Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe Future of American Music

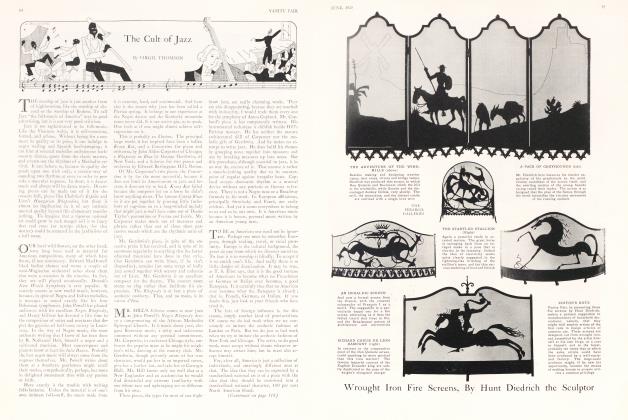

Why Our Country Has Not Yet Produced a National School of Composition

VIRGIL THOMSON

THERE is no avoiding the fact that America is a bedlam of musical activity. It is a hive, a carnival, a World's Fair of organized sound. Our patient and prosperous citizen, the much-maligned Babbitt, cherishes music in his bosom with a love he feels for no other art.

Take singing, for instance, our least admired accomplishment. If you have ever been to church south of the Ohio river or west of the Mississippi, you know that the voice of praise among us can be long, loud, and rhythmically powerful. Scarcely a town or hamlet, moreover, is without some kind of secular singing society. At Harvard more men try for the College Glee Club than for any other undergraduate activity, with the single exception of foot ball. And the fact that any incompetent tyro can make a living by "teaching voice" in an American city is proverbial knowledge on two continents. Babbitt docs not sing much at his work; but no power of social shame can prevent him from "harmonizing" in a canoe or from lifting up his voice in solitary song when he is in liquor, in love, or in the lavatory. His well-known devotion to bath-rooms is probably due in some measure to the sonorous acoustics they provide for vocal expression.

But if he is given to singing, how much more does he love an instrument! His children take lessons on everything from the saxophone to the Irish harp. Left alone, by chance, with a piano, he can never resist the temptation to pick out a familiar chord. Every village has a band, every high school an orchestra. A public dining room without instrumental accompaniment is a sanctuary both welcome and rare.

THERE are few evenings when a city of a hundred thousand cannot provide some form of organized musical entertainment, whether it be a program by the local symphony, a visiting artist's recital, a band concert in the park, or a few genteel selections in the lobby of the best hotel. And the mechanical reproductions, the radios, player-pianos and gramophones! Flee into the desert, and lo, they are there also.

If America then is not the chosen land of musical composition, it is not for the absence here of money, exercise, and housing facilities for the Muse. Her life need never lack for luxuries. Financial patronage, competent performers, and an eager clientele await her advent. And yet she still continues to scorn our entreaties and to linger on indefinitely in her European haunts.

The real reason why she lias not accepted our invitations is that, in spite of its wealth and pretense, our house is not in order. That is to say, we have much material but no conventions for its use, much sound and fury but no idea of what it signifies. Our musical language is rich in possibilities, but at present inadequate for complex personal expression.

Modern music all over the world is in a chaotic period. The classical style of Mozart and Brahms—our Latin, so to speak—is an international medium for instruction and worship and a public museum of handsomely embalmed masterpieces. But it is an utterly dead language; and our living idioms arc only crude, experimental dialects. In France, in Austria, in Russia these dialects arc fairly mature. Spain, England and Hungary are making conscientious efforts to attain a language that shall be their own. In America we have jazz, a clever and precocious patois, a sort of Provencal poetry, limited in expression by metrical rigidity, but internationally famed for its amatory uses.

BUT the success of jazz must not blind us to its limitations nor lead us to neglect the cultivation of a more adequate idiom. 7'he growth of that idiom will seem to be slow and perverse, because it will differ in almost everv essential from the European music We hate been taught to admire. It may be that the intellectuals will only accept it, as they did jazz, upon foreign recommendation.

The reason for these differences is the Negro influence. In rhythm, in inclodv, in vocal style, Africa has made profound alterations in our European inheritance, alterations which not only determine the special character of American music but which are also additions to the technique of the art. The perfection of these changes, their acceptance and application, is necessarily slow.

Consider, for instance, what the Negro singing-speech has done to the rhythm of the American language. For the rhythm of language is, after all, the basic rhythm of music. Negro rhythm is exemplified most completely in the spirituals, though a Negro sermon will show it more clearly in a living improvisation.

IN the discourse of an old-time Negro preacher, usually intoned in one of the African modes, every word falls into place as part of a rigid measure. This measure is maintained by clapping the hands, swatting the Bible, or jumping. The strong syllable in every phrase receives a strong, short accent. The weaker syllables arc strung out to follow the tunc. The result is very different from Anglican chanting, for instance, or from most English folk-singing, where effort is made to keep the accent of syllables identical with their quantity by dwelling on the stressed vowels. The word river in "Way Down Upon The Swanee River" shows the tendency of American music to make strong syllables short and weak ones long. Dwelling on the ing in present participles has even become a national mannerism of speech.

Making an accented note short is the basis for rag-time. If you want, for extraordinary emphasis, to lengthen a stressed syllable out, you start it a little ahead of its beat. This is the procedure for jazzing up a piece. It is the unwritten syncopation that puts punch into many a deadly tunc.

The change from English to American speech-rhythm renders necessary an entire new prosody of the language and a new system of vocalization it gives a new rhythmic style to instrumental music which, in turn, makes necessary many changes in harmonic conventions and a completely new instrumental usage. We have scarcely begun to chart these changes or to assist them. Our fertile wilderness will yield neither champagne nor hot house grapes until we submit it to a good deal of careful cultivation, and probably then it will insist upon growing some entirely unexpected product like alfalfa. In any case its fruition is as much a matter of time as of effort.

(Continued on page 116)

(Continued from page 62)

Of course, self-respect demands that we really try to do something. Our composers are industrious and erudite. Those who write symphonies are forced, consequently, to write in some European style congenial to that form, or to ape the classic manner, introducing such occasional bits of American phraseology as will lend local color without obscuring the outline of the work. Even that is difficult to do well, because no American has ever managed to feel at home in the longer Continental forms—the ballet, the opera, the sonata, the fugue—let alone make a significant contribution to their progress. We have learned their rhyme, but we cannot sense their reason. The rhythm of our minds, our way of thought and feeling, is profoundly different from that of European minds. When we realize the nature of that difference, we shall, of course, be articulate. All we know at present is that, not being a European people, we cannot write European music, any more than we can write French poetry.

If America never produces anything but jazz, she will have at least two entries to her credit in the accountingItook of culture, one of the thing itself and another of its influence upon European composers—Debussy, Satie, Milhaud, Stravinsky. But it is hardly credible that her enormous enthusiasm should not shape itself eventually into a language and a literature commensurate with the abundance of her material ami the sincerity of her devotion to it.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now