Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowJuan Belmonte, Greatest of Matadors

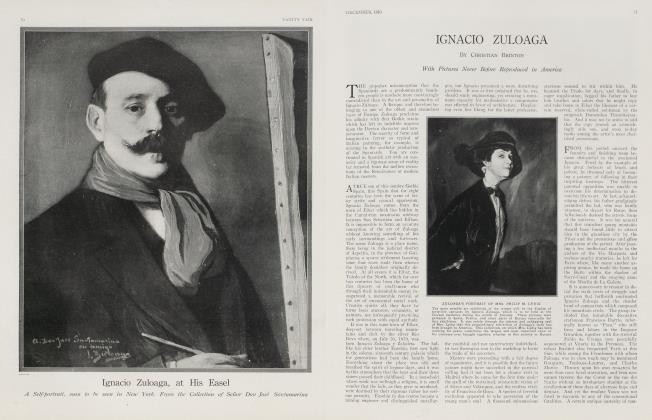

An Account of the Man—and the Artist—by his Friend, Ignacio Zuloaga

CHRISTIAN BRINTON

Editor's Note: Juan Belmonte is perhaps the most famous torero of all time. The following account of him was obtained by the writer from interviews with his friend, and ardent admirer, the Spanish artist. Zuloaga. now in this country, and also from his wife, Madame Belmonte.

