Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe Cult of Jazz

VIRGIL THOMSON

THE worship of jazz is just another form of highbrowism, like the worship of discord or the worship of Brahms. To call Jazz "the folk-music of America" may be good advertising, but it is not very good criticism.

Jazz is too sophisticated to be folk-music. Like the Viennese waltz, it is self-conscious, formal, and urbane. Without losing for a moment its quality or its poise, it can indulge in negro wailing and Spanish heel-stamping; it can hint at oriental melodics and obscene backcountry dances, quote from the classic masters, and scream out the rhythms of a Methodist revival. It can behave so, because its quality depends upon one trick only, a certain 'way of sounding two rhythms at once in order to provoke a muscular response. In short, it is dancemusic and always will be dance music. Diverting pieces can be made out of it for the concert hall, pieces like Chabrier's Espaha and Liszt's Hungarian Rhapsodies, but there is almost no implication in it of any intrinsic musical quality beyond this elementary musclejerking. To imagine that a vigorous national art could grow in such meager soil is to fancy that real roses (or turnips either, for that matter) could be matured in the jardinieres of a ball room.

OUR local wild flowers, on the other hand, have long been used as material for American compositions, many of which have flavor, if not consistency. Edward MacDowell liked Indian themes and wrote a couple of semi-Wagnerian orchestral suites about them that were a sensation in the nineties. In fact, they are still played occasionally. Dvorak's New World Symphony is ever popular. It scarcely counts as new world music, however, because, in spite of Negro and Indian melodics, it manages to sound exactly like his four Bohemian symphonies. John Powell has pleased audiences with his excellent Negro Rhapsody, and Henry Gilbert has devoted a life time to the composition of suites and overtures that depict the gayeties of half-caste society in Louisiana. In the way of Negro music, the most authentic writing that I know of has been done by R. Nathaniel Delt, himself a negro and a cultivated musician. Most concert-goers and pianists know at least his Juba Dance. Probably the best negro music will always come from the negroes themselves. Mr. Powell writes about them as a Southern gentleman might retell their stories, sympathetically, perhaps, but more in delighted amusement than with any passion or faith.

Here exactly is the trouble with writing folk-fantasias. Unless the material is of one's own intimate folk-stuff, the music made from it is exterior, hard, and sentimental. And here also is the reason why jazz has been called a Pierian spring. It belongs to our experience as the Negro dances and the Kentucky mountain tunes never did. It is our native gin, so to speak. One feels as if one might almost achieve selfexpression on it.

This is probably an illusion. The principal large works it has inspired have been a ballet, Krazy Kat, and a Concertino for piano and orchestra, by John Aldcn Carpenter of Chicago; a Rhapsody in Blue by George Gershwin, of New York; and a Scherzo for two pianos and orchestra by Edward Burlingame Hill, Boston.

Of Mr. Carpenter's two pieces, the Concertino is by far the more successful, because it does not limit its Americanism to jazz and because it does not try so hard. Krazy Kat failed because the composer bet on a horse he didn't know anything about. The famous Catnip Blues in it are got together by pinning little furbelows of rag-time on to a long-winded melody that might just as well have come out of Deems Taylor's pantomime or Tristan and Isolde. Mr. Carpenter makes music out of measures and phrases rather than out of those short percussive sounds which are the rhythmic units of jazz.

Mr. Gershwin's piece, in spite of the excessive praise it has received, and in spite of its enormous superiority to anything that the better educated musicians have done in that style, (for Gershwin can write blues, if he can't rhapsodies), remains just some scraps of bully jazz sewed together with oratory and cadenzas out of Liszt. Mr. Gershwin is an excellent composer for the theatre. The concert room seems to clog rather than facilitate his expression. The Rhapsody is at best a piece of aesthetic snobbery. That, and no more, is its raison d'etre.

MR. HILL'S Scherzo comes as near jazz as John Powell's Negro Rhapsody docs to a camp-meeting of the African Methodist Episcopal Church. It is music about jazz, elegant Bostonian music, a witty and indecorous comment without any personal commitment. Mr. Carpenter, in exuberant Chicago style, embraces the popular muse as he might his neighbor's wife, dancing at the country club. Mr. Gershwin, though privately aware of her true character, would put her in an imported corset, give her a feather fan, and take her to Carnegie Hall. Mr. Hill knows only too well that as a New Englander and an academician he would find distasteful any extreme familiarity with one whose race and upbringing arc so different from his own.

