Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowHow Modern Music Gets That Way

Some Notes on Stravinsky, Schoenberg, and Satie, as Representative Moderns

VIRGIL THOMSON

Editor's Note: The radical school of music has thrown auditors into as much confusion as the corresponding movements in literature and art. On the one hand are those who believe that modern music is nothing but futility, decadence, and bluff, and that the great days of Bach, Beethoven, and Brahms arc over forever. On the other hand, there are the ardent champions of the modernists who assert that the great classic composers were not recognized in their own day and that as soon as we accustom our ears to the discords, the atonalitics. and the intricate rhythms of modern music, we shall find it a vital, significant, and sophisticated expression of contemporary life and emotion. The truth seems to be that modern music does not involve a violent break with all musical tradition; and that, like the music of other days, it is good, bad, and indifferent

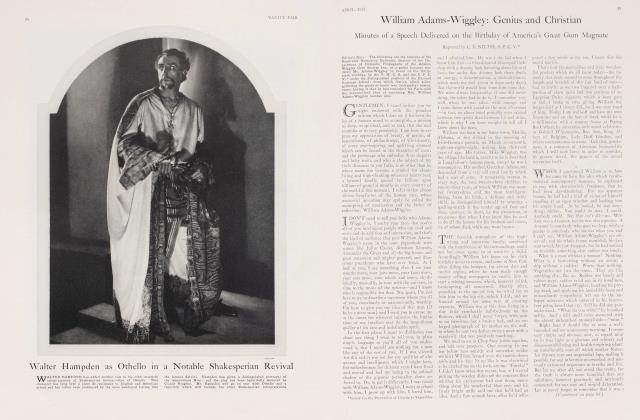

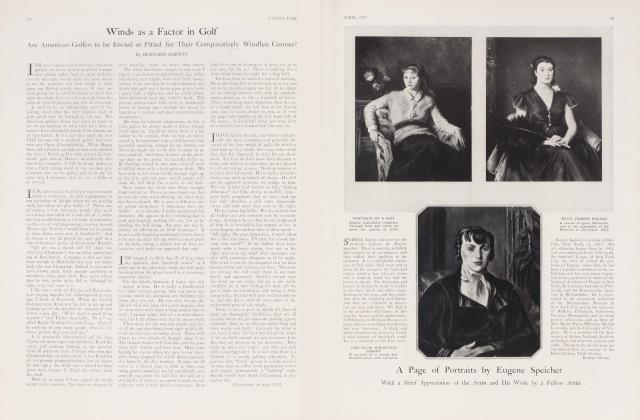

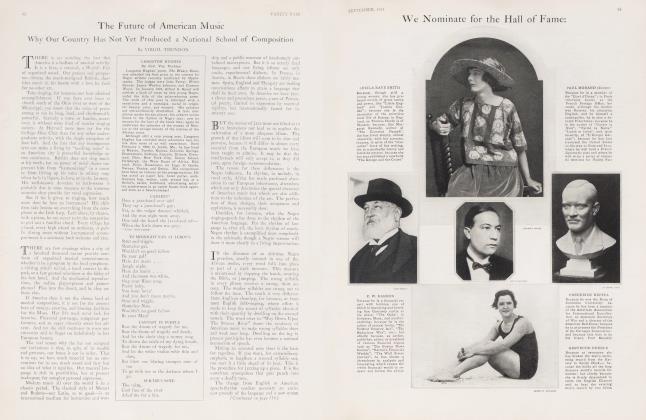

IGOR STRAVINSKY

Stravinsky has been, perhaps, the centre of the controversy about modern music. A composer of undoubted genius, he has introduced into music an objective and passionless quality that many musicians have claimed is foreign to the very essence of music. Although still a young man, Stravinsky has lived to find himself acclaimed by his one-time detractors. And it may also be said that his champions have recognized their own early enthusiasm as sometimes a thought too extravagant. In Stravinsky's recent tour of America as composer, pianist, and conductor, he completely won his audiences by his evident sincerity, his simplicity, and by something original and forceful in his personality. These qualities emerge, on a nearer view, as the fictitious Russian glamour fades

if II '"⅝ HE cultivated layman has always complained that music is not what it used to be. And he is perfectly right. Itneverwas.

Of the live "senses" of music—melody, rhythm, instrumentation, harmony, and form —perhaps melody has changed the least, although the charge of being unmelodic is the one most frequently brought against a new style; and indeed the songs that Mine. Eva Gauthier sings arc not quite like the airs from Don Giovanni. Even the symphonic style of the eighteenth century was dominated melodically by the idea of the human voice.