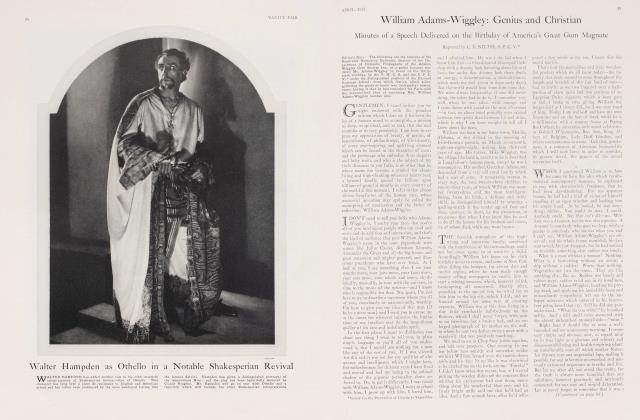

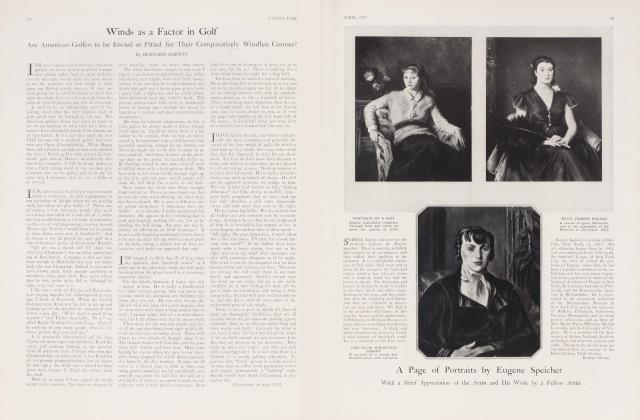

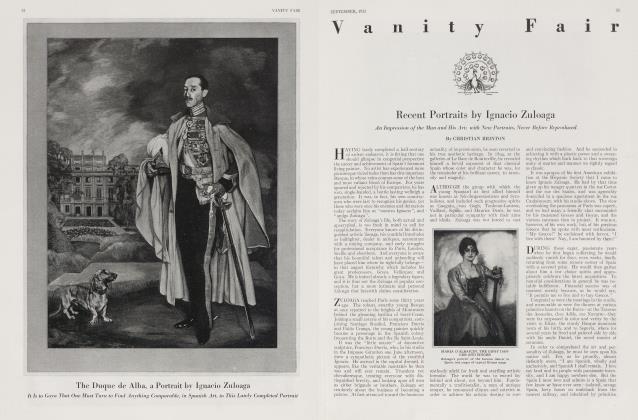

VISITORS to the phenomenally successful exhibition of paintings by Ignacio V Zuloaga, which drew to the Rheinhardt Galleries seventy thousand aficionados—Spanish for "fans"—within four weeks, displayed particular interest in the three full-length portraits of the celebrated torero Juan Belmonte _one in gold, one in black and one in silver. Zuloaga had painted bull-fighters before. They have always been favourite subjects with the artist, who himself used to fight as an amateur. Yet never before had he exhibited at one time three likenesses of the same individual. The reason for his so doing is not far to seek. Zuloaga and Belmonte are devoted friends, each warmly admiring the other's profession. And each, in his way, is a national idol, Zuloaga being Spain's leading artist of native scene and character, and Belmonte his country's foremost matador. What then, could be more natural and appropriate than for Zuloaga to depict the form and features of this man whose technique in the arena rises to supreme heights of physical daring and genuine aesthetic expression.

TO visit Spain without tending the corrida de toros is as bad as to go to Russia without eating caviar and drinking vodka. Unparalleled in the fetes of the world is the fiesta de toros. Stretching back through shining centuries of courage and chivalry, the corrida maintains as firm a hold as ever upon the passions of the populace. Spain minus the corrida would cease to be Spain. Without bull-fighting, without the ringing cries of Buen toro, and Hulel llule! Spain would be comparable to our country without baseball and football!

Typifying in its elements the eternal struggle between man and beast, the corrida has gradually assumed the significance of a superb national spectacle, at once gorgeous in its color effects, consummate in its artistry, and vivified by the crimson splash of primitive animalism. While antipathetic and officious foreigners are sometimes prone to condemn certain aspects of the bull-fight, such an attitude indicates an imperfect comprehension of what constitutes true race psychology. There is in point of fact scant use in prating against the corrida or any characteristic feature thereof. The royal edict of Isabel la Catolica, the papal bull of Pope Pius V in 1567, and the interdiction of Fernando VII in 1814, each signally failed to put an end to the sport. Pan y toros—bread and bulls—had too long been the slogan of the Spanish people.

Bull-fighting as it is practiced today developed during the first half of the eighteenth century, the matador eventually rising to a position of such importance in public esteem that Goya was proud to paint two famous bull fighters of the day—Romero and Costillares. Francisco Romero, a former shoemaker of Ronda, was the first professional fighter of bulls, and the prototype of that long line of daring and picturesque combatants that for two centuries have thrilled the Peninsular populace with their prowess in the yellow-sanded arena. At the outset there were two distinct schools of tauromachy, the Rondenian, founded by Romero, and the Sevillian; but gradually the Sevillian type with its elements of nonchalant swagger and cool daredeviltry became the prevailing mode.

It was Costillares who, with fine pictorial sense, fixed the accepted types of dress for the different categories of bull-lighters. Legartijo and Frascuclo became the chief exponents of the classic school of bull-lighting. Yet everything they had (forgive the sporting idiom) and much more beside was embodied in the transcendent dexterity and incomparable plasticgrace of Rafael Guerra, popularly known as Guerrita. It has been the privilege of the present writer to witness Ricardo Torres—Bombita II—dispatch many a dreaded Miureno bull. Gaona we knew and admired in Mexico before assisting at his trying debut in Madrid. Machaquito, Vicente Pastor, Algabeno, Gallito —all however fade into insignificance before Juan Garcia Belmonte, the young Sevillian who has virtually founded a new school of tauromachy.

EVERY artist of courage and conviction, whatever his chosen medium of expression, takes something from tradition and adds something to tradition. In the graceful though bv no means gentle art of bull killing, we have Martinho to thank for the hazardous pole-vault over the bull's back. Gaona discarded the will eta, instead deftly turning his body and letting the enraged animal plunge furiously past him to right and left. But these and similar innovations have been utterly eclipsed by the novel and daring tactics of Belmonte.

