm which exercises its spell over every true Slavic soul.

Continued on page 88

Continued from page 56

Mikhail Feodorovich Larionov, the founder and acknowledged head of the modernist movement in Russia, while born in the south, in Bessarabia, is descended from Nordic stock, his father having been a prominent physician from Arkangelsk. The energy, the power of organization, and the gift for leadership so typical of the north are exemplified in Larionov, who passed his school days and received his artistic training in Moscow.

Of all the young Russian rebels who flaunted their originality real or fancied in the face of their aghast elders, Larionov was the most uncompromising, the most aggressively militant. Dismissed from the Moscow Academy for reasons sufficiently conclusive, this enfant terrible of brush and palette proceeded to travel, to paint with prodigal energy, and to pass with protean rapidity from one formula to another. And yet this veritable anarch of art, who used actually to don a cubist costume and decorate his physiognomy in keeping, possessed serious attainments, and a genuine capacity for organized expression.

Joining his regiment at the outbreak of the war, Larionov was severely wounded at the battle of the Masurian Lakes and subsequently settled in Paris, where Goncharova and he quickly won a distinctive position with the prominent modernists of the day, counting among their circle not only painters and sculptors, but men of letters and musicians as well.

Various important exhibitions of their work held in Paris, London, and elsewhere, together with numerous stage productions have served to define the aims and achievements of Goncharova and Larionov. Both are naive and primitive, as well "as modern and complex in their inspiration. The one reveals a rare creative fecundity and a wide range of artistic sympathy. The other is distinctly cerebral and endowed with a remarkable instinct for decorative synthesis. Goncharova assimilates and combines. Larionov analyzes and reduces colour and form to their essential components.

In his Contes Russes, and still more conclusively in his Le Bouffon, with music by Prokofiev, Larionov proves himself a master of the newer phases of stage presentation. His work here displays an integrity of line and tone combined with a sense of dynamic movement which give it unique vitality. The element of movement—movement not alone of the figures themselves but that mysterious vibration of structural forms and basic colour notes which he calls rayonnism, is in fact Larionov's chief legacy to the art of the presentday stage.

It is a significant fact that no matter how far Gonchorova and Larionov proceed along the pathway of modernism, they never forget their original point of departure. You will note in the varied pageantry of this art echoes of massive lavra and humble izba. You will meet austere apostle and ribald clown from rural fete, the spear-scarred cheek of the Iberian virgin and simple painted toy.

Possessing such a heritage racial and aesthetic they are well equipped to embrace the more conscious expression of the contemporary school. Their work, in whatever medium, is always colourful, instinct with creative joy, and typically Slavic in spirit.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now