OUR melodies arc bv comparison unsingable, although they are at least not complicated by trills and roulades. In rhythm, we tend to avoid the regular metre of classical music and to cultivate instead the carefully irregular phraseology of prose or vers libre. In this we are closer to the sixteenth century, when Palestrina and des Pres composed music to the cadences of church Latin, and when hvpnotic or infectious metres were reserved for the dance and the madrigal.

As for harmony and instrumentation, the eighteenth century always imagined a performance by stringed instruments,—which are so rich in discordant overtones that discords are not needed in the written notes. With our increasing preference for instruments of wind and percussion, a richer harmonv has become necessary because of the poverty of these instruments in natural or internal discord. Our taste in instrumentation has thus at the same time changed from the suave and silken sonoritv of blended fiddles to a highly precarious balance of contrasted timbres. Our scores are likely to call ior anything from a cuckoo-clock to a sewing machine.*

In musical form, or structure, we differ most of all, perhaps, from the classics. So varied and chaotic are the forms of today that it is unsafe to generalize. 'This might be hazarded, that we, today, have no interest in abstract proportion separated from feeling in music, and that we do not care for exact repetition or for very much filigree.

*An Imitation of the former is common enough, and the latter actually has a part written for it in Charpentier's opera, Louise.

Of the changing tastes in music generally, one might cite the fact that Haydn called Beethoven a dilletante and said that no piece that impudent young man could write would ever live. Schumann could not abide Wagner, and Gounod pronounced the symphony of Cesar Franck to be "incompetence carried to the length of dogmatism." Of the three major influences, the representative figures in modern music, Schoenberg, Stravinsky, and Satie, not one of them, probably, would have been intelligible to Brahms; and Brahms has been dead less than thirty years.

THE styles that these men represent may .iL be called the chief schools of living music, because although small national groups have written much that has charm and character, as in England, Italy and Spain, the technical means employed arc products of Russia and Germany and France. For a hundred years Russian composers have been experimenting with rhythms, especially prose, or non-harmonic harmony; that is, a harmony which pays no attention to "active" and "restful" intervals, to dissonances prepared and resolved. In the best work of this sort there is nothing one could properly call dissonance at all, because the chords have no "pull" to them; they do not determine the flow or structure of the music. Their function is rhythmic and coloristic; they arc designed to negate harmony, so that melodics may not be lost in mere sonority. Stravinsky's music, without doubt the most competent of this type, is an elaborate counterpoint of rhythms adorned with utterly simple little Russian tunes.

In Central Europe on the other hand, the problem of harmony, or the sequence of chords, has always been of first interest. Mozart's only important contribution to musical style was in this field. Researches in modulation stimulated the best of Schubert and Wagner and Brahms; indeed Tristan and Isolde is a monument, almost a treatise of chromatic harmony. Now the ultimate of chromaticism, of incessant modulation, is a completely flexible harmony which is never in any definite key at all. Such is the technique which Schoenberg has perfected and which is the model, conscious or unconscious, for most contemporary writing in Germany, Austria, and Hungary.

FRENCH music, in spite of its enormous in_1L fluencc, is a special taste. For five centuries it has been caviar to the rest of Europe. The Englishman, Dr. Burney, the greatest musical historian and critic of the eighteenth century, could find no music in it at all and considered as mere chauvinism the enthusiasm of audiences at the Paris opera. His view has been echoed in our day. "Frivolous," "monotonous," and "harsh" are still the favorite epithets of foreigners. In melody and rhythm French music is, in fact, rather plain, with a delicate monotony, like their landscape and their language. In instrumentation, or "color", it is unexpected and subtle, with a tendency always to contrast instruments, rather than blend them. A French orchestra, whether it plays loud or soft, has a curiously precise, almost brittle brilliance. Its sounds may lave you gently, but it never submerges you in a bath of warm violin vibrato.

So far French music is harmless enough, though anything so fragile, so witty, and so delicately poetic, is likely to be called trivial by the Germans. In rhythm and color it has long been a model to other nations, even its melodics have had occasionally some international success. Its crucial quality, however, is a certain way of handling harmony. The French do not use harmony for structure, as the Germans have done; or deny it, as the Russians arc doing. They simply play with it. They allow it to caress and adorn their music, but never to dominate. It was so employed by Rameau, by Berlioz, by Bizet, by Chabrier, even by C esar Franck.