The contribution of this slender young man, who, though still in his early thirties has dispatched over three thousand bulls, marks the advent in the arena of that disturbing element known the world over as modernism. He has clipped his co/eta—the pig tail, most sacred symbol of his profession, has thrown aside, with it, all previous conventions of his craft, and has achieved that which no man ever before attempted in the sunflecked arena.

"It is impossible," say his friends and compatriots, Zuloaga and Benito, "to describe the torero, or, as we would call it, the play, of Belmonte without dropping into an untranslatable maze of technical terminology. All one can say is that he is "el nuevo fenomeno" of the corrida —something wholly and entirely novel in the annals of bull-fighting. When, for instance, he settles down to the real business of playing the bull before the actual kill, he permits the animal to approach much closer than any matador has previously done. He stands in fact almost directly between the horns, quite inside the arc described by these swift-stabbing messengers of death. Other fighters step dexterously from side to side as the bull dives desperately at the flaring and deceptive capote, or cape. Belmonte, on the contrary, remains virtually in the same spot as before, merely extending his arms and swaying his flexible body as occasion requires. He calculates his distance from the fateful, fast moving horns with fractional accuracy. The crowd holds its breath in anguished suspense.

(Continued on page 108)

(Continued front page 49)

The hull's horns seem to be boring into him. But with an intuition which is positively uncanny, he seems to know precisely what the bull will do-, and adjusts himself to the situation with instantaneous spontaneity. Most remarkable of all, however, is his incomparable physical courage—his utter disdain of danger. It is this supreme quality that so endears him to the masses, that gives him a prestige almost supernatural in the eyes of the adoring people."

It is evident from the above that the toreo of Belmonte, like the secret of any really great art, defies analysis. Above all technical consideration rises the personal equation, ever baffling and incomprehensible. So mysterious is the play of this young matador and so swift and furious his death stroke that his countrymen liken his fighting to a sudden storm. It is even reported that Guerrito, himself so famous as a bull-fighter, was amazed at the dangers run by the young matador, and said, "Let him who would see Belmonte see him soon!"

It is hardly necessary to say that Belmonte is a rich man. When one is paid at the rate of eight hundred dollars a bull, and kills three bulls a day, sometimes twice a week, the question of poverty is not a serious one. "High pay," one might say, when university professors make less, in a year, than Belmonte makes in a day. But there is a reverse side to the medal. This extraordinary matador has escaped death—narrowly and by the merest margin—over three thousand times. There is no end to the number of his wounds and bruises. One leg aione has been pierced a dozen times. The horn of a bull has even perforated his under jaw, entering from below the chin and emerging through the mouth. He has been trampled, dragged, and tossed in air. So that the remuneration is not perhaps as high as it seems.

Senora Belmonte is now in New York, awaiting her husband's return from Peru.

For the rest, Belmonte is a modest, unaffected personality, loving family life, and devoted to the care of his beautiful country seat at Utrera near Seville. Here, far from the frenzied plaudits of the crowd, he breeds fighting bulls and other live stock as well as supervises extensive olive oil and wine interests. A major portion of the truly fantastic sums he gains in the arena lie puts back into the soil of his native Andalucia. Belmonte who is now in Peru, from whence lie will shortly bring back wellnigh as much gold as Pizarro wrung from the ancient Incas, is in fact simple in his tastes and conservative in his private life. Married to a beautiful Peruvian and the father of two adorable little girls, he can well afford to look leisurely back upon a vivid, picturesque career. He can recall the time when as a mere stripling he used to swim the arm of Guadalquivir south of Seville, and fight bulls single handed on the moonlit marshes. He also remembers with affectionate gratitude the fact that his friend Zuloaga presented him with his first bull-fighter's cape when he was actually too poor to buy one himself.

So much for the past and present, yet what does the future hold for this steel-souled matador? Will he reenter the ring when he returns to Spain and one day meet his fateful toro—mayhap a descendent of the redoubtable Manada—or will he, like Guerrita, discreetly retire to his Andalusian farmstead with full pockets and undimmed fame? Does he in brief regard this earthly life of ours as a mere adventure or as an asylum—' Ouien sabe?

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now