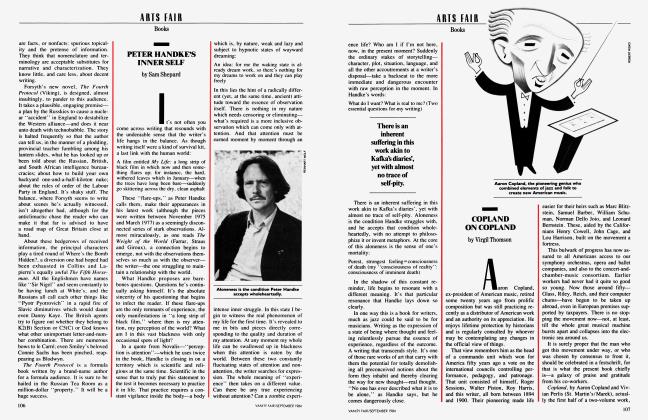

These pieces, the types for most of our highbrow jazz, are really charming works. They arc also disappointing, because they are touched with insincerity. I would trade them every one for the symphony of Aaron Copland. Mr. Copland's piece is less competently written. His instrumental technique is childish beside Hill's Parisian mastery. He has neither the mature architectural skill of Carpenter nor the melodic gift of Gershwin. And he makes no attempt to write jazz. He does build his themes by grouping notes together into measures and not by breaking measures up into notes. But this procedure, although essential to jazz, is in no way the essence of it. That essence is rather a muscle-jerking quality due to its counterpoint of regular against irregular beats. Copland accepts short-unit rhythm as a musical device without any patriotic or literary reference. There is not a Negro tune or a Broadway formula in his work. Its European affiliations, principally Stravinsky and Faure, are easily evident. And yet it seems everywhere to belong to us and to be our own. It is American music because it is honest, personal music written by an American young man.

TO BE an American one need not be ignorant. Perhaps one must be somewhat European, through reading, travel, or racial proximity. Europe is the cultural background, the point de vue from which we discover ourselves. To fear it is to worship it blindly. To accept it is to enrich one's life. And really there is so little danger of deracination. It may be true, as T. S. Eliot says, that it is the good fortune of Americans to become what no Frenchman or German or Italian ever becomes, a good European. It is certainly true that no American ever becomes what the European is already; that is, French, German, or Italian. If you doubt this, just look at your friends who have tried it.

The fear of foreign influence is, for this reason, simply another kind of provincialism. Of course we do bad work when we try consciously to imitate the aesthetic fashions of London or Paris. But we do just as bad work when we try to imitate the aesthetic fashions of New York and Chicago. The artist, to do good work, must accept without shame whatever influence may attract him; but he must also accept himself.

For, after all, America is just a collection of individuals, and amazingly different ones at that. The idea that they can be expressed by a standardized national art is of a piece with the idea that they should be cross-bred into a standardized national character, 100 per cent North American blond.

(Continued on page 118)

(Continued from page 54)

Fortunately, our musical vitality is too great to be much oppressed by standards. You have only to walk down a side street in any suburb at 8 P. M. to know that America is seething with a vast and explosive musical energy. There has probably been nothing like it since the German Reformation. Jazz itself, amazing as it is, is only the temporary urban aspect of that energy. It is, of course, a power in our lives. Even if it had not been advertised by critics, we could hardly escape its rhythmic presence. There is no danger we shall forget it. The danger is rather that its cult may intimidate those private devotions, local or foreign, which lie close to the heart of the individual composer and which must ever furnish the true passion of his music.

For where the heart lies, there lies the only honest art. Mademoiselle Nadia Boulanger says "You have all the same difficulty, you Americans. You have enormously of talent, but you lack the courage to be yourselves."

I wonder if we haven't learned the wrong lesson from the success of jazz. It doesn't prove that nothing else is worth doing. It only proves that if you keep on doing your own stuff, in spite of the highbrows, you will eventually get to be good at it. And what we really like about jazz is not so much that it is American (because it isn't, very much) as that, whatever it is, it's darned good. All our aesthetic philosophy, in fact, born of our eclectic breeding, is just that. We admire whatever is good of its kind, complete, self-assured and unafraid.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now