(Continued on page 102)

(Continued from page 46)

Not till Debussy's time did the rest of the world discover this trick. Many have since imitated it with more 01 less skill, but the real taste for decorative harmony remains essentially French. Debussy or Ravel or Faure, all of them musicians of greater achievement than Satie, and greater masters of the harmonic style that is the essence of French music, might have been named as the leaders of this school, except that Debussy and Faure are dead, and Ravel has been offered the Legion of Honor. Satie is, in fact, of living French musicians the most delicate, frivolous (if you will), and precise. With true French economy he has reduced both notes and noise to an incredible minimum. He writes neither to inflame the listener nor to seduce him, but simply to clarify a text or an idea. It is especially appropriate that he should have chosen on one occasion to set to music some of Plato's Dialogues, because no other writer comes so near to the musical style recommended by the disciple of Socrates.

Contemporary music, then, borrows its methods mainly from these three sources, though the particular tune and accent of it may be local. Many composers experiment with a kind of harmony known as bitonalitv; that is, writing in two keys at once; and interesting moments of such music are to be found as far back as the Richard Strauss of the nineties. No systematic use of it, however, has yet appeared comparable in completeness to the atonality of Schoenberg or to the discordant but strictly tonal writing in which Stravinsky excels, although it is employed by nearly all composers for dramatic purposes and quite extensively by the French for sensuous musical ornament. In rhythm, the only style peculiar to our age which is not implied in Stravinsky is that of American jazz.

Of course, all this novelty and experiment are amazing, especially to orchestral subscribers whose musicalitv is bounded on the north by Beethoven and everywhere else by Paul Whiteman. "If composers want to say something new," they ask, "why can't they say it with the old language that we can understand?" Well, they can't for the same reason that Beethoven couldn't. Music is made of sounds, not ideas; and the only way to make new music is with new sounds. Much of this music is pretty poor stuff. Much of music always has been. But the people who make stupid modern pieces would certainly make just as stupid ones if they wrote in the style of Schumann. There is not a firstrate composer in history (not even Handel, even though he did spend half his time writing quite conventional Italian operas) who was not an inveterate searcher after novel methods. There is a satisfaction about wearing a brand new suit of clothes which one can never get from the best made-over in the world. Grandma Brahms's crinolines were superb; bv all means let us studv them and cherish their loveliness. But they are as useless nowadays for practical evening wear as Auntie Strauss's bustle.

Besides, it is not at all certain that composers really are trying to say something new. Perhaps it is only the language that is strange. We can't tell. For there is no way of knowing what Beethoven meant by the Fifth Symphony. We can't even find out what Schoenberg means by Pierrot Lunaire, although he is still alive and talking. Composers are never articulate about their pieces, and the opinions of sincere and learned critics are utterly contradictory. Take the case of Stravinsky, for instance. One writer loves the Sacre dn Printemps for its harshness, another finds that it caresses the ear. Some speak of its primitive brutality, others of its subtlety, or its rhythmic elaboration. The Chorale in L'histoire d'un Soldat has been admired as blasphemy; it has been called tender, reverent, and mvstical; also a bit of pure and meaningless counterpoint. The Pieces for Clarinet, which seem to you restrained and austere, someone else has thought hilarious. Who knows whether the composer meant Renard to be gay or bitter: Some say Petrouchka is passionate and Russian; some call it objective musical realism; Boris de Schloezer says it is not primarily either patriotic or pictorial and that if you forget the ballet and the programme notes you will find it to follow an ancient and purely West-European model, the classical sonata. Stravinsky is, for persons who prefer those qualities, discordant, rude, barbaric, violent; and for those of other predilections, sonorous, subtle, sophisticated, and cerebral. He has been regarded by half his admirers as a chaotic demiurge and by the other half as a scientist who operates upon the brain with surgical precision.

All this doesn't help much in the concert hall. The only thing we can do there, be the programme ancient or modern, is to listen. And curiously enough, if we listen naively, music soon begins to make sense. It doesn't make intellectual sense, because no music does. But it makes musical sense; that is, as soon as we get used to the sound of it, it ceases to annoy; and then either it bores us, or it becomes pleasant and exciting, and we have that feeling of stimulation which is our only real evidence that a piece is for us a good piece. It is indeed fortunate that our ear can adapt itself so readily as it does, because we shall not always have the nineteenth century with us. In Chicago and Boston, strange new names are seen where Chaikovski and Bruckner once were printed. The Stravinsky vogue has even reached New York. Ladies at the Philharmonic who two years ago stalked away in anger from the trumpets of Petrouchka today applauded that work to their last glove.

I he truth is that it is harder to "stay put" musically than it is to move along. It is pretty difficult to be an ancient in the modern world. But all that is necessary to be a modern is simply to live in the world and to go out a little